1.

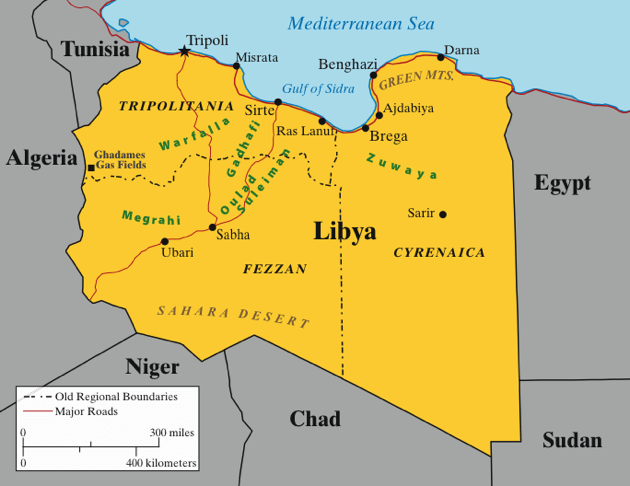

The small coastal Libyan city of Darna makes a charming break in the dreary 375-mile journey from the Egyptian border to Benghazi, the rebels’ de facto capital. On nearby bluffs nestled between the turquoise Mediterranean and the Green Mountains lie the ruins of the forums and churches Byzantium left behind, and in the city center you see the better-preserved white-domed shrines to Sheikh Zubeir ibn Qays and seventy-six other companions of the Prophet Muhammad. A plaque on the wall proudly declares that a Byzantine force slaughtered them in the year 69 according to the Islamic calendar, in the struggle between Islam and Christendom for the prized Cyrenaica, the eastern coastal region of what is now Libya.

For much of the twentieth century, the people of Darna revived this clash with the outside world. Italian Marshal Rodolfo Graziani set up camp in the town’s port as part of his pacification of an uprising led by a warrior-preacher, Omar al-Mukhtar, between 1912 and 1931. And in the 1990s and after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Darna reputedly sent more teenagers per capita on foreign jihads in Afghanistan and Iraq than any other town in the Muslim world.

So it was a surprise to find its townspeople so jubilant about American policy toward Libya. Even those with a jihadi pedigree expressed their support. In a small alleyway near the town’s main bank, Sufian bin Qumu, a former Guantánamo Bay detainee, nursed his Kalashnikov, hailed the United States as a protector of the weak, and pronounced the US-led bombardment “a gift from God.”

Solitary confinement in the prisons of Muammar Qaddafi or at Guantánamo Bay seemed to make many Libyans garrulous and extroverted, as if compensating for the years of lost human company. But bin Qumu’s six years under Guantánamo’s arc lights—he had been detained in Pakistan after the September 11 attacks—and three years in a Libyan cell the size of his cubbyhole loo in Darna have turned him into a recluse. He is convinced that Western intelligence agencies are still hunting him. His hennaed hair is combed flat, in a style uncommon in Libya, as if he were wearing a toupee. A pair of fluffy white slippers embroidered with cats lie on a rattan bookcase. Neighbors fend off intruding journalists by saying he has left for the front. “You know I know who you are,” he says a touch disconcertingly when we meet. He asks me to put away my tape recorder, saying it reminds him of his interrogators.

By his own testimony, he is an accidental jihadi. He was not religious when he left Libya; he did not go to the mosque. At the age of nineteen, he was press-ganged by one of Qaddafi’s army units trawling for teenage conscripts and sent to fight in one of the colonel’s savage border wars in Chad. After a decade he fled to Sudan, where he found work as a truck driver for a company owned by Osama bin Laden, and with it the solace that Qaddafi’s Libya had denied him. Recruited by al-Qaeda because of his military experience, he was dispatched to bin Laden’s camps in Afghanistan. He was caught by Pakistani forces after September 11, and transferred to American custody first in Kandahar and then at Guantánamo Bay; in 2007, he was transferred to Qaddafi’s torture chambers in Busalim prison in Tripoli. Every couple of months he was taken to the colonel’s external security organization headquarters in Tripoli for questioning by an American official. Bin Qumu remembers he exploded in anger when in August 2010 the official told him that Qaddafi was releasing him without charge.

The volte-face of Libya’s jihadis is no small achievement. Libyans were not minor adjuncts in al-Qaeda’s rise. At one time, Libyans ran several Afghan training camps and produced many of the group’s leading preachers. Abu Yahya al-Libi, a founding member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, which waged a guerrilla campaign against Qaddafi in the late 1990s, is considered al-Qaeda’s chief ideologue and bin Laden’s likely successor. An affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the name Arabs use for northwest Africa, has carried out attacks across North Africa.

Yet Darna’s struggle is not a mission of global jihad, but rather of local liberation from the Arab world’s most psychotic tyrant. The dalliance with al-Qaeda, bin Qumu says, was the result of Qaddafi’s abuses against his own citizens: the more violent the internal repression, the more radical the efforts to escape it. “The West has saved the Libyan people. We have to say thanks,” echoes Abdul Hakim al-Hasadi, another ex–Afghan fighter from Darna who was also captured after September 11, and interrogated by American guards in Islamabad. When we had lunch, he explained that a free Libya would provide the springboard for the West and the Muslim world to rewrite their troubled history and align in a common struggle against despotism.

Advertisement

Bin Qumu and al-Hasadi are among Darna’s new leaders, helping the doctors, judges, and university professors who make up the town’s council set up a local security force. Al-Hasadi, a one-time preacher who took up taxi-driving after Qaddafi released him from jail, now dines in the sumptuous hotel where the local council has set up base; after lunch he runs a camp in the Green Mountains above the town that has been set up in recent weeks to train teenage schoolchildren heading to the front. Beneath Sheikh Zubeir’s shrine lie the graves of seventeen martyrs, the earth still moist from the digging, who have fallen fighting Qaddafi’s forces first in Darna, which was captured by the rebels on February 17, and then in the oil towns along the Gulf of Sidra.

Neither man claims to aspire to an Islamic state. They say they favor elections, not imposed Islamic rule. They have pledged their allegiance to the National Transitional Council, the rebels’ representative body, and say they favor maintaining an alliance with America after Qaddafi’s downfall. A fortnight before he was killed battling Qaddafi’s tanks, which were then on their way back to Benghazi, another Libyan veteran of Afghanistan’s jihad, Rafallah Saharti, who had memorized not only the Koran but its ten variant chants, asked me why Western intervention had been so slow.

The separation of, on the one hand, the struggle of Libya’s local Islamists against Qaddafi and, on the other, the pursuit by some Libyans of global jihad has had a lengthy development. It began as soon as bin Laden unveiled his vision of a global Islamic superstate in the late 1980s, escalated after he declared his war on crusaders and Jews, and culminated after September 11 when some Afghan jihadis formally dissociated themselves from bin Laden, including those from the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group. I stumbled on this conflict in a Starbucks in Golders Green, a north London suburb favored by Muslims and Jews, soon after bin Laden declared war on crusaders and Jews in the late 1990s. Noman Benotman now runs a UK think tank, Quilliam, and wears a suit, but back then he was a Libyan jihadi leader traveling between London and bin Laden’s camps. He said he opposed al-Qaeda’s atrocities, culminating in September 11, because they enabled Arab autocrats like Qaddafi to crush local Islamist movements with Western approval.

The public renunciation of al-Qaeda I heard from Islamists once associated with it was even more strident among other Libyans. On the afternoon of March 31, I walked into a demonstration that young people in Benghazi had organized to denounce the colonel’s claims that their uprising was led by al-Qaeda. “If Omar al-Mukhtar [the leading opponent of Italian rule in the 1920s], Abraham Lincoln, and Charles de Gaulle are al-Qaeda, we are too,” shouted Mujdalia bin Ghor, an engineering student who had painted her fingers and forehead with the Libyan tricolor. Alongside her a woman in black gloves and black face-cover held a sign with an arrow marked “17 February Revolution” pointing right, and another marked “Qaeda and Qaddafi” pointing left, noting that both blew up airlines. “If we really had al-Qaeda, we’d have conquered Tripoli,” said a disabled schoolteacher, too paralyzed to participate, sucking apple tobacco irately through his water pipe in a nearby café.

By twilight, the protests against al-Qaeda and Qaddafi had swelled. Several thousand men and women, marching separately, chanted in rhyming couplets, loosely rendered from Arabic as:

No to Qaeda. No to Terror.

All Hail our Youth Guerrilla.Get out from where you dwell.

Show Your Face. Rise up. Rebel.Haya, Haya Hay-Alei,

Moussa Koussa ran away.

(The last is a reference to Qaddafi’s foreign minister, who fled to London on March 30.)

The decorum did not last long. After being drilled for four decades in the uniform mantra Allah, Libya, Muammar [Qaddafi] wa bas (alone), Benghazi has an air of exuberant chaos. A honking convoy of cars joined the rally, inching toward the protesters and drowning out the chants. A few boys in berets brandished their guns. A shopkeeper nearby set up an amplifier in his jeans outlet, competing with car stereos with his mix of Qaddafi’s hysterical speeches set to hip-hop. A motorcyclist reared his bike like a stallion beneath a colonial Italian colonnade.

After the honking cars came hundreds more protesters waving a sea of rebel Libyan flags and a smattering of Stars and Stripes and other coalition emblems. One boy had painted his face in multiple tricolors: the French on one side, the rebels’ on the other, and the Italian on his nose. A Union Jack covered his backside. “Obama saved me and my people,” explained Nassim Salim, a seventeen-year-old holding his star-spangled banner aloft. Next day at Friday prayers outside the courthouse, which served as the rebel headquarters, the preacher denounced al-Qaeda. The faithful incanted “God Is Great” and “Thanks America.” It was the first time I had seen American flags in Arab demonstrations that were not being burned.

Advertisement

Undoubtedly, the unlikely alignment of Islamism and America is in large part built on necessity; without Western intervention the rebel enterprise will collapse. If seen through to fruition—the colonel’s downfall—it could yet serve as the basis for deeper rapprochement, and mark the start of a healing process. But if the rebels’ enterprise fails, it could also go horribly wrong, deepening mutual mistrust and animosity.

For now the relationship stands on a knife-edge. Ten days before the demonstration, on March 21, Benghazi’s people had their first taste of failure. A convoy of Qaddafi’s tanks was moving north along the coastal road toward Benghazi’s university, sounding the call for a pre-positioned fifth column of Qaddafi supporters to act. Pro-Qaddafi paramilitaries and revolutionary committee members emerged from hiding and opened fire on people in the streets, creating mayhem.

The first civilian casualty was a thirty-one-year-old cartoonist, Qais al-Hilal, shot in the neck after finishing one of his trademark Abu Shafshufas, fuzzy-wuzzy caricatures of Qaddafi. Two journalists, one foreign and one local, were killed. A pro-regime sniper on a rooftop opened fire on several more journalists, until he was chased off by a former floor assistant from a department store in the provincial English city of Leicester who had bought his first gun two weeks earlier. A preacher, who had recounted to me his twenty-one years of torture in Busalim prison a few nights earlier, fled with his family to the Green Mountains after his name surfaced on one of Qaddafi’s hit lists. A Libyan migrant visiting from Vancouver frantically wrote a letter to President Obama pleading for him to save Benghazi and its rebellion. His request for a reply went unanswered.

If Qaddafi’s forces had reached Benghazi, there would not have been a slaughter amounting to genocide; but almost certainly there would have been a bloodbath. The back-and-forth of Katusha rockets that the two sides played to relatively harmless effect in the desert would have been murderous in the built-up areas of Benghazi, as would the colonel’s aerial and tank bombardments. At the eleventh hour, the Security Council declared a no-fly zone on March 17 and French air strikes destroyed Qaddafi’s tank convoy as it ground its way into Benghazi. But by that time, doctors had already recorded ninety-six deaths in the city.

2.

Over the past fortnight in Libya, I heard only one man dissent from the movement against Qaddafi, a Libyan Salafi in a pristine white tunic who follows the teachings of a Saudi religious group that preaches against defying leaders. The Western effort, he said, had escalated from a humanitarian to a military mission; it was killing, not saving, civilians, and he questioned why Western powers had not shown the same concern when Israel pummeled Gaza in the winter of 2008–2009. “We don’t want Mr. Cameron’s, Mr. Obama’s, and Mr. Sarkozy’s bombs,” he said. “Iraq was a much more modernized country than Libya, and look what a mess the allies left that.”

For the overwhelming majority, the more terrifying comparison with Iraq is to 1991, when following their liberation of Kuwait, Western powers backed Shia uprisings in southern Iraq, only to wash their hands when Saddam Hussein counterattacked. Thousands were killed and an estimated two million exiled as the Iraqi dictator reasserted control. A combination of US fear of a fundamentalist takeover (in this case by Iran) and a fear of mission creep that might upset a fragile coalition with Arab regimes underpinned American reluctance to intervene.

Could the same thing happen again? For now, the red line that the coalition has drawn in the sand has turned the east into a Qaddafi-free haven. His revolutionary committee bullies no longer interrupt diners in restaurants by beating the waiter for failing to dust the Great Leader’s obligatory portrait. And Qaddafi’s fellow despots confronting other popular uprisings think twice before applying such methods as using antiaircraft guns on civilian protesters.

But when the colonel pushes closer to Benghazi, the rebels start panicking over how far they can rely on their unlikely Western patrons. The US has dumped a leader whom for the last decade it has treated as an ally in the “war on terror,” and made common cause with an alliance that includes Western-oriented businessmen, but also former Guantánamo Bay inmates. After September 11, the colonel helped the United States track down Arab jihadis in Afghanistan, sharing intelligence extracted from torture victims. The United States responded by placing the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group on its terrorist blacklist.

Benghazi is now aswamp with Western delegations anxious to prop up the new rebel authority. The United States closed its mission in Qaddafi’s capital, Tripoli, and dispatched Chris Stevens, its number two official there, to Benghazi aboard a Greek boat loaded with armored cars. France, Qatar, and Italy have all recognized the rebels’ National Transitional Council as Libya’s legal authority. The UN, which on the weekend of April 2 flew a special envoy to meet the rebels, seems to do so in private on the grounds that no Libyan will remain safe as long as the colonel remains in power. “We’re pushing the responsibility to protect civilians to extremes,” a UN official told me. “When before did the UN support regime change of a member state?”

Judging by the US decision to withdraw from NATO’s regular policing of the no-fly zone, however, some American leaders remain undecided. The suspension of US Tomahawk missile attacks has been variously blamed on logistics, bad weather, and a fear of fatal mistakes. (In Kosovo, says a UN official, NATO bombings killed more civilians than Slobodan Milošević’s forces.) The rebels are trying to behave as politely as possible to the coalition. When a NATO plane struck a rebel convoy outside Ajdabiya on Saturday, April 2, killing thirteen people, the rebels apologized for the audacity of opening fire on a bomber. Opposition to external intervention has also waned as the predicament of the rebels grows more desperate. The Libyan resisters who once opposed proposals to send in Western forces now say openly that intelligence agents would be welcome. “They should come to verify there’s no al-Qaeda,” says a diminutive cross-eyed man with a wispy beard.

But weighed against such appeals is the counsel from fragile neighboring governments anxious to allay the Arab spring cleaning of autocratic rule. Algeria’s generals, National Council officials told me, provide Qaddafi’s western realm with gasoline, mercenaries from Polisario, the Algerian-backed movement to liberate Western Sahara, and above all propaganda about the risks of an al-Qaeda surge if the colonel is swept from power. Egypt, with its still-entrenched military leadership dealing with a fresh impetus of people power, appears as nervous of an incipient Islamist regime on its western border as it does of Hamas, the Palestinian Islamist movement, on its eastern one in Gaza. Had Egypt’s former president Hosni Mubarak still held power, it is likely that he would have shut its Libyan border and put the rebels under siege, just as he did when Hamas took power in Gaza.

And while the rebels have had much Arab support, the Great Leader continues to win backing further south. Central Libya’s tribes, including the Oulad Suleiman and the Warfalla, which hitherto stood on the sidelines, have now actively intervened to prevent the rebels from pushing west. The migrants from Chad and Mali on whom Qaddafi long ago bestowed passports are also repaying his favor with their loyalty.

With both sides increasingly dependent on foreigners to fight their battles, the war is incrementally burgeoning from an intra-Libyan struggle to a war of north versus south. The towns on the Libyan coast that seek allies against Qaddafi from across the Mediterranean are increasingly at war with a hinterland seeking to tighten its ties in Africa across the Sahara.

3.

For a time after the UN Security Council issued Resolution 1973, fears of Qaddafi’s return to the east receded. As in Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War, the no-fly zone appeared to have turned Cyrenaica into a de facto protectorate, crystallizing Libya’s partition. Rebels protested against NATO’s procrastination in coming to the defense of their last remaining redoubts in the west—Misrata and mountain towns along the Tunisian border. A creaky fishing boat, the Shahhat, made the two-day voyage from Benghazi to Misrata loaded with tin boxes of ammunition and shells under a blanket of medicines, but that seemed hardly sufficient to salvage the city, and anyway a Turkish vessel acting under NATO’s auspices blocked its path. But for the most part Qaddafi did not recapture the east.

The front line seemed more stable too. After failing to move west, the thawar, Libya’s undisciplined and untrained rebels, ceded control to General Abdel Fatah Younis, Qaddafi’s Special Forces commander for the past four decades, and his thousand or so men. Initially they seemed to have shored up the east’s defenses. The more intrepid—equipped with a few radios, GPS trackers, and the occasional Grad, were fanning off-road, avoiding the repeated ambushes that chased off the thawar. Though they were not gaining territory, they were not losing much either. The daily 125-mile swings of the pendulum from one end of the Gulf of Sidra to the next were stabilized in early April to a movement of a few miles in a week around Brega’s battered oil terminal.

Without more robust NATO intervention, even that limited progress now looks in jeopardy. In recent days, starting around April 7, the colonel has regained the initiative, opting for small mobile infantry strikes on rebel defenses with increasing efficacy. Multiple raids on the eastern oil fields have at least temporarily put them out of production, depriving the rebels of potential revenue just as they had found ways of selling oil. And after retreating from positions around Brega, the thawar are once again fighting in the streets of Ajdabiya, the gateway to the rebel-held east. Most of its people have fled east, with accounts of a new reign of terror. Humiliated husbands speak of wives who were raped; mothers lament sons who have disappeared.

A mere two hours’ drive from the front line, Benghazi still struggles to retain an air of normality. Its electricity, water, and petrol pumps are all functioning. The police are back in their barracks, and some have even surfaced on the streets. A few balconies tentatively sport the new Libya’s flag. Restaurants and cafés stay open later into the night. A leisure park and lake are closed, but the courthouse’s forecourt has become a playground for young families at dusk. Fathers precariously perch toddlers on the turret of a disabled tank, mold their little hands into V-signs, and take pictures.

But in recent days rebel losses on the battlefield have had internal echoes as well. While the colonel advances, the rebel generals squabble over who is in command; and while the oil fields burn, the National Council and its minions bicker over who should run the industry.

The infighting is reflected on Benghazi’s streets. After weeks of remarkable resilience and self-control, the volunteer spirit is showing signs of strain. Drivers who had queued at intersections are succumbing to the temptation to jump the lights. Members of the Youth Committee surface at dawn to sweep the courthouse square, but in the side streets rubbish is piling up. Vigilantes tussle over who should protect which marketplaces. Many food joints remain closed not because of instability but because the foreigners who used to fry burgers have fled. The council’s few directives—such as a call for Libyans to fill posts vacated by foreigners—are largely observed in the breach.

No one has been able to reopen the schools. The Doha-based satellite channel that initially mobilized people now has an almost numbing effect. Young men spend their days transfixed by rolling news from the oscillating front, as if watching alone might bring victory. A few go joy-riding. Doctors manning a mobile field hospital at the front fume that Benghazi’s youth party in the courthouse square, while rebel towns in the west burn. “We should be rationing, not rejoicing,” says Zahi Moghrebi, a member of the National Council’s political advisory committee charged with planning a road map for Libya’s post-Qaddafi transition to a utopian-sounding constitutional democracy. “We’re celebrating before the battle is won.”

The more wary warn that the listless lawlessness could soon spark anarchy. Abdul Hakin al-Hasadi, the veteran of the Afghan jihad who now runs his own training camp in Darna, fears that without a robust National Council to fill the vacuum, the surfeit of unlicensed weapons could trigger another Somalia, and has made his recruits swear affidavits to hand in their weapons as soon as the colonel falls. Parents pray for schools to reopen before their children are swept in the rush to the front. On April 5, gun-toting schoolchildren congregating on the dock chased away a Turkish aid ship with ambulances after claims that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan supported Qaddafi.

Having ceded at least some of the responsibility for prosecuting Qaddafi’s downfall to the outside world, the rebels already show signs of blaming the West for the hiatus. The demonstrations of gratitude in early April have turned to protests of accusation, after NATO took the reins of the allied effort from the US and ceased offensive bombing. Sorties increased, but the potency of the attacks sharply diminished as member states flinched from the prospect of collateral damage. NATO’s efforts to overcome its internal fractures, between the gung-ho such as Britain and France and the force-resistant such as Turkey and Germany, ensured that for the most the lowest denominator prevailed. Britain and France tried to revive the war fever momentum, but the more the war dragged on and the more the colonel adapted his tactics to guerrilla-style warfare the more cautious the alliance seemed to grow. “NATO hasn’t learnt how to transfer all its conventional might into fighting a nonconventional war without incurring civilian casualties,” says a Western security official in Benghazi. He was uncertain whether NATO had defined a limit beyond which it would rush to the rebels’ defense if the colonel’s forces advanced.

Protesters cast aside the foreign flags they had jubilantly waved days earlier. “NATO is no longer helping us,” wails Iman Bugaighis, a council spokesman. “There’s a discordance between the political message and what’s happening on the ground. We have cities full of people who are being bombed and shelled and left without medical aid. He could be in Benghazi soon. We can’t defeat him.”

Renewed NATO bombardment of Qaddafi’s tanks brought relief to Misrata and stemmed the colonel’s eastern advance, though it was not clear for how long. But after weeks of seeing their fortunes wane, rebel leaders who had champed against a stalemate that might have partitioned the country now almost welcome it for the respite it might bring. Some who had fumed against any accommodation with Qaddafi now ask why Western powers are not more vigorously pursuing a cease-fire, or even some form of reconciliation, which might let them preserve their current holdings in the east.

The alternative is ghastly. The sandstorm season in Libya is fast approaching, and with it the prospect of protection from NATO bombing. Under its cover, the colonel could yet send his pickup trucks, disguised with rebel flags, into Benghazi. Diplomats who had earlier said they were coming to stay are making contingency plans to flee within an hour’s notice, waving goodbye to free Libya.

The consequences of a takeover by Qaddafi of the east are worth contemplating. Inside Libya it would precipitate a humanitarian crisis and a mass exodus, probably of no lesser magnitude than that which followed Saddam Hussein’s suppression of his 1991 uprising. Externally, it would quicken the tempo of the Arab regimes’ counter-reformations, raising the bar on the levels of violence despots feel they can get away with. It would mark yet another jolt for badly dented US potency in the region; and it would turn the West’s newly acquired Islamist friends once more into embittered foes fighting for the defense of Darna and the Green Mountains , spawning another generation of Safim bin Qumus. The risks of al-Qaeda gaining a foothold on the Mediterranean coast stem not from the rebels winning, but rather from their defeat.

—Benghazi, April 14, 2011

This Issue

May 12, 2011