Sooner or later all who write about Ronald Reagan find themselves at grips with a puzzle. His son Ron (the name he uses as author of this memoir) is no exception. Though he has had a longer and more intimate relationship with Reagan than most people, at the age of fifty-two Ron is still trying to figure out what made his father, ostensibly such an ordinary fellow, one of the past century’s most successful political leaders.

His sensitive and arresting memoir about “Dad,” as he calls his father throughout, is especially good when exploring the human puzzle. During his father’s presidency, Republican reactionaries, unhappy when he moved toward political moderation, used to shout, “Let Reagan be Reagan!” but it was never clear who the Reagan was that they wanted Reagan to be.

His son suggests that Reagan was the self-invention of a boyish daydreamer stuck in the hard-knock life of a drab prairie town in Illinois. By using the arts of show business he managed to rise from the world of let’s pretend to the presidency, all the time remaining so unknowably private that he often seemed a stranger to his own children. Such, at any rate, is Ron’s analysis.

“He was easy to love but hard to know” is the one conclusion about which he seems certain. Reagan’s friends, relatives, associates, and biographers have been arriving at the same judgment for years. Even his wife Nancy, said to be the only person who really understood him, seemed defeated by his impenetrable privacy when she told his biographer Lou Cannon, “You can get just so far to Ronnie and then something happens.”

Unlike his mother, Ron is willing to explore the puzzle in a skeptical frame of mind, which produces a variety of material, all of it interesting for its inside view of a celebrated family that was anything but a middle-class dream of domestic bliss, and some of it decidedly unflattering. There is the problem of personal family relationships. Twice married, Reagan was father to four children (a fifth died at birth), who over the years have complained in one form or another that he was remote and inattentive, or, as Ron puts it, “you couldn’t help wondering sometimes whether he remembered you once you were out of his sight.”

His book is, nevertheless, warmly affectionate, which is not always the tone in which Southern California children dilate on deceased celebrity parents. (“It’s not even safe to die anymore,” Bob Hope observed after Bing Crosby’s son issued a postmortem book saying Bing had been a terrible father.) Ron seems genuinely fond of “Dad,” but fondness, as many a graying parent well knows, cannot stifle the child eager to favor the old man and even dear old Mom with youth’s cheeky critique. Which is sometimes even painfully sound.

In his genially affectionate way, Ron manages to convey the impression that his father was not only lacking in parental skills, but also cruel and unfair to his own father when portraying him as a far-gone alcoholic. “Strange” is Ron’s word for Reagan’s relationships with his children. “Not darkly strange, mind you.” To the contrary, he was “so naturally sunny,” guileless, and incapable of pettiness and cynicism that he represented “a whole new category of strangeness,” his son writes.

I could share an hour of warm camaraderie with Dad, then once I’d walked out the door, get the uncanny feeling I’d disappeared into the wings of his mind’s stage, like a character no longer necessary to the ongoing story line.

The metaphor of Reagan’s mind as a stage and his children as minor players exiting into the wings is consistent with his son’s attempt to construct a plausible portrait of a man who built his entire life as a theatrical performance. Not surprisingly, the book abounds in these stage and screen metaphors. Reagan is depicted as the producer of an elaborate self-dramatization with “the film unwinding in his mind.” Reagan’s father, given skimpy treatment in the script, is “left on the cutting-room floor.”

Ron asks us to visualize the president-to-be as a child of nine or ten, a bit delicate, highly sensitive to the routine marital tensions between his parents, yearning for a more ordered life, and so “creating in his mind a patchwork account of life and his place in it,” himself at the center of his story,

looming so large…that other people are reduced to props or bit players. He will go on refining this story throughout his life, in the process becoming not just its creator and star but director and story editor as well. Eventually that story will be buffed to a lustrous sheen, its rough spots worn smooth in the retelling, his own role ripened into one of unassailable nobility. As years pass he will, in effect, become his story.

In it he played only one role, ever, and he played it “unconsciously, totally absorbed in its performance.” He was “always the loner, compassionate yet detached, who rides to the rescue in reel three.”

Advertisement

In brief, he enters the world of let’s pretend as a child ill at ease with the genuine world of his family life. His son has put some real work into investigating the Reagans’ genealogy, starting with their origins in the Irish town of Ballyporeen. As president, Reagan was greeted triumphantly there during a brief visit to the old sod, and delivered a grand speech about the “flood of thoughts” loosened as he “looked down the narrow main street” once trod by his immigrant ancestors. Not quite so, says Ron. The O’Regans, he finds, were not of Ballyporeen, but from “a collection of rude huts” called Doolis, located a few miles westward. Hunting for ancestors thereabouts, Ron later discovered that Doolis had “reverted to bog, its meager dwellings long since returned to the elements from which they were fashioned.”

Ron also walked in his father’s footsteps in Dixon, Illinois, the falsely romanticized small town of his father’s youth. There he pondered the adolescent daydreams of the young lifeguard known as “Dutch” Reagan who hauled, by his own count, seventy-seven floundering swimmers out of the Rock River at Lowell Park, and we are reminded that Reagan was an accomplished and graceful swimmer in his youth. Ron is equally curious about his father’s obsessive desire in high school and college to become a football star and his willingness to labor doggedly at it, though he lacked the heft needed for success and mostly stayed on the bench.

Football glory eventually arrived when Warner Brothers cast him as the real-life Notre Dame football player George Gipp in Knute Rockne, All American. Hailed as “the Gipper” for years after George Gipp had disappeared from memory, Reagan had seen show business’s power to make the impossible dream come true: the world of let’s pretend had brought him a make-believe glory more glorious than the real thing.

After a fresh look at oft-told stories of his father’s youth Ron suspects a high malarkey content in some. He seems especially interested in exposing a fiction in what he calls “the iconic story” of Reagan’s youth. The story, which Reagan told in both his autobiographies, is about a cold night in 1922 when he was eleven years old and living in Dixon. Coming home one night, he found his father, Jack Reagan, passed out drunk on the front porch, “flat on his back…and no one there to lend a hand but me.”

This, Ron says, is his “Dad’s” story of his “coming-of-age moment, the hinge on which his young life swings.” As his father himself tells the story in Where’s the Rest of Me?: “Someplace along the line to each of us, I suppose, must come that first moment of accepting responsibility.” Accept it he does. “I got a fistful of his overcoat. Opening the door, I managed to drag him inside and get him to bed…and never mentioned the incident to my mother.”

Ron paraphrases this story with heavy sarcasm: He “did what heroes do: He manned up, took charge, muscled his pop to bed, and spared his mother’s feelings besides.” Ron obviously believes that Dad has here invented a big scene to improve his developing production of the Ronald Reagan story. He asserts that the story is heavily fictionalized, that “it didn’t happen that way—it couldn’t have happened that way.”

Why not? Because in 1922 Reagan had just turned eleven and was small for his age. He weighed barely 90 pounds; his father probably weighed 180. The boy wasn’t big or strong enough to drag his father anywhere, surely not up a narrow tricky staircase to his bedroom. This of course is only Ron’s version of what happened. Probably, he says, the shaken eleven-year-old awakened his slumbering father, who struggled to his feet and lumbered up to bed.

This story is embedded in the book’s most arresting passage—a confrontation, as it were, involving three generations of Reagan men: son Ron, famous father Ronald, and grandfather Jack. Ron clearly likes and admires his grandfather, who died before Ron was born. Ron just as clearly dislikes the way his father’s stories over the years darkened Grandfather Jack’s good name.

“Not that Dad intentionally set about destroying his reputation,” Ron writes. To the contrary, he often praised Jack’s good qualities, though repeated expressions of pity for him left the impression he was “a sad and troubling disappointment.” This portrayal of Jack as an alcoholic, Ron suggests, was another illustration of his father’s tendency to put more dramatic punch into his own life story by revising the facts:

Advertisement

Jack was reduced in Dad’s life reel not to bit player status but to the role of a stock character: the hardworking, hard-drinking son of Irish immigrants who pisses his dreams away in an endless round of clamoring dives and speakeasies…basically good-hearted, but undisciplined and weak.

In fact, Jack was a shoe salesman who was usually employed by the retail shops in farm towns where business soared and crashed with the shifting price of wheat, and where jobs, even for a hardworking shoe salesman, seldom lasted long enough or paid enough to cover purchase of a permanent home.

Ron dismisses the suggestion that Jack was a hopeless alcoholic. By the standards of his time, he was “hardly a world champion tippler,” and there was no evidence that he was a “true alcoholic,” though he sometimes drank too much. As if in apology for Reagan’s dismal treatment of Jack, Ron ends this unhappy generational tale with a graceful tribute to his grandfather:

For all his rough edges, his bawdiness and gimlet-eyed view of life, he possessed an innate dignity. He had a sense of style, a mind open to possibility. If he was weak, he was also principled. If he transgressed, he was, as well, a faithful and diligent provider.

How Ron could have known all this about his grandfather, dead seventeen years before Ron was born, is not clear. When a man tries to atone for indignities unjustly inflicted upon his grandfather, it seems heavy-handed to be unduly captious about it. Or, as Ron puts it, “The more I look into my father’s history…the more I’m inclined to cut Jack a bit more slack than his son did.”

President Reagan’s devoted admirers are bound to disapprove of his son’s less than reverent portrait of their hero. He will surely be denounced as a “liberal,” one of the foulest words in the conservative lexicon, and condemned for having declared himself an atheist. He seems to disagree with his father on most matters political and confesses that if anyone but “Dad” had been the Republican candidate in 1984, he would have cast his presidential vote for the Democrat, Walter Mondale.

He has already provoked a flutter in the press by suggesting that Reagan may have had symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease during his first term in office. Noting that his father was seventy-three when he ran for reelection in 1984, he recalls being alarmed by Reagan’s floundering performance in the first TV debate with Mondale—“fumbling with his notes, uncharacteristically lost for words,” and looking “tired and bewildered.” The second debate became a Reagan triumph when he disposed of the age issue with a witticism, delivered with a masterful Hollywood wink, promising not to “exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

“Whatever had been bothering my father,” Ron writes, “he seemed to have vanquished it, at least temporarily.” Reagan died of Alzheimer’s in 2004, twenty years after the Mondale campaign, but it is impossible to say when the first effects of the disease appeared.

Professional politicians, who tend to be quick to admire a star performer but slow to fall in love with one, still speak with admiration of Reagan’s ability to concentrate on matters he cared deeply about while staying almost utterly disengaged from everything else. In 1986 there was a flurry of speculation in Washington about Reagan’s being curiously out of touch with events comprising the so-called Iran-contra affair—a screwball arms-for-hostages scheme devised in the White House to illegally sell arms to Iran in return for Iranian help in freeing American hostages in Lebanon, and use the proceeds to fund Nicaraguan rebels.

This was an exceedingly complex and utterly illegal arrangement and as it became increasingly apparent that Reagan’s memory of it was dim at best, two possibilities were considered: one, that he had been criminally involved and was pretending memory loss to avoid impeachment; two, that in typical Reagan style he had never been interested in the problem involved in the first place and, so, was being completely honest about his memory failures.

It was in this year, 1986, that Nancy Reagan is said to have engineered the firing of Donald Regan as White House chief of staff. He was replaced by former Senator Howard Baker, whose first problem required him to weigh stories among White House staff people that the President was mentally confused. What Baker found was the same Reagan he had known for years: genial as ever, completely in command mentally, and interested only in matters about which he had always had the deepest concern. It was a judgment that put the question of mental disability to rest for the remainder of the Reagan years.

Reagan, be it noted, ended his presidency with notable successes in two of the matters that concerned him most profoundly. One was the growth of government social programs initiated by Franklin Roosevelt; when he left office Reagan had persuaded millions of Americans to distrust and fear their own government—“the problem, not the solution,” was his slogan. (The military, though operated by the government, was always excluded from this attack.) In the end, Reagan scored a lasting victory for the conservative movement by making it extremely difficult for government to undertake new social programs and hard to maintain the old ones.

His other overriding interest was the threat of nuclear warfare, which Reagan viewed as the gravest of all human problems. For thirty years, Washington’s national security establishment had assumed the inevitability of an unending cold war perpetuated by a nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union. Reagan shocked the professionals by pursuing nuclear disarmament. By heeding Mikhail Gorbachev’s pleas for someone in Washington to listen seriously to his hints that the Soviet Union was collapsing and powerless to continue the military standoff, Reagan confounded the experts and moved the nation toward the end of the cold war. It was a great achievement for a man whose political foes had dismissed him as an amiable simpleton.

Why his son chooses now to revive speculation about Alzheimer’s is puzzling. Ron is nevertheless a valuable expert witness for helping us understand the family life of a most notable American. Born in 1958 when Reagan was forty-seven, he has had fifty-two years in which to observe and reflect on his famous father.

As a child he has romped on the beach with “Dad,” and in the ancient tradition of insufferable adolescent malehood he has tormented a long- suffering father to the brink of violence. He has watched his father struggle against the urge to explode as his son’s hair grew “disturbingly long” and his wardrobe style shifted from “good boy” fashions to the thrift-shop shabbiness that was the uniform of the counterculture. As wholesale adolescence set in, Ron writes, he not only declared his atheism, but also told his hawkish father that he opposed the Vietnam War.

For Reagan the father it was the same trial endured by millions of parents in the 1960s and 1970s as they saw their children turning into campus Savonarolas and whiskery troubadours. That it could happen to Ronald Reagan, however, somehow seems bizarre. Reagan ought not to have know-it-all adolescent irritants around the house as everybody else did. Reagan was different, wasn’t he? It was beyond bizarre, it was grotesque that adolescent insolence could have brought Reagan to the verge of duking it out, fist to fist, with a teenage son. But so it did, Ron writes.

It was one of those dinner-table showdowns, so common in the 1970s, when Americans still had dinner tables and brought their most inflammatory opinions to them along with the food. Such was the setting for the one occasion in his life, Ron writes, when he thought his father “might actually take a swing at me.” Though he doesn’t recall what generated the heat, he describes a scene in which he rose to announce that he was going out for a drive, producing a commonplace fatherly reply: “You’re not going anywhere, Mister.”

There was some clumsy scuffling. Ron remembers his father cocking his fist and says he struck out defensively with his open palm as his father slipped and stumbled on the slick flooring. Young Ron slipped out the door, and combat ended. Peace talks began after a two-day cooling-off period.

Such was life even in our most distinguished families in those bleak years of American decline. Ron remembers his father telling him something that many a parent must have said to many a child in that time: “You’re my son, so I have to love you. But sometimes you make it very hard to like you.”

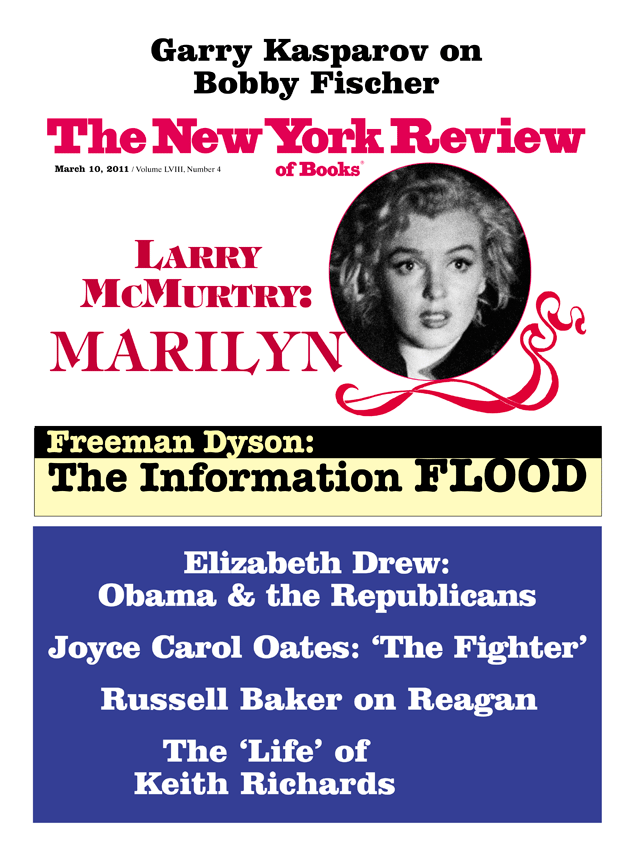

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know