Let us say that you are a Mexican reporter working for peanuts at a local television station somewhere in the provinces—the state of Durango, for example—and that one day you get a friendly invitation from a powerful drug-trafficking group. Imagine that it is the Zetas, and that thanks to their efforts in your city several dozen people have recently perished in various unspeakable ways, while justice turned a blind eye. Among the dead is one of your colleagues. Now consider the invitation, which is to a press conference to be held punctually on the following Friday, at a not particularly out of the way spot just outside of town. You were, perhaps, considering going instead to a movie? Keep in mind, the invitation notes, that attendance will be taken by the Zetas.

Imagine now that you arrive on the appointed day at the stated location, and that you are greeted by several expensively dressed, highly amiable men. Once the greetings are over, they have something to say, and the tone changes. We would like you, they say, to be considerate of us in your coverage. We have seen or heard certain articles or news reports that are unfair and, dare we say, displeasing to us. Displeasing. We have our eye on you. We would like you to consider the consequences of offending us further. We know you would not look forward to the result. We give warning, but we give no quarter. You are dismissed.

1.

I heard the story of one such press conference a couple of years ago, shortly after it took place, and had it confirmed recently by a supervisor of one of the reporters who was present. It gives some notion of the real difficulty of practicing journalism in provincial Mexico, where dozens of reporters have been killed since the start of the century, some after prolonged torture. Different totals are given for the number of victims.

For example, Article 19, the British organization to protect freedom of expression, gives a figure of seventy-two reporters and photographers killed in Mexico since the year 2000, and of these, forty-five killed since the start of the administritation of Felipe Calderón, in 2006. Other organizations give a total of more than eighty. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), among others, lists only twenty-seven killed since 1992. It does, however, keep a separate, open list of journalists’ deaths in which the motive for each assassination remains unexplained by authorities. When these two sets of victims are added up the total is sixty-five. “Mexico has the highest number of unconfirmed cases in the world…and the real reason so many cases we examine are unconfirmed is that there’s no real official investigation [of these crimes] at all,” the CPJ’s director, Joel Simon, told me. “So we don’t know why they were killed.”

Whichever way one counts the total, those responsible for only three crimes against journalists have been tried, convicted, and sentenced since 1997, and in two of those cases there is widespread doubt that the convicted men were the minds behind the crime, or even that they pulled the trigger.

In recent years, all the murders of journalists and all but a few of the threats against them, as well as disappearances and kidnappings, have taken place in the provinces. While covering the trial of Raúl Salinas de Gortari, older brother of disgraced former president Carlos Salinas, back in 1997, I learned that reporting for one of the hundreds of small media outlets that exist outside Mexico City is hard and often humiliating work. Raúl Salinas was a powerful and unpleasant character. He could and probably should have been tried for many things in connection with the hundred or so million dollars he had languishing in various Swiss bank accounts, but he ultimately served ten years’ hard time on a murder charge for which the evidence was laughable. (The alleged skeleton of one of Salinas’s supposed victims was unearthed on his property with the assistance of a self-described seer. Eventually it turned out that, at the request of the main prosecutor in the case, the skeleton had been planted by the seer’s ex-son-in-law, who in turn had dug up his long dead father for the purpose.)

Farce or not, the judging of a former president’s brother, in a country where the powerful enjoy almost total impunity, was unquestionably the trial of the century. Under Mexico’s legal system, there was no jury, and the trial took place within a high-security prison a couple of hours’ drive from Mexico City. I went out there every day for a week, to wait for hours at a time under a harsh sun for the one day when the authorities would, more or less arbitrarily, allow public access to the proceedings.

Advertisement

My colleagues from the country’s principal news media turned out to be local reporters from the nearby city of Toluca, most of them stringers. I soon found out that they took turns among themselves covering the trial (or rather, waiting outside the prison for the occasional opportunity to cover the trial) so that each might have time to pursue the outside activities that allowed them to patch together a living. The reporter for one of the two principal television stations sold real estate in the mornings; another worked afternoons as a radio announcer. All were expected to recruit advertisers. (If memory serves, a commission on these ads was part of their income.)

Some arrived at the prison by bus. Several did not own computers. One had to borrow a tape recorder. They were not idealistic, but the job was exciting. They had clawed their way up the Mexican class system to find a career, and they were proud of themselves. It wasn’t clear how many of them had graduated from journalism school or even college. For better or worse, many provincial reporters still have not. They worked fantastically hard, longed for career training and respect, and knew a great deal more than they published or broadcast.

Given the circumstances, it would hardly be surprising if local reporters like the ones I knew back then were to be grateful for the envelope proffered by a drug trafficker as a sweetener to a death threat. Bribes, known as chayotes, are a long-established supplement to the income of journalists in Mexico.1

Such payments were promoted and made primarily by the government itself since the early days of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), and offered with greater or lesser subtlety according to the rank of the person to be paid. An editor from the provinces told me that the practice was more common in Mexico City, but an editor in Mexico City said it was the other way around. “Remarkably, [the chayote] has been impermeable to all the winds of modernity,” said Luis Miguel González, the news editor of a business daily, El Economista, and a literate and dispassionate observer of the world he works in. “It’s hard for foreigners to understand the lightheartedness with which the practice of the chayote is viewed in the general media,” he went on. “Chayobribes, chayotours, chayomeals are all part of the joke.”

Sometimes money is given to a reporter, a publisher, or an editor, specifically for the purpose of slandering a political enemy. Sometimes it is given in thanks by the subject of a particularly favorable story. Mostly though, the money is handed out, like a regular salary, to beat reporters by their sources. In exchange, the writers are expected to publish government press releases as if they were news stories and to keep their own reporting within bounds delineated by the chayote giver. High-level reporters who pride themselves on their independence would be offended by such bribery. Instead, as González put it, they might be offered the chance to be lied to by a high-level government source.

It is hard to determine how immoral the chayote might seem to Mexican reporters, given that the practice was institutionalized by their own government. Not to accept a bribe or emolument from an official can be seen as a hostile act—a threat, almost. Few editors or publishers can be counted on to stand behind a reporter who refuses to play by the rules. Even fewer pay a living wage. (In the state of Tabasco, where the Zetas are powerful, the enterprising Salvadoran journalist Oscar Martínez found out that reporters are paid 60 pesos—about $5—per story.)

There has been a great burst of reformism and housecleaning in the Mexican media starting in the mid-1980s—there are now any number of superb, and fantastically brave, reporters who struggle to report and publish stories on all aspects of Mexico’s difficult situation2—but the practice of chayotearing beat reporters has gradually crept back to pre-reform levels. As a working editor, El Economista’s González has to deal with these issues in often painful ways. “They will offer a free official trip somewhere. Then they’ll tell you that on the trip there will be a good news story. Turn down the trip and you lose the story.” My own very general impression over the years has been that the great majority of Mexican beat reporters see themselves as seekers of the truth who operate within extremely narrow confines. Or as González sums up their view: “Accept the bribe but don’t get corrupted.”

Which is to say that Mexican beat reporters’ dealings with the menacing drug traffickers in their neighborhood are not so different from their historical relationship to government officials. The distinction between dead reporters suspected by international watchdog organizations of being on the take from the drug trade and dead reporters suspected by those in political power of not being on the take from anyone is perhaps less useful in this light.

Advertisement

Let us say that a Zeta press conference makes a deep impression on reporter A, particularly after reporter B is murdered for collaborating instead with the police. Reporter A decides to tailor her stories to what she imagines would be the liking of those who are watching her, and even accepts specific instructions, guidelines, and requests. Let us say that one day she is murdered by enemies of the Zetas, who have spotted her as an enemy collaborator. In the unlikely circumstance that an outside observer could actually learn why and how it was that reporter A died, the question would remain: Was she involved with the drug trade or a victim of deadly blackmail? In either case, the likelihood is that both reporters A and B were merely trying to stay alive.

2.

I went recently to the charming city of Xalapa, capital of the state of Veracruz, to talk with officials there about a recent wave of killings of journalists—eight dead in just two years, two of them dismembered, their heads left near the door of another newspaper. Xalapa has a lovely climate, an ambitious university, one of the best museums in the country, and, in the last two years, a raging war between powerful rival drug groups.

The state also has a notable spokesperson, Gina Domínguez, so famous that she was featured on the cover of a local society magazine that month. An enormous bouquet of roses decorates her spacious office. Her staff, friendly and highly qualified, speaks of her effusively. Thanks to a change in state law, she now oversees public relations for all branches of state government and not just for the governor. It is common to hear that she is the real power in Veracruz. More poisonous online rumors point to her tour of duty as press secretary to Mario Villanueva—former governor of the state of Quintana Roo, now extradited to the United States on federal drug charges—and accuse her of bribing the editors of local and even national newspapers.

On the day I arrived, all the Veracruz newspapers carried a front-page story—lifted more or less whole from the press release issued by Domínguez’s office—about the arrest of four men and one woman. The headlines announced that with these arrests (which actually took place a week before the press conference), the killing of four of the eight reporters murdered in Veracruz since 2011 had just been solved. The detainees had confessed, saying that they had acted as hit men for the Pacific Coast drug group Cartel del Milenio.

Further, the press release and the media stories said, the accused had identified the killer of a fifth journalist, who, they said, had worked for the enemy camp, the Zetas. The suspects said that they had also killed “some” other reporters, which in turn had, according to the communiqué, “caused the deaths of still other reporters assassinated…by the Zetas.” Better yet, the group of killers had freely confessed, or so it was said, to an additional thirty-one homicides. Thirty-six killings solved at a single blow!

In her office, Press Secretary Domínguez spoke in such perfectly even tones, with an expression so utterly unshifting, that I have no memory of her personality. She blinked once, and changed the subject, when I suggested that reporters used to the official bribe system were now being asked to choose between the frying pan and the fire, but otherwise she surfed smoothly over every question.

Could I interview the detainees? She listed the intricate legal impediments to that. Why was it that the wave of crimes against reporters had increased so sharply when the governor she now worked for was elected? In Veracruz, as in the rest of Mexico, she noted, drug group warfare was always shifting from state to state, and the murder of journalists was one of the accompanying phenomena. The government’s record of successful struggle against violent crime was outstanding, she said coolly, and it had gone further than that of any other state in promoting more professional journalism. Had she in fact worked for the disgraced former governor of Quintana Roo, Mario Villanueva? Indeed she had, she said, for two months, and she had left that state long before his arrest.

Throughout the interview—she gave generously of her time—she stayed on message. “We have always maintained that the murder of these journalists had nothing to do with freedom of expression.” The five detainees’ confessions, she insisted, made it clear that the murder victims were only partially employed as reporters, and that the actions of reporters on the police beat were furthering the interest of los grupos criminales. In every case but one, she stressed, all the victims were linked to the police beat.

The following day, both Article 19 and the Committee to Protect Journalists mentioned the dearth of evidence provided by the Veracruz state attorney general. A few days ago, when I asked Dario Ramírez, head of Article 19’s Mexico regional office, if he knew how the case against the suspects was moving along, he explained why he didn’t. The logic of the government officials, he said, “is to let the cases ‘cool,’ without producing an effective result. There is no access to the investigation, so we don’t know what stage it’s in.”

3.

On November 13, 2008, the reporter Armando Rodríguez, who worked for the Juárez newspaper El Diario, waited in his car with his oldest daughter, then eight years old, while his wife got the youngest ready for preschool. She heard shots, and for a moment thought that it was just part of the general Juárez soundtrack. When she looked out the window seconds later it was too late. Riddled with bullet wounds, Rodríguez was slumped over his daughter’s body, whom he died protecting.

Armando Rodríguez—known everywhere as El Choco (for “chocolate”) because of his skin color—started out in journalism as the cameraman for Blanca Martínez, who was then a TV reporter. They married, and while Blanca became the editor of the local Catholic church weekly, Rodríguez persuaded a Juárez newspaper to hire him, and he transferred to El Diario as a reporter.

He worked the police beat hard, particularly at the time of a series of unspeakable feminicidios, or serial killings, of young Juárez women, and then again when the wave of drug violence started in 2008. An elder statesman on the police beat, Choco was respected by his editors and by his colleagues for his aggressive reporting.

“They said he was temperamental,” his widow told me over the phone, “but it was just because he was so passionate about his work.” The first time he got death threats the paper persuaded him to take a break because he needed an operation. Many other threats followed. In the weeks leading up to his murder, Choco Rodríguez had published articles linking relatives of the Chihuahua state attorney general, Patricia González Rodríguez (no relation), to the dr ug trade. On November 12 he wrote a story about the gangland execution of two police officers who, according to Choco, worked directly for the attorney general, pointing implicitly to the possibility that the attorney general herself had connections to the drug trade. The story ran in the issue of November 13, which hit the street around 1:30 AM. A few hours later, Choco was dead.3

I asked Blanca Martínez how the investigation into her husband’s murder was going and her voice got small. “That December they came to question me,” she said. “I can’t remember if they were federal or state police. They asked me about his work, they asked me if he carried a weapon. [He didn’t.] One of them told me that they had precise instructions [from the federal government] to investigate the case. That was the first and only time the government ever sought me out.” There were no arrests, she said. There were no new leads. The investigation was inactive. Years had passed before she was allowed to see the court files on her husband’s murder, and then only briefly. There was, additionally, the fact that the main federal investigator had been gunned down a year after the murder. His replacement was killed shortly afterward.

Few murders in Mexico have been the focus of as much media indignation or pressure as Choco’s. It has become a cause for Juárez reporters and editors and several media associations in Mexico City. The crime has also become a flagship case of sorts for the Committee to Protect Journalists, which is based in New York and is the most influential organization of its kind. In the fall of 2010, after many requests, the CPJ was able to meet with President Felipe Calderón, whose term in office is likely to be associated forever with the ill-fated decision to declare a military war on drugs, and with the atrocious violence that ensued.

During his conversation with the CPJ delegation, the president emphasized that he was just as concerned with the fate of journalists in Mexico as his visitors, and as determined to see justice done in the case of every crime against them. In fact, he said, the murder of Choco Rodríguez had just been solved; the culprit was a confessed hit man who had been under arrest for several months and had not previously mentioned murdering Rodríguez, but who had recovered his memory of this crime.

Weeks before the CPJ meeting with Calderón, a reporter at El Diario was contacted by someone who claimed to have a brother, a convicted murderer, doing time in the Juárez penitentiary. This brother was the leader of a gang of killers, and had confessed to several murders. But the source was concerned because the convict was being removed from prison every weekend and taken to a military base. There, he was being tortured mercilessly, and told to confess to the murder of Choco Rodríguez. But he continued to insist that he had not committed that murder.

The day after the CPJ delegation’s meeting with Calderón, the editors and reporters at El Diario were able to put the pieces of the puzzle together: the tortured hit man was called Juan Soto Arias, and it was he who had been identified by President Calderón as the confessed killer of Rodríguez. “Whatever limited confidence we had in the investigation disintegrated at that point,” Joel Simon told me. “Someone was acting in an incredibly cynical manner. We don’t know how high up that went. Regardless, the president told us information that was incorrect and easily confirmable as incorrect.” The investigation has been dead since that incident, “like all investigations into the killing of journalists,” as Simon pointed out. (Soto Arias reportedly remains in prison, serving a 240-year sentence for the murders he initially confessed to. He was never charged with the killing of Armando Rodríguez.)

One day recently I had a long phone conversation with Rocío Gallegos, who was Choco Rodríguez’s editor at the time of his death. Since that first murder, reporters have received many threats, and a young intern was assassinated.

El Diario is unusual in that it is relatively prosperous and concerned for the welfare of its news staff, Gallegos said. Staff reporters are given fellowships to attend journalism school and seminars. They have health and life insurance, and most are on a salary. While journalism in Tamaulipas, homeland of the Zetas, has all but vanished, news continued to flow out of Juárez, and El Diario, even when it became the most violent city in the world. (Thanks largely to a deal that appears to have been struck between the Pacific Coast drug mafias and the local drug runners, similar to a reported deal in Tijuana, violence in Juárez has greatly diminished in the last year or so.) Even before Choco’s death, the traffickers’ hostility to the media was made clear: a week before that murder, Gallegos recalled, someone placed a man’s severed head at the foot of a public statue honoring the city’s paper delivery boys.

I asked Gallegos, who is currently the news editor at El Diario, how life had changed at the paper in the long years of bloodshed. “We understood that we had to give up on exclusives,” she said. “Whether we got a scoop or not became irrelevant. [There were places] where you simply couldn’t send a reporter out alone.

“We were so unprepared for this situation!” she said.

It overwhelmed us. We’d come in from a scene where the victims’ mothers were crying, the families were crying, and then we had to sit down and write. Or it would be three in the morning and I’d find myself comforting a reporter who was weeping because she’d just received a death threat on her cell phone. You have to think: how have we been affected by all this? I think a great deal about those colleagues who have had to go out and photograph twenty corpses. How have they been affected?

I asked her what she would have wanted to see in these years of terror. “Justice,” she replied. “Less aggression. Greater safety. But above all, I would have wanted justice, because the murder of our colleagues has received no justice. I would like to know who killed them and why.”

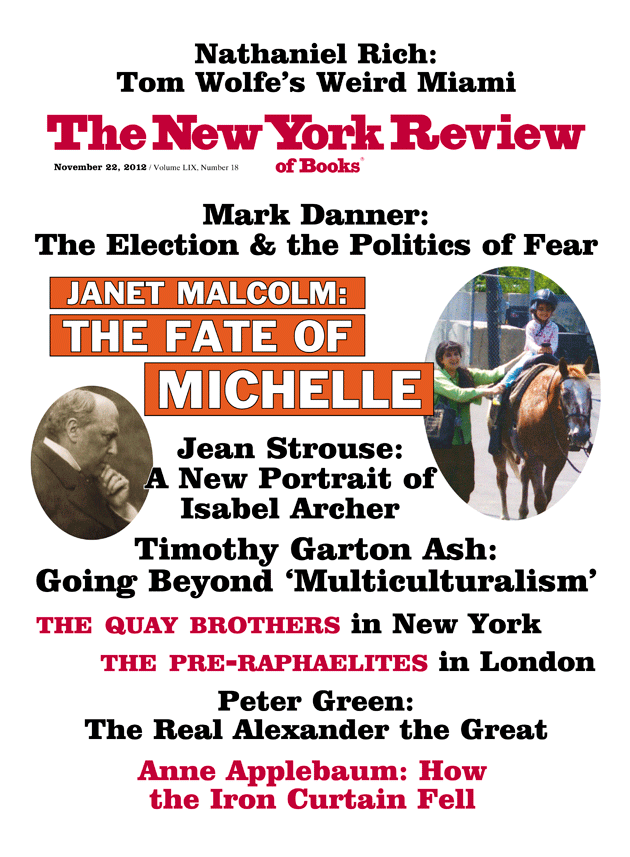

This Issue

November 22, 2012

The Politics of Fear

The Winner: Dysfunction

Election by Connection

-

1

Why the chayote, a prickly vegetable known as mirliton in New Orleans, should signify illegitimate money willingly taken is a mystery, but it is a word known by Mexicans in all walks of life, and a principal reason why the media are so little respected. Another common term for press bribes is embute, or “stuffing.” ↩

-

2

Interviews with a small sampling of these colleagues can be seen online (with English subtitles) in a half-hour documentary produced by Article 19, at vimeo.com/38841450. ↩

-

3

In 2010, in one of the drug war’s more grotesque episodes, the Zetas distributed a video recording of the torture of the state attorney general’s brother. Before they killed him, the brother stated on camera that he and his sister had both worked for a rival drug group, and that she had ordered the murder of Armando Rodríguez. The reliability of statements made under such conditions is, of course, nil. ↩