In 1992, four years after Jesse Jackson joined Stanford students in chanting “Hey hey, ho ho, Western Civ has got to go,” the Native American writer and activist Suzan Harjo, who had moved to Washington, D.C., in the 1970s, became the lead plaintiff in a case against the Washington Redskins football organization. She was joined by six other Native Americans, including the writer Vine Deloria Jr. This intended blow on behalf of Native American dignity—an attempt to force the team to change its name—took the form of a trademark registration case. Under the Lanham Act of 1946, any “mark” that is disparaging or that may bring a group of citizens into disrepute is not afforded the normal trademark protections.

At the time, sports teams at all levels were facing pressure to change such names. The Atlanta Braves kept theirs—arguably neutral or even positive—but in 1986 they had retired Chief Noc-A-Homa, a mascot who actually had a teepee in the bleachers of Fulton County Stadium and performed a war dance when a home team player hit a home run. The St. John’s Redmen became the Red Storm in 1994. Miami University of Ohio dropped the name Redskins in 1997. But those were colleges, and small ones. The Washington Redskins were then and are now one of the richest franchises in all of professional sports, selling many millions of dollars’ worth of their burgundy-and-gold merchandise with the warrior’s head in profile. The Merriam-Webster online dictionary labels “redskin” as “usually offensive,” placing it in the company of “darky,” “kike,” and “dago.” But the Redskins fought the suit for years, and finally, in 2009, the Supreme Court refused to hear the plaintiff’s appeal, letting stand a lower court decision in favor of the football team chiefly on the grounds that the plaintiffs had waited too long to file their claim.

The nickname had been the brainchild of George Preston Marshall, a laundry magnate and flamboyant showman who had bought the Boston Braves football team in 1932. As his second head coach, Marshall hired William “Lone Star” Dietz, a journeyman coach at the collegiate level whose mother was most likely a Sioux. It was in “honor” of Dietz, who coached the team for just two seasons and who at Marshall’s urging willingly put on war paint and Indian feathers before home games, that Marshall changed the team’s name to the Redskins. When Marshall, frustrated by Boston fans’ lack of support, moved the franchise to the nation’s capital in 1937, the coach was gone, but the team name stayed.

The move to Washington meant that the Redskins were now the young National Football League’s most southern team, its only one below the Mason-Dixon Line. Marshall, a native of Grafton, West Virginia, a small railroad town, had grown up with very Southern attitudes. In 1936, when he proposed to his wife, Corrine, he arranged a set piece to impress her, writes Thomas G. Smith in Showdown: he wooed the former MGM starlet “amidst fragrant honeysuckle while a group of African American performers sang ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginny'” (“Massa and Missus have long since gone before me/Soon we will meet on that bright and golden shore”). Attending them were two young black women dressed in costumes out of Gone With the Wind (published that same year) who brought them mint juleps. Marshall aggressively marketed the Redskins as the South’s team. He would be the last NFL owner to integrate his team and did so after years of heavy resistance and only because of government pressure.

Today, the National Football League is a huge corporation with estimated 2010 revenues of close to $9 billion. It is politically powerful, unfazed by occasional challenges to the famous antitrust exemption granted it by Congress in 1961. The exemption permits the league to control broadcasting rights to its games, which has helped it make those billions in ever-more lucrative contracts with the networks. If we don’t count the even more lucrative computer games, pro football is far and away the most popular of America’s sports, with nothing else even coming especially close. Last December, The New York Times reported that of the twenty top-ranked television broadcasts of 2010, eighteen were NFL games, including eight of the top ten.1 This was no aberration. It’s like that, more or less, every year.

Still, in the early days of professional football, with teams like the Kenosha Maroons and the Staten Island Stapletons—nearly fifty different squads in the 1920s, many of which were able to stay in business only a year or two—the very idea of a pro football league was mocked. Baseball was the national pastime, already inspiring writers like Ring Lardner; college football was beloved in the places where it still is today (Ann Arbor, South Bend), and many where it’s now an afterthought (the Bronx, New Haven). Boxing and thoroughbred racing rounded out the big four spectator sports of the day. Professional football barely registered.

Advertisement

It is largely for this reason that the NFL, in contrast to major league baseball, had actually had a few black players—the owners were desperate enough to accept them, and the public just didn’t care enough to lodge the usual protests about “mongrelization.” But in 1933, the league suddenly banned black players. It did so secretively, and no one would ever own up to the decision. For decades afterward, none of the game’s celebrated founding owners—George Halas of Chicago, Tim Mara of New York, Art Rooney of Pittsburgh, Tex Schramm of Los Angeles—would ever admit that there’d been a pact. But somehow, black players disappeared. Smith, a professor at Nichols College in Massachusetts, interviewed several owners and writes that evidence points to Marshall as the ban’s instigator. In a 1942 interview, Marshall argued that if black players were allowed to participate, Smith writes, “white players, especially those from the South, would go to extremes to physically disable them,” so they were kept off the field in their own best interests.

Marshall’s chief talent, it seems, was for creating spectacles. He hired cheerleaders and promoted other customs more associated with the college game, which today seem like fripperies at the professional level; he formed the league’s first marching band, which still exists (there are only two), and he produced a fight song, “Hail to the Redskins,” with music by the bandleader at the Shoreham Hotel, in whose large ballroom the songs of the Swing Era played. The lyrics were penned by Corrine, successfully courted that honeysuckle-and-julep-drenched night:

Hail to the Redskins,

Hail Victory,

Braves on the Warpath,

Fight for Old D.C.!…

Scalp ‘um, swamp ‘um, we will take’um big score….

For a few years, Marshall fielded winning teams. In 1937, the team’s first year in Washington, the Redskins won the league championship, defeating the Chicago Bears. Success continued apace, although the Skins were on the receiving end of the most lopsided loss in league history, a 73–0 humiliation at the hands of those same Bears in 1940. When the war came—Marshall, unsurprisingly, was an America-Firster—football, like baseball, was disrupted, but league play managed to continue. Sammy Baugh, the starting quarterback Marshall had drafted in 1937 (and who died just three years ago), had a deferment. In order to keep it, he had to fly back and forth from Washington to Dallas every week to his ranch to oversee the production of the beef that was part of the war effort and that justified his status. It wasn’t long before people began asking why a football player was given special permission to fly halfway across the country twice a week.

In 1945, the team again played for the league title, losing to the Cleveland Rams. That was the last championship game the Marshall-owned Redskins would reach. In fact, from 1946 until the early 1960s, when Marshall’s deteriorating health prevented him from overseeing day-to-day operations, the team amassed just three winning seasons. There were many reasons, but prominent among them was the virulent racism of the owner.

Professional football actually reintegrated the year before Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball. Robinson, a major football star at UCLA, had been considered by some of the more progressive football owners as a fine candidate for football integration until Branch Rickey drafted him for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Pressure was growing, in these postwar years, after blacks had fought in World War II, for things to change, and one of the more informative aspects of Smith’s absorbing book is his discussion of the pressures brought by sportswriters in the black press of whom one hears very little today—journalists like Wendell Smith of The Pittsburgh Courier, once the largest-circulation black daily in the country. Patiently but insistently, they chiseled away for years at athletic segregation. With Robinson lost to baseball, they focused their energies on Kenny Washington, another UCLA star, who played just before Robinson, in the late 1930s. After the war, Washington was still young enough to compete. And so in 1946, the Los Angeles Rams, and principal owner Dan Reeves, signed him along with another black player, Woody Strode.

Next, Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns acted, signing Marion Motley and Bill Willis. These players experienced exactly the same hardships Robinson later faced in baseball. However, unlike Robinson, they did not excel (except for Motley, a star for several years). Washington and Strode, it turned out, were both a bit past their prime and were not hailed by fans. Smith reproduces a chilling quote:

Advertisement

Strode did not relish being a racial pioneer. As Washington’s roommate on the road, he had to share the humiliation of eating and staying overnight at separate establishments from their teammates. “If I have to integrate heaven,” Strode told a reporter, “I don’t want to go.”

As the 1950s arrived, more teams starting signing African-Americans. A turning point came when the great Jim Brown, from Syracuse, joined the Cleveland Browns in 1957. Brown’s domination on the field was so thorough that all questions about the skills of black players were erased—except in the nation’s capital, whose team, Marshall said, would “start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.”

Washingtonians, it must be said, did not simply let all this go unremarked. Redskins fans, then as now, were among the most passionate in the league, and many ardent supporters among both the Georgetown set and the hoi polloi urged Marshall to rethink matters. Their view was given its strongest expression by Shirley Povich, the star Washington Post sportswriter. Povich (a man—Shirley was a male name as often as it was a female name in the early twentieth century) was Jewish and a native of Maine who originally moved to Washington to study law at Georgetown. He often wrote sentences like “Jim Brown, born ineligible to play for the Redskins, integrated their end zone three times yesterday.” Marshall remained unmoved. In 1959—around about the time some Southern states were reintroducing the Confederate stars and bars to their flags—Marshall changed the lyrics of the team song from “Fight for old D.C.” to “Fight for old Dixie.” The marching band’s standard pregame routine involved playing “Hail to the Redskins,” “Dixie,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner”—in that order. In 1960 and 1961, the team won just one game each year.

Despite these pitiful performances, the team still drew crowds large enough that Marshall (this should sound familiar) grew dissatisfied with old Griffith Stadium, which had stood since 1911 where Howard University Hospital is today, and began clamoring for a new park. Since the District of Columbia was administered by Congress in those pre–home rule days, this meant negotiating with the federal government. In due course, an arrangement was made for the construction of a 54,000-seat stadium at East Capitol and 22nd streets, on land owned by the Department of the Interior. Marshall signed a thirty-year lease.

Here, finally, was his error. The Kennedy administration hit town, and with it, a young and aggressive and very liberal-minded secretary of the interior, Stewart Udall of Arizona. Udall was a classic New Frontiersman. He was a gunner in World War II, a college basketball player at the University of Arizona, a self-described “Jack-Mormon” who did not follow his religion’s bans on alcohol and caffeine, and he was committed to integration. (He was also the brother of Morris “Mo” Udall, who served in Congress for many years and ran for the presidential nomination in 1976.)

Udall wasted no time in seeing his opportunity to force Marshall’s hand. Smith quotes from a memo the secretary sent to the President on February 28, 1961, just five weeks into the new administration’s tenure:

George Marshall of the Washington Redskins is the only segregationist hold-out in professional football. He refuses to hire Negro players even thought [sic] Dallas and Houston, Texas have already broken the color bar. The Interior Department owns the ground on which the new Washington Stadium is constructed, and we are investigating to ascertain whether a no-discrimination provision could be inserted in Marshall’s lease.

When such clauses were duly introduced, Marshall responded with a combination of bravado and apoplexy. He wanted a sit-down with Kennedy: “I used to be able to handle his old man,” he said, referring cryptically back to his Boston days. He asked rhetorically: “All the other teams we play have Negroes; does it matter which team has the Negroes?” During the summer of the Freedom Rides, the Redskins drama intensified. The American Nazi Party marched outside the new stadium, carrying placards saying “Keep Redskins White!” The NAACP and CORE picketed the stadium and Marshall’s house. Marshall insisted that the government had no right to tell him how to run his business. One wonders what Senator Rand Paul, among others today, might have said. By now, in any case, 70 percent of professional players are African-American.

In the end, Showdown, which is thoroughly researched, briskly written, and does a fine job of filling in this bleak episode in our cultural history, loses a bit of the momentum it has gathered because there is no great showdown, no Hollywood moment. Marshall saw that his hands were tied. Pete Rozelle, the NFL’s new, young, and PR-conscious commissioner, brokered a deal between Udall and Marshall by which the team was given until 1962 to start fielding black players. In the 1962 draft, the Redskins (who had won a single game in 1961 and lost twelve) chose the African-American Heisman Trophy winner Ernie Davis, from Syracuse. Marshall promptly traded him to Cleveland—but for Bobby Mitchell, another black athlete, so Mitchell became the first black Redskin (quickly joined by others). Davis contracted leukemia and died within months.

With Mitchell and the others, the Redskins started winning some games. They didn’t get really good again until the 1970s, under coach George Allen—the father of the former (and perhaps future; he’s running again) Virginia senator of the same name, the one who referred in 2006 to his Democratic opponent’s videographer as a “macaca.” Allen Sr. was close to President Nixon and had coached at Nixon’s alma mater, Whittier College. He even let Nixon call a play in a 1971 playoff game. It lost thirteen yards.

The team won three Super Bowls in the 1980s and 1990s, which made it one of the strongest franchises of that era. Under current owner Daniel Snyder—who bought the team in 1999 from the son of the previous owner, the flamboyant media tycoon and racehorse owner Jack Kent Cooke—success has been limited, to put it politely. Fortunes may be changing—the team is 3–1 so far this year as I write. But some things will not change. The team and its fans still often point to a 2004 survey by the Annenberg Center, which found that by a margin of nine to one, American Indians took no offense at the name Redskins.2 They have bigger problems to worry about. I admit to a mild curiosity about whether they’d feel differently if they knew the name was dreamed up by the sport’s most overtly racist figure, who even in his will (he died in 1969) stipulated that the Redskins Foundation that was to be created with most of his estate not direct a single dollar toward “any purpose which supports or employs the principle of racial integration in any form.”

This Issue

November 10, 2011

Our ‘Broken System’ of Criminal Justice

The Real Deng

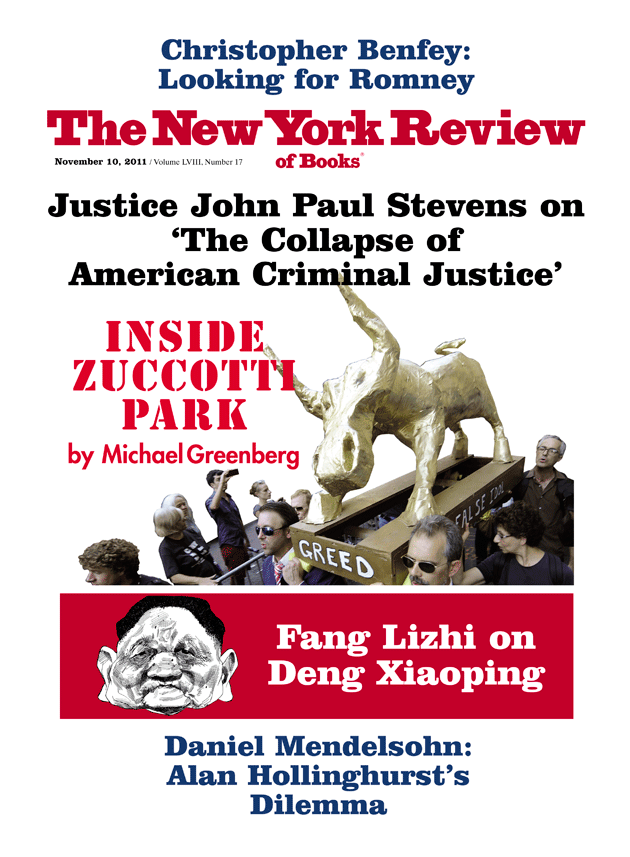

In Zuccotti Park