Is studying the brain a good way to understand the mind? Does psychology stand to brain anatomy as physiology stands to body anatomy? In the case of the body, physiological functions—walking, breathing, digesting, reproducing, and so on—are closely mapped onto discrete bodily organs, and it would be misguided to study such functions independently of the bodily anatomy that implements them. If you want to understand what walking is, you should take a look at the legs, since walking is what legs do. Is it likewise true that if you want to understand thinking you should look at the parts of the brain responsible for thinking?

Is thinking what the brain does in the way that walking is what the body does? V.S. Ramachandran, director of the Center for Brain and Cognition at the University of California, San Diego, thinks the answer is definitely yes. He is a brain psychologist: he scrutinizes the underlying anatomy of the brain to understand the manifest process of the mind. He approvingly quotes Freud’s remark “Anatomy is destiny”—only he means brain anatomy, not the anatomy of the rest of the body.

But there is a prima facie hitch with this approach: the relationship between mental function and brain anatomy is nowhere near as transparent as in the case of the body—we can’t just look and see what does what. The brain has an anatomy, to be sure, though it is boneless and relatively homogeneous in its tissues; but how does its anatomy map onto psychological functions? Are there discrete areas for specific mental faculties or is the mapping more diffuse (“holistic”)?

The consensus today is that there is a good deal of specialization in the brain, even down to very fine-grained capacities, such as our ability to detect color, shape, and motion—though there is also a degree of plasticity. The way a neurologist like Ramachandran investigates the anatomy–psychology connection is mainly to consider abnormal cases: patients with brain damage due to stroke, trauma, genetic abnormality, etc. If damage to area A leads to disruption of function F, then A is (or is likely to be) the anatomical basis of F.

This is not the usual way that biologists investigate function and structure, but it is certainly one way—if damage to the lungs hinders breathing, then the lungs are very likely the organ for breathing. The method, then, is to understand the normal mind by investigating the abnormal brain. Brain pathology is the key to understanding the healthy mind. It is as if we set out to understand political systems by investigating corruption and incompetence—a skewed vision, perhaps, but not an impossible venture. We should judge the method by the results it achieves.

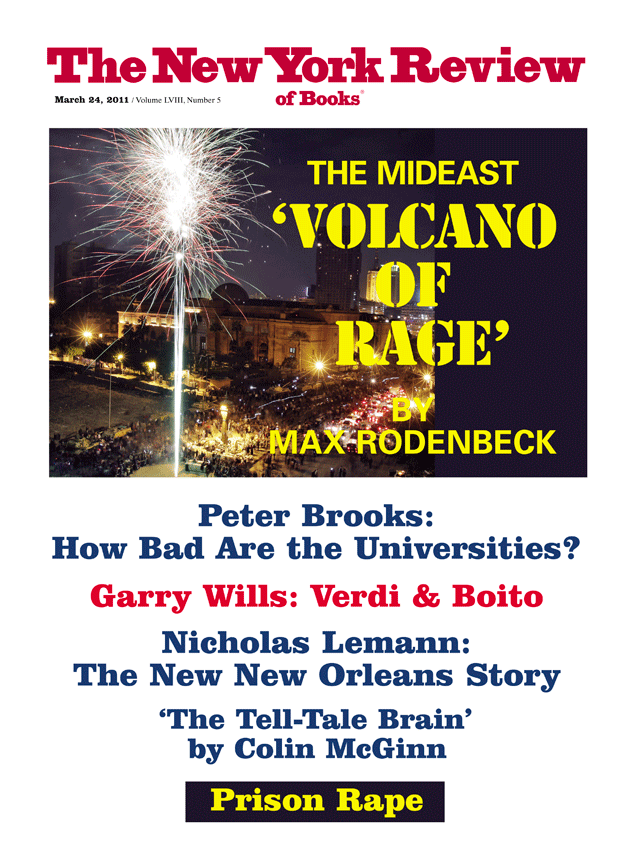

Ramachandran discusses an enormous range of syndromes and topics in The Tell-Tale Brain. His writing is generally lucid, charming, and informative, with much humor to lighten the load of Latinate brain disquisitions. He is a leader in his field and is certainly an ingenious and tireless researcher. This is the best book of its kind that I have come across for scientific rigor, general interest, and clarity—though some of it will be a hard slog for the uninitiated. In what follows I can only provide a glimpse of the full range of material covered, by selecting a sample of case studies.

We begin with phantom limbs—the sensation that an amputated or missing limb is still attached to the body. Such limbs can arrange themselves intransigently into painful positions. The doctor touches the patient’s body in different parts with a cotton swab, eliciting normal responses; then he touches the patient’s face and elicits sensations in the patient’s phantom hand, finding an entire map of the absent hand on the patient’s face. Why? Because in the strip of cortex called the postcentral gyrus the areas that deal with nerve inputs from the hand and face happen to be adjacent, so that in the case of amputation some sort of neighborly cross-activation occurs—the facial inputs spill over to the area that maps the phantom hand.

A contingency of anatomy therefore gets reflected in a psychological association; if the hand area of the brain had been next to the foot area, then tickling the foot might have caused a tickling sensation in the phantom hand. In another patient, amputation of the foot leads to sensations from the penis being felt in the phantom foot, including orgasm. Ramachandran devises a method to enable patients to move their paralyzed phantom arms, by using a mirror that simulates seeing the absent arm by reflecting the remaining arm: the brain is fooled into believing that the arm is still there and lets the patient regain control of its position. There are even cases in which the mirror device enables a patient to amputate a phantom arm, so that he no longer suffers the illusion of possessing it.

Advertisement

The chapter on vision covers such topics as visual illusion, the inferential character of seeing, blindsight, and the Capgras delusion, by which friends or relatives are seen as impostors. In blindsight an apparently blind patient can make correct visual judgments, thus demonstrating that visual information is still being received somewhere in the damaged brain. As Ramachandran explains it, this is the result of two visual pathways—the so-called old and new pathways—that can operate independently: the new pathway from the eyes is destroyed and with it conscious visual awareness, but the old pathway remains intact and conveys information unconsciously. Thus the patient takes herself to be quite blind, while still registering some visual information. The underlying anatomy of vision possesses a surprising duality of which most of us are never aware, and the upshot is the odd condition of blindsight.

In the rare Capgras syndrome a person will become convinced that close relatives are impostors, thinking that the real mother (say) is some sort of fraudulent twin. The sufferer’s eyes are working perfectly and have no difficulty recognizing the relative, but there is a stubborn conviction that this is not really her. Ramachandran explains this oddity as arising from a lack of nerve connection between the face recognition part of the brain and the amygdala, which deals with emotional response: since the perceived individual does not arouse the usual affective response, she cannot be the real mother, so the brain manufactures the notion that she must be an impostor. The explanation of the syndrome is thus anatomical, not psychological—a disruption in the normal neural connections.

Next we pass to “Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia,” a chapter I found especially rich. First Ramachandran has to provide proof that the phenomenon of synesthesia—in which stimulating one sense evokes stimulation in another, as when hearing a sound produces the visualization of a color—is real and that experiencing numbers as colored is not just a matter of childhood associations or vague metaphor. This he does by demonstrating that perceptual grouping of numerals can occur according to the color experiences the numbers evoke. He shows that the colors enter the mind as genuine sensations.

Then there is the difficult question of what explains synesthesia: Why should some people exhibit such an odd confluence of sensations? The answer again comes from anatomical propinquity: a main color center of the brain, V4, in the temporal lobes, is right next to an area dedicated to number processing—so synesthesia is conjectured to arise from cross-wiring of neurons. When a person with synesthesia perceives numerals there is an abnormal crossing over of nerve activity into the adjacent color area of the brain; the two areas are not insulated from each other, as they are in most people. One brain area excites the other, despite the lack of objective link between numbers and colors. In fact, it is surprising that this kind of thing doesn’t happen more often in the brain, because electrical potentials could easily spread from one area to another without something to damp things down.

More speculatively, Ramachandran ponders the connection between synesthesia and creativity, especially metaphor, conjecturing that it might be the basis of creativity. (It is found more commonly in creative artists: Nabokov was a synesthete; as a boy, he recalled, he associated the number five with the color red.) In a stylistically typical sentence Ramachandran writes: “Thus synesthesia is best thought of as an example of subpathological cross-modal interactions that could be a signature or marker for creativity.”

This leads him to the hypothesis that the fundamental mechanism of synesthesia might be shared by non-synesthetes, because of what he calls “cross-modal abstraction.” If you present subjects with two shapes, one rounded and one jagged, and ask them which of the shapes is called “bouba” and which “kiki,” you find that a majority assigns “bouba” to the rounded stimulus and “kiki” to the jagged one—as if some abstract form unites the sight and the sound. Ramachandran suggests that this is because the tongue makes different movements for the two sounds, which resemble the presented shapes. This “bouba-kiki effect” is held, by him, to explain, at least in part, the evolution of language, metaphor, and abstract thought—because, as we shall see, it involves purely structural similarities or analogies.

In a chapter boldly entitled “The Neurons That Shaped Civilization,” Ramachandran invests the famous “mirror neurons” (discovered in the 1990s) with remarkable generative powers. The mirror neurons that have been identified in the brain serve as the mechanism of imitation, he suggests, in virtue of their ability to react or “fire” sympathetically, and thus affect consciousness, when you are watching someone else do something: some of the same neurons fire both when you observe the performance of an action and when you actually perform that action. This is held to show that the brain automatically produces a representation of someone else’s “point of view”—it runs by means of mirroring neurons an internal simulation of the other’s intended action.

Advertisement

Observing that we are a species much talented in the art of imitation, Ramachandran suggests that mirror neurons enable us to absorb the culture of previous generations:

Culture consists of massive collections of complex skills and knowledge which are transferred from person to person through two core mediums, language and imitation. We would be nothing without our savant-like ability to imitate others.

The mirror neurons act like sympathetic movements that can occur when watching someone else perform a difficult task—as when your arm swings slightly when you watch someone hit a ball with a bat. For Ramachandran this specific neural circuitry provides the key to understanding the growth of culture; indeed, the mirror neurons are held to permit the evolution of language, by enabling imitative utterance. According to him, we need special inhibitory mechanisms in order to keep our mirror neurons under control—or else we would be in danger of doing everything we see and losing our sense of personal identity. We are, in effect, constantly impersonating others at a subconscious level, as our hyperactive mirror neurons issue their sympathetic reactions. Ramachandran sees a connection between the bouba-kiki effect and mirror neurons, in that both involve the exploitation of abstract mappings—across sense modalities in the former case or from perceptual to motor in the latter.

Ramachandran goes on to treat autism as a deficiency in the mirror neuron system: the difficulties of play and conversation, and the absence of empathy characteristic of autism derive, Ramachandran holds, from a failure of cerebral response to others. The autistic child cannot adopt the point of view of another person, and fails properly to grasp the self-other distinction, and that is what mirror neurons enable. Ramachandran claims confirmation of his theory in the lack of “mu-wave suppression.” In normal people the brainwave known as the mu wave undergoes suppression any time a person makes a voluntary movement or watches another perform the same movement, whereas in autistics, mu-wave suppression occurs only when performing actions, not when observing the action of others. The brain signature of empathy is thus absent in autistics. Autism accordingly results from an anatomically identifiable dysfunction—dead mirror neurons, in effect.

Ramachandran also postulates that the emotional peculiarities of autistics may be caused by disturbances to the link between the sensory cortices and the amygdala and limbic system, both centers involved in emotion. The normal pathways are blocked or modified in some way, so that the usual pattern of emotional response to stimuli is thrown off-kilter—trivial stimuli that human eyes register as uninteresting become affectively charged. Once again, anatomy rules, not psychology (so autism has nothing to do with bad parenting or Freudian struggles).

What can the structure of the brain tell us about language? In his treatment of this subject Ramachandran ranges over Broca’s area of the brain (responsible for syntax) and Wernicke’s area (semantics), various types of aphasia, the question of whether we are the only species with language, nature versus nurture, and the relationship between language and thought. Then Ramachandran squares up to the vexed problem of origins: How did language evolve? His solution is nothing if not bold: bouba-kiki supplies the magic solution. We need an account of how a lexicon got off the ground, and cross-modal abstraction is the answer. The bouba-kiki experiment

clearly shows that there is a built-in, nonarbitrary correspondence between the visual shape of an object and the sound (or at least, the kind of sound) that might be its “partner.” This preexisting bias may be hardwired. This bias may have been very small, but it may have been sufficient to get the process started.

In this view, words began by way of abstract similarities between visually perceived objects and intentionally produced sounds—we call things by sounds that are like what they name, abstractly speaking. Ramachandran introduces the word “synkinesia” to refer to abstract likenesses between types of movement—as, for example, between cutting with scissors and clenching the jaws. The suggestion, then, is that speech exploits not merely sight-sound similarities but also similarities between movements of the mouth and other bodily movements: the “come hither” hand gesture of curling the fingers toward you with palm up is said to be mirrored by the movements of the tongue as the word “hither” is uttered. This is not claimed to be the sole engine of language development, but it is said to provide an initial vital stage—how vocabulary began.

As to syntax, Ramachandran proposes that the use of tools afforded its initial foundation, particularly the use of “the subassembly technique in tool manufacture,” for example, affixing an ax head to a wooden handle. This composite physical structure is compared to the syntactic composition of a sentence. Thus tool use, bouba-kiki, synkinesia, and thinking all combine to make language possible—along with those ubiquitous mirror neurons. Just as fine-tuned hearing evolved from chewing in the reptilian jawbone structure (an “excaption” in the jargon of evolutionists)—as bones selected for biting became co-opted in the small bones of the ear—so human language grew from prelinguistic structures and capacities, building upon traits selected for other reasons. The jump to speech was therefore mediated, not abrupt.

Not content merely with explaining the origin of language, Ramachandran next ventures into the evolution of our aesthetic sense. He seeks a science of art. Enunciating nine “artistic universals,” he propounds what he allows is a “reductionist” view of art, attempting to provide brain-based laws of aesthetic response. Peacocks, bees, and bowerbirds possess rudimentary aesthetic responses, he suggests, and we are not so different. Thus we respond well to “grouping” and “peak shift”: we like similarly colored things to go together, and we are entranced by certain kinds of exaggeration of ordinary reality (as with caricatures) or other unrealistic images in art (like the Venus of Willendorf, as cited by Nigel Spivey in How Art Made the World). These biases result from our evolutionary ancestry as arboreal survivors—seeing lions through leaves and so on. Our taste for abstract art is compared to the propensity of gulls to be attracted to anything with a big red dot on it, since mother gulls have such a dot on their beak: “I suggest this is exactly what human art connoisseurs are doing when they look at or purchase abstract works of art; they are behaving exactly like the gull chicks.”

Throughout this cheerfully reductive discussion Ramachandran makes no real distinction between the arousal value of a stimulus and its strictly aesthetic value—he takes emotional power to be equivalent to aesthetic quality, at least at a primitive level. He eventually gets around to considering whether such a conflation is acceptable, making the brief remark: “It may turn out that these distinctions aren’t as watertight as they seem; who would deny that eros is a vital part of art? Or that an artist’s creative spirit often derives its sustenance from a muse?” In other words, he sees no important distinction between the aesthetic quality of a work of art and its attention-grabbing capacity—it’s all big red dots and enlarged buttocks (as in his discussion of sculptures of the Indian goddess Parvati), and the distinctions between, say, Titian and Picasso have no place.

Finally, we have an even more speculative chapter on the brain and self-consciousness. Again, we read of many strange syndromes: “telephone syndrome,” in which a man can only recognize his father when talking to him on the phone; “Cotard’s syndrome,” in which a person thinks that he or she is dead; obsessed individuals who want to have a healthy limb amputated (“apotemnophilia”); “Fregoli syndrome,” in which everyone looks like a single person; “alien-hand syndrome,” in which a person’s hand acts against his will. These curious cases are supposed to shed light on the unity of the self and self-awareness, even on consciousness itself. Ramachandran asserts that alien-hand syndrome “underscores the important role of the anterior cingulate in free will, transforming a philosophical problem into a neurological one.” The anterior cingulate, he observes, is a C-shaped ring of cortical tissue that “lights up” in many—almost too many—brain input studies.

What should we make of all this? It is undoubtedly fascinating to read of these bizarre cases and learn about the intricate neural machinery that underlies our normal experience. It is also, in my opinion, perfectly acceptable to propose bold speculations about what might be going on, even if the speculation seems unfounded or far-fetched; as Ramachandran frequently remarks, science thrives on risky conjecture. But there are times when the impression of theoretical overreaching is unmistakable, and the relentless neural reductionism becomes earsplitting. This is progressively the case as the book becomes more ambitious in scope. Ramachandran will often qualify his more extreme statements by assuring us that he is only proposing part of the full story, but there are moments when his neural enthusiasm gets the better of him.

For instance, mirror neurons are clearly an interesting discovery, but are they really the explanation of empathy and imitation?* Isn’t much more involved? Does an expert impersonator simply have more (or more active) mirror neurons than the average human? What about the ability to analyze an observed action, not merely repeat it? Where does flexibility in deepness of imitation come from (it cannot be those reflexive mirror neurons)? Imitation, moreover, comes in many forms, of different degrees of sophistication, and we cannot assimilate the trained mime to the baby’s reflex of poking out her tongue at the sight of her mother doing the same.

The discussion of art seems largely about another subject entirely—what elicits human attention. What about the place of abstract art in the history of painting? There is much more to it than gulls and red dots. In the case of language, one wonders how the bouba-kiki effect will explain words that have nothing in common with what they denote—the vast majority of cases. And how can anything about neurons firing in the brain account for conscious experience?

Ramachandran acknowledges no limit to neural reductionism, but there is a very big issue here that he slides over: the mind–body problem. His suggestion that by identifying the part of the brain involved in voluntary decision we turn a philosophical problem into a neurological one could only be made by someone who does not know what philosophical problem is in question—to put it briefly, whether or not determinism conceptually rules out freedom of the will. That question cannot be answered by pointing to one case of brain damage or another. Learning about the parts of the brain responsible for free choice will not tell us how to analyze the concept of freedom or whether it is possible to be free in a deterministic world. These are conceptual questions, not questions about the form of the neural machinery that underlies choice. His book has all the charm of an enthusiast’s tract—along with the inevitable omissions, distortions, and exaggerations.

There is another theme running through the book about which I think Ramachandran is insufficiently thoughtful. His subtitle is “A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us Human” and he repeatedly asks what makes us “unique” and “special.” The question is muddled. If the word “human” is just the name for the biological species to which we belong, then the answer presumably is our DNA—just as DNA is what makes tigers tigers. Species identity is a matter of genetics. If we ask instead what makes humans unique, then that question too is poorly posed: every species is unique, since no species is another species. Tigers are as uniquely tigerish as humans are uniquely human.

Ramachandran comes closer to his intended question when he speaks of our “marvelous uniqueness”: that is, he is asking what makes us superior to other species. I have three comments about this formulation. First, it risks anthropocentrism of a dubious (and possibly pernicious) kind: Aren’t certain other species superior to us in some respects—speed, agility, parenting, fidelity, peacefulness, or beauty? Just because a trait such as advanced mathematical ability belongs to us alone is no reason to claim some transcendent value for that trait. One would need to see some sort of defense of the claim that what is peculiar to us is thereby uniquely valuable. Is there really, in the end, a sensible notion of species superiority?

Second, Ramachandran operates with a rather rosy view of the human species—our darker side does not enter his calculations. What about our capacity for violence, domination, conformity (those mirror neurons!), deception, self-delusion, clumsiness, depression, cruelty, and so on? Where is the neural basis for those traits? Or are they somehow not part of our cerebral wiring? Isn’t the human brain equally an inferior brain?

Third, all this talk of the marvelous and superior is not scientific talk at all; it is evaluative talk, and not susceptible of scientific justification. Ramachandran is not functioning as a neuroscientist when he asks what makes us special in the evaluative sense; he is making judgments of value on which his scientific expertise has no inherent bearing. That is fine—but he should acknowledge what he is doing and defend it appropriately. He is just not clear what general question he is seeking to answer, eager as he is to delve into the brain and share its wonders with us.

Why is neurology so fascinating? It is more fascinating than the physiology of the body—what organs perform what functions and how. I think it is because we feel the brain to be fundamentally alien in relation to the operations of mind—as we do not feel the organs of the body to be alien in relation to the actions of the body. It is precisely because we do not experience ourselves as reducible to our brain that it is so startling to discover that our mind depends so intimately on our brain. It is like finding that cheese depends on chalk—that soul depends on matter. This de facto dependence gives us a vertiginous shiver, a kind of existential spasm: How can the human mind—consciousness, the self, free will, emotion, and all the rest—completely depend on a bulbous and ugly assemblage of squishy wet parts? What has the spiking of neurons got to do with me?

Neurology is gripping in proportion as it is foreign. It has all the fascination of a horror story—the Jekyll of the mind bound for life to the Hyde of the brain. All those exotic Latin names for the brain’s parts echo the strangeness of our predicament as brain-based conscious beings: the language of the brain is not the language of the mind, and only a shaky translation manual links the two. There is something uncanny and creepy about the way the brain intrudes on the mind, as if the mind has been infiltrated by an alien life form. We are thus perpetually startled by our evident fusion with the brain; as a result, neurology is never boring. And this is true in spite of the fact that the science of the brain has not progressed much beyond the most elementary descriptive stages.

This Issue

March 24, 2011

-

*

Patricia S. Churchland in Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us About Morality (Princeton University Press, 2011) is commendably cautious about the explanatory power of mirror neurons to explain imitation and empathy (see chapter 6), though she is in general a neural enthusiast. ↩