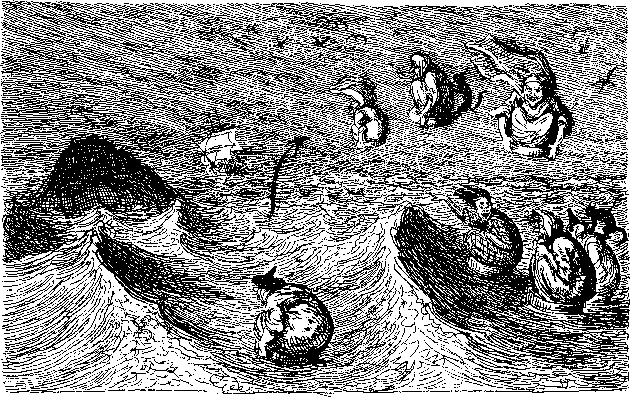

Judges and prosecutors have long struggled to assert that the law of the land applies equally to the wilderness of the sea, even as they’ve acknowledged that in international waters the law is in conflict with traditional maritime custom—especially the custom of drawing lots to decide who should live and who should die in desperate situations. A key case in England was Regina v. Dudley and Stephens (1884), in which the professional crewmen of the yacht Mignonette were convicted of killing and eating the cabin boy after their vessel had sunk in the South Atlantic and they had taken to the dinghy. The trial was obliquely commemorated by W.S. Gilbert in “The Yarn of the ‘Nancy Bell,’” in which an ancient mariner sings of how he has eaten most of the crew of his lost ship:

Oh, I am a cook and a captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And a bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s gig!

A close American parallel, cited in the later English case, was United States v. Holmes (1842). No cannibalism was involved, but the crew of the William Brown, bound from Liverpool to Philadelphia with a cargo of Scottish and Irish emigrants, pushed fourteen male passengers from an overcrowded lifeboat after the ship collided with an iceberg in mid-ocean, about 250 miles southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. When the twenty-two-foot boat was sinking under the weight of nine seamen and thirty-two passengers, lots were not drawn, and none of the crew members were thrown overboard. Alexander Holmes, the sole defendant in the case, was selected because he alone happened to be in Philadelphia at the time, though he was not the skipper of the boat and was merely following the orders of the first mate.

During the trial, much of the argument devolved on whether everyone aboard the lifeboat had been forced into a “state of nature” by their appalling circumstances, and were therefore beyond the reach of law, or whether they remained within “the social state” and so were answerable to the rules of conduct that apply ashore. The social state won the day, and Holmes was found guilty of manslaughter (a grand jury had rejected the charge of murder), but given a sentence of only six months and a $20 fine.

Charlotte Rogan has said that the William Brown case supplied her with the germ of The Lifeboat, her first published novel. She has moved the time of the action forward to 1914, so that the disintegrating world aboard her twenty-three-foot boat mirrors the fate of Europe as World War I breaks out. This time around, the ship is a sleek liner called Empress Alexandra, whose passengers are mostly upper-class Americans fleeing the war zone with their domestic servants. On the fifth day out from Liverpool, an explosion and fire send the ship to the bottom at roughly the same spot in the North Atlantic where the William Brown sank in 1841. Again, the lifeboats are too few and too small, and the frigid sea is a welter of the drowning and the drowned as Lifeboat 14 pulls clear of the foundering liner, with thirty-eight passengers under the command of Mr. Hardie, an able seaman.

The Lifeboat is both an enthralling story of survival at sea and a novel that is satisfyingly concerned with the character of its own storytelling. Grace Winter, the narrator, is twenty-two years old and newly married; watchful, intelligent, socially ambitious, with a core of cool self-interest. She is also on trial for her life. With two female codefendants, she stands accused of the murder of Able Seaman Hardie, who was tossed into the ocean a few days before an Icelandic fishing vessel rescued twenty-six starving and enfeebled survivors from the lifeboat.

The novel takes the form of Grace’s retrospective diary, written in her prison cell at the suggestion of her legal team, and designed by them to exonerate her of the charge of murder. But in the event (as we learn at the end of the book), the lawyers decide not to enter the diary as evidence, for Grace is an insufficiently unreliable narrator for their purposes. Too much of the truth leaks out from her account, and the jury might convict. So the book is an ambiguous document, at once self-exculpatory and incriminating, and this page-by-page doubleness forces the reader to weigh Grace’s words with unusual care and caution.

One passenger aboard the lifeboat, the crippled Mr. Sinclair, described as “something of a scholar,” quotes Aristotle on memory and recollection, and Freud on forgetting or suppression—a lesson that Grace takes to heart:

Advertisement

I think about this now, since writing this account has involved much recollecting. Sometimes I remember one occurrence, and only later does another thing that happened come to mind, which leads to yet another and so on, in a long chain.

Important events in Grace’s story—like her embarkation on the lifeboat, and whether a child fell to her death as an accidental consequence—are remembered differently each time they are revisited. In one version, her arrival on the boat is shrouded in the fog of general panic as the liner catches fire; in another, she recalls her husband striking some kind of bargain with Mr. Hardie; in another, a ship’s officer named Mr. Blake is also a party to the deal, in which a quantity of gold from the ship’s secret cargo may or may not be involved. Grace’s memory, suiting the moment as it adds and subtracts details to and from the story, is not egregiously self-serving or selective; it reminds one uncomfortably of one’s own, and when it reveals her as being snobbish or stony-hearted, such faults don’t alienate her from the reader’s sympathy, for there is always more to her than immediately meets the eye.

Grace’s preferred terms for other people’s personalities are “strong” and “weak,” like tea. She thinks of herself as strong, annealed over the course of the previous year by her father’s suicide when his business collapsed, her mother’s subsequent madness, and the family’s sudden transition from a grand house with servants to squalid tenement lodgings. Her sister has acquiesced to fate by finding employment as a governess in Chicago, while Grace has secured for herself a rich husband, first spotted in the society pages of a newspaper, where he was pictured with a fiancée. If all this sounds rather implausibly schematic, so it is: Charlotte Rogan is not unfriendly to cliché, but at her best she writes her way through hackneyed and archetypal situations with such conviction that she refreshes them and gives them the power of myth.

Much of Grace’s treasured strength is rooted in her instinctive opportunism. Whether in the lifeboat or the Boston courtroom, she has a chameleon’s ability to adapt to new circumstances. When first met, she is, she says, a “practical Anglican,” by which she means a churchgoing agnostic with a moral creed. Aboard the boat, she quickly attaches a kind of godhead to Mr. Hardie, a “savior,” for his apparently encyclopedic knowledge of the sea and all its ways. When this god fails, he becomes a “devil,” and Grace’s religious loyalties are transferred to the ocean itself and its massive indifference to humankind. These three stages chart the gradual descent of the lifeboat and its occupants from the “social state” to the “state of nature,” from life in a world governed by and answerable to the law of the land, to life on the barbaric frontier of the lawless sea.

Most of the book’s narrative energy comes from its intent depiction of the survivors as they steadily deteriorate from civilized men and women into savages. By the twelfth day of the ordeal, eight of the boat’s original complement have either died or stepped overboard as a result of Mr. Hardie’s apparently rigged lottery, and the remainder are starving and thirsty, when a small flock of unidentified birds tumbles out of the sky and into the ocean, from where they are scooped up by grateful hands, with the religious thanking God for a timely miracle. “We were covered in down and offal,” Grace writes.

I had the fleeting image of myself as a predator, until I looked around me and realized that we were all predators and that we always had been…. I was not alone in feeling a strange sympathy for all that lay around me: the sky, the sea, and the boat full of people, all of whom now had blood dripping down their chins and lips creased with painful fissures that cracked and bled when they chanced to smile.

The bird-feast marks the point at which the lifeboat floats free of legal constraints, of social custom and manners, and enters the terrain of nature red in tooth and claw.

In theme, at least, The Lifeboat has obvious similarities to Lord of the Flies, if one can imagine Lord of the Flies stripped of William Golding’s passion for natural detail, his intricate theology, the way he makes the long ironic shadow of Ballantyne’s The Coral Island fall across his own tropical island, and his finely individuated cast of prep school boys. The Lifeboat is a bare-bones novel that stands or falls by the mesmeric (or otherwise) qualities of a single character.

Most of the secondary characters in the book are little more than diagrams. Mrs. Grant, also on trial for murder, is described as “sturdy,” and aboard the lifeboat is seen only in two functions, either mothering the other women or questioning the orders of Mr. Hardie. Mr. Sinclair, the crippled “scholar,” is there to quote from classical authors, and when that job is done, he conveniently hauls himself overboard. Most puzzling, and least satsfactory, is the splintered personality of Mr. Hardie.

Advertisement

He has a “rough seaman’s voice,” and much of the time speaks in the dialect of a children’s-story pirate, saying “aye” for yes, “yay” for no, “ye” for you, “yer” for your, and puncturing his sentences with the British-sounding “bloody.” “Row yer bloody hearts out, unless ye want to be sucked under to yer doom.” But when he speaks of the sea, mostly in indirect speech, he takes on the tone of a college lecturer in oceanography, and, after he’s skewered a “huge” fish on his knife and is asked by a passenger whether it is to be eaten raw, Hardie rises to the improbable sarcasm, “No, we’re going to sauté it in a garlic and butter sauce.” Since the various bits of the protean Hardie never really cohere into one, it’s hard for the reader to feel anything much when Grace helps push this paper man into the ocean.

Hardie is sentenced to death not by the traditional marine lottery but in a bizarre show of democracy, when Mrs. Grant calls for a vote (we’re still six years short of universal suffrage for women, achieved with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920). All the men are against Mrs. Grant’s motion; Grace registers her abstention, and the rest of the women, with one ambiguous demurral, vote that Hardie shall die. Grace’s thoughts on the issue:

I whispered, “I abstain. You don’t need my vote. Do whatever you like.” I’m not sure Hardie could hear my words from where he sat, but I shook my head, hoping he would think I had voted no. I still felt some obligation to the man in charge—to men in general—and, of course, to God, who I had always assumed was a man, albeit now I envisioned him in liquid form, capriciously rising up and threatening to drown us, but keeping us alive to endure more of his capriciousness and threats.

Of course we can’t know whether Grace is telling the truth here, but her defense in court rests on demonstrating that this determined woman is weak, indecisive, easily intimidated into submission. Her legal team has dressed her up to look the part (“I alternate between a dove-gray suit and a dark blue dress with a high collar and lace at the cuffs that were purchased for me by my attorneys,”) while Mrs. Grant “presents a fearful sight,” her hair cut short, her “robust” figure squeezed into unflattering black, and Hannah West wears trousers to court. As the modest and pretty young widow, Grace Winter appears to the jury to be an impressionable innocent caught up in a wicked scheme hatched by two older and unattractive lesbians.

But she’s acting, as always; conforming to the rules of the formal game of the trial as it tries to assert jurisdiction over the lawless events in the open boat at sea. The magniloquent language and procedures of the court struggle to contain the mess of degraded humanity aboard Lifeboat 14: “And cannot the killing of Mr. Hardie be seen as the overthrow of a malevolent ruler—a despot, if you will—in that little principality, a tyrannical autocrat who was endangering the lives of the people in his charge?” Grace, closely studying every legal twist and sally, perfectly intuits her own role in the play, and performs it with persuasive conviction. In the survival-of-the-fittest conditions of the courtroom, as of the boat, she demonstrates a Darwinian talent for adaptation, and is sufficiently self-aware to recognize her own role-playing for what it is.

She summons just enough honest regret for the presumed drowning of her banker husband to pass as a grief-stricken widow, even as she keeps her eye on the main chance, determinedly flirting with her lead counsel, Mr. Reichmann, who is now the man of most palpable substance in her life. When she succeeds in leading him on to a proposal, she remarks, “I fear that…I will have to accept Mr. Reichmann’s proposal of marriage for want of a better plan,” and later says:

One couldn’t inhabit the knife-edge cusp of possibility for long without stepping off on one side or the other, as my experiences in the lifeboat had unambiguously shown. Did I get butterflies of happiness in [Reichmann’s] presence? No, but he professed to get them in mine, and it made me happy that he did.

Grace’s cool pragmatism here, as elsewhere in the book, earns the reader’s sympathy, not censure. Acquitted of murder, she shrugs off her last attachments to her fellow defendants, whose death sentences are quickly commuted to life imprisonment. She is for the future; the past—to the exasperation of her psychiatrist—is of minimal interest to her, except that it has liberated her into a new world, “one quite devoid of dependencies on other people, devoid even of the fear of death and belief in God.” It’s the spring of 1915, just after the sinking of the Lusitania, and Grace Winter, “suffused with a sort of happiness” at being set free of the constraints of normal morality, is ready for the century ahead. She will, one assumes, go far.

Partly because the other people in The Lifeboat are drawn so sketchily that they seem little more than bare illustrations to the argument, the novel often sounds offputtingly didactic in tone. It bristles throughout with moral and historical dilemmas that arise from events in the text, and will provide argumentative fodder for book clubs without requiring their members to give the book more than a cursory reading. Charlotte Rogan, whom I take to be in her middling fifties (the only date supplied by her publishers is that she “studied architecture at Princeton University, graduating in 1975,”) will probably write better, more fully fleshed novels than this one, but The Lifeboat is still one hell of a debut.