There is a striking difference in register between the titles of the Hebrew and the English versions of David Grossman’s lengthy, ambitious novel. The portentous literary title in English stakes an epic claim; it has the grandiloquence that reminds one of titles like Gone with the Wind or From Here to Eternity, the refusal of specificity (think of The Good Soldier Švejk, Nana, or Hard Times) that insists this will not be the story of a mere individual or event, but one on the scale of “humanity,” of “everyman.” By contrast, the simplicity of its Hebrew title—“A Woman Running from the News”—announces another novel altogether, a realist novel of contemporary life, the story of a particular person at a particular moment.

The difference in the tone of the two titles mimics a struggle within Grossman’s novel between the author’s epic and realist intentions, a struggle on which the novel ultimately founders. Despite passages of courageous beauty, the work never quite becomes a coherent creation. It is a novel that, like its heroine, flees as much as it seeks.

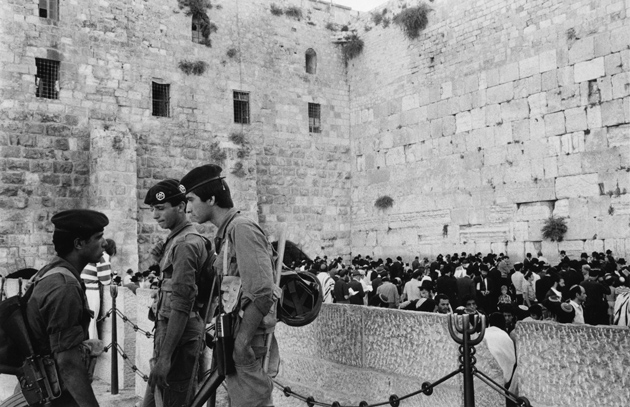

The epic note may be more comfortable for an Israeli novelist, since it is the timbre embraced, preferred, even required by the Israeli national story, which asserts that the modern state is founded on a timeless destiny. Grossman’s narrative shows the effect of a doctrinal national memory. Reading To the End of the Land feels like being plunged into a stranger’s dream, having to decipher the unfamiliar terrain of someone else’s private symbols and imagery.

The running woman of the Hebrew title is Ora, a member of the Jewish Israeli bourgeoisie of Jerusalem, wife of Ilan, an intellectual property lawyer. She is the mother of two grown sons, the elder, Adam, fathered by her husband. The younger boy, Ofer, is a child conceived with her husband’s best friend and her sometime lover, Avram, once a promising artist, whose life has been irreparably damaged after he was tortured by Egyptian interrogators during Israel’s 1973 war.

Ilan agrees to bring up his friend’s child as his own; Ofer’s real father refuses to see him and is only in intermittent contact with his former close friends. After Adam’s initial years of military service, he and Ilan have quit the household and are touring Latin America together, in flight from Ora. She has learned that Ofer and his army company had maltreated a Palestinian prisoner. There was an inquiry, but after Ilan “gently pulled a few strings,” Ofer had been demobilized without reprimand. Father and both sons characterize Ora’s distress at the incident as “unnatural.”

Nevertheless, Ora plans to celebrate Ofer’s freedom by taking him on a hike through the Galilee countryside. But Ofer suddenly reenlists during an emergency call-up, “insolent and joyful and thirsty for battle,” in order to join his comrades in an unnamed attack on the Palestinian territories. Ora, inescapably apprehensive, sets out to cheat death by refusing to seek any news of Ofer’s fate. She compels her estranged lover, Ofer’s father, to accompany her on the trek that she had planned for Ofer. She becomes gripped by the belief that they can keep their son alive if she remembers and describes every detail of his childhood. Her recital of “the story of his body and the story of his soul and the story of the things that happened to him” is a passionate attempt to create her own book of life, one in which her child will remain inscribed forever. It is, the reader grasps, a futile exercise, not because her son may die—we never learn his fate—but because of Ora’s credulous illusion that she knows her child more intimately than is possible. A mother is not an author; for a child she is part, one part, of the story of the things that happened to him.

These memories of Ofer, and of Ora’s relationship with her two lovers, relived during a camping trip in a nature reserve, take up most of the book; the author presents the story as an epic of maternity. She (and the Jewish male characters) are given no surnames, as if to suggest that this family is archetypal, modern matriarch and patriarchs in a ancient land. The only character given a surname is the family’s private chauffeur, a Palestinian taxi driver named Sami Jubran.

If To the End of the Land is an epic of motherhood, it is emphatically not an intergenerational saga. The parents of the three main characters are dealt with fleetingly; Ilan’s father is an army officer who regularly humiliates his family through exhibitionistic affairs with subordinate women soldiers. Avram’s father inexplicably loathes Avram and abandons the family. We learn nothing more of him. Ora’s Yiddish-speaking mother is described as “from the Holocaust”; we are given no information about her country of origin, social background, or family history. The three adult characters are rootless, despite their often repeated rhapsodies about the landscape and botany of Israel. Adam and Ofer don’t come to life as young men; their contemporaries and their own romances are mere sketches.

Advertisement

This foreshortening has a claustrophobic effect; the boys seem not to exist outside the family, while Grossman’s emphasis on Ora makes her omnipresent. She, in turn, seems unconvincingly fatalistic about their romantic and professional futures. Ofer’s only vision of his grown-up life is to have a “job where they’ll do experiments on him while he sleeps.” Neither parent addresses his aimlessness. They don’t question him about his social life as a soldier, though the army is a fundamental source of business, government, and job networking for Israeli men, who are subject to yearly reserve service until middle age.

The family circle is so tightly circumscribed that even Ora’s lover, Avram, is a quasi sibling. One becomes impatient for a member of this family to exchange a word with anyone outside it. They seem to exist wholly inside their “expansive old…house…surrounded by cypress trees” where the parents sleep in a bed designed and built by their son Ofer. With Ora virtually the only woman in the book and the principal source of perception, Grossman has to stake his story on the success or failure of her character.

Grossman clearly intends to honor and commemorate the quotidian acts of child-rearing—bathing, feeding, nursing, playing, schooling—but his intense focus on Ora monumentalizes her and miniaturizes the descriptions of these actions. As if she were a maternal variation of Midas, everything she touches turns to archetype; she can’t hang a pair of pajamas on a clothesline without evoking a comment about the “fullness of life.”

Ora exists largely through monologue, which creates another set of narrative problems. Her descriptions of her work of motherhood can seem awkwardly self-flattering; when she gains an insight into her troubled older boy, her husband clings “to her with strange fervor, and she thought, a hint of awe.” The boys are described as “joyous young people sprouting between them day by day,” though they seem anything but joyous; the older boy has a form of compulsive disorder, and the younger an obsession with Arabs. Improbably, no rumors reach the boys that they have different fathers; no friend exists to raise an eyebrow when Ora chooses to be incommunicado while her son is in combat.

The novel’s sense of enclosure, of confinement, is present even in the opening scenes of the book. Ilan, Avram, and Ora meet in a quarantined section of a hospital ward—alone except for an Arab nurse who brings them trays of food and medicine, at intervals crying like “an animal wailing.” The teenagers observe her weeping, but never think to speak to her. We assume that this is the moment of Israel’s 1967 war. Grossman declines to place us fully in time or society; the wars blur into a cloudy eternity of embattlement. Yet the author floods us with unexplained particularities of place and association: “the Nachlaot neighborhood”; the “Kerem,” the “Etzel,” the “Machanot Olim,” the “Yesud HaMaale camp”; “Um Juni or Beit Alpha or Negba, or Beit HaShita or Kfar Giladi”; Kinneret, where a volume of poems by a poet named Rahel is chained outdoors for visitors; Ein Karem (the family’s Jerusalem neighborhood); allusions to folk songs about calves that may or may not have special significance.

The reader might not guess that the hiking holiday Ora takes represents a national pastime. Yael Zerubavel’s book Recovered Roots describes how Zionist settlers of the pre-state period were given special classes in local nature and geography, part of a practice called

Yediat ha-aretz (knowing the Land) [that] did not simply mean the recital of facts in the classroom, but rather an intimate knowledge of the land that can only be achieved through a direct contact…trekking on foot throughout the land was particularly considered as a major educational experience, essential for the development of the New Hebrews.

For the non-Israeli reader, the association of hiking with laying claim to the land may be lost.

Trying to get some sense of Ora’s and Ilan’s Ein Karem neighborhood made me understand why Grossman either keeps the family indoors or whisks them out of the neighborhood. Ilan and the older son spend most of the novel touring Latin America, while Ora, Avram, and the phantom Ofer are removed to the pristine, pastoral Israel of a national park. But Ein Karem was once Ain Karim, a Palestinian village whose inhabitants were driven out in 1948. The neighborhood contains “one of the largest concentrations of Palestinian village construction in Israel and the West Bank,” according to a newspaper report, structures that are known to the Israelis as “architecture without architects.” The British Mandate government aimed to preserve Ain Karim, along with the villages of Lifta, al- Malkha, and Deir Yassin; the other three villages were completely destroyed.1 It was apparently a popular, affordable neighborhood for young couples in the 1970s. The older Ilan and Ora would have seen it become the source of intense struggles between preservationist residents and developers. The city government covered over Mamluke and Byzantine remains while the spring, supposedly the site where the Virgin Mary uttered the Magnificat, is now polluted, thanks to the public toilets built next to it.

Advertisement

Ora’s stone house with arched windows and decorative floor tiles must surely be one of the Palestinian villas. There her son Ofer develops a childhood obsession with Arabs, sleeping with a monkey wrench ready to attack them, making his foster father draw up precise population counts of each Muslim country, misspelling Arab “Arob” in his notebooks, “’cause they’re always robbing us.” In Grossman’s novel, the neighborhood is little more than a name and decor. Without its historical or social setting, we cannot fully grasp what living there might mean. We sense oppressively that we are being told one story to distract us from others.

What is striking in this sprawling novel with its chamber quintet of characters is that each relationship is warped, corrupted, truncated by the life Israel imposes on them. This is as true of the relationships between men and women, adults and children, as it is between Palestinians and Jews.

Grossman’s writing seems most assured in the passages describing the precarious, affectionate, and angry relations between Ora and the Palestinian driver Sami, who “is obliged to be at their service around the clock, whenever they need him,” leaving his home at three in the morning to fetch her teenage sons from parties. The relationship between them is as coded as a pas de deux, and is perhaps the most conventional relationship in the novel. Ora and family have been to Sami’s house in his village for family celebrations, but following the etiquette of social inequality, we see no reciprocal invitation. Sami is courtly and, with Ora, mockingly bitter: “half of Kiryat Anavim’s lands belong to my family,” he reminds her. Ora, for her part, wants to be magnanimous, “a gentle person.” “She would say, with a charming shrug, ‘only when it’s all over, the whole story, will we really know who was right and who was wrong, isn’t that so?'”

These passages are oddly reminiscent of American Civil War literature in Ora’s need to be justified and simultaneously enjoy her privileges: as Scarlett O’Hara says, “Uncle Peter is one of our family; drive on, Peter.” Like the black coachman’s, the Palestinian chauffeur’s driving is an emblem of the limits of his freedom; he can move, but only where ordered. As Uncle Peter must transport his owners, so Sami is summoned to transport Ora’s soldier son, Ofer, to join his unit in an “operation” against his own people.

Ora’s privilege within the novel extends to her freedom to repeat ranting soliloquies about Arabs:

Them and their lousy honor, and their never-ending insults, and their revenge, and their settling scores over every little word anyone has ever said to them since Creation, and all the world always owes them something, and everyone’s always guilty in their eyes!

It is unimaginable that Grossman would dare to allow the Palestinian character the same freedom in his thoughts about Jews, but in this and other passages, with steely candor, he reveals the pervasive intensity of the societal hostility to Arabs. Ora remembers sitting in Sami’s taxi while airport policemen hustled him off for a session of abuse, calling him a “shitty Arab.” On Ora’s hike, she stops in a guesthouse run by a group of fanatics who rapturously curse Arabs as an eternal enemy ordained by God before they offer a hot lunch.

Ora’s sons have absorbed this almost dogmatic enmity; Ofer screams and stomps, “Make them go away! Back to their own homes! Why did they even come here?” Ora describes the incident, saying that she gave her son a “seminar” on the conflict, but that is a scene Grossman doesn’t write. It is a missed opportunity to do more than just record these emotions, but to reflect on their meanings, purposes, origins, just as understanding explicitly where the family lives would add nuance to Ofer’s outbursts. Still, Grossman traces an unmistakable pattern; each of these tirades is delivered by a privileged or powerful person. The heroine herself, so vigilant over her own family’s situation, is quite complacent about Sami’s loss.

The finest scene in the novel, and the one in which Ora touches a freedom to be found nowhere else, takes place, paradoxically, in a secret clinic for illegal Palestinian workers, held in a Jewish elementary school auditorium. Sami has extracted a favor from Ora in exchange for being ordered to chauffeur her son to join his combat unit. Ora must help Sami negotiate a checkpoint in order to take a sick child for treatment. In a Rembrandtian nocturnal scene, Ora enters the auditorium of the “silent and dark” school, “illuminated only by the moon and the streetlamp.” As her eyes grow accustomed to the darkness, she makes out portraits of Israeli government figures on the wall, and gradually grows able to see human beings in the room:

Shadowy figures of men, women, and children dressed in rags, silent, submissive, dusted with refugee ash…. Ora freezes in terror. They’re coming back, she thinks…. She is convinced that her motion has made real the nightmare that always flickers in the distance.

Despite her terror, she observes in the darkness many vignettes of humanity and grace. Families are eating dinners warmed on portable stoves, people are sleeping on desks and chairs, “a man kneels down to bandage the foot of a man sitting on a chair…. From other rooms she hears stifled moans of pain and murmurs of comfort.” The child Ora has helped through the checkpoint is breastfed by a stranger—and Ora, a stranger, too, has protected this child who comes from a world beyond her clan. It is a moment suddenly charged with moral possibility.

Much less familiar than the painful relationships between Palestinians and Israelis are the effects on family life of living in an intensely military, Spartan society. When her second son is born, Ora says “emphatically” to his foster father, as he gazes on the child in its cradle, “I’ve made another soldier for the IDF [the Israeli army.]” The young sons play with a “sad phantom army” of plastic soldiers, while the parents give the toddler Ofer toy guns and ammunition belts, beginning the “meticulous daily construction of a brave fighter, erected on the fragile scaffolding of little Ofer.” Ora looks forward to Ofer’s return to civilian life, but she reflects “that they don’t really come back. Not like they were before. And that the boy he used to be had been lost to her forever the moment he was nationalized.”

As the boys grow older, the charm of the anecdotes of their childhood erodes; they grow unmistakably thuggish. Their feelings for Ilan alter; age renders him a mere civilian, while they treat Ora with affectionate contempt, as a naive, deluded bleeding heart who has never seen combat, calling her a “skirt.” (Grossman notably chooses not to explore Ora’s own military experience, apart from an anecdote of lovemaking with her future husband, an intelligence officer, when both are in the army. Her rank or role as a soldier is left unclear.) Ora watches uneasily as Ofer, a gifted carpenter, uses his skills to make a club, “the most efficient weapon in our situation.” Ora does not question her son about its uses. We only see him testing its strength on his own palm.

Like Ora, the reader is shielded from her sons’ real violence, which for her is rhetorical. The boys share jokes at family dinners about shooting Palestinians: Adam says, “shoot between their nipples,” and Ofer responds laughingly that he shot the man-shaped dummy in the stomach instead of the knees during his last target practice, excusing his misfire to the officer, “But, sir, won’t he go down this way, too?” Ofer half convinces his mother at lunch that “they had to come down on them once and for all, even if it obviously would not eliminate them completely.”

At another family reunion, Ofer describes how “one of our guys shot three boys throwing stones…broke their legs, one each, very elegantly,” and his brother suggests in passing, “Maybe you should aim so they’ll never have any children.” Ora is deeply upset by this conversation, and tries to “save her child” from the “barbarian” he has become, by making an ineffectual plea that he not “try to hurt someone intentionally.” She is presented as a dissenting voice, but her protestations are easily dismissed by her kin as ladylike and unrealistic, emerging from a self-serving moral vanity, a need to feel she is a fine person. That effect is heightened because Ora is the lone mother of the book; we can’t contrast her reactions with other women’s—a mother who might applaud her sons’ brutality, a mother ostracized for dissent, a mother more ruthless than her children. We don’t see a world in which Ora’s disapproval means taking risks. In order for her objections to have authority, she would have to examine how she herself is implicated in what her children have become. Placing Ora and Avram on the Israel trail and filtering the story through Ora’s memories alone send both characters and readers off on a holiday from the society and the militarized state.

Ora herself, to soothe her child’s fears of Arabs, takes Ofer to an Armored Corps site where he plays, entranced, on tanks, both ancient and new. She helps him climb up the turret of one; “he ran his fingers in awe over tracks, firing platforms, equipment chambers.” She encourages him, saying, “there’s lots more, we have loads of these,” conducting him into a kind of macabre nursery with a limitless supply of toys. She delivers her son to the army long before she takes him to battle in a taxicab. The scene with the tanks has an uneasy dreamlike quality; we see only Ora and Ofer, seemingly silhouettes on a giant screen that serves both to shield and to project reality. Are there other little boys and mothers who play here? What about little girls? We never see one in the book—Ora’s only playmate is a fleeting presence, killed in a car accident before the book opens. It is as if we were to see Dickens’s Gradgrind family of Hard Times without any daughters, without the bank, the pubs, the School of Facts, and the community itself.

An essay of David Grossman’s reveals how much this novel avoids in its portrait of Israeli children and parents. Grossman recounts:

About two decades ago when my oldest son was three, his preschool commemorated Holocaust Memorial Day, as it did every year. My son did not understand much of what he was told…. “Dad, what are Nazis? What did they do? Why did they do it?” And I did not want to tell him…. I felt that if I told him…something in the purity of my three-year-old son would be polluted, that from the moment such possibilities of cruelty were formulated in his childlike, innocent consciousness, he would never again be the same child. He would no longer be a child at all.2

Nevertheless, the Holocaust commemoration in Israel is staged as a nationwide public obligation, announced by siren blasts audible in every part of the country. Every citizen must stand motionless at the signal. Traffic is stopped for people to get out of their cars. Nursery school teachers are obliged to teach their charges about the Nazis to explain the adults’ behavior. Paradoxically, it is Grossman’s nonfiction work that gives us the more acute insight into Israeli childhood.

The novel gives no description of this rite of passage, but an essay by the chairman of the Early Childhood Department of Efrata Teacher’s College offers an admiring account of a model approach in the classroom. The kindergarten teacher explains that when Hitler

saw the Jews did not have a country of their own, he decided to kill them all. She emphasizes that the only place Jews can be safe is in the state of Israel, and asks the children “to think about those murdered…old people, babies, and children like you.” She dismissed the likelihood that this information might induce fear, insisting that the children are “not frightened very much” by what she chose to tell them.

If Grossman had explored his characters’ childhoods as richly outside as inside the household, we might better understand their behavior through the larger context. Ofer and Adam have been charged with the protection of their parents when they themselves are at their most vulnerable, while the state is subtly substituted as a refuge more trustworthy than the family. The child Ofer sleeps with a monkey wrench; he fears “Arabs,” but doesn’t seek shelter with his parents, relying on himself for safety. He has already been initiated, at age three, into understanding the world as a place of permanent endangerment, where parents are unable to rescue their threatened children. This would have made more sense of the boys’ rages and hysteria. We might then see the ambiguity of their passion to protect their parents, even as they later avenge themselves on those other parents helpless to protect their children—the Palestinians.

Grossman’s withholding of the political realities of Israeli childhood in the novel blunts the reader’s comprehension and response. He gives us an intimate experience of the cumulative effects of life in Israel on his characters, but the brilliantly idiosyncratic vignettes and intense scrutiny of one family obscure the ubiquity of the glorification of armed force, the relentless emphasis on the collective and group cohesion over individual values.

Ora wonders why she is more “loyal” to the state than to her motherhood, a bewilderment we share. She tells us that her boys change “when the army comes for them.” But it is difficult to grasp the irony of Ora’s illusion that the army is not already a presence in the private refuge of her household.

Yet from toy soldiers and paratrooper dolls, model tanks, displays of the emblems of Israeli army corps, pop songs from the armed forces radio station, school visits from soldiers, and picture books about army adventures, to teenagers taking state-sponsored trips to concentration camp sites in Poland, Israeli childhood educates for war. The crescendo of such trips is a visit to Auschwitz, where identification with the victims and with the group is achieved by a sort of hypnotic collective sobbing (the leaders call this process of induced catharsis “the coin dropping”). Observers describe fervent, and occasionally anguished, self-examination on the part of those who fail to weep.

Grossman has, though, given us an immensely convincing tragedy of a family disintegrating. His microscopic focus on the personal details of their domestic life together is a homage to their irreplaceable individuality, bringing to life their dilemma. They are, poignantly, creatures of their moment, wrought under particular ideological and spiritual pressures, not the eternal archetypes their culture asks them to be.

The terrible news Ora is running away from is not only that Ofer may have been killed in battle, but that something in him may have been killed at home. The novel is also, however, like its heroine, gently evasive. For all Ora’s obsessive remembering of her son, she never asks herself the essential question, the question that might alter altogether her sense of his life, and of her own: What are his true memories of her?