1.

Keith Richards ended up calling his memoir Life, not, as had been planned, My Life, the more conventional choice. Almost any memoir ever written could be called My Life. It’s what Bill Clinton called his own memoir. For Clinton it was a defensive, even a defiant, title, but then, memoirs are defensive by nature. To exist, they must justify their existence. Uniqueness—the “my” in “my life”—is an important condition: without it none but the first-ever memoir would have to exist. And the suspicion of insufficient uniqueness is one great nullifier of memoir: this is the problem when memoir subgenres (abuse memoirs, addiction memoirs, conversion memoirs, travel memoirs) promise to convey shock or pathos or virtue, but get their ingredients from a cake mix.

The recent crop of purloined, plagiarized, and manufactured memoirs—James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces, for example—unsettled readers not because some sacred line dividing fact and fiction had been crossed, but instead, I think, because they suggested we might actually be running out of interesting lives. Aspiring memoirists may just have to start writing fiction: though there the competition to make something new and good is, if anything, even more keen.

The temptation for most memoirists is to beef up, at times even to make up, life; for Richards, who has lived one of the most eventful and excessive lives ever, the point is to tamp it down. His is an odd book for many reasons, among them its refusal to impute any meaning to the structure of experience, beyond its basic contingency. The book tells no “story,” presents no overwrought “themes,” proposes no shape to life beyond the amorphous ooze of passing time. Thus the hilariously nonchalant title, which, shorn of the expected first-person possessive, would suggest that Richards’s life is more or less the one we all experience.

At one time or another, everyone rides in a red Cadillac with the Ronettes out to Jones Beach, then wakes up on Ronnie Spector’s mother’s living room floor in Spanish Harlem, to a plate of bacon and eggs. We’ve all had the major licks of “Satisfaction” come to us in a dream, then adjourned to the pool to write the lyrics with Mick Jagger. This is the kind of thing that happens. Uschi Obermaier, the German leftist supermodel, chews off your earring in a Japanese-style hotel in Rotterdam, leaving you with a “permanent malformation” on your right earlobe. The prime minister of Canada’s wife turns up in your hotel room, looking eager to party. That’s life. Or, Life.

The surfeit of wildly nontransferable details (the earlobe-gnawing supermodel/communard, the varieties of smack, scrapes, fame, hotel rooms, speedboats, and Bentleys) is nearly comic, in a book whose title professes grounds to generalize, if not to moralize. Richards’s near-total abandoning of moral counsel for forms of practical guidance—not to not do heroin for decades, but how to do it so as not to die—makes Life feel at times like an instructional pamphlet or how-to guide. Moral counsel is one of the classic rationales for memoir, from Augustine forward (though many memoirs, especially if they are by businessmen or athletes, do give pointers: know the markets, know the strike zone). There is almost no moralizing here, and even the practical instruction, since it pertains to a life only Keith Richards could have lived, is often strictly useless (though the recipe for bangers and mash Richards gives at the book’s conclusion looks tasty). What am I going to do with information about Swiss detox clinics, open-tuning a Gibson, or villa-hunting on the Côte d’Azur?

Life is, despite itself, a raffish and unlikely heir to two great memoirs of thrift and common sense, Walden and Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. Like them, it provides the unaccountable pleasure of being told precisely how to do things you will never want or need to do. This displacement of moral instruction onto purely practical, if flagrantly useless, direction itself implies a moral position. Richards elevates expertise, street smarts, tactical rather than strategic intelligence, industry, and adaptability over all forms of metaphysical cant, a code he developed in childhood that found its great adversary only much later in life, in the fame-obsessed and dandyish Mick Jagger. These are the Thoreauvian virtues, and Life is at times a kind of peregrine Walden.

Thoreau tells us how we can hew timbers six inches square, or sound the depths of the pond, or tight-shingle a homemade dwelling, or dig a cellar hole. But what he is really telling us is that we should know how to do such things, or at least know that knowing how to do them, or things like them, is an important use of mind. Substitute Richards’s canon of skills (if you need to master your tapes for nine sleepless days straight, try Merck cocaine) for Thoreau’s, and you get Life, the title of which even starts to sound like a suppressed chapter title from Walden. Of course “life” carries another sense: it is the opposite of “death,” though in Richards’s case the two sit side by side almost interchangeably, like salt and pepper.

Advertisement

Richards’s death-in-life and life-in-death persona—the skull ring, the cadaverous thinness, the rumors that he once snorted his father’s cremated remains—only seems like an act because he didn’t, in fact, die. Odds were placed and bets were made, but Keith defied the death pools. He seems almost apologetic, abashed, about having stayed alive, as though he might be willing to reimburse the people who bet against it. There are dozens of deaths in Life, most tragically the crib death, in 1975, of Richards’s two-month-old son, Tara. The child, he says, still “invades” him: “He bangs into me once a week or so. I have a boy missing.” That death and the death of Richards’s chum the country music pioneer Gram Parsons, a few years before, along with the astonishing ferment in the Stones’ music that ended (with Exile on Main Street) in 1972 give the second half of this book a posthumous air. The pragmatic, instruction-giving Richards cannot reach across time and tell Gram Parsons not to get so high when he gets high, or be there when his wife, Anita Pallenberg, finds their child dead. This helplessness following upon heedlessness, a zone of feeling no aplomb or expertise can manage, is the great tragic tone that counterbalances Richards’s nonchalance.

2.

Memoir, as a genre that still prizes authenticity over artifice, puts a special pressure on literary style: anything too lyrical or shimmering invalidates the memoirist’s moral claim. The best tone for the job is still Henry Adams’s self-savagery, which allows the reader to restore mentally whatever sympathy for Adams Adams withholds from himself. Richards’s sharpness is surprising coming from a guy whose mind, everyone had to assume, was by now a salvage heap. On stage, he is a prince of apparent mindlessness, deploying a small repertoire of lip curls, grimaces, and crooked smiles. You expect that his memoir would be written in the language-equivalent of those facial expressions, but Richards is and always has been a writer, one of the greatest songwriters in rock history.

Richards has said that he considers his job “to write songs for Mick Jagger to sing,” though in practice, this has usually meant that the shape of the song is devised by Richards, while most of the “hard work of filling it in and making it interesting” falls to Jagger (only “Brown Sugar,” of their well-known songs, was 100 percent Jagger; the rest they assembled together).

Much of that work happens in performance; for Jagger, lyrics are malleable within performance. The songs are almost all dead on the page. Furthermore, Stones production (there are rare exceptions) normally sinks the vocals into the instrumentation, and Jagger’s drawl is sometimes completely unintelligible. Often the chorus (for example, “Brown Sugar, how come you taste so good” or “Jumpin’ Jack Flash, it’s a gas, gas gas”) will emerge and shine, clear as day, after an interval of murky verbal gestures that only sometimes approximate clear words. It’s not “writing” in the folk-based, lyrics-based tradition of Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell: nothing is ever lyrically devastating in a Stones song. Richards writes grooves, with words attached.

He is, however, also a marvelous sentence-maker, though every sentence seems cut short by the eruption (to the reader, inaudible) of phlegm from his lungs and the consequent coughing fit. This kind of spasm punctuates all of Richards’s spoken statements; you can hear it in any interview, and, in a book that feels entirely dictated, it also happens on the page. The vocabulary is in a race with the phlegm. Here is a typical passage concerning the “Prince” Stanislas Klossowski de Rola, known as “The Dandy Aesthete of Swinging London,” son of the painter Balthus, who is dispatched to Rome by the band member Brian Jones to bring back Anita Pallenberg, Jones’s girlfriend, whom Richards has stolen. The prince was called “Stash”:

Stash had the bullshit credentials of the period—the patter of mysticism, the lofty talk of alchemy and the secret arts, all basically employed in the service of leg-over. How gullible were the ladies. He was a roué and a playboy, liked to look upon himself as Casanova. What an amazing creature to sweep through the twentieth century.

“Stash” is in fact a lifelong “student of the Alchemical arts,” now living in his father’s castle in Lazio. He is just one of many mystics and sages who drift into Richards’s sights only to get blasted to smithereens (Allen Ginsberg, whom Richards describes unforgettably as an “old gasbag,” omming and “pontificating” at Jagger’s place in London, is another). In interviews, Richards’s very funny remarks also crack him up (and start him coughing) not because he loves the sound of his own voice, but because he has captured the absurdity of these cats so vividly that in describing it he suffers it afresh.

Advertisement

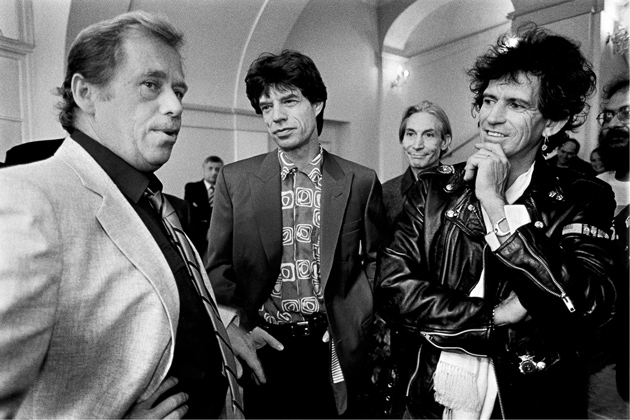

As the entourage of aristocrat-magi bearing opium, movie stars, painters, and groupies (Margaret Trudeau among them) assembles, all of them blathering about mysticism, mishandling the drugs, lazing about in bathrobes, Richards himself comes to seem like a transparent, albeit bloodshot, eyeball: the zonked, nonparticipant nucleus of the whole Stones organism. His passivity catalyzes wild behavior in others; he is shaping social space by staring at his guitar. Marlon Brando tries to get him into a ménage à trois with Anita Pallenberg. “Later, pal” is Richards’s response, but the real response is this memoir, with all the real-time suppressed judgments going off like little time bombs.

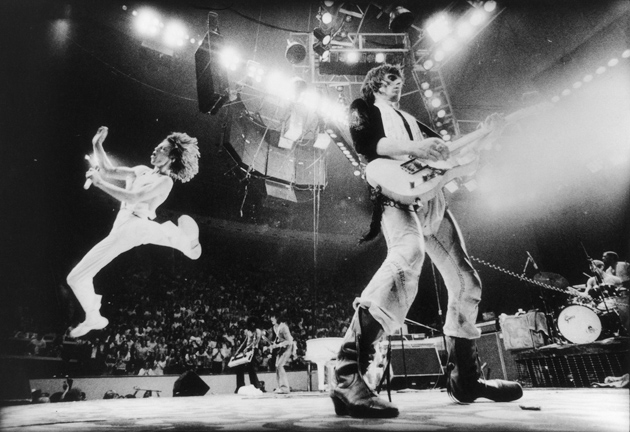

His general air of disengagement was maintained in mid-career by heroin addiction. This was the mounting physical cost he incurred as his celebrity snowballed. But his disengagement, sometimes fortified by strong drugs, was in part a way of staking out permanently the authorial point of view, a decision to remain the beholder rather than (like Jagger) the beheld. You can see it in his stage manner. He and Jagger do their occasional and brief pas de deux at the front of the stage, but usually Keith is just back there, making his guitar make sounds, the byproduct of which is music, the byproduct of music being a band, and fame, and money, and girls, and cars, and self-destruction, and all the rest of it. He is a great ironist, in ways he doesn’t even fully intend: with Richards’s own feet planted on the ground, Jagger’s paroxysms and fits seem all the more bizarre (bizarrely beautiful, but still bizarre: Richards opines that Mick got his tight, jackhammering moves from playing their first gigs on very small stages, with lots of equipment limiting his range). He ironizes the band, the scene, the spectacle, and most importantly and radically his own body, regarding it and its ravages with resignation, even amusement. Every junkie has this relationship to his body; nobody takes his body on that kind of ride without thinking of it as rather pitifully a thing apart.

Richards’s childhood in the dreary town of Dartford, east of London, along the Thames, gave him a sense of existence itself—“life”—as something randomly meted out to begin with, and brutal for the lucky few who make it. Dartford had been known since the Roman times for thievery: “Sutton for mutton, Kirkby for beef, South Darne for gingerbread, Dartford for a thief” went the old laud. Little Keith was routinely bullied and robbed, though he had “that thing little fuckers have, which is called speed.” His backyard was the Dartford Marshes, where “everything unwanted by anyone else had been dumped” for a hundred years: “isolation and smallpox hospitals, leper colonies, gunpowder factories, lunatic asylums.” The asylums corralled Dartford in a ring (“You’d give people directions: ‘Go past the loony bin, not the big one, the small one'”) and every so often an air-raid siren repurposed as an escape alarm would sound: another “loony” (after “flitting through the shrubbery”) would be found “in his little nightshirt, shivering on Dartford Heath.”

Mick Jagger makes his first appearance in this book as a thirteen-year-old boy with a summer job at the “Bexley nuthouse, the Maypole,” a “bit more upper-class” asylum (Richards thinks everything about Jagger is too posh), doing “the catering, taking round their lunches.” Jagger was growing up in the fractionally less grim neighborhood nearby; Keith sees him around town, selling ice cream in front of Dartford town hall, and in the fullness of time they bond over records:

Did we hit it off? You get in a carriage with a guy that’s got Rockin’ at the Hops by Chuck Berry on Chess Records, and The Best of Muddy Waters also under his arm, you are gonna hit it off. It’s the real shit. I had no idea how to get hold of that.

Mick “had the London thing down,” had contacts, a catalog from Chess records, and, for a pen pal, Marshall Chess, Mr. Chess’s son who worked in the mailroom and would later become president of Rolling Stones Records. Mick had seen Buddy Holly play, and played the Buddy Holly songs he heard—if he didn’t play them, he wouldn’t hear them—in bars around Dartford.

Anyone reading this review can go to YouTube now and experience Muddy Waters, or Chuck Berry, or Buddy Holly, or the first Stones recordings, or anything else they want to see, instantly: ads for Freshen-up gum from the Eighties; a spot George Plimpton did for Intellivision, an early video game. Anything. I am not making an original point, but it cannot be reiterated enough: the experience of making and taking in culture is now, for the first time in human history, a condition of almost paralyzing overabundance. For millennia it was a condition of scarcity; and all the ways we regard things we want but cannot have, in those faraway days, stood between people and the art or music they needed to have: yearning, craving, imagining the absent object so fully that when the real thing appears in your hands, it almost doesn’t match up. Nobody will ever again experience what Keith Richards and Mick Jagger experienced in Dartford, scrounging for blues records. The Rolling Stones do not happen in any other context: they were a band based on craving, impersonation, tribute: white guys from England who worshiped black blues and later, to a lesser extent, country, reggae, disco, and rap.

When the situation changed in part because the Stones changed it, and suddenly you could hear (and even meet and play with) Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley, the band lost its way. They depended, for their force, on a body-memory of those early cravings for music they knew only by rumor and innuendo. Other cravings, for drugs and fame, were not sufficient, and had much more dire downsides. The early Stones were in a constant huddle, dissecting blues songs in front of the speakers and playing them back for each other and then for their few fans. They thought of themselves, not even as a band, really, but as a way of distributing music the radio never played.

With the first flush of fame, the huddle became a defensive crouch, which still kept them together, though the risk of being strangled by teenage girls was real. Nothing in their later career, not even Altamont, the free concert where everything went awry, ever reached the level of chaos of those early shows, where most of the day would be spent “planning the in and the out” rather than the gig itself (the audiences were so loud that the band could play anything, and once, to prove that they were inaudible, played “Popeye the Sailor Man” to the frenzied mob).

In the great film about their 1969 tour, Albert and David Maysles’ Gimme Shelter, there is a scene of the band listening to a tape of “Wild Horses,” the gorgeous ballad by Richards and Jagger from the album Sticky Fingers, at Muscle Shoals Studio in Alabama. The next day they would fly to Altamont. Charlie Watts listens for his drums; he seems to like what he hears. Jagger is silent, then suddenly businesslike, then, tying an imaginary bow as the song concludes, happy. Various managers and hands look rhapsodic.

The image of Richards, though, is what stays with you: head back, eyes closed, sloppily lip-synching to Jagger’s vocals. Keith had written the song as a lullaby for Marlon, his son, according to Jim Dickinson. Jagger got his hands on it and made it a love song, probably addressed to Marianne Faithful. It is hard to know whether Keith is synching his own lyrics, which Jagger changed, or is simply too high to sing along. But it is an unforgettable image, the image of a band beholding its own complex chemistry, even as they are beheld by the Maysles’ camera. That moment seems to me the peak of the Stones’ career. From there, as Richards puts it, things went “from the sublime to the ridiculous.”

3.

Richards adds mainly footnotes to our understanding of Altamont and the ensuing years, when the Stones would make their greatest record, Exile on Main Street, at Nellcoˆte, the villa he rented on the Riviera. There is a huge trove of images and stories from this period that his own memories cannot but have drawn on; he seems to remember, from Altamont, mainly those images that Gimme Shelter captured. And yet those years, between 1968 and 1972 and the release of Exile, are the critical years for thinking about the meaning of the Rolling Stones.

There were several elements that crested at Altamont on December 6, 1969, all of them putting special pressure on the band as it ran through the opening chords of its first number, “Sympathy for the Devil.” That song was a case in point. The Stones were in the studio recording it when Robert Kennedy was murdered in June 1968; their response was to make the lyric “I shouted out who killed Kennedy” plural: simple as that, that was easy. Jean-Luc Godard had filmed the band recording the song, and released his film named for it, in November 1968. You could argue that for a song that both reflected and fed the cultural frenzy of the moment, “Sympathy for the Devil” was unprecedented: it is still chilling to hear those lines, “I shouted out who killed the Kennedys/When after all, it was you and me.”

The first pressure was the American situation at large, brought to a boil in part by the Stones’ music, but so much more lurid and dangerous than anything the Stones could have imagined when they began their 1969 tour. “The end of the dream as far as I was concerned,” Richards writes; but then “America was so extreme, veering between Quaker and the next minute free love, and it is still like that.” When the madness breaks out at Altamont, Jagger at first seems almost gratified: “Something very funny always happens when we start that number,” he chuckles, and then starts it over again. He digs deep for the flower-child crowd-control vocabulary: “Brothers…Sisters…. If we are all one, let’s act as if we are all one.” But the Stones were still speaking their darker, more tragic idiom siphoned from the Delta blues. They didn’t do flower power well; they never could.

The second pressure was race, and here the strands are very tangled. It was a black man who was killed at Altamont, the only black man in the big crowd gathered near the stage, and one of the few black people we see in the entire film (in a comic moment, a white woman who looks like she was sent from the Pacific Heights Junior League is seen handing out “Free the Panthers” broadsides to a baffled-looking black guy). His name was Meredith Hunter, an eighteen-year-old boy from Berkeley, and (as anyone who has seen the film remembers) he was wearing a resplendent lime-colored suit. Surprisingly little is known about him: a filmmaker named Sam Green has made a short documentary, lot 63, grave c, named for Hunter’s unmarked plot at the East Vallejo cemetery north of San Francisco.

The Stones had worshiped black blues since before they were a band: Jagger, who as a teenager had one of his many summer jobs as a kind of workout leader at the nearby American military base, befriended a black cook who played R&B for him. But their sense of race was, and still is, sanitized: all the black people they knew were Delta bluesmen or piano players in James Brown’s band. When they touch on race, as in “Brown Sugar,” they always get into trouble. That’s a great song, but a really bad idea.

What is so illuminating, but also so much a problem, about this band—you can hear it in Jagger’s singing, as he goes from honky-tonk to soul and back again in a single album—is its willingness to impersonate the blues in a purely musical context, almost as though there is no history outside the recording studio. People can debate whether the black man in the lime-green suit was killed because of his race (on the one hand, after scuffling with the Hells Angels who had been hired as security guards, he had pulled a gun, and was rushing the stage; on the other, he had been targeted by the Angels, who were notorious racists, perhaps because he came to the show with his blond girlfriend), but the tragic appearance of a single black figure in that sea of white one minute and the brutal stabbing just a minute later feel like a direct consequence of the music the Stones were making, so brilliantly, on stage.

And then there was fame, which the band was handling in its various ways: Jagger was making Performance, the avant-garde crime film with a bad-trip aesthetic, and injuring his hand shooting a revolver on the set of a film about the Australian outlaw Ned Kelly; Brian Jones, after being fired, died; the drummer Charlie Watts, the stone-faced stoic, was immersed in jazz, the way he always had been. Keith was getting high and writing music. The band was always on the lam: Richards learned to look out his window every morning to check for unmarked cars, the way you would do to check whether the paper had been delivered. The frenzy is captured in Life, but for me the best book about the period is still Stanley Booth’s True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (2000), which has the tricky virtue of having been written from the eye of the storm; anyone suspicious of the recollective sheen of memoir, or of Keith’s memory, should seek it out.

The double-sized album Exile on Main Street, which was remastered (to my mind, unsuccessfully) and reissued last year, to accompany a puff-piece documentary called Stones in Exile, is fame in photonegative: a sprawling collection with no real single (“Tumbling Dice,” nobody’s favorite Stones song, is its one radio hit), a number of forgettable songs, and the ambience of a humid basement. The band had fled English taxes for France; Richards had rented his villa, where the Gestapo had its French headquarters and, rumor has it, had left behind boxes of narcotics used in interrogations that had to be removed lest he start ingesting Nazi junk. Power for the instruments and equipment was hijacked from the nearby railway. Children rolled joints for their parents, and tucked them in snug in their beds after their epic nights awake.

Exile is traditionally understood to be “Keith’s record,” the album that depends the least on Jagger’s charisma, and that depends most upon—some would say suffers the most from—Keith’s sleepwalking brilliance as a musician. Remastered, it sounds too cleaned up. As everyone points out, only the rudiments of the record were completed in France; the tapes were brought to L.A. after that lost summer, and the band put the record together in the conventional way, sometimes loaning a song-in-progress to Wolfman Jack to play on his radio show, then taking a drive to hear how it sounded, before immediately confiscating the contraband song and smuggling it back into the studio.

But the record retains the Keith Richards virtues in their pure form, which makes it the musical twin of this splendid autobiography: sharpness, snarl, antisocial affability, immersion in music first, myth-making second, and above all (in prose, as on the guitar) a kind of virtuosity—a talent for life—that makes style beside the point.

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know