1.

Theodore Roosevelt, the youngest man to serve as president of the United States, and the youngest ex-president, also died young, at the age of sixty, in 1919. Apart from the four presidents who have been assassinated, only two of Roosevelt’s predecessors, James K. Polk and Chester A. Arthur, died younger than he did, as has only one of his successors, Warren G. Harding. The asthmatic child who grew to become the foremost American exponent of strenuous, combative virility lived at full throttle, even during the ten years after he left the White House—and he paid for it.

Edmund Morris’s Colonel Roosevelt covers those last ten years, concluding Morris’s three-volume biography and displaying the same penchant for detailed storytelling that dominated the first two volumes. Morris spares his readers little about Roosevelt’s dramas, including his physical torments. Recurrences of tropical malaria, a gunshot wound from a would-be assassin, painful abscesses from old injuries, a gruesome rectal hemorrhage (and subsequent surgery), bouts with rheumatism—Morris describes each one at length, until Roosevelt finally succumbs to a pulmonary embolism (or more likely, Morris contends, a heart attack). For Morris, Roosevelt’s bravery in courting and suffering these agonies testifies to his outsized personality. Yet as Morris also recognizes, Roosevelt’s will to power—which enabled him, as president, to transform the office—came with awful physical and emotional costs.

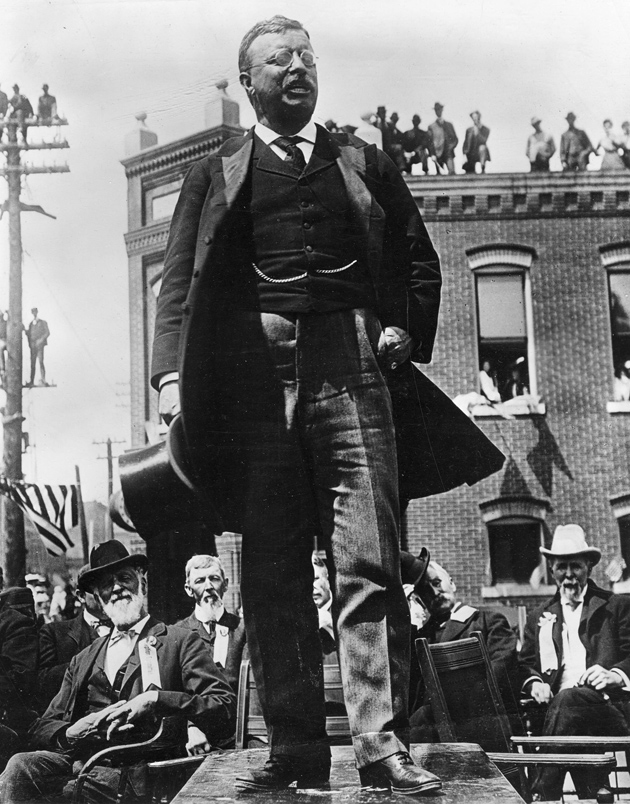

Theodore Roosevelt’s dogged courage and toughness are beyond dispute, and they did not fade in his later years. In 1912, while he was headed for a campaign stop in Milwaukee during his schismatic third-party run for the presidency, a lunatic shot him in the chest at close range. After refusing medical attention, TR proceeded to the rally, climbed to the podium, and gestured for silence as the blood soaked through his exposed shirtfront. Morris writes:

Waiting for the noise to subside, he reached into his jacket pocket for his speech. The fifty-page typescript was folded in half. He did not notice that it had been shot through until he began to read. For some reason, the sight of the double starburst perforation seemed to shock him more than the blood he had seen on his fingertips. He hesitated, temporarily wordless, then tried to make the crowd laugh again with his humorous falsetto: “You see, I was going to make quite a long speech.”

More than an hour later, Roosevelt came to the last page of his prepared remarks, and only then did he agree to be taken to the hospital. He survived because the bullet, which was headed straight for his heart, had had to pass through a heavy overcoat and a steel-reinforced eyeglass case as well as the lengthy typescript, before it nestled against his fourth right rib.

Formidable as he was, though, Roosevelt could not ward off the unsteadiness and pathos of his final years, and he brought a good deal of it on himself. After he voluntarily left the White House in 1909—he had conveniently, and in retrospect unwisely, adhered to custom and foresworn a third term four years earlier—Roosevelt preferred to be addressed not as Mr. President but simply as Colonel, the army rank he had earned with the Rough Riders in Cuba during the Spanish-American War (hence the title of Morris’s book). President no longer, Roosevelt proclaimed that he was determined to be an ordinary private citizen. But he was a proud and energetic man, still in the prime of life, and he took poorly to powerlessness.

Roosevelt’s idea of gentlemanly retirement was immediately to commence a perilous year-long safari to Africa with one of his sons, funded in part by Andrew Carnegie, on which it was estimated that he personally killed nine lions, eight elephants, twenty zebras, seven giraffes, and six buffaloes. (Those carcasses and hundreds more of big-game animals slaughtered by the expedition were duly salted and shipped home to be stuffed and displayed at the Smithsonian Institution and American Museum of Natural History, burnishing Roosevelt’s reputation as one of America’s most intrepid hunting naturalists.) Before he returned to the United States, he completed a tumultuous six-week public speaking tour that took him from Khartoum through the major capitals of Europe.

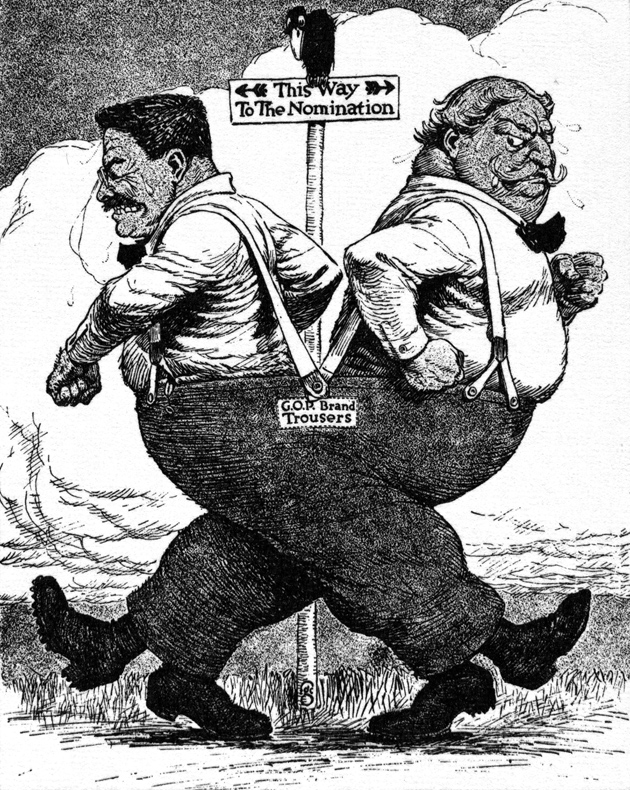

Once back in America, Roosevelt came to regard his anointed successor, William Howard Taft, as the betrayer of his Square Deal policies, and so he set forth to regain his job. But by the time Roosevelt broke publicly with the White House, at the end of 1911, the sitting president with all the perquisites of patronage had already sewn up the support of Republican Party leaders. Roosevelt won the overwhelming majority of the vote in the ensuing nonbinding Republican primaries, but it was insufficient to deny Taft renomination. Infuriated, TR bolted the GOP to run on the Progressive Party ticket and advance a program of governmental activism that he called the New Nationalism, which he had started propounding two years earlier.

Advertisement

Roosevelt had the pleasure of seeing Taft trounced in 1912—TR regarded the Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s victory as a foregone conclusion after Taft won the Republican nomination—but his Bull Moose candidacy ruined his reputation with the old-guard bosses and big-business conservatives who controlled the GOP. Morris does not speculate, but had Roosevelt tempered his outrage and grandiosity and bided his time, he almost certainly would have won the Republican nomination four years later. Instead, he spent a good part of those four years assailing President Wilson from the sidelines as a weakling in foreign affairs, only to be passed over by the Republicans once again in 1916. Roosevelt then had to suffer the humiliation of campaigning in support of the dull, cautious, moderately progressive GOP candidate Charles Evans Hughes, even as the crowds shouted “We Want Teddy!” (Drab though he was, Evans very nearly defeated Wilson, as Roosevelt surely would have done had he been the nominee.)

When the United States at last entered the Great War in 1917, Roosevelt lobbied hard for a military commission to lead a volunteer regiment in France, but the administration he had denounced for years turned him down. In his own place, Roosevelt proudly sent two of his sons off to fight, only to be devastated when his youngest boy, Quentin, was killed flying a combat mission over France.

Above and beyond his run at the presidency, Roosevelt had done his utmost, after he left the White House, to remain, as he put it famously, “the man in the arena.” Yet he lacked a firm political mooring and lurched furiously between safaris of one sort or another—joining another tropical expedition in 1914, this time along the uncharted Rio da Dúvida in Brazil, and very nearly perishing; delivering hundreds of political speeches and public lectures; writing an autobiography along with seven other books, as well as hundreds of articles, essays, and speeches on whatever artistic, literary, scientific, or political topic struck his fancy. Even as his body began seriously to fail, Roosevelt set his sights on yet another presidential campaign in 1920. But his ferocity of spirit could not make up for his accumulated political mistakes, and he was left to public and private exertions that succeeded chiefly in exhausting him. Quentin’s death was the last crushing blow: the Rough Rider who had loudly romanticized war as uplifting and even ennobling sobbed over his poor “Quentyquee.” “What made this loss so devastating to him,” Morris observes, “was the truth it conveyed: that death in battle was no more glamorous than death in an abbatoir.”

This is Morris’s writing at its best: compact and psychologically astute. Having lived with Theodore Roosevelt for half as long as Roosevelt himself actually lived, and having immersed himself in Roosevelt’s enormous output of writings, Morris knows the details of the man’s life and grasps his temperament better than any other biographer or historian ever has. With a few deft strokes, offset by dry wit, Morris brings TR alive—and even though he greatly admires his subject, he does not always place him in the most flattering light. “He used the strongest language,” Morris observes of Roosevelt’s martial instincts,

to emasculate men who hated militarism, or recoiled like women from the chance to prove themselves in armed action: “aunties” and “sublimated sweetbreads,” shrilly piping for peace. (The tendency of his own voice to break into the treble register was an embarrassment in that regard.)

On TR’s attitudes toward the poverty- stricken, Morris writes shrewdly that “like many well-born men with a social conscience, Roosevelt liked to think that he empathized with the poor. He was democratic, in a detached, affable way.” But if Roosevelt deluded himself, Morris continues, his aristocratic confidence also meant that “he lacked some of the neuroses of progressives—economic envy and race hatred especially. His radicalism was a matter of energy rather than urgency.”

In Colonel Roosevelt, Morris curbs the weakness for overdone, quasicinematic descriptions that occasionally marred his earlier writings. There is nothing here like the labored forty-page prologue to the preceding volume on TR, Theodore Rex, which describes in sometimes portentous and sometimes precious detail the two-day train ride in 1901 that carried Roosevelt back to Washington from Buffalo (where President McKinley had just been assassinated, and Roosevelt as vice-president was sworn into office). The pace of Morris’s storytelling can still be languid. But the major drawbacks in Colonel Roosevelt, as in the other two volumes, have more to do with Morris’s uneven handling of Roosevelt’s true vocation, which was that of a professional party politician.

Advertisement

Roosevelt’s adventures as an explorer, his writings as an amateur historian and naturalist, his gargantuan appetites for art, literature, and science, are all very interesting, and they are essential topics in any full-length biography. But what makes Roosevelt worthy of three monumental volumes is his political career and its legacy. Unfortunately, Morris the discerning biographer and skilled teller of stories is less helpful in explaining why Roosevelt succeeded and why he failed in public life. Not that Morris skimps on politics: election campaigns, factional rivalries, competing programs and philosophies, backroom machinations, all (or mostly) get related in full. Roosevelt’s drive, enthusiasm, and toothy grin—as well as his capacity to hate, and his insistence on seeing any social or political problem as cause for combat—helped define the man’s politics, and Morris describes them well. But Morris is less sure-handed—and at moments he seems uncomfortable—when he comes up against Roosevelt the calculating, contradictory, and cunning politician.

It is a fascinating and, finally, tragic tale. Roosevelt could never have become a successful president, let alone a statesman, had he not been a supremely successful party politician—a point that the historian John Morton Blum made nearly sixty years ago in his classic study, The Republican Roosevelt. During his presidency, Roosevelt’s political resourcefulness helped him earn his eventual place on Mount Rushmore. Thereafter, though, he squandered his political gifts, having lost the discipline required to use them effectively, and his pride and ambition undid him.

2.

It was unusual for a young man of Roosevelt’s background to choose politics as a lifelong career. Born in Manhattan in 1858 to genteel wealth, with a father who propounded the do-good Christianity that would eventually flower as the Social Gospel, “Teedie” could have been expected to join a high-minded private civic association or perhaps to turn his literary interests toward excoriating the vulgar parvenus of the Gilded Age. All the while he could have established himself as a well-heeled New York lawyer, his initial profession of choice. But the law bored young Roosevelt and he gravitated to the rough and tumble of electoral politics that offered opportunities to fight for and then exert real power. (He would claim for years that his motives for entering politics were entirely altruistic, but his fellow politicians knew better than to accept an altruist on his own stated terms.)

Roosevelt naturally became a Republican, and as an ambitious young state assemblyman, he advanced the conventional ideas of his class, above all that the chief problems besetting American government were the callous and corrupt Democratic urban machines with their low immigrant voters, and the only slightly less offensive graft-hungry politicos inside the Republican Party. When it looked as if one of the latter, the spoilsman and rogue senator James G. Blaine of Maine, would win the GOP presidential nomination in 1884, Roosevelt fiercely helped lead the fight against him. After Blaine prevailed, disgusted high-minded reformers, who became known as “Mugwumps,” left the party and backed the Democratic candidate, New York’s Governor Grover Cleveland. Whatever his drawbacks, the Mugwumps asserted, Cleveland at least was a man of decency and integrity—and sound economic conservatism. Roosevelt paused, swallowed his bitterness—and backed Blaine.

In the first important test of his political mettle, Roosevelt had apparently violated every standard of political honor. He himself said in private that he thought Blaine unfit for the presidency (although he had been a particularly effective secretary of state). His closest political associates—except for his friend and mentor Henry Cabot Lodge, who also supported Blaine—condemned him as a selfish, misguided conniver. And in the first volume of his trilogy, Morris also sounds bewildered and offended by Roosevelt’s decision. Morris does observe that Roosevelt may simply have been acting as a professional politician, but this doesn’t offset his dismay at what he calls TR’s flagrant immorality: “No adulterer,” Morris writes, “could more adroitly combine illicit lovemaking with matrimonial obligations than Roosevelt in his relations with both wings of the party in 1884.” Morris mugwumpishly concludes that Roosevelt must have acted out of self-interest.

In fact, it was far from clear that supporting Blaine was in Roosevelt’s best political interest, especially after Cleveland won the election. The Mugwumps claimed the credit, and the young assemblyman looked like a loser as well as a tool of corruption. Roosevelt thought that his party loyalty “meant to me pretty sure political death,” and for a time he assumed that his political career was over. Nor was Roosevelt, in choosing his party above his personal preference, thinking only about himself.

Roosevelt was absolutely certain that, like it or not, most Republican voters favored Blaine. He respected the process by which the party had made its decision and thus felt bound to respect that decision. Pursuing power in a democracy meant working by the means of organized political parties; party success required allegiance and discipline that surmounted personal opinions and considerations; breaking that discipline betrayed an unserious commitment to pursuing power. The only professional course for Roosevelt—and, on this view, the only democratic course—was to abide by and support the party’s nominee, with the hope that down the road, his own side, and perhaps he himself, would command the party.

The Blaine episode was Roosevelt’s coming-of-age as a professional politician. (Only in time did TR’s good fortune at Blaine’s defeat become apparent; Morris mystically says this shows that “fate, as usual, was on [Roosevelt’s] side.”) Soon after, he openly proclaimed party loyalty as a democratic virtue, and described high-minded nonpartisanship as “not only fantastic, but absolutely wrong.” The Mugwumps, Roosevelt later wrote, were dangerous elitists who “distrusted the average citizen and shuddered over the ‘coarseness’ of the professional politicians.” Nonpartisan do-gooders lacked virility—the quality he prized above all others and equated with courage—and in their ambivalence about the hard realities of political power were “almost or quite as hostile to manliness as they were to unrefined vice.” Roosevelt would press for reforms that served the public good, even if they displeased some of his fellow Republicans, but he would also strike and sustain the requisite alliances with practical, hard-nosed party chieftains.

By 1898, when he won the Republican nomination for governor of New York, Roosevelt had earned a reputation not simply as a hero in the Spanish-American War, but as a progressive who was a reliable party man. Once elected, Roosevelt pushed successfully for reforms, including stricter taxation of public utilities franchises, but he also worked closely on patronage and legislation with Thomas “Boss” Platt, the head of the state’s GOP machine. Neither the Boss’s creature nor his enemy, Roosevelt exhibited enough independence that Platt was happy to back TR’s nomination for vice-president in 1900—a booby prize that would conveniently remove Roosevelt from Albany. Roosevelt dutifully accepted his assignment, but also saw its advantages. Based on his experience as governor, he was coming to believe that only the federal government had sufficient power to tame the dynamic new forces of industrial America. And from the start, he coolly regarded the vice-presidency as a stepping stone to the White House. When McKinley’s assassination in 1901 shockingly made him an accidental president, Roosevelt was prepared to exercise the office with the political finesse and, if necessary, mercilessness required of any successful president.

An important party leader who had opposed putting Roosevelt on the ticket, McKinley’s political manager, Mark Hanna of Ohio, reportedly said in frustration to TR’s backers, “Don’t any of you realize that there’s only one life between this madman and the Presidency?” Roosevelt, no radical let alone a madman, believed mainly in the gospel of social works and upright conduct he had learned from his father. At a time when genuine radicals were preaching some variant of state socialism, Roosevelt insisted that “the true function of the State, as it interferes in social life, should be to make the chances of competition more even, not to abolish them.” Abraham Lincoln, whom Roosevelt venerated, could have said as much.

But Republican Party orthodoxy had changed since the Civil War, as the democratic nationalism of Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant gave way to a doctrine of laissez-faire that in theory abjured any role for government in society except to act as an impartial umpire in times of friction and conflict, but in reality simply cleared the path for large industrial and financial interests. Roosevelt, on the contrary, looked back to the Civil War era, understood the federal government’s potential capacities for serving the common good, and insisted that “the sphere of the State’s action may be vastly increased without in any way diminishing the happiness of either the many or the few.” He naturally viewed the presidency as the center of that action: “I believe in a strong executive; I believe in power,” he said. In government as in business, he believed, “the guiding intelligence of the man at the top” determined success or failure. He would later describe the president, with no false modesty, as “merely the most important among a large number of public servants,” but the president still had “more power than in any other office in any great republic or constitutional monarchy of modern times.”

Guided by a moral code of duty and personal honor instead of any political ideology, Roosevelt took up the fight against what he called “the selfish individual” who needed to learn that “we must now shackle cunning by law exactly as a few centuries back we shackled force by law.” Extremes of poverty and wealth appalled him and he ascribed these disorders not to impersonal social forces but to sly, effete men who combined selfishness with willful ignorance. Roosevelt’s great domestic achievements as president included prosecuting the antitrust Northern Securities case, settling the anthracite coal strike in 1902, winning passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, and regulating railroad rates under the Elkins and Hepburn Acts. None sprang from any social theory greater than what he called “social efficiency,” which he said derived loosely from a “love of order, ability to fight well and breed well, capacity to subordinate the interests of the individual to the interests of the community.” In foreign policy he translated “social efficiency” to mean military preparedness and active participation in global affairs, in order to ensure international orderliness and virtue—a civilizing mission that, especially in the Caribbean and the Pacific, can only be described as imperialist.

Yet Roosevelt’s pursuit of “social efficiency,” with all of its noble and dubious implications, would have been fruitless without his expert handling of the intricacies of partisan and presidential politics. Confronted, upon entering the White House, with a powerful rival in the kingmaker, Senator Hanna, who fancied himself a possible presidential contender in 1904, Roosevelt moved swiftly and relentlessly to assert his control over his party, regionally and locally as well as in Washington. The contest with Hanna, Roosevelt would later observe, was regrettable since they agreed about a great deal, not least on securing the Panama Canal treaty in 1903. TR considered the senator overall a force for good. But politics was politics. Concerning his takeover of the state party in South Carolina, one of many, Roosevelt remarked on how he “ruthlessly threw out all the old republican politicians” and substituted his own loyalists. Hanna died suddenly of typhoid fever early in 1904, and the threat to Roosevelt’s renomination disappeared; but by then, he fully commanded the levers of power inside the GOP.

Morris nicely describes the Roosevelt–Hanna rivalry in his second volume, although he focuses too much on TR’s canny use of Booker T. Washington as both a symbol and an adviser in order to undermine Hanna’s crucial Southern base of support. Morris’s blow-by-blow account of Roosevelt’s mastery of Congress likewise shows off his political guile to good effect. But Morris’s fascination with personalities and stories detracts from understanding Roosevelt’s purposeful strategizing in, for example, playing off Republican divisions over revising tariff rates (about which he cared little) in order to secure regulation of the railroads (about which he cared a great deal).

Morris describes the twists and turns of Roosevelt’s foreign policy copiously, but he could have accounted more exactly for how TR’s presumptions about the presidency and congressional indifference to international affairs repeatedly led him to bypass checks on executive power. Neither the Panama Canal negotiations nor the later Santo Domingo crisis (which led TR to promulgate unilaterally the expansive so-called Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine) affected much of the American public, and the outcomes can be justified. But Roosevelt’s conduct of “Big Stick” diplomacy called into question his oft-declared reverence for the Constitution.

Once he left the presidency, though, Roosevelt the political master was bereft. That he thought he could live without power was his greatest miscalculation. His hubris in believing that the good of the nation, indeed the world, hinged on his getting it back caused his tragic downfall. There are historians who take a kinder view and see in Roosevelt’s New Nationalist presidential campaign in 1912 the redeeming prophetic elements of what would become the heart of American liberalism through the New Deal and beyond. Those elements are certainly there to be found: Roosevelt made proposals for social insurance, workers’ compensation, women’s suffrage, an inheritance tax, and more, including a national health service drawn from existing government medical agencies.

Morris ventures no such connections between the New Nationalism and the New Deal. But he describes well the unreality of the Progressive Party convention, its delegates “scrubbed and prosperous looking, well dressed and well behaved, churchgoing, charitable, bourgeois to a fault.” The high-mindedness of 1884 had become the respectable crusading purity of 1912. But more to the point, Theodore Roosevelt, the hardheaded young pol, had become, out of his personal dejection and hurt pride, the latest crusader-in-chief, making the one move that was guaranteed to seal the end of his political career. In doing so, he guaranteed, despite himself, that the Republican Party would be an agent not of progressive reform let alone “social efficiency” but of the laissez-faire, pro-business conservatism of the Harding-Coolidge era that laid the groundwork for the Great Depression.

Here, in Roosevelt’s lifelong search for power gone haywire, is the key to his tragic later years, and their lasting importance to American politics. After the Progressive Party debacle of 1912 left the old guard in charge of the GOP, it would take a Democrat whom Roosevelt despised, Woodrow Wilson, to carry out some of the party’s reform proposals of 1912, including votes for women and the establishment of a federal income tax. Only many years later, after a Democratic Party led by northern liberals made an alliance with the remnants of TR’s progressive Republicans, would other reforms, including Social Security, came to pass, during the presidency of Roosevelt’s cannier, more enduring, and less egoistic distant cousin, Franklin.

Even then, the conservatism emboldened by TR’s prideful miscalculations, now fully entrenched among Republicans, would resist change ferociously, and succeed in blocking some of the social reforms of 1912 until our own time. Just as modern liberalism has been built, in part, on the first President Roosevelt’s achievements, so the history of the modern conservative Republican Party owes something to Colonel Roosevelt’s blunders in reclaiming his place.

This Issue

May 12, 2011