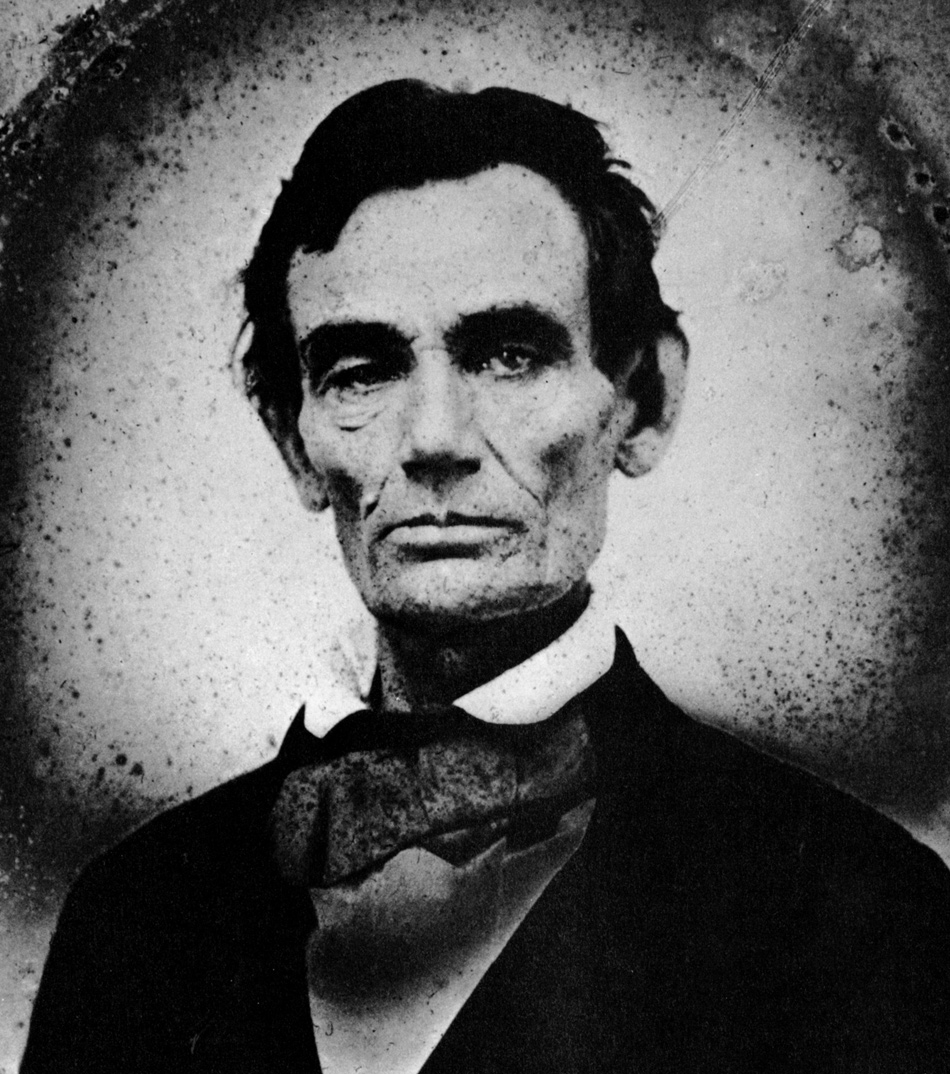

In a Thanksgiving sermon in 1862 at the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, the prominent clergyman Reverend Albert Barnes reflected on the momentous events of that second year of the Civil War. “It has been such a year as our country has never experienced before,” he said, “and will make more work for the calm and impartial historian of future times, than any one year in all our public history.” The four historians whose books are reviewed here have written about 1862 in a manner that is perhaps neither entirely calm nor impartial, but quite suitable to the tumultuous atmosphere of wartime crisis that pervaded the era. All four point toward the climax on the first day of 1863, when Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, one of those “great national acts,” in the words of the black leader Frederick Douglass in a speech that year,

which by their relation to universal principles, properly belong to the whole human family…. Henceforth that day shall take rank with the Fourth of July. [Applause.] Henceforth it becomes the date of a new and glorious era in the history of American liberty.

When Lincoln published a preliminary proclamation on September 22, 1862, warning Confederate states of his intention to issue a final edict on January 1, he did not realize that those two dates stood precisely one hundred days apart. Louis Masur’s Lincoln’s Hundred Days focuses on that crucial period, but it starts more than a year earlier to set the stage for those hundred days, and follows up with the aftermath and consequences of Lincoln’s historic action. Masur and Harold Holzer argue persuasively that the progression of events during that critical autumn of the war were full of contingencies and that the final outcome was by no means certain.

Seven Southern states had seceded in 1861 because they feared the incoming Lincoln’s administration’s designs on slavery. In a vain effort to stem further secessions and bring back the states that had gone out, Lincoln declared that he had no intention or power to interfere with slavery in the states, but only to restrict its further expansion. Southerners were not reassured. When the war began with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, four more states seceded. Many members of Lincoln’s own Republican Party urged him to strike against slavery. The slaves provided much of the labor that sustained the Southern economy and the logistics of Confederate armies. From almost the first days of the war, slaves began coming into Union lines wherever Northern armies and naval vessels penetrated the South. By the fall of 1861, tens of thousands of them had gained sanctuary and a practical if not yet legal freedom. Their labor was lost to the Confederacy and gained by the Union.

Abolitionists, black leaders, and radical Republicans pressed Lincoln to ratify and expand this process by using his war powers as commander in chief to seize enemy property—slaves—being used to wage war against the United States. But Lincoln hesitated to embrace such a sweeping policy. He was trying to hold together a precarious war coalition of Northern Democrats and Unionists from the border slave states that had not seceded (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware) as well as Republicans. He was concerned—with good reason—that the first two parts of that coalition might break away if he took the kind of bold action the radicals wanted.

When General John C. Frémont issued an order freeing the slaves of Confederates in the border state of Missouri in August 1861, Lincoln revoked it. To a friend who protested this revocation, Lincoln explained that if he had let Fremont’s edict stand, Kentucky would have seceded. “Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.”1

Apart from these practical consequences, wrote Lincoln, neither Fremont nor the president himself had the constitutional authority to order the freeing of slaves. “Can it be pretended,” he wrote, “that it is any longer the government of the US—any government of constitution and laws,—wherein a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation?” Masur notes the irony of the date of this letter: September 22, 1861, one year to the day before Lincoln issued his proclamation stating an intention to do precisely what he had said a president could not do. “Lincoln had much intellectual work ahead of him,” writes Masur; “events would help to take him there.”

All four of these books provide detailed and careful renderings of these events and of Lincoln’s intellectual journey. In August 1861, Congress in effect freed slaves who had worked in any capacity for Southern armies and who subsequently came within Union lines. The secretary of the navy ordered ship captains to accept all slaves (called “contrabands”) who sought asylum and to recruit able-bodied young males into the navy. In March 1862 Congress prohibited the army from returning to their owners any slaves who came into Union lines. The following month Congress abolished slavery in the District of Columbia, and in July 1862 passed a second act that “confiscated” the slaves and declared free all slaves of owners who could be proved to have supported the Confederacy.

Advertisement

Lincoln signed all of this legislation. He also tried to persuade representatives from the Union border states to accept a plan for gradual abolition of slavery in them, with compensation from the federal government. They refused, and that refusal moved Lincoln toward a decision to issue an emancipation proclamation. Confederate military counteroffensives in the summer of 1862 culminating in the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August reversed the momentum of Union victories earlier in the year, undercutting the hope that the war would soon be won without resorting to radical measures. Lincoln had grown disillusioned with Southern Unionists, such as Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and Thomas J. Durant of Louisiana, whom he had previously tried to conciliate. He declared that he could no longer fight this war “with elder-stalk squirts, charged with rose water.” The government

cannot much longer play a game in which it stakes all, and its enemies stake nothing. Those enemies must understand that they cannot experiment for ten years trying to destroy the government, and if they fail still come back into the Union unhurt.

The demand by supposed Southern Unionists “that the government shall not strike its open enemies, lest they be struck by accident” had become “the paralysis—the dead palsy—of the government in this whole struggle.”2

Lincoln had overcome his earlier doubts about the constitutionality of a president making “permanent rules of property.” He was impressed by the arguments of William Whiting, a prominent New England lawyer and solicitor of the War Department, whose pamphlet The War Powers of the President, and the Legislative Powers of Congress in Relation to Rebellion, Treason and Slavery went through seven editions in little more than a year. Whiting maintained that the laws of war “give the President full belligerent rights” as commander in chief to seize enemy property, including slaves. “This right of seizure and condemnation is harsh,” wrote Whiting, “as all the proceedings of war are harsh, in the extreme, but is nevertheless lawful.” And once the slaves were “seized,” the government would surely never allow them to be reenslaved.3

As the war took a turn for the worse in the summer of 1862, Lincoln now fully embraced the idea that as commander in chief he could proclaim emancipation as a means of weakening the enemy. During a carriage ride on July 13, 1862, to attend the funeral of the infant son of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the president startled his seatmates William H. Seward and Gideon Welles, the secretaries of state and the navy. He told them that he had made up his mind to issue the proclamation. As Welles later reported the conversation, Lincoln said that emancipation had become “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.” The bondsmen were “undeniably an element of strength to those who had their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.” Lincoln brushed aside any question of the constitutionality of such action.

“The rebels,” he said, “could not at the same time throw off the Constitution and invoke its aid. Having made war upon the Government, they were subject to the incidents and calamities of war.” The border states, Lincoln now acknowledged, “would do nothing” on their own; indeed, perhaps after all it was not fair to ask them to give up slavery while Confederates retained it. Therefore “the blow must fall first and foremost” on Confederates. “Decisive and extreme measures must be adopted…. We [want] the army to strike more vigorous blows. The Administration must set the army an example, and strike at the heart of the rebellion”—slavery.4

Nine days later, on July 22, Lincoln informed the full Cabinet of his intention. After some discussion of details, Seward advised that the proclamation be withheld during this period of defeatism in the North over Union reverses in the Seven Days Battles in Virginia some three weeks earlier. To issue it now might give the appearance—especially abroad—of an act of desperation, an appeal for a slave insurrection, “our last shriek on the retreat.” Wait until you can make it public backed by military success, counseled Seward. Lincoln accepted this advice and tried to turn the delay to his advantage. As Harold Holzer describes, he began to expand the circle of Washington insiders who knew his plan during this time. Meanwhile, he put the proclamation away and waited for a victory.

Advertisement

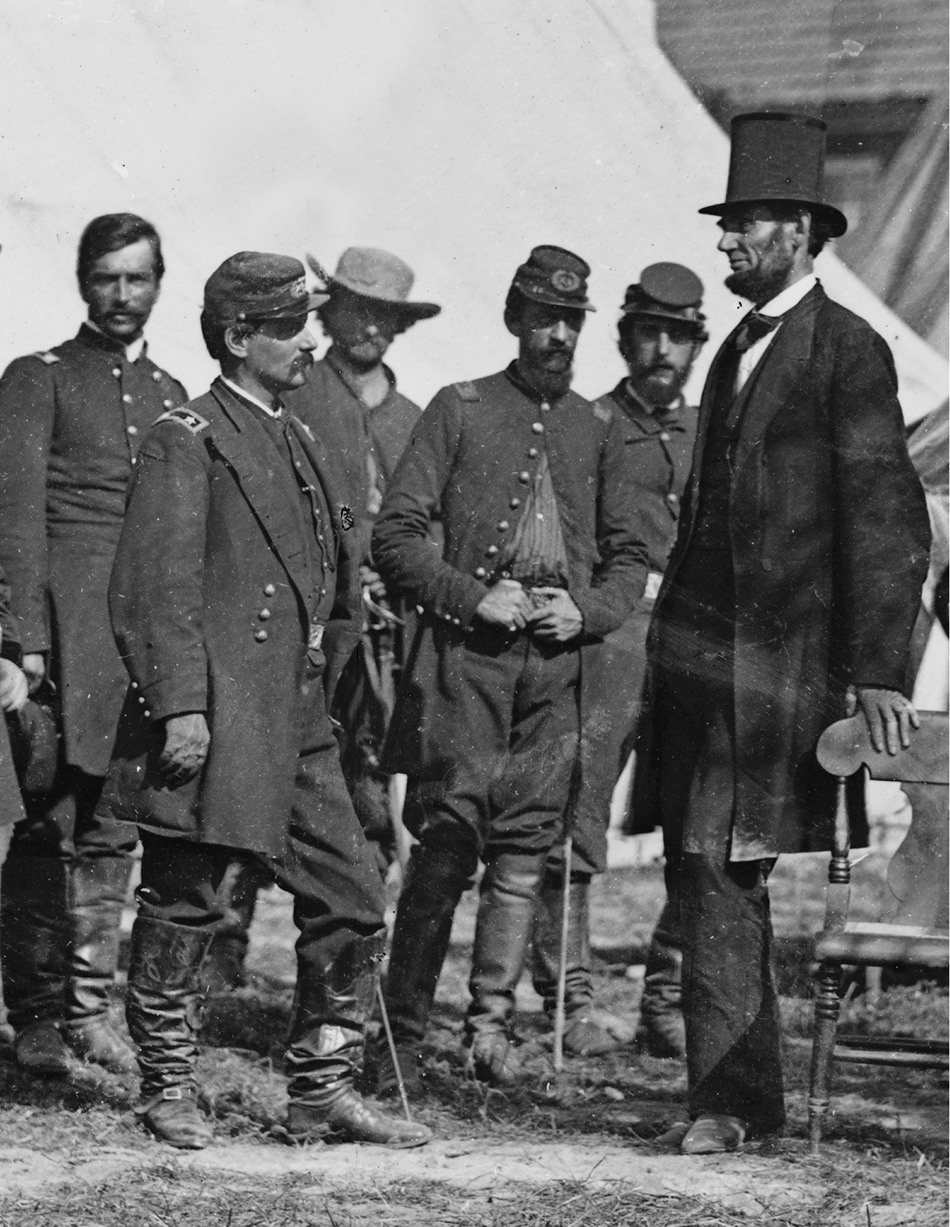

It proved to be a long, agonizing wait, but the success of the Army of the Potomac in turning back the Army of Northern Virginia at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, was the victory Lincoln had waited for. Five days later he called a special meeting of the Cabinet. “I think the time has come now,” he told them. “I wish it were a better time…. The action of the army against the rebels has not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland.” When the enemy was at Frederick, Maryland, Lincoln had made a “promise to myself, and…to my Maker” that “if God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, [I] would consider it an indication of Divine will” in favor of emancipation. Antietam was God’s sign that he “had decided this question in favor of the slaves.” Thus he intended to issue that day the proclamation warning Confederate states that unless they returned to the Union by January 1, 1863, their slaves “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”5

As Harold Holzer points out, there had been plenty of hints that something like this was forthcoming. Nevertheless, the proclamation landed like a bombshell on the American public. Republicans praised it, Democrats denounced it, some officers and soldiers in the Union army welcomed it, others including General George B. McClellan privately condemned it, many in the border states reprehended it, Southern whites ridiculed it, and blacks both free and slave thanked God and Abraham Lincoln for this righteous decree.

After Antietam, in September 1862, and the battle of Perryville in Kentucky the following month, which forced a Confederate army to retreat from that state, Union fortunes again took a turn for the worse. Democrats made gains in the fall elections of 1862, though the Republicans retained control of Congress. Instead of strengthening the Union cause abroad, as Lincoln had expected, the preliminary proclamation actually seemed to harm it, as Seward had feared. One clause in the edict gave critics, especially in Britain, an opportunity to misrepresent the document as an incitement to slave insurrection. The army and navy, said Lincoln, “will do no act or acts to repress [slaves] in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.”

Lincoln meant only that the US army should not turn escaping slaves away from Union lines. But Southerners, Democrats, and the Times of London among other foreign newspapers jumped on these words and branded Lincoln another John Brown. With this proclamation, declared the Times, Lincoln

will appeal to the black blood of the African; he will whisper of the pleasures of spoil and of the gratification of yet fiercer instincts; and when the blood begins to flow and shrieks come piercing through the darkness, Mr. LINCOLN will wait till the rising flames tell that all is consummated, and then he will rub his hands and think that revenge is sweet.6

In December 1862 the disastrous Union defeat at Fredericksburg, in Virginia, was followed by a Cabinet crisis in which Republican senators tried to force Lincoln to get rid of Seward as secretary of state and reorganize his Cabinet. Combined with Democratic gains in the elections, these events “ignited rumors that Lincoln would in fact blink and let the January 1 deadline pass without signing the order at all,” according to Holzer. His wife, Mary Lincoln, urged him not to sign. But Lincoln’s closest associates were confident that he would not back down. A New York Republican commented that “every conceivable influence has been brought to bear on him to influence him to withhold or modify—threats, entreaties, all sorts of humbugs, but he is as firm as a mule.” And so he was. On New Year’s Day, after shaking hands for three hours at the annual White House reception, Lincoln retired to his office and signed the historic document. “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act,” he declared, “and my whole soul is in it.”

The final proclamation exempted from emancipation the border states and some parts of Confederate states controlled by Union forces. They were deemed not to be at war with the United States; therefore the president’s power as commander in chief to seize enemy property could not apply to them. These exemptions gave rise to the accusation that Lincoln “freed” the slaves in areas where he had no power, and left them in slavery where he did have power.

Nothing could be more wrong. For one thing, tens of thousands of ex-slaves lived in parts of the Confederacy that were occupied by Union forces but were not exempted from the proclamation. They celebrated it as their charter of freedom. For that matter, so did many slaves in exempted areas, which included the four slave-holding states that never left the Union (Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware, and Maryland) as well as Confederate areas that had been returned to Union control, such as New Orleans and the forty-eight Virginia counties that would soon become West Virginia. They recognized that if emancipation took hold in the Confederate states, slavery could scarcely survive in the upper South.

The proclamation officially turned the Union army into an army of liberation—if it could win the war. And by authorizing the enlistment of freed slaves in the army, the final proclamation went a long step toward creating that army of liberation. If the Emancipation Proclamation was merely a piece of paper that did not actually free anyone, as skeptics then and later charged, the Declaration of Independence was likewise a mere piece of paper that did not in itself create a new nation. Both outcomes depended on victory in a war to which these documents gave new purpose.

To mollify the critics who had charged the preliminary proclamation with an intent to incite insurrection, Lincoln omitted from the final text the phrase about doing no act to repress any effort by slaves to achieve freedom, and substituted: “And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, except in necessary self-defence.” The final version also described emancipation as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity”—which met criticism that the preliminary edict was informed by no convictions of justice.

These changes helped produce an outpouring of support abroad for the Northern cause that now embraced freedom as well as union. Henry Adams, secretary to his father, who was the American minister to the United Kingdom, reported that “the Emancipation Proclamation has done more for us here than all our former victories and all our diplomacy. It is creating an almost convulsive reaction in our favor all over this country.” Similar reports came from elsewhere abroad. The American minister to the Netherlands wrote that “the anti-slavery position of the government is at length giving us a substantial foothold in European circles…. Everyone can understand the significance of a war where emancipation is written on one banner and slavery on the other.”7

But what would happen after the war? The proclamation was a war measure that would cease to have any force in peacetime. What about the exempted areas? Even in the Confederacy, the proclamation might free many slaves but it did not abolish slavery as an institution. By 1864 Lincoln and his party had committed themselves to a constitutional amendment to end the institution of slavery everywhere in the United States. When Congress finally adopted the Thirteenth Amendment, holding that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist” within the US, and sent it to the states in 1865, Lincoln pronounced it “a King’s cure for all the evils. It winds the whole thing up.” It was the King’s cure he was never to see ratified.

Holzer and Masur would surely agree with David Von Drehle that 1862 was the year of Lincoln’s “rise to greatness,” a year that began with

the American experiment…on the brink of failure…. But when the first day of January came around again…[Lincoln] had steered himself and the nation from its darkest New Year’s Day to its proudest, and in the process Lincoln had become the towering leader who forever looms over the rebirth of the American experiment.

In occasionally breathless prose, Von Drehle recounts the dramatic military and political events of that year, interspersing them with human-interest stories of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary times.

The organizational structure Von Drehle has chosen to narrate these events is strictly chronological, with each chapter devoted to a single month. In less skillful hands such a structure might produce a dull, mechanical recitation of facts parading stodgily across the pages. But Von Drehle makes these pages crackle with life and energy. The narrative for February swings from the lavish White House dinner for hundreds of guests on the 5th to the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson on the 6th and 16th, back to the despair of the Lincolns at the death of their eleven-year-old son Willie from typhoid fever on the 20th to the fiasco of General McClellan’s use of pontoon boats to bridge the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry. They proved too wide by inches to fit through the outlet lock from the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. “I am no engineer,” Lincoln told McClellan’s chief of staff on the 27th,

but it seems to me that if I wished to know whether a boat would go through a hole, or a lock, common sense would teach me to go and measure it. I am almost despairing. Everything seems to fail! The general impression is growing that the General [McClellan] does not intend to do anything. By a failure like this we lose all the prestige we gained by the capture of Fort Donelson.

Lincoln’s problems with McClellan form one of the main narrative strands of Von Drehle’s book, and nobody has woven that strand more clearly into the events of 1862 than Von Drehle. For his part, McClellan repeatedly blamed lack of support from the Lincoln administration for his military reverses. A Democrat, McClellan did not like the turn toward a “hard war” of subjugation, emancipation, and confiscation of Southern property that took place in 1862. The general even toyed with the idea of publicly opposing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Northern Democrats were already exploring with McClellan the prospect of his running for president in 1864. Some of them, plus an alarming number of officers in McClellan’s military entourage, were even urging him to “change front on Washington” and carry out a coup to place himself at the head of the government.

Von Drehle takes seriously this threat of a military dictatorship under McClellan, and Richard Slotkin takes it even more seriously in The Long Road to Antietam, in which he depicts the growing divergence between Lincoln and his principal army commander over war aims and strategy. McClellan wanted to restore the Union of 1860; Lincoln now prosecuted the war to destroy slavery and the social order it sustained, and to build a new order on the ruins of the old. “The idea of a military dictatorship was not an idle fancy,” Slotkin maintains. “The possibility of dictatorship would define the stakes in the personal and political conflict between President Lincoln and General McClellan.”

This may overstate the case. It is quite true that in letters to his wife and to political associates, McClellan referred to having received “letter after letter…conversation after conservation…alluding to the Presidency, Dictatorship etc.” After the failure of his Peninsula campaign in the summer of 1862, which he attributed to the Republican administration’s machinations to make sure that he did not succeed, McClellan told his wife that he had been gratified to receive “letters from the North urging me to march on Washington & assume the Govt!!” It is also true that Lincoln had to treat McClellan gingerly because of the general’s strong Democratic constituency in the North and his popularity in the army.

But when Lincoln finally removed McClellan from command in November 1862, “there was some grumbling in the ranks,” according to Von Drehle, “and some rifles flung to the ground in protest, but the long-feared military coup never materialized.” Nothing in McClellan’s tenure of command became him like his leaving of it. “Stand by General Burnside [his replacement] as you have stood by me,” he told soldiers who did not want to let him go, “and all will be well.”

McClellan rode off into the sunset, but returned two years later to run for president against Lincoln. He lost that battle too, prompting a Union naval officer to comment wryly that “McClellan meets with no better success as a politician than as a general.”8 Ironically, McClellan’s limited victory in the Battle of Antietam had given Lincoln the chance to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, the most powerful symbol of “the shift from a strategy of conciliation to a war of subjugation,” according to Slotkin, “a shift that required the permanent sidelining of General McClellan.” Only then could the war become not merely a struggle to preserve the nation launched in 1776, but one to give that nation “a new birth of freedom.”

This Issue

November 22, 2012

The Politics of Fear

The Winner: Dysfunction

Election by Connection

-

1

The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Ray P. Basler, 9 vols. (Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), Vol. 4, p. 532. ↩

-

2

The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 5, pp. 344–345, 346, 350. ↩

-

3

William Whiting, The War Powers of the President, and the Legislative Powers of Congress in Relation to Rebellion, Treason and Slavery, 7th ed. (John L. Shorey, 1863). ↩

-

4

Selected Essays by Gideon Welles; Civil War and Reconstruction, edited by Albert Mordell (Twayne, 1959), pp. 237–239. ↩

-

5

Diary of Gideon Welles, 3 vols. (Norton, 1960), edited by Howard K. Beale, Vol. 1, pp, 142–145; The Salmon P. Chase Papers, Vol. I: Journals, 1829–1872, edited by John Niven (Kent State University Press, 1993), pp. 393–395. ↩

-

6

Times, October 7, 1862. ↩

-

7

Henry Adams to Charles Francis Adams Jr., January 23, 1863, in The Letters of Henry Adams, Vol. I: 1858–1868, edited by J.C. Levenson et al. (Harvard University Press, 1982), p. 327; James Shepherd Pike to William H. Seward, December 31, 1862, quoted in Dean B. Mahin, One War at a Time: The International Dimensions of the American Civil War (Brassey’s, 1999), p. 139. ↩

-

8

Aboard the USS Florida, 1863–1865: The Letters of Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to His Wife, Anna, edited by Robert W. Daly (US Naval Institute Press, 1968), p. 200. ↩