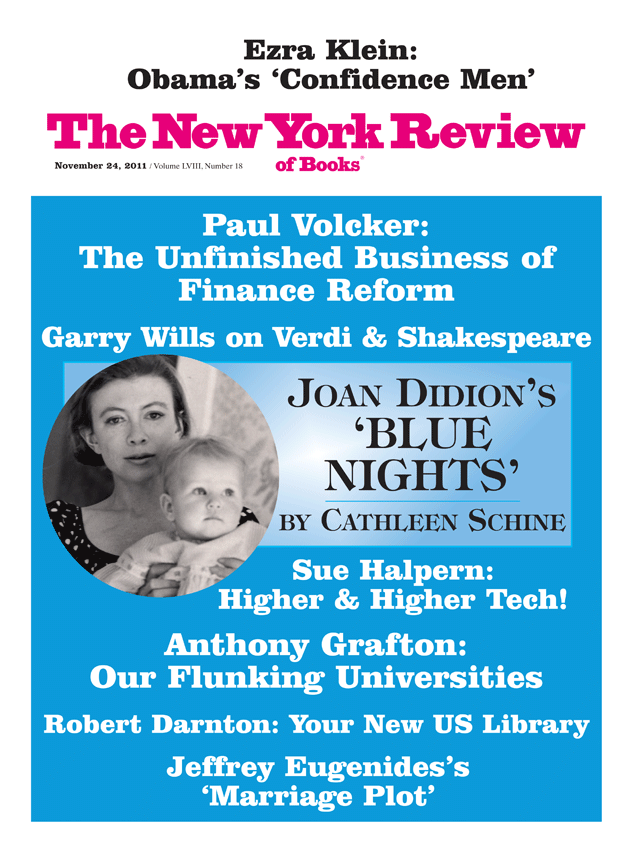

Blue Nights is a haunting memoir about the death of Joan Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, at the age of thirty-nine, death from an infection that began just before Didion’s husband, John Gregory Dunne, died suddenly of a heart attack at the dinner table. Quintana’s death was not sudden. It was not at the dinner table. It involved four intensive care units, four hospitals, two coasts, and twenty months. The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion’s account of the time following her husband’s death, described her frantic disbelief in the possibility of a world without the man she’d been married to for almost forty years. Blue Nights is something quite different. Blue Nights describes Didion’s descent into the inevitability of living in a world not only without her husband, not only without her daughter, but, finally, without hope. The book is possessed by an immeasurable, unrelenting despair. And it is alive with what is lost.

Didion is, to my mind, the best living essayist in America. Not a controversial view, although there are those who despise her work for its almost patrician accent. But Didion is an iconoclast, creating her own superior class of one. Her work has been for fifty years a testament to her ability to see through the clouds of rhetorical nonsense and get to the point, looking down from a soaring, preternaturally intelligent bird’s-eye view, then diving, a suddenly beady-eyed bird of prey. There are rats to be found everywhere. “Writers are always selling somebody out,” she has written. She writes beautifully about what is ugly and truthfully about what is false. In Blue Nights, as in The Year of Magical Thinking, she writes about death and the echoes it leaves behind. But in this new memoir, one of those echoes is the author herself.

Blue Nights is not offered as a redemptive book or as a memoir about the transformations one goes through after the death of a loved one (although Didion is transformed and describes many of those transformations); it is not offered as a chronicle of change and the wisdom that follows change (although Didion clearly does change after Quintana’s death and does, indeed, gain wisdom).

Could you have seen, had you been walking on Amsterdam Avenue and caught sight of the bridal party that day, how utterly unprepared the mother of the bride was to accept what would happen before the year 2003 had even ended? The father of the bride dead at his own dinner table? The bride herself in an induced coma, breathing only on a respirator, not expected by the doctors in the intensive care unit to live the night? The first in a cascade of medical crises that would end twenty months later with her death?

What appears on the surface to be an elegantly, intelligently, deeply felt, precisely written story of the loss of a beloved child is actually an elegantly, intelligently, deeply felt, precisely written glimpse into the abyss, a book that forces us to understand, to admit, that there can be no preparation for tragedy, no protection from it, and so, finally, no consolation.

This book is called “Blue Nights” because at the time I began it I found my mind turning increasingly to illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of fading, the dying of the brightness.

Blue Nights is a story of loss: simple, wrenching, inconsolable loss. The absence of Quintana becomes the most present thing in Didion’s life. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Didion famously wrote in The White Album. Blue Nights is about what happens when there are no more stories we can tell ourselves, no narrative to guide us and make sense out of the chaos, no order, no meaning, no conclusion to the tale. The book has, instead, an incantatory quality: it is a beautiful, soaring, polyphonic eulogy, a beseeching prayer that is sung even as one knows the answer to one’s plea, and that answer is: No.

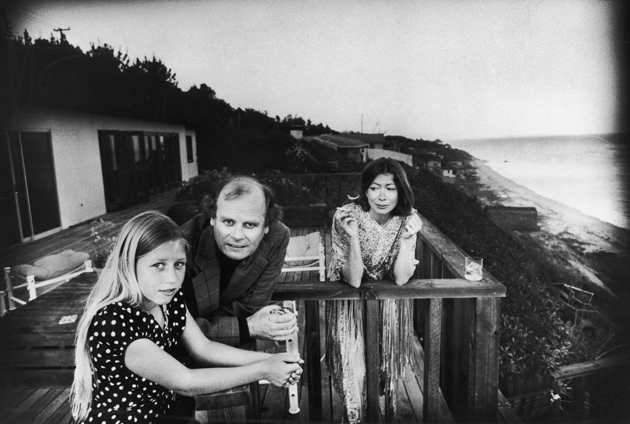

In 1966, a doctor called Didion and her husband to tell them he had found a baby for them to adopt. “I had been handed this perfect baby, out of blue, at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica,” Didion writes. The reception of the baby by her parents’ Hollywood community is reported in Didion’s poised, graceful, conversational style: “There were dresses in her closet, sixty of them (I counted them, again and again), immaculate little wisps of batiste and Liberty lawn on miniature wooden hangers.”

A new mother’s slightly baffled joy; the intoxicating freshness of those tiny dresses; the excess of the movie world; her own blindly happy absurdity. Didion has always had the literary gift of seeing small and seeing big while looking at the same object.

Advertisement

On the day the social worker comes to check up on the perfect baby and her adoptive parents, Didion carefully guides the social worker to a chair on the lawn. “The candidate for adoption played at our feet.” In one of the sixty dresses. But into this garden, and this pretty tableau Didion has carefully planned to impress the social worker, comes, almost biblically, a snake. The housekeeper sees it, snatches up the candidate for adoption, whisks her inside, and leaves Didion, like a political candidate, to fabricate lame excuses. It’s a game, she tells the social worker. There is no snake. She is telling herself the same thing: there is no snake. “There could be no snake in Quintana Roo’s garden,” Didion writes. “Only later did I see that I had been raising her as a doll.”

That first year of motherhood is described with a wistful impatience with her own naiveté. A dangerous naiveté, she suggests, bordering on stupidity. She and Dunne had been planning a trip to Saigon when the baby came. The year 1966 when, Didion notes, there were four hundred thousand US troops in Vietnam and American B-52s were bombing the North, could “not widely [be] considered an ideal year to take an infant to Southeast Asia.”

The christening for the new baby was held in the house Didion and Dunne were renting from Herman Mankiewicz’s widow in Los Angeles:

It was a time of my life during which I actually believed that somewhere between frying the chicken to serve on Sara Mankiewicz’s Minton dinner plates and buying the Porthault parasol to shade the beautiful baby girl in Saigon I had covered the main “motherhood” points.

Perhaps not, and as drugs and alcohol and psychiatric diagnoses begin to cloud Quintana’s life, Didion looks back and asks herself again and again what she could have done better. She had plenty of challenges. After Quintana left home and had a job, her birth mother and her sister got in touch with her, and then withdrew. What emerges from Didion’s account is her own sense of how little she could do as Quintana tried to deal with a family that was hardly her own. But Didion’s maternal devotion and love, which surely are the main “motherhood” points, spring from the pages of this book with passion. “Some of us feel this overpowering need for a child and some of us don’t. It had come over me quite suddenly, in my mid-twenties…a tidal surge.” Regarding the suggestions by some that Quintana had a “privileged” childhood, a fiery Didion writes,

“Privilege” is a judgment.

“Privilege” is an opinion.

“Privilege” is an accusation.

“Privilege” is an area to which—when I think of what she endured, when I consider what came later—I will not easily cop.

The book begins and ends at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where Quintana and the musician Gerry Michael were married on July 26, 2003. Didion the reporter is there, describing the pastel details, the “cucumber and watercress sandwiches, a peach-colored cake from Payard, pink champagne.” Quintana shakes the water off leis lifted from their boxes, stephanotis is braided into her hair, a plumier blossom tattoo shows through the wedding lace. Didion the memoirist is there, too. Stephanotis grew outside the Brentwood Park house they moved into when Quintana was in seventh grade; there were cucumber and watercress sandwiches at her sixteenth birthday party; there were leis in Hawaii.

Didion the witty observer is there, recalling dryly the buyer of the Brentwood Park house who said he could imagine his daughter getting married in the garden with its pink magnolia tree, then insisting the house be treated for termites with the gas Vikane. “The termites, I was quite sure, would come back. The pink magnolia, I was also quite sure, would not.” We recognize Joan Didion at the wedding. The Joan Didion of “Goodbye to All That,” her romantic elegy for a young woman’s New York City. The Joan Didion of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” an essay about Haight Ashbury in 1967 that is so meticulously distinctive and direct that it is one of the few pieces of prose that holds up from that overwrought moment.

We recognize Didion, the clear-eyed spectator of Old California’s demise, at the house in Brentwood Park when the flowers were alive and in bloom. The lushness of life is held out to us, a fresh, rich, sunny life of flowers lovingly enumerated and named : “agapanthus, lilies of the Nile, intensely blue starbursts that floated on long stalks. There had been gaura, clouds of tiny white blossoms that became visible at eye level only as the daylight faded.” But even in this description of the intensity of beauty and life, we feel the truth of loss. When daylight fades, these clouds of tiny white blossoms and the blue starbursts will be lost. And daylight, Didion makes us understand, always does fade.

Advertisement

When you think about Joan Didion, you think about place. It is in her reporting on subjects like California’s water or California’s murders that Didion has mused on her own Sacramento childhood, a somewhat delirious combination of the rambling joy of Huckleberry Finn and the arid, upright strength of a Willa Cather character. “Goodbye to All That” is one of her best-loved pieces, passed down from mother to daughter to granddaughter, a still-resonant ode to New York City. Back in Los Angeles in the Sixties, there is music and mayhem, a baby, a house, and always the city itself, the state, the state of the state. She tells the story of a difficult moment in her marriage as a report about waiting in Hawaii for a tsunami that never came. Didion’s work has always been an evocation of the specificity of place, the climate, the geography, the feel of the air, the slang, the heat, the architecture or lack of it.

In Blue Nights, however, all her landmarks are suddenly, terrifyingly, gone. A curtain in the emergency room of St. John’s hospital in Santa Monica is identical to an emergency room curtain in a New York hospital. The view of the East River, crowded with chunks of ice, from Beth Israel North hospital, is the same as the view of the Hudson River, crowded with chunks of ice, from Columbia Presbyterian hospital.

With Quintana’s death, Didion’s sense of place deserts her. It is something from the past. Like her house in Brentwood Park,

a period, a decade, during which everything had seemed to connect…. There had been cars, a swimming pool, a garden…. There had been English chintzes, chinoiserie toile. There had been a Bouvier des Flandres motionless on the stair landing, one eye open, on guard. Time passes. Memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember.

Time is a threat no dog on the stairs can guard against. Time doesn’t just move on, Didion implies. It passes—literally passes you by. What’s left are memories. “There was a period,” she says,

a long period, dating from my childhood until quite recently…during which I believed that I could keep people fully present, keep them with me, by preserving their mementoes, their “things,” their totems.

Her drawers and closets are filled with “the detritus of this misplaced belief.” Jet beads and ivory rosaries that belonged to her mother. Three old Burberry raincoats that belonged to her husband. Her daughter’s navy-blue gym shorts and a paper on Tess of the D’Urbervilles. “I find many engraved invitations to the weddings of people who are no longer married.”

In Where I Was From, her incomparable book about California, Didion rejects the legacy of her own past—the tough, neurotic, unpredictable, narrow, pioneering, stubborn superiority—even as she revels in it. In a piece about Georgia O’Keeffe, written in 1976, Didion admiringly describes the artist as “hard, a straight-shooter, a woman clean of received wisdom and open to what she sees.” That is a good description, of course, of Didion herself. Yet looking back at that essay today, what stands out more is the softness, the vulnerability of a very ordinary, lovely motherly pride. Quintana was with her on that trip to the Chicago Art Institute. She was seven. They stood together beneath a large canvas of O’Keeffe’s Sky Above Clouds. Quintana “looked at it once, ran to the landing, and kept on looking. ‘Who drew it,’ she whispered after a while. I told her. ‘I need to talk to her,’ she said finally.”

In Blue Nights, in a short, delicate prose poem of a chapter, Didion’s ironic reverence for the dusty, parched Sacramento of her youth as well as for the nearer past, the idyllic ten years in Brentwood, are gently, tenderly gathered up to show us:

What about the “Craftsman” dinner knife of my mother’s?

The “Craftsman” dinner knife on Aunt Kate’s table, the one I recognize in the photographs? Was it the same “Craftsman” dinner knife that dropped through the redwood slats of the deck into the iceplant on the slope? The same “Craftsman” dinner knife that stayed lost in the iceplant until the blade was pitted and the handle scratched? The knife we found only when we were correcting the drainage on the slope in order to pass the geological inspection required to sell the house and move to Brentwood Park? The knife I saved to pass on to her, a memento of the beach, of her grandmother, of her childhood?

I still have the knife.

Still pitted, still scratched.

I also have the baby tooth her cousin Tony pulled, saved in a satin-lined jeweler’s box, along with the baby teeth she herself eventually pulled and three loose pearls.

The baby teeth were to have been hers as well.

The history of California, so essential to so much of what she has written, is lost, dropped between redwood planks that have been torn up. Memories, so essential to her survival in The Year of Magical Thinking (her husband’s shoes in the closet for months after he died, for when he came back)—even this fantasy of solace has been ripped away. The mementoes cluttering her drawers were meant to “bring back the moment,” she writes. But now, they serve “only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.” The iceplant, the redwood deck, the “Craftsman” dinner knife, the reality of a life and the lives that came before it—all reduced to three loose pearls, to baby teeth, a reliquary for a lost child.

Memories—even these memories, the ones she has collected in this book—are as fragile and complicated and beautiful as one of the scraps of her grandmother’s lace, she tells us. They are as singular and, finally, as meaningless. There is no dress to trim with the old lace. There is no daughter. There is no future. Blue Nights is a deeply moving elegy to that void. There is so much life in the book, so much memory stored as carefully as those baby teeth, that the recognition of their futility is that much more devastating. “The enigma of pledging ourselves to protect the unprotectable,” Didion writes, a description of being a parent full of love and mystery and fear and pain. In the cruel reality of mortality, she is left with her daughter’s impossible and impossibly painful immortality:

I myself placed her ashes in the wall.

I myself saw the cathedral doors locked at six.

I know what it is I am now experiencing.

I know what the frailty is, I know what the fear is.

The fear is not for what is lost.

What is lost is already in the wall.

The fear is for what is still to be lost.

You may see nothing still to be lost.

Yet there is no day in her life on which I do not see her.

This Issue

November 24, 2011

Obama’s Flunking Economy: The Real Cause

Shakespeare and Verdi