The show of Renaissance portraits now on view in New York is of staggering beauty and revelatory importance. Bringing together nearly 150 masterpieces of fifteenth-century Italian art, it is the richest examination ever presented of the portrait during the first stages of its development in Europe following the end of the Middle Ages. It is a landmark exhibition, one that seeks both to affirm and to revise a common belief about the Renaissance: that it was a time of unprecedented ascent in the power, the freedom, and the self-understanding of the individual.

The organizers of “The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini” have taken the unusual step of limiting their study to Italy in the fifteenth century. Most earlier books and shows on Renaissance portraiture include art from other countries, especially Flanders and Germany, and from the sixteenth century. That is a natural choice, given the crucial importance of Jan van Eyck, Hans Holbein, Albrecht Dürer, Titian, and many others in the evolution of the portrait. But as the foreword to the show’s catalog states, the curators felt that

the special character of portraiture in this early phase is best understood if examined in the context of its own time…. The fifteenth-century portrait was shaped by ideals and social conventions distinct from those of subsequent centuries and far removed from those of our own.

One major goal of the show is to replace a generalized notion of the Renaissance portrait with a more nuanced, complex, and historically grounded understanding.

By looking in such a concentrated fashion, the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art demonstrates that there was not one type or ideal of the Renaissance portrait, but many. It is a series of mini-exhibitions, each on portraiture from a different region. It opens with four rooms dedicated to the portrait in Florence, continues with two rooms of works made for the princely courts, especially those of Ferrara, Milan, and Naples, and concludes with two rooms of images from Venice and the Veneto. This organization reveals the widely varied character of portraits from these different places. Walking from one section to another, the visitor encounters dramatic shifts in the scale and medium of the works of art; most importantly, the mode of presentation of the men and women changes, so that some images are forbidding and remote, whereas others are of startling immediacy.

The show reaffirms the thesis, first presented in 1860 by Jacob Burckhardt in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, that one of the dominant characteristics of the epoch was “The Development of the Individual”—to use the title of a section of the book. Burckhardt famously said:

Man [previously] was conscious of himself only as member of a race, people, party, family, or corporation—only through some general category. In Italy this veil first melted into air; an objective treatment and consideration of the state and of all things of this world became possible. The subjective side at the same time asserted itself with corresponding emphasis; man became a spiritual individual, and recognized himself as such.

Burckhardt’s idea has had the most profound influence on the study of the Renaissance portrait, beginning with his own masterly essay on the subject, published in 1898, and continuing up to the present day. For instance, John Pope-Hennessy’s The Portrait in the Renaissance (1966), a standard reference, opens with a chapter called “The Cult of Personality,” and Nicholas Mann and Luke Syson’s more recent book on the topic is titled The Image of the Individual (1998).

Viewing the show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one cannot help but be struck by the vitality, distinctiveness, and particularity of the men and women portrayed. They gaze at you and beckon to you, clamoring for your attention, like the shades of the dead calling to Odysseus during his visit to Hades, or the figures speaking to Dante in The Divine Comedy. Such urgent declarations of self and calls for recognition are unlike anything that had come before in European visual art, even in the classical era. The soundness of Burckhardt’s insight seems certain.

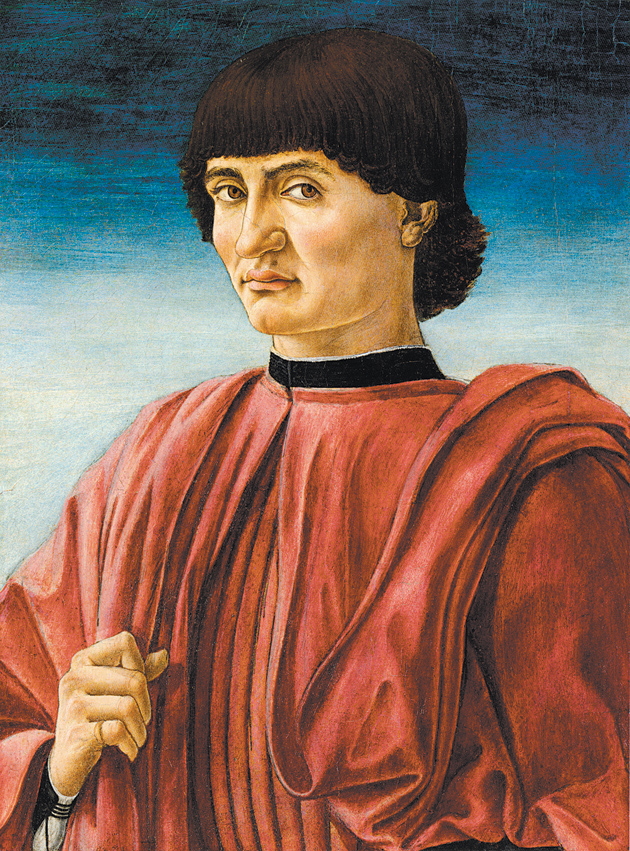

At the same time, however, the show offers a corrective to this idea. In Burckhardt’s formulation, the individual was seen in distinction from the group. But in the exhibition what we often view are individuals portrayed as the preeminent and exemplary representatives of groups; the men and women are depicted as distinguished members of a virtuous and honored elite. This is perhaps most evident in the room of Florentine male portraits: almost all the men there are shown dressed exactly alike in the distinctive red tunics that identified them as citizens of Florence. The city’s government was a republic, not a democracy, and only a small group of patricians was legally enfranchised. Their costume thus is a badge of honor that marks them as men of learning, wealth, achievement, and consequence.

Advertisement

In the modern era, we sometimes believe portraiture should reveal an inner self of thought and feeling. By contrast, in much of fifteenth-century Italy, portraits chiefly presented a public identity, not a private one. To be sure these paintings and sculptures are images of character. But virtue and character were routinely understood to be familial, social, and political, not lyrical or psychological. At the entrance of the show, the curators announce:

The goal [of portraiture] was to confer a distinct identity on a subject—as a husband or wife, merchant or intellectual, military commander, civic office holder or prince.

Portraiture was a matter of both description and aspiration; it sought to capture the likeness of a particular man or woman and simultaneously to suggest how that person exemplified a type or ideal.

In their concentration on the fifteenth century, the show and catalog say little about the precedents that helped lead to the efflorescence of portraiture in this time. For much of the Middle Ages, only the most highly honored persons, especially Christ, saints, rulers, and popes, were celebrated in art. Portraits of other figures were exceedingly rare. There was also comparatively little concern for capturing the distinctive features of an individual’s face. To be sure, an image of Christ, a saint, or a ruler was meant to be a vera effigies—a true likeness. But while there are some exceptions, such as the sculptures of Ekkehard and Uta in the cathedral of Naumberg from around 1249, most portraits lacked recognizable particularity.

Beginning in the late thirteenth century several changes greatly stimulated the advance of portraiture. One was the ascent of the Franciscan and Dominican orders. The personal charisma of the leaders of these movements was considered crucial for their followers’ sense of mission, and to this end images of Saint Francis, Saint Dominic, and other distinguished members of the orders were created in great numbers. These figures, moreover, were routinely portrayed with much credible detail. For example, the fresco cycle of Albert the Great and other Dominican scholars, painted in Treviso in 1352 by Tommaso of Modena, represents each man in a fully individualized way, while also conveying their shared passion for study and the pursuit of truth. The importance of portraiture in these orders continued throughout the Renaissance; in the exhibition it can be seen in Jacopo Bellini’s portrait of the Franciscan preacher Bernardino of Siena and Giovanni Bellini’s portrait of the Dominican Fra Teodoro of Urbino.

Another major development in the fourteenth century was the great increase in both the building of churches and chapels and the commissioning of altarpieces to decorate them. In these settings, for the first time it was deemed permissible for a convincing likeness of a donor to be shown, even if he was a nonroyal layperson. One extremely important early instance is Giotto’s fresco of Enrico Scrovegni in the Arena Chapel in Padua from about 1305. The popularity of donor portraits grew through the century, and appears to have accelerated following the devastating epidemics of the Black Death in 1348 and again in the 1360s.

From the time of Giotto, furthermore, it became acceptable to include portraits of artists, poets, politicians, soldiers, and other prominent figures in group scenes in narrative frescoes, even of religious subjects. Although these figures were almost never identified by name, their presence added to the image’s credibility. Perhaps the most famous example of this practice was the now lost fresco by Masaccio, made in the 1420s, showing the consecration of the church of Carmine in Florence. According to Vasari, the painter included portraits of Brunelleschi, Donatello, Masolino, and many others among the men in the crowd.

There was one other important form of portraiture in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries: fresco cycles of biblical and classical heroes and other illustrious men. Nearly all these series have been destroyed, and we have few documents or descriptions, but we know that they included many prestigious works, including frescoes by Giotto in the Palazzo Reale in Naples, paintings by one of his followers in the Orsini Palace in Rome, and a late-fourteenth-century cycle in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. One of the few surviving instances is Andrea del Castagno’s frescoes of famous men, which he painted for the Villa Carducci, outside of Florence, around 1450.

So portraits had existed before, but it was only in the fifteenth century that independent images of actual persons other than rulers and religious figures began to be made in large numbers. This new tendency started in Flanders, and then spread to Florence, where it reached unprecedented currency. The Florentine portraits represent the patricians of the city and their families—their wives, sons, and daughters. One room of the show concentrates on portraits of women, and some of these sculptures and paintings, such as Botticelli’s two ravishing images of the celebrated beauty Simonetta Vespucci, shown with her golden hair fluttering around her head as if blown by the wind, are surely poetic fantasies.

Advertisement

Many of these images, however, seem to aim for a large measure of frankness in their presentation. The women are elegantly yet plainly dressed, with little ornament or jewelry, and their expressions convey both modesty and self-esteem. In the Florentine treatises of the time on civil life, the word onestà can have connotations of both honesty and honor, and many of the paintings and sculptures appear to seek this balance of values.

Almost all Florentine portraits were intended for display in a family house. Typically they were meant to celebrate the worthy members of the clan and to inspire the young to live up to the standards set by their ancestors; they also gave proof that a family was one of renown and dignity. We can be certain that portraiture served these uses, because of a remarkable dialogue written in 1440 by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini. On Nobility is, I believe, the first post-classical text to comment at some length on the portrait. One interlocutor in the dialogue states:

Illustrious men of old used to ornament their homes…with statues, paintings, and busts of their ancestors to glorify their own name and their lineage…. They adorned their libraries and gardens with art in order to ennoble those places and show their own good taste and well-spent efforts. For they believed that the images of men who had excelled in the pursuit of glory and wisdom, if placed before the eyes, would help ennoble and stir up the soul….

The honor of our fathers is like a light illuminating us and making us more worthy and notable. Who would really deny that the virtues of our ancestors make us nobler and more illustrious? If we want our own deeds to be praised and remembered by our posterity, the recollection and praise of parents must shine—as their portraits would—on sons.

Bracciolini was close to the circle of men who helped popularize the making of portraits in Florence. He was a friend of Donatello, whose extraordinary gilt-bronze bust of Saint Rossore is the first work in the exhibition. He was also a friend of the Medici. Indeed, the man who speaks these words in the dialogue is Lorenzo de’ Medici—the brother of Cosimo the Elder and the namesake of the more famous Lorenzo the Magnificent later in the fifteenth century, both of whom are portrayed in the show; this man was also the uncle of Piero de’ Medici, whose extraordinary bust animates and commands the third room of the exhibition.

The astonishing sculpture of Piero was carved in 1453–1454 by the Florentine sculptor Mino da Fiesole, and as Francesco Caglioti writes in the catalog, it is “the oldest authenticated example we have of a post-classical portrait of a living person in the form of a marble bust.” The artist and patrons of the sculpture surely looked to antiquity for inspiration in making this work, and yet in the presentation of character it is fundamentally different from a classical statue of a Roman emperor or noble. With alert and lively intelligence, Piero seems to turn his head to gaze at you as you enter the room, and his expression is calm, open, and almost inviting, rather than haughty and domineering. This is not a ruler portrait—it was made when the Medici were still no more than citizens, although they were then consolidating their grip on the city. Yet it presents Piero as a new kind of man and leader, one whose claim on our respect comes not from his status or office, but from his foresight and charisma. The portrait suggests that it is by natural ability that Piero ranks as primus inter pares—first among equals.

Many of the other portraits of Florentine men in the show share this emphasis on intelligence, energy, and talent. The figures look shrewd, alert, and ready to judge and respond to risk or opportunity. For example, in Andrea del Castagno’s Portrait of a Man from about 1450–1457, the young man stands in a lively pose—he tugs on his cloak with his right hand, creating a strong sense of potential movement—and he glares out of the picture with a fierce and skeptical expression. He seems knowing, watchful, and vigilant. Rarely before, and nowhere else in Italy in this era, did portraits seek to convey such characteristics. Images of rulers typically celebrated their august power or merciful justice, while portraits of poets and philosophers illustrated wisdom. The male figures in these rooms seem to possess the more worldly qualities of hardy resolve and penetrating discernment.

Florentines in this era believed that while family heritage and the right measure of elegance added to dignity, true nobility had to be earned over and over again by ceaseless striving and success. For instance, Bracciolini said:

While the Greeks consider nobility derived from birth, we call men noble for their own upright deeds and for the glory and fame they win by their own character. We seem to derive the word from ourselves (nobismet ipsis), not from others. We think a man ennobled by some great deed that brings both wide renown and high esteem.

Life was a contest and struggle, but it permitted—and demanded—the display of virtue and the acquisition of fame. The Florentine architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti, whose small bronze self-portrait relief is on view in the show, was expressing a common sentiment when he wrote, “Virtue has its own great reward: it makes itself praised…. Let us try with all our might and skill to acquire praise and reputation.” The portraits of these men proclaim their capacity to prove worthy to the challenge.

The thirst for glory is also clear in the portraits on view from the princely courts. Although widely spread through Italy from Milan to Naples, these cities form a common group because of their similarities in political structure and patronage of the arts; their ruling families, moreover, were closely bound by intermarriage and alliance. Nearly all the lords of these cities were military despots who served as condottieri—generals of private mercenary armies; and they used the immense profits they won at war to buy grand aristocratic titles, such as marquis and duke, from the pope and Holy Roman Emperor.

According to Burckhardt’s unforgettable analysis of these men, their need for fame and their fear of political illegitimacy were thoroughly entwined. The right to rule was believed to be of divine origin. But many of these families had seized power by overthrowing a previous head of state, and there was doubt that the high rank they bought at great cost from the pope or emperor gave them the legitimacy they hoped for. Moreover, there were no laws for succession—what counted was ability, not birth order—and ruling families were plagued by endless struggles for power. Each despot had to prove to everyone, perhaps especially his own murderously jealous relatives, that he was superior in strength and entitled to rule. It was a ruthless way of life, where any mistake could be punished by death. Burckhardt wrote:

The dangers to which these princes were constantly exposed developed in them capacities of a remarkable kind…. Only a man of consummate address could hope to succeed.

To be sure, they were magnanimous patrons of the arts and learning—the Gonzaga in Mantua founded the first humanist school of the Renaissance, and King Alfonso of Naples created one of the first literary academies in Europe. But they were also amoral, tyrannical, and full of what Burckhardt called “cruel egoism.”

The portraits they commissioned are strikingly different from those made in Florence. These princely images tend to be smaller in scale and more jewel-like. Indeed, the show includes a portrait medallion of Alfonso of Naples in gilt bronze, as well as a small round relief of Isabella d’Este in solid gold, with her name spelled out in diamonds. The figures in princely portraits are also much more sumptuously dressed than the Florentines; their tunics are of rich damask, and the women, and sometimes even the men, are shown displaying jewelry. Moreover, they do not look you in the eye, equal to equal, as the men and women in so many Florentine pictures do. Instead, most of these images illustrate the person in profile, like classical coins of a Roman emperor. The biggest difference of all is in the highly restricted patronage of these images. In Florence many patricians commissioned likenesses; in the cities controlled by despots, only the ruling families regularly had portraits made.

The liveliest and most alluring images in this section are the medals. Revived as a genre of art by Pisanello around 1440, the portrait medal quickly became fashionable among the princely families. These works are small and in very low relief, almost like miniatures in bronze, and they are miracles of concision. Working with a bare minimum of essential features, such as the outline of the face and the relation of the masses of the head and chest, Pisanello was able to suggest the ideal characteristics of the portrayed. The reverses of the medals too, decorated with imaginative allegorical scenes, have extraordinary charm. The Duke of Ferrara Leonello d’Este was not a handsome man, but in a medal cast to celebrate his wedding Pisanello was able to endow his prognathous features with a sense of moral force; and the reverse, showing a cupid teaching a lion (leone in Italian) to sing an air of love, is one of the great poetic images of the fifteenth century. Looking at medals such as these, it is easy to understand why a courtier wrote to Filippo Maria Visconti, lord of Milan, “Those who wish never to be forgotten by the world, come and be portrayed from life by my Pisanello.”

Minted in relatively large numbers, medals were especially useful in the spread of one’s fame. Patrons would give these images of themselves to their friends, relatives, and attendants; and they also buried them in the foundations of the buildings they commissioned. They did this, the fifteenth-century architect Filarete said, so that future generations would “remember us and know our names, just as we remember them [our forebears] when we find some noble things in an excavation or ruin.”

In the final rooms of the exhibition, dedicated to the portraiture of Venice and the Veneto, the visitor encounters an entirely different sensibility. Whereas the other portraits in the show typically stress achievement and fame, these images are more intimate in character. Many of these pictures are framed quite tightly so that the focus is on the face, rather than the head and torso. There is also a fundamental difference in the fall of light. The illumination in Florentine and court portraiture tends to be flat and even. But in Venetian portraits light is shown slanting across the face and sparkling in the eyes, giving a sense of mood and animation. There is a greater air of immediacy, spontaneity, and privacy; the personal temperament, not just the public self, of the person portrayed seems to be on view.

The range of characterization in these pictures is also extraordinary. For instance, the stern figure in Andrea Mantegna’s Cardinal Ludovico Trevisan appears about to growl, while the charming youth in Antonello da Messina’s Portrait of a Young Man has just started to smile. This emphasis on expression has few parallels in the portraiture from other regions of fifteenth-century Italy.

One reason for the greater intimacy of northern Italian portraiture is the response of artists and patrons there to contemporary Flemish painters, such as Petrus Christus and Hans Memling, whose works were then being imported into Italy in large numbers. Portraits in Flanders were often made as part of small diptychs or triptychs, and showed the figure in a moment of private prayer to the Virgin and Child; such images had a strongly meditative bearing. In Florence and the courts such characterization of a subject was seen to be largely irrelevant to the social functions of portraiture. In Venice and the Veneto, on the other hand, Flemish painting’s tone of religious devotion was taken as the perfect model for creating an impression of poetic soulfulness.

The patronage of portraiture had a broader social base in Venice than anywhere else in Italy. Some of the men and women depicted in this section are persons of the highest status, such as a doge, a senator, and a queen. But the dress of many of the people on display gives little indication of their rank, and among the figures depicted are a friar, a scholar, and a humanist. Venice was La Serenissima—a stable republic, where overt social competition was strongly discouraged as dangerous to the political order. Since portraiture could not serve self-promotion—at least not to the same degree as elsewhere in Europe—it came to explore other ends and uses.

The last work in the exhibition exemplifies these changes. Painted in 1515, about fifteen years later than any other work in the show, it is Giovanni Bellini’s portrait of Fra Teodoro da Urbino, a Dominican friar and possibly the artist’s spiritual adviser. This extraordinarily powerful picture represents Teodoro holding a book and a lily, the symbols associated with Saint Dominic, the founder of his order, and it is surely meant to convey Teodoro’s emulation of the saint. A painting of astonishing empathy, it shows an elderly man, near the end of his earthly existence, gazing into the future and contemplating both death and life. His face shines from the light streaming across it, and his eyes are aglow with wisdom, intelligence, and benevolence. Despite its somewhat abraded condition, it is a deeply moving work.

The show opens with a gilt-bronze statue of a miracle-working saint. It continues with images of men and women seeking to be and to appear to be virtuous, exemplary, and powerful. It concludes with images that reveal a range of emotion and depth of feeling never before shown in European portraiture. This magnificent exhibition conveys the variety and abundance of early Italian Renaissance portraiture, and also suggests some of the reasons it proved so fundamental for the visual imagination of the sixteenth century and later Western art, even up to the twentieth century. It is a good question how Renaissance portraiture will be seen in the years ahead.

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

Why Not Frack?