The title of Dave Eggers’s memoir, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000), brings two assumptions into sharp relation: that we want to read about suffering and that writerly genius manifests itself in the evocation of suffering. With comic hyperbole, the reader is promised someone to sympathize with and someone to admire; in this case, the same person. Meantime, the blurbish ring to the words reminds us that the book is born into a world of hackneyed hype and anxiously constructed celebrity. If our genius chose this puff for a title can his motives be pure, is his ego under control? Eggers is letting us know he wants to have some fun with this.

There are four hundred very full pages but the outline is quickly sketched. Aged twenty-one, Dave loses both parents to cancer. The family wrecked, he takes over the parenting of his eight-year-old brother Christopher, or Toph, and moves from Illinois to California to be near his elder sister Beth and brother Bill. No longer under stern parental control, Dave, excited, liberated, quickly understands that society feels somehow guilty in regard to orphans like themselves, offering generous subsidies and recognizing their victim status as a form of celebrity. The more society expresses this guilt, the more self-righteous Dave feels in his efforts to be an ideal guardian for Toph. Drawn toward journalism, blessed or cursed with a manic energy, sometimes constructive, sometimes destructive, frequently both, Dave hungers for visibility. He starts up a satirical magazine, Might, on the side of youth and liberal rectitude, and considers turning his parents’ sickness and death into a blockbuster memoir.

Dave is given to wild exaggeration. He loves to tell tales, forgivable because hilarious, endearing because so obviously the product of a youthful desperation to achieve. The exaggeration seeps into the memoir itself; an interview where Dave explains to a TV producer why he should be on a reality show becomes a fifty-page tour-de-force. Much of what he tells the producer beggars belief, while the length and elaborate nature of the interview suggest that Eggers is exaggerating for us what exaggeration there may have been at this encounter, assuming it took place.

Despite our amused skepticism, the technique works as memoir; this is the kind of person Dave is. We have not so much his life as his constant retelling of it. All is performance and persuasion with the present state of Dave’s mind the only topic on offer. Long conversations with Toph, for example, allow the younger boy to deconstruct, with sophistication beyond his years, the self-serving, pseudoethical positions Dave takes in his magazine. Rather than giving an accurate picture of Toph, it seems Dave is aware of his brother mostly insofar as he offers a foil to explore his own misgivings. After Toph lands one particularly eloquent blow, Dave protests: “You’re breaking out of character again.”

Is Eggers’s memoir actually about celebrity, or is it that a thirst for celebrity is the form that a certain kind of youthful vitality inevitably takes in the US? “You feel, deep down,” Toph says, “that because there is no life before or after this, that fame is, essentially, God.” Fame, as it were, puts order into chaos; life doesn’t make sense without it. “These are people,” says Dave of applicants to a reality show, “for whom the idea of anonymity is existentially irrational, indefensible.” But of Adam Rich, who in an attempt to ridicule the public obsession with celebrity had agreed to be described by Might as murdered, Dave wonders:

Could he really be doing all this for attention? Could he really be milking his own past to solicit sympathy from a too-long indifferent public?

No, no. He is not calculating enough, cynical enough. It would take some kind of monster, malformed and needy. Really, what sort of person would do that kind of thing?

Indeed. The cleverness of the memoir is to make Dave’s agonized concern about his possibly dishonorable motives for seeking celebrity another form of suffering with which to sympathize, and another performance to admire. The puzzle for the reader is that what we most like about Dave is precisely this lively, supremely slippery self-regard.

Two years later, in his first novel, You Shall Know Our Velocity! (2002), Eggers invents a charmingly schematic collision between monomania and altruism: two young Americans try to get around the world in a week giving away $32,000 in cash to anyone whose poverty might make them a worthy recipient. The difference in tone between fiction and memoir is not as great as you might suppose; we have a first-person narrator, Will, who is the only real character and consciousness for most of the novel, his close friend Hand being essentially a sidekick whose recklessly confrontational style is bound to make things happen around Will. It is thanks to Hand’s provocation of a group of louts that Will has had his face so seriously smashed that he is embarrassed to appear in public; he will not be seeking the limelight.

Advertisement

Yet Will has already achieved celebrity of a kind. A photograph of him installing a lightbulb was picked up by an advertising agency, which paid $80,000 to use it in silhouette on lightbulb packaging. “I felt briefly, mistakenly, powerful,” remembers Will: “My outline burned into the minds of millions! But then came back down, crashing. It was an outline, it was reductive. It was nothing.” In A Heartbreaking Work, Dave had remarked that the stories you tell about yourself to gain attention are no more than “snake skins” that cease to be you as soon as they are shed. It’s exciting to be known to millions, but disappointing that what is known is not really you. Celebrity is not the way forward. Giving away money, Will hopes, may offer a more real relationship with the world.

What precipitates the decision to make the trip, however, is a death. This is a frequent motif in Eggers’s stories: someone dies, a family or community is shattered, and narrative kicks off from a sense of grief and scandal. The victim here is the twenty-six-year-old Jack, who together with Will and Hand made up a threesome of friends, each balancing the other: Jack “had calm where I had chaos and wisdom where Hand had just a huge gaping always-moving mouth.” With the group’s force for stability gone, Will sets out with Hand to combine a week’s exotic tourism with some impulsive and random charity.

There is a Dumb and Dumber hilarity to the opening pages of You Shall Know Our Velocity: the young men’s ignorance and presumption as they plan their flights; their indignation when some bizarre itinerary (Greenland–Rwanda) proves impossible; their embarrassment approaching people (in Senegal) to give away money; the disruptive consequences of their capricious gifts, some as careless as tossing banknotes out of a car window or taping them to animals:

We found a group of boys working in a field…. They were perfect. But I couldn’t get my nerve up….

“This is predatory,” I said.

“Yeah but it’s okay.”

“Let’s go. We’ll find someone better.”

We drove, though I wasn’t sure it would ever feel right. I would have given them $400, $500, but now we were gone. It was so wrong to stalk them, and even more wrong not to give them the money, a life-changing amount of money here, were the average yearly earnings were, we’d read, about $1,600. It was all so wrong and now we were a mile away and heading down the coast.

Finally, someone states the obvious:

—You do more harm than good by choosing recipients this way. It cannot be fair.

—How ever is it fair?

—You want the control money provides.

—We want the opposite. We are giving up our control.

—While giving it up you are exercising power…. You want its power.

In 2005, in collaboration with other writers, Eggers published two extended polemical essays: Teachers Have It Easy: The Big Sacrifices and Small Salaries of America’s Teachers and Surviving Justice: America’s Wrongfully Convicted and Exonerated. In his three following full-length works, What Is the What (2006), The Wild Things (2009), and Zeitoun (2009), he chose to tell borrowed stories rather than invent his own. All three have to do with the struggle between chaos and order. Expanding Maurice Sendak’s classic children’s story, The Wild Things gives us a Max who seems very much a younger version of Dave in Eggers’s memoir, a boy who would like to be good but whose childish energy leads him to wild misbehavior. Sendak’s vision closely matches Eggers’s and developing it into a full-length novel Eggers has the advantage that he cannot be accused of promoting himself: there are, as Max likes to observe, “other people to blame.”

The other two books are more radical departures. What Is the What gives the true, though novelized, story of a Sudanese refugee who escapes genocide to emigrate to the United States, while Zeitoun, labeled nonfiction, tells of a house painter of Syrian origin, Abdulrahman Zeitoun, who remained in New Orleans to help during the flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina only to find himself arrested on terrorism charges, brutally mistreated, and imprisoned for almost a month. They are tales of heartbreaking suffering, but with the staggering genius of the author now free from suspicion of “milking his past” to achieve celebrity. It is as if, in penitential response to the fertile tension between renunciation and self-indulgence that energized the earlier books, Eggers were trying to eliminate anything self-regarding in the act of writing, imposing an indisputably constructive content and purposefulness.

Advertisement

The premise behind this exercise is that a writer’s talent can simply be switched away from his own concerns to write up, after long interviews and much research, the instructive experiences of others. The books do not bear this out. What Is the What opens with its hero Valentino Achak Deng being mugged and held hostage in his apartment in Atlanta. Bound and gagged, Valentino recounts in extended flashback the story of his infancy in Sudan, the destruction of his happy family in civil strife, and the terrifying vicissitudes of his escape. Doing so, he imagines addressing his words to his assailants, first a black man and woman, then their young son who watches TV while Valentino is bound on the floor:

TV Boy, you are no doubt thinking that we’re absurdly primitive people, that a village that doesn’t know whether or not to remove the plastic from a bicycle—that such a place would of course be vulnerable to attack, to famine and any other calamity. And there is some truth to this. In some cases we have been slow to adapt. And yes, the world we lived in was an isolated one. There were no TVs there, I should say to you, and I imagine it would not be difficult for you to imagine what this would do to your own brain, needing as it does steady stimulation.

This device, of flashback and indignant address, is tediously labored over many pages; suddenly Eggers seems a much less talented writer.

The situation improves in Zeitoun, where Eggers uses a third-person narrator and keeps the chronology fairly straight, bar long flashbacks that paint an idealizing picture of Zeitoun’s Syrian childhood and of the family he has formed with his American but Muslim wife, Kathy. The description of Katrina, the ensuing flood, Zeitoun’s attempts to help those stranded, his arrest and mistreatment, all make fascinating reading, but again Eggers undoes much that is good with labored dramatic filler: “it was growing ever more apocalyptic and surreal,” he tells us at once point. Some days after the flood begins, Zeitoun, in his canoe with a friend, sees a corpse.

Zeitoun had never imagined that the day would come that he might see such a thing, a body floating in filthy water, less than a mile from his home. He could not find a place for the sight in the categories of his mind. The image was from another time, a radically different world. It brought to mind photographs of war, bodies decaying on forgotten battlefields. Who was that man? Zeitoun thought. Could we have saved him? Zeitoun could only think that perhaps the body had traveled far, that the man had been swept from closer to the lake all the way to Uptown. Nothing else seemed to make sense. He did not want to contemplate the possibility that the man had needed help and had not gotten it.

It is hard to believe this rhetoric. Zeitoun is caught up in a devastating flood that he knows has caused deaths; he knows that for days the TV has been speaking of lootings and shootings. Disturbing as it is, a corpse would be far from unexpected or hard to categorize. But Eggers is determined to present Zeitoun as a paragon of decency, stability, and generosity—“Could we have saved him?” he wonders—this presumably in order to increase the sense of grievance when he is arrested; but the scandal of arbitrary arrest would be the same however pleasant or unpleasant the arrested man.

Later, when Zeitoun and his friends are questioned and then imprisoned in a large outdoor cage, we hear that the situation “surpassed the most surreal accounts he’d heard of third-world law enforcement.” Clearly Zeitoun had not read What Is the What. Cruel, stupid, unnecessary, and illegal his arrest certainly is, but Zeitoun does come out of jail in less than a month. All charges against him were dropped.

One aspect of the story seems to interest Eggers more than others. Imprisoned, Zeitoun wonders if he isn’t being punished for having believed himself chosen by God to save people from the flood. Again constructive actions are suspected of containing a germ of destructive self-regard. Perhaps there is simply no way of avoiding this ambiguity when acts of goodness draw attention to those who perform them. Eggers himself, for example, could be accused of gaining in public recognition from the charitable gesture of telling the stories of Zeitoun and Achak Deng. Clearly we are far away here from Will and Hand’s random charity in You Shall Know Our Velocity! yet once again we realize how hard it is to perform an act of public charity without equivocation.

If you seek to encourage a liberal attitude by offering an idealized view of an ongoing real-life narrative, you risk the eventuality that a new twist in that story, after your book is finished, could undermine the account you’ve given. Rereading now the happy picture of Syria painted in Zeitoun, it is hard not to think of events there today; hearing the recent news that Zeitoun, after castigating his daughters for their non-Islamic dress habits, today stands charged with hiring a killer to murder his now-ex-wife, some hard hearts will not only feel confirmed in their prejudices but may wonder if Eggers didn’t miss something about the man. These are not the kind of considerations that would normally fall within a reviewer’s brief, but the radical form of writing Eggers has chosen here makes them inevitable.

It is with some relief, then, that one opens A Hologram for the King to find that it is an absolutely ordinary novel. Alan Clay (as in “feet of”), fifty-four, failing in every department—work, home, health, romance—arrives in Saudi Arabia with a last chance to turn his life around: a usually idle private consultant, he is fronting a small team from the giant IT company, Reliant, which is bidding to be a major supplier for King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC), a vast development on the coast of Saudi Arabia. If Reliant gets the deal, Alan will be solvent again.

Eggers gets the ball rolling with great confidence and dispatch. On the trip over Alan met a woman he would have liked to know better, but failed to get her contact details; our subject is inadequacy, missed opportunity. On his first night in Riyadh he oversleeps, misses his transport out to KAEC, and finds on late arrival that the city so far comprises just three buildings in a desert and that the king, who is to assess their presentation, is not scheduled to put in an appearance anytime soon. To make matters worse, his team of two young technicians and a marketing director, Cayley, Brad, and Rachel, has been relegated to a large tent without adequate air-conditioning or Wi-Fi, the latter being essential for their plan to impress King Abdullah by projecting a hologram of a Reliant executive in London who will explain the details of the company’s bid. Every attempt by Alan to get information about the king’s movements and improve conditions in the tent is fobbed off. This situation remains static for several days.

Like previous Eggers heroes Alan swings between defeatism and wild optimism. One moment he thinks of running away from his American life and reneging on the debts that shamefully prevent him from paying his daughter’s college tuition; at others he feels he could “stride the world, a colossus, enough money to say fuck you, and you, and you.” But where Dave and Will in earlier books were on the excited brink of adulthood and full of energy, Alan is fading fast. He built a career selling Schwinn bicycles, manufactured in Chicago, but lost his job when production was moved to Asia.

His consequent decline is made emblematic of the decline of American manufacturing, American power, American confidence in the world. Alan had drawn a lot of his energy from his conflicted relationship with his ex-wife Ruby, but eventually they fell apart; similarly, tensions in the once fertile relationship between unions and management destroyed American enterprise. These are the two broken families behind our narrative. Meanwhile Alan has a growth on the back of his neck which he fears is cancerous; he hasn’t had sex for years.

Eggers stays remorselessly on theme. Conversation after conversation, flashback after flashback fills in the steps that brought Alan’s life and America to this. He phones his father, an erstwhile union leader in shoe manufacturing, and is mocked for his naiveté when, to save Schwinn, he betrayed their traditional workers and helped relocate production. An acquaintance tells of losing a contract to provide quality glass for the Ground Zero development to a Chinese manufacturer. A close friend of Alan’s who has sought to free himself from materialism through Emersonian transcendentalism has killed himself by walking into a Massachusetts pond. Rachel, Cayley, and Brad, Reliant’s team, are youngsters who have no knowledge of manufacturing and do nothing but stare at their computers; they seek no relationship with Alan, or he with them; rather, he is afraid that they will see him, rightly, as utterly impotent.

Here is a problem for the novel. We never believe that a man like Alan would be fronting a crucial bid by a major IT company. He knows nothing of IT, nor gives any indication of having done much homework. He was chosen because he once had a brief acquaintance with a nephew of the king; Arab royalty, however, is famous for its multitudinous families and this particular nephew is known to be a loser. Could Reliant be so inept? Out at KAEC Alan mooches about the site musing over his stalled life, frequently stumbling and hurting himself. Back at the hotel he gets drunk on the ferocious liquor provided for him by a bored Danish ex-pat eager for sexual pleasure Alan can’t offer; drinking, he writes letters to his daughter Kit in which he seeks and fails to offer her useful wisdom. Eventually he takes a serrated knife to the growth on his neck in a gesture of self-harm that always seems to lie just below the surface of those characters closest to Eggers, men frustrated by the impossibility of turning their natural energy to good use. The problem with America’s decline, for Alan, is that it has left him without a harness to work in, taken away any reason for not drinking himself sick; only drunkenness gives him an illusion of vitality and purpose.

Mightn’t KAEC itself provide such a reason? Eggers’s characters like to form purposeful groups who build things together. In the memoir Dave has his magazine. Zeitoun looks forward to rebuilding New Orleans. Eggers himself has his publishing house, McSweeney’s. As his bibliography suggests, he likes collaborations, individual energy subsumed in the communal will. His books carry long lists of acknowledgments, as if he were eager to convince us that he is not the only person responsible for what we are reading. So in A Hologram Alan is intensely drawn to the vision of the future KAEC. “He wanted to believe that this kind of thing, a city rising from dust, could happen.” He imagines staying in the city and becoming part of the project. Alas, as its name suggests, the development of King Abdullah Economic City depends entirely on the caprice of an absent king.

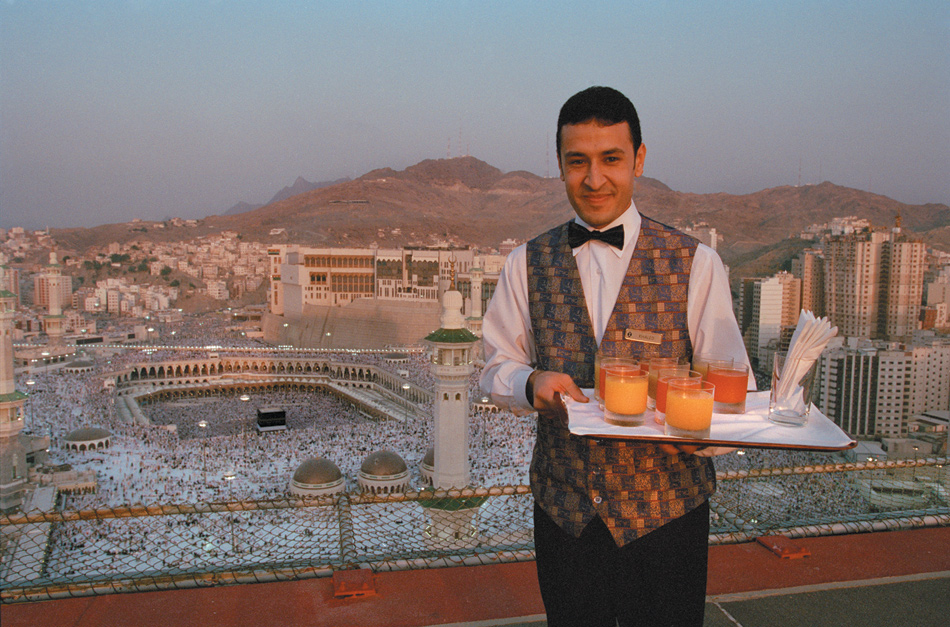

Alan’s one meaningful contact with Saudi Arabia is his driver, Yousef, whom he immediately imagines might be his son, someone he can help. A source of comedy, the savvy young Yousef is concerned he might be murdered by the man who married the girl Yousef himself was in love with and who now continues to send him erotic text messages at great risk to both their lives, given Saudi laws on adultery. In keeping with Eggers’s focus on the tension between constructive and destructive energies, what fascinates Alan in Saudi Arabia is the gap, everywhere evident, between a rigidly ethical Islamic façade and people who seem to be doing whatever the hell they want. But this world is too puzzling and alien for Alan to have any useful part in it. In the end he is happiest when, in the country with Yousef, he sees some men building a wall and, to the bewilderment of his driver, persuades them to let him help.

Cleverly set up, the novel falters. The references to American decline and Saudi duplicity begin to weary. Everything is a little too schematic, symbolic, and significant. Alan has what proves to be a lipoma removed by a Saudi Arabian woman surgeon aided by a Chinese, a German, an Italian, and a Russian, with an Englishman “observing.” Afterward he manages to start a romance with this surgeon who invites him to her home by the sea, where they swim together, she, in her late fifties, wearing only her bikini bottoms to appear, to any distant snooper, as another man. Such scenes are not easy to get right:

He had never seen anything more beautiful than her hips rising and falling, her legs kicking, her naked torso undulating. She swam out farther and paused where the floor dropped precipitously into deepest blue.

Finally Alan has found someone he can connect with. However, as the couple are about to make love, he is blocked by memories of his wife, thoughts of the mess his life has become. If Eggers’s earlier books are fired with the tension between selfish energy and constructive goodness, chaos and order, Alan has neither the energy that would generate chaos, nor a setting—family, business, nation—in which to construct. This is a melancholy performance, but so much more alive than the “true stories” that preceded it.