1.

In January, Min Ko Naing, one of Burma’s leading dissidents, walked out of prison. When the government ordered his release, he was over three years into a sixty-five-year jail term he had received for political activities in support of the “Saffron Revolution,” a nationwide uprising launched against the ruling military junta by Buddhist monks in 2007.

That was not the first time in his life that Min Ko Naing had run afoul of the authorities. He began his career as an activist during another protest movement in 1988 that was brutally suppressed by the reigning generals, who ordered troops to open fire on unarmed demonstrators, killing thousands. Thousands of the survivors disappeared into jails or labor camps, where they endured conditions of unstinting brutality, sometimes for decades. Min Ko Naing survived the crackdown, but as one of the best-known student activists he was squarely in the sights of the government and soon ended up under arrest. Altogether he has spent twenty-one of the past twenty-three years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement.

When I met him a few weeks ago in Rangoon, I was hard-pressed to notice any lingering trauma. A fresh-faced forty-nine-year-old, he greeted me with a firm handshake and a broad smile, then introduced me to his colleague Ko Ko Gyi, a co-leader of the 88 Generation Students Group, a political movement that strives to keep alive the ideals of their youthful revolt. Both men were wearing identical dark longyi, the skirt-like garment that many in Burma (the official name of the country is Myanmar) prefer to trousers, and dazzling white shirts, perhaps an allusion to one of their political campaigns, in which supporters were urged to wear the color white to signal their demand for greater democracy. We sat down in a room in the freshly refurbished building that serves as the headquarters of their movement; the only furniture was a few plastic lawn chairs and an electric fan—no luxury in Burma’s spring dry season, when temperatures regularly hover above a hundred degrees.

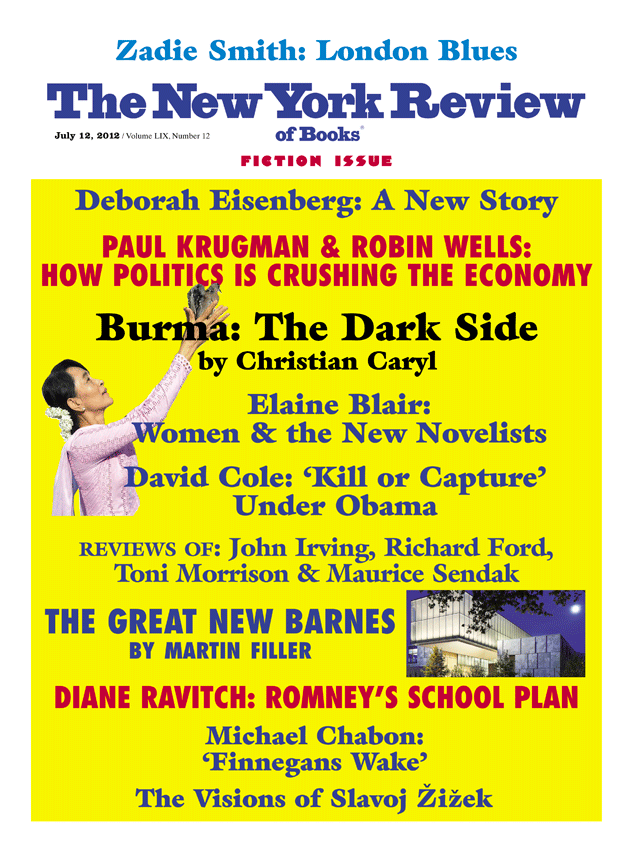

I had come to ask these men what they thought of Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate who only recently emerged from her own latest spell of detention after many dogged years of struggle against the regime, and who is now leading Burma’s pro-democracy movement into a fraught new chapter of anxiety and hope. Last year, after nearly fifty years of military rule, President Thein Sein, himself an ex-general elected to office under constitutional ground rules designed by the old junta, launched a cautious political liberalization. He started ceasefire talks with a number of Burma’s ethnic minority groups, many of them at war with the central government for decades. He suspended a huge dam construction project to be built by the Chinese, thus signaling a reversal of the previous government’s lopsided dependence on assistance from Beijing.

He also loosened censorship rules, allowing for the appearance of new media outlets. He held out the prospect of freedom for Burma’s most prominent political prisoners, a promise that he has since largely fulfilled. Most dramatically of all, he hinted that the government might consider a role in government for Aung San Suu Kyi and her long-banned National League for Democracy (NLD)—an offer he underlined by inviting her to a cordial dinner at his home last August. After the meal, the president made a point of posing for an official photo with her beneath a portrait of her father, Aung San, the storied father of Burma’s postwar independence.

My conversation with the 88 Generation leaders took place just days before the president made good on this overture. On April 1, Burmese in a handful of districts around the country voted in an unprecedented parliamentary by-election. For the first time in decades, the ballots included candidates from the NLD—including Aung San Suu Kyi herself, who ran for a seat in a hardscrabble rural district on the outskirts of Rangoon. (She was released from house arrest in November 2010, shortly after the controversial vote that brought Thein Sein to power.) In their August meeting, Thein Sein had expressly invited Aung San Suu Kyi and her party to participate in the by-election, and after some hesitation the NLD leader accepted the offer, though with considerable misgivings.

The pro-democracy activists had good grounds for caution. The forty-six seats at stake in the election represented a tiny fraction (less than 7 percent) of the overall seats in the national parliament, so even a clean sweep would leave the NLD in a tiny minority, far short of the strength needed to change any laws. On top of that, the military-engineered constitution, crafted by a national assembly widely regarded as a pro-government body, reserves one quarter of the overall seats for members of the armed forces, and otherwise tilts the playing field in favor of the military’s tame party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which commands an overwhelming majority. The most likely opportunity for changing this constitution, if at all, will come no sooner than 2015, when the next national election is scheduled.

Advertisement

The oppositionists thus worried that participation in the by-election might amount to legitimizing a government that they would be in no position to control. When I asked Min Ko Naing about this, he hastened to assure me that Aung San Suu Kyi enjoys the support of his movement, even if the 88 Generation Students Group has carefully remained independent of the NLD. (It was, indeed, Min Ko Naing himself who had an active part in persuading the Lady, as many Burmese respectfully refer to her, to enter national politics for the first time back in 1988.) Even limited involvement in the business of government was better than none, he explained: “She can bring the voice of the people into parliament.”

He then described a government riven between supporters and opponents of Thein Sein’s recent reforms, and stressed that everything should be done to bolster the reformists. “Sixty percent of the government is sitting on the fence,” he said. Above all, he emphasized, this first modest entry into the political system was necessary to assuage the fears of many members of the ruling elite who—all too aware of Aung San Suu Kyi’s immense popularity—know full well the fragility of their own position, and accordingly worry that if they lose control, they could be subject to retribution for the decades of maltreatment the government has meted out to its own citizens.

To underline his point, Min Ko Naing told me a remarkable anecdote. During his most recent stint in a remote provincial prison, he discovered that the inmates included a former army colonel who had an active part in one of his earlier arrests; the ex-officer had landed in jail after losing out in a power struggle in the upper reaches of the regime. Min Ko Naing told me how he had made a point of treating the man with respect rather than enmity. When the officer was released along with the other prisoners in January, journalists approached him for interviews. But he declined, and referred them instead to Min Ko Naing, who, he said, spoke for all the prisoners. “The main emotion I feel for him is pity,” Min Ko Naing told me. “As for me, I have political beliefs. That was why I was in jail. But in his case, a tree fell, and he just happened to be one of the branches.”

I was struck by this story precisely because I had already heard versions of it from other oppositionists. Burma’s pro-democracy activists are confronting a dilemma familiar to many societies that have experienced complicated transitions of their own. In the past, South Africans, Chileans, and Indonesians have all found themselves in comparable positions: the trick is finding acceptable ways to reassure authoritarian power holders that leaving the stage will not expose them or their families to the pent-up demand for vengeance.

These precedents are well known to Burma’s oppositionists; it is such experiences that Aung San Suu Kyi has in mind when she speaks of the need for “restorative” rather than “retributive” justice in a post-authoritarian future. Yet the Burmese approach is not based solely on hardheaded political calculations. Figures like Min Ko Naing share with Aung San Suu Kyi a devotion to Buddhist precepts that deeply informs their striving for democracy and the protection of human rights.1 It is an attitude that attests to a great inner strength. When I asked Min Ko Naing how he felt when he finally emerged from his prison on that January day, his smile never wavered, and he replied without hesitation: “To me, it felt like returning home at the end of a long day’s work.”

I did most of my reporting on the by-election in Independence Ward, a slum district in central Rangoon where a young female social worker by the name of Phyu Phyu Thin was running for the NLD; her main opponent, also a woman, was standing for the pro-government party. NLD campaign rallies in the days leading up to the vote were raucous, joyful affairs. The neighborhood’s very poor residents thronged to each speech the candidate gave. Many of the slum-dwellers wore T-shirts or baseball caps with pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi or her famous father, apparel that often contrasted oddly with the longyi, saris, or hijab worn by the people of the neighborhood, most of them Muslims whose ancestors moved to Burma from Bengal at a time when both places were still part of the British Empire.

Advertisement

Their enthusiasm was evidence that the appeal of the pro-democracy movement reaches beyond the Buddhist Burmese who make up the majority of the country’s citizens. The red banner of the NLD, emblazoned with a white star and a yellow fighting peacock, adorned balconies or dangled from car antennas; the neighborhood kids wore stickers with the emblem on their cheeks or festooned their hats with tiny flags.2 The symbols of the pro-government party, by contrast, were conspicuous by their absence. “We just want things to change,” one man told me. “And Daw Suu3 is the only one who can do it.” When I hazarded that even a clean sweep of the by-election would leave the NLD far from any position of real power in the parliament, my interlocutors dismissed this as hairsplitting. We weren’t talking about just anyone here, they told me; this was Aung San Suu Kyi.

The sense of euphoria was every bit as palpable on election day itself. It soon became apparent that many people in the crowd milling around the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare were election tourists: they had come from districts that weren’t participating in the vote—from hundreds of miles away, in some cases—just to take part in the historic day. The local NLD office put up a chalkboard at the curb that tracked results from the various precincts according to the reports of on-scene election monitors; each figure added to the board prompted a roar of appreciation from the assembled onlookers.

Meanwhile, just across the street, an enormous crowd formed in front of the local polling station. The first official tally wasn’t supposed to be announced for days, but nonetheless each move by the election officials in the shadowy interior of the building met an anticipatory cheer from the people gathered outside. Given the one-sidedness of popular sentiment on display in central Rangoon, it almost seemed anticlimactic when the preliminary results were announced later that night. The pro-democracy movement had won an overwhelming victory. In the days that followed, it became clear that the NLD had won forty-three of the forty-six seats contested.

Burma is a changed country. A little over a year ago, Aung San Suu Kyi was still an unperson; merely mentioning her name was to invite trouble with the authorities. Today she is an officially acknowledged interlocutor of the president and a member of the country’s highest lawmaking body. She and her NLD colleagues took their seats in parliament on May 2. Her image is sold openly by vendors on the streets of Rangoon and newspapers breathlessly report her every move. Indeed, a few days before the April 1 election she invited journalists to a press conference on the lawn of the lakeside home where she has spent most of the past twenty-four years under house arrest; hundreds of us, both Burmese and foreign, showed up, marveling at the faint surrealism of an event that would have been unimaginable not so long before. One of my reporter colleagues recalled his previous trip to Burma early in 2011. He was able to get a visa only by posing as a businessman, and once inside the country resorted to a variety of conspiratorial measures in order to evade the security services and protect the identity of his sources. Now it all seems a bit absurd.

The implications of this shift are potentially as far-reaching as the democratic revolutions of 1989 or the more recent upheavals of the Arab Spring. As Thant Myint-U explains in his excellent political travelogue, Where China Meets India, Burma is a linchpin country in the evolving geopolitics of Asia. It shares borders with both China and India, and policymakers in Beijing and Delhi are feverishly planning ambitious infrastructure projects—pipelines, highways, and railroads—that will allow them to boost their trade between each other as well as with Burma itself, which has an extraordinary wealth of untapped natural resources. Though such plans antedate the current opening, they stand little chance of succeeding unless the Burmese government can find a way to calm the ethnic rebellions in its own borderlands—an aim that is likely to be furthered by liberalization. Meanwhile, an outbreak of democracy in Burma could also have a profound effect on its neighbors in Southeast Asia, where a rising middle class has already begun to challenge long-dominant authoritarian assumptions in some countries.

And yet caution is in order. Despite all the undeniable signs of progress, no one can yet claim that Burma is on an irresistible path to democracy. There are many reasons to be skeptical. It could well be that Thein Sein’s opening is nothing more than a tactical move aimed at getting the Western countries to lift sanctions, thus prolonging the survival of the entrenched elite behind a façade of liberalization. If so, the Burmese president is already well on his way to achieving that end; earlier this month, the Obama administration announced that it was suspending (though not eliminating) several financial sanctions against the regime.

While it makes sense to reward the Burmese government for positive actions, it is also true that the regime still holds all the cards that count. The president and his ministers may have put away their uniforms in accordance with the current constitution’s stipulation that only civilians can hold executive positions, but the reality is that the armed forces continue to exercise virtually unlimited power. In this respect, allowing a few dozen oppositionists into parliament does little to change the basic constellation of forces. Meanwhile, ex-generals or their cronies still control all of the country’s major economic assets.4

Burmese dissidents are quick to point out the limits of the new tolerance. The political prisoners released from jail are not the beneficiaries of an amnesty; under current law, they can be rearrested at any moment for offenses to be defined virtually at the whim of the government. According to Human Rights Watch, hundreds of dissidents remain in prison. Censorship has been merely curtailed, not eliminated. And despite the cease-fires that Thein Sein’s administration has managed to conclude with most of the rebellious ethnic groups, the army actually appears to have stepped up its war against the Kachins in the remote north of the country5—an offensive that has continued despite several cease-and-desist orders from the president.

Some observers speculate that the army’s reluctance to comply has much to do with the fact that the Kachins control access to some of Burma’s most lucrative natural resources; in this reading, the continuation of the conflict is motivated less by patriotic opposition to separatism than the naked greed of the generals in charge. Indeed, it could well be that Burma’s new pseudo-civilian leaders are aiming less for checks-and-balances democracy than a modernized authoritarianism in which they continue to pull the strings—perhaps modeled on the prosperous but despotic nearby states of Malaysia or Singapore. Of course, one can argue that even this option would represent a huge advance for a country whose astonishingly incompetent military rulers have succeeded, in the course of their fifty years at the helm, in reducing one of Asia’s richest countries to one of its poorest.

2.

Even if one is willing to assume that the reformists in the government are sincere in their desire for democratization, the road ahead remains cloudy. What happens next depends to an extraordinary degree on the two central figures. Most of the positive moves made so far can be traced to the personal initiative of President Thein Sein; yet he is an elderly man whose health is clearly not the best. (He suffers from heart disease, and paid a visit to Singapore a few months ago to get his pacemaker replaced.) If he should suddenly vanish from the scene, it is possible that hard-liners will seize the opportunity to reassert themselves. The Burmese system remains opaque and it is extremely hard to assess the strength of the support for Thein Sein’s course within the regime. Few analysts are likely to claim that the president’s reforms are irreversible.

And then there is Aung San Suu Kyi herself. Peter Popham’s vivid new biography, The Lady and the Peacock, illuminates the qualities that have made her one of the twenty-first century’s great political personalities—even though so much of her life as a public figure has been spent in strict isolation from the outside world. There was little to suggest that she was destined for a prominent role in her home country until she was well into her forties. Having married the British academic Michael Aris, with whom she raised two boys, she seemed during her English years little more than a particularly diligent “North Oxford housewife” (a description the Burmese regime would later try to use against her, to little apparent effect).

As Popham shows, though, she was never allowed to forget her unique status as the daughter of modern Burma’s revered founder, and when she returned home in 1988 to tend to her sick mother, events pulled her into the struggle against dictatorship. The leaders of the student uprising pleaded with her to join the pro-democracy cause, and soon enough she was drawing huge crowds to her speeches denouncing the military leaders. In the aftermath of the bloody suppression of the protests, the junta leader resigned, promising new elections. The newly formed NLD duly won them by a landslide.

The generals, apparently jolted by the scale of their defeat, then responded with a new wave of repression. Thousands of activists were rounded up; some were used as pack animals or human mine detectors in the areas where the military continued its fight against ethnic minorities. Aung San Suu Kyi was dispatched into the netherworld of house arrest. The generals refused entry visas to her family while assuring her that she could leave whenever she liked—an offer she resolutely refused, knowing that she would not be allowed to return. She never saw her husband again; Aris died of cancer in 1999. It was only earlier this month, for the first time in twenty-four years, that she felt secure enough to hazard a trip outside of her country. (She went to Thailand, home to millions of Burmese migrant workers trying to escape the poverty of their homeland.)6

The resolve she has displayed along the way is nothing short of astonishing. At one point, during her election campaign in the spring of 1989, she faced a squad of soldiers who aimed their rifles at her and her colleagues. Calmly defying the commanding officer’s orders to vacate the area, she walked straight up to the soldiers and passed through their ranks. As Popham writes:

Word of what had happened and what had so nearly happened helped to consolidate Suu’s reputation among the deeply superstitious Burmese public, many of whom now began to consider her a female bodhisattva, an angel, a divine being. The fact that she had survived the army’s attempt to kill her was proof positive of her high spiritual attainment: only someone “invulnerable to attack,” “guarded by deities” and “subject to adoration” could have come through alive…. In January Suu had told the New York Times reporter, “I don’t want a personality cult; we’ve had enough dictators already.” But it didn’t really matter whether she wanted it or not. Now she would be stuck with it, forever.

Popham, refreshingly, does not treat his protagonist like the “democracy icon” of lazy journalistic copy. In his portrayal, she is at once deeply traditional and effortlessly cosmopolitan, whimsically witty and ferociously short-tempered. (In one revealing aside, Popham tells us that she and her husband had to give up playing Monopoly because of the fights that erupted during the game.) A friend from her school days in New Delhi in the early 1960s describes the reigning atmosphere at the time as “post-colonial Victorian,” and this seems to have left as much of an imprint as the traditional Buddhist values of her upbringing; adjectives like “prim,” “puritanical,” and “unbending” stud the biography at regular intervals. It is, of course, the resulting sense of “firmly rooted…moral certainties” (to use Popham’s words) that best explains her unstinting resistance to an equally uncompromising dictatorship. When one reporter at her pre-election press conference in Rangoon asked her about the legacy she hopes to leave to posterity, she answered simply: “I want to be remembered as someone who did her duty.” Gladstone could not have said it better.

This has certain implications for the road ahead. As Popham notes, Aung San Suu Kyi’s struggle against the government at the end of the 1980s was characterized by a steely refusal to entertain the possibility of any compromise with a morally tainted regime. Today, it is precisely the path of compromise—messy, opaque, and morally fraught—that she has chosen to travel. The choices ahead will be tough, and they are likely to involve more pragmatism than principle. (Indeed, the NLD’s entry into parliament was briefly marred by the activists’ idealistic refusal to take an oath to the current constitution—a point they were soon forced to concede.) At the end of Popham’s book, Gene Sharp, the famous theoretician of nonviolent regime change, trenchantly observes that Aung San Suu Kyi “is not a strategist, she is a moral leader. That is not sufficient to plan a strategy.”

He may well be right. But this story is a long way from over. At age sixty-six, the post-Victorian bodhisattva now embarks on an entirely different form of political struggle. It is certain to be a tricky one, both for her and for the country at large.

-

1

It is worth noting, of course, that Burma’s rulers, distinguished by their stunningly vicious treatment of their own citizens over the past few decades, also claim to be pious Buddhists. ↩

-

2

It remains to be seen whether this positive view of the pro-democracy movement will survive the outburst of ethnic tension in Rakhine State on the border with Bangladesh, where recent clashes between Buddhists and Muslims prompted Thein Sein to declare a state of emergency on June 10. See Gwen Robinson, “Sectarian Tension ‘Threat to Myanmar Transition,’” Financial Times, June 10, 2012. ↩

-

3

Daw is an honorific word, often used by Burmese when referring to Aung San Suu Kyi. ↩

-

4

See “The Road Up from Mandalay,” The Economist, April 21, 2012. ↩

-

5

See Sebastian Strangio, “How the Optimism About Burma Is Subverted by Its Never-Ending Civil War,” The New Republic, May 23, 2012. ↩

-

6

See the Financial Times report on the possible repercussions of her recent travels: Gwen Robinson, “Suu Kyi Celebrity Status Hits Reform Efforts,” Financial Times, June 10, 2012. ↩