In response to:

The Hidden Lesson of Montaigne from the March 24, 2011 issue

To the Editors:

I share Mark Lilla’s delight with Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at An Answer [NYR, March 24]. In addition, I agree with his challenge to Ms. Bakewell’s belief that “the Essays has nothing to say about most Christian ideas.” On the other hand, Professor Lilla’s contention that Montaigne would not consider “total ignorance” a tragedy, that he embraced “mediocrity” as an ideal, and that he refused “to recognize the grandeur in our desire for transcendence” requires a highly selective and, in my view, misleading choice of passages from the Essays.

It is true that Montaigne thought it important to redraw the accepted portrait of what it meant to be human and to embrace a more nuanced view of what it meant to be wise. From this it does not follow that there are “hidden lessons” in the Essays of the sort Lilla imagines.

Rather than championing ignorance, Montaigne challenged the rationalists’ exaggerated confidence in reason; he questioned the value of theoretical knowledge in the absence of practical wisdom; and he criticized an educational system that enabled schoolboys to recite from memory the words of their lessons without knowing their sense or substance.

Rather than embracing mediocrity, Montaigne challenged humans to take on the most difficult of tasks, self-mastery. “Have you been able to think out and manage your own life? You have done the greatest task of all…. There is…no knowledge so hard to acquire as the knowledge of how to live this life well and naturally” (“Of Experience”).

And finally, Montaigne rightly ridiculed the desire for transcendence if the price to be paid was “to despise our being.” As he wrote in “Of Experience”:

It is an absolute perfection and virtually divine to know how to enjoy our being rightfully. We seek other conditions because we do not understand the use of our own, and go outside of ourselves because we do not know what it is like inside. Yet there is no use our mounting on stilts, for on stilts we must still walk on our own legs. And on the loftiest throne in the world we are still sitting only on our own rump.

Gresham Riley

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Mark Lilla replies:

Gresham Riley is right that Montaigne was above all concerned with challenging “exaggerated confidence in reason”: for him, as for his Enlightenment admirers, false opinion generated by faulty reasoning was the source of many human ills. However, like his Romantic admirers, he also went a step further, idealizing simple people who have no opinions or rely on tradition simply because it is tradition.

Throughout the Essays Montaigne distinguishes three classes of human beings: genuine philosophers (a race that no longer walks the earth), simple peasants, and those “half-breeds who have disdained the first seat, ignorance of letters, and have not been able to reach the other—their rear end between two saddles.” “These men,” he continued, “trouble the world.”

In politics especially, Montaigne preferred “the simple and incurious minds” who obediently follow the laws of religion and state to “those minds that survey divine and human causes” because they are “more docile and easily led.” This is the source of Montaigne’s conservatism, which has always confounded those intent on seeing him simply as an emancipator of human potential. He considered the human mind a dangerous thing and thought we must “bridle and bind it with religions, laws, customs, science, precepts, moral and immortal punishments.” He also believed that “there are few souls so orderly, so strong and wellborn, that they can be trusted with their own guidance,” and that for most people “it is more expedient to place them in tutelage.”

Ignorance can not only be politically advantageous, it can also bring us more individual happiness than relentless curiosity about ultimate causes. Montaigne remarks that “wine is no pleasanter to the man who knows its primary properties,” and of course he is right. But is it really true that “to inferiority, subjection, and apprenticeship appertains enjoyment and acceptance”? Montaigne thought so, which is why he wanted us to “return to this habit of ours.”

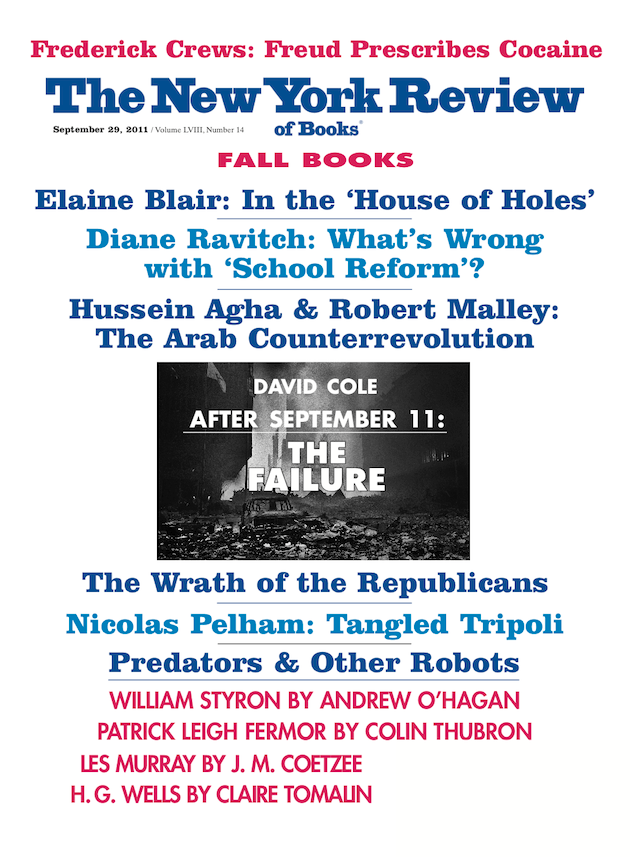

This Issue

September 29, 2011

School ‘Reform’: A Failing Grade

Coming Attractions

After September 11: The Failure