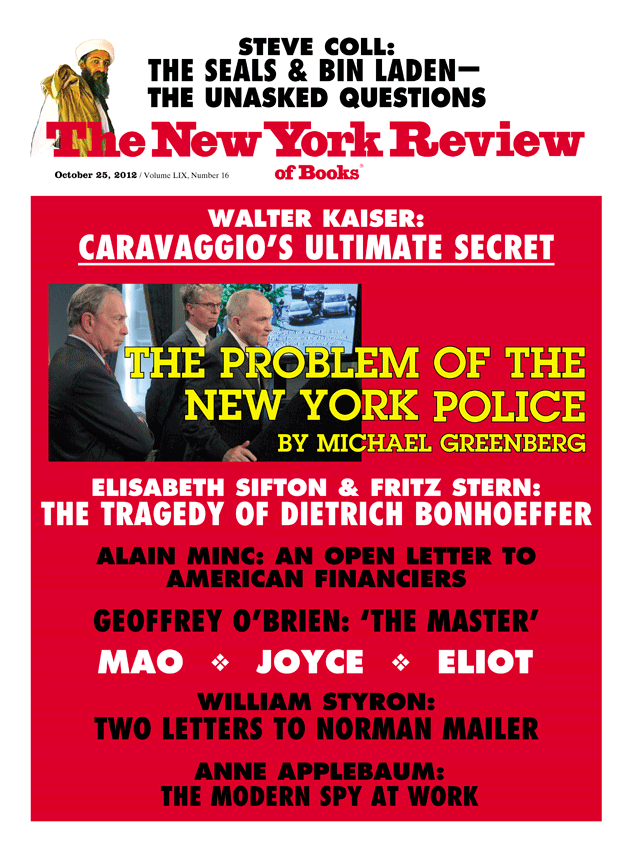

Shortly after noon on May 29, 2002, the Irish government jet touched down at Dublin airport. As the prime minister and a large media contingent waited by the runway, the minister for culture, Síle de Valera, descended the steps, holding in front of her a case—or should one say a reliquary?—containing five-hundred-odd sheets of paper. Journalists were given a brief glimpse of the precious cargo: early drafts of eight episodes of James Joyce’s Ulysses and amended proofs of Finnegans Wake, purchased for €12.6 million (about $15.5 million). De Valera, whose grandfather Éamon dominated Irish politics between the 1930s and the 1960s, when the work of most serious Irish novelists was banned, declared the arrival in Dublin of these sacred relics a “monumental event in Ireland’s literary and cultural history.”

For those of us who had known the thrill of reading Joyce when he was still the scandalous author of dirty books, this was a bittersweet moment. It was good, of course, that one of the greatest of Irishmen was at last being honored in his own country, and especially in the city that was, even after he left it for the last time in 1912, his imaginative universe. But Joyce really is dirty and scandalous. Those precious pages, for each of which the Irish government paid around $30,000, stink of flesh, ordure, and bodily fluids. They are steeped in forbidden thoughts and dishonorable desires, in secrets, blasphemy, and sex. They were not made to become holy relics. Censorship and opprobrium may have been a cruel fate for the living Joyce, but elevation to sainthood after his death is not necessarily a better one.

Yet the great sinner, once a literary Bolshevik (Shane Leslie) whose “illiterate, underbred” Ulysses was the “nauseating” effluent of a “self taught working man” (Virginia Woolf), seems doomed to sanctity. He is now not merely a great official Irishman but a great official European: in 2009, the president of the European Central Bank, Jean-Claude Trichet, placed him in a new Holy Trinity that defines Europeanness, a term that means, he said, “that I live in a modern literary atmosphere that is influenced directly and indirectly by the Czech Kafka, the Irishman Joyce and the Frenchman Proust.” When the young Joyce was bored out of his mind, working in Rome as a correspondence clerk for the Nast-Kolb & Schumacher Bank, it might have been of some comfort to know that he would one day be providing the cultural underpinning for the euro.

This veneration might not be so bad if it were based on his work rather than his life, but it is hard not to suspect that Joyce is now more revered than read. The dirty, slippery, uproarious, demented, and hysterically funny Joyce of the books is one thing. The artistic martyr of the life, the hero who gives up everything for art, is quite another. Joyce the writer spent his life subverting inherited narratives of every sort. Joyce the man, on the other hand, fits perfectly into a preexisting narrative, contained within a few words of Isaiah 53:3: “He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.” Those lines, of course, were taken in retrospect to apply to Jesus. In our secular age, they may be read as foreshadowing the apotheosis of Joyce, who was crucified by the philistines before ascending into the heaven of eternal worship.

Joyce himself helped to create this narrative. His great booster, Ezra Pound, called him “James Jayzuz,” and linked him with the dead Irish nationalists Patrick Pearse and Terence MacSwiney as having “the same mania for martyrdom”: “it is the Christian attitude; they want to drive an idea into people by getting crucified…. I think Joyce has got this quirk for being the noble victim.” Bernard Shaw sent Pound a postcard of José de Ribera’s painting The Dead Christ, asking, of Joyce: “Isn’t it like him?” Joyce referred to himself—mostly in jest—as “Melancholy Jesus” and “Crooked Jesus”—names his great supporters and publishers, Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, used in their private conversations about him. In Finnegans Wake, Joyce refers to a semiauthorized biography by Herbert Gorman, which Joyce himself did much to shape, as “the Martyrology of Gorman”—typically a pun: the same title also refers to a twelfth-century calendar of saints. Richard Ellmann, in his own monumental biography, notes that “without saying so to Gorman directly, [Joyce] made clear that he was to be treated as a saint with an unusually protracted martyrdom.”

If he was not being crucified, Joyce was being burned at the stake. Giordano Bruno of Nola, burned for heresy, was one of his touchstones. His very early essay “The Day of the Rabblement” begins with a reference to Bruno. Near the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Daedalus discusses him with one of his university teachers, Reverend Charles Ghezzi: “He said Bruno was a terrible heretic. I said he was terribly burned.” While Joyce did not actually meet the same fate, he liked to think that he shared it through the persecution of his books. In 1919, when copies of the Little Review containing an extract from Ulysses were seized and burned by the US Post Office, Joyce told his patron Harriet Weaver that “this is the second time that I have had the pleasure of being burned while on earth.”

Advertisement

What’s interesting is that the first time, in his mind, was when the proofs of his first prose book, Dubliners, were burned by the publisher, George Roberts, who lost his nerve over fears of libel. In fact, this burning was part of Joyce’s self-made myth of martyrdom. As Gordon Bowker astutely notes in his new biography, “the book was not burnt but guillotined and the sheets used for packing; however, for Joyce, a burning was far more dramatic.”

Such moments of skepticism about the narrative of martyrdom do not, however, prevent Bowker from framing Joyce as an essentially religious figure. He begins by telling us that “Joyce’s religious dedication to authorship also picks him out as a writer in the romantic tradition of total commitment, suffering near poverty and financial dependency for much of his life in his determination simply to write.” Later, he talks of Joyce’s willingness to endure hunger as a poor student in Paris as evidence of “the depth of his commitment to his new religion of art.” The evidence of his own book suggests that this kind of piety about Joyce is utterly misplaced, but the myth of the martyr is simply too potent to be dispensed with. The lives of the saints set down a pattern—early spiritual enlightenment, estrangement from family, exile, suffering, scorn, ascension into heaven, and perpetual adoration—that fits Joyce all too snugly.

Much of it, however, is nonsense. Joyce had his share of human suffering—the physical pain of his malfunctioning eyes and the emotional pain of watching his beloved daughter Lucia descend into mental disturbance. But this is the kind of suffering that is inflicted by life, not by art. Had Joyce stayed in that bank in Rome, glaucoma and cataracts would not have spared him the agony and semiblindness that made his later decades so difficult. And however nicely it serves as a moral tale of the curse of great creativity, there is no evidence that Lucia’s illness was related to her father’s obsessive dedication to his writing. The children of farmers and dentists can suffer from schizophrenia too. The attempt to make these vicissitudes into a price that Joyce paid for his art, like Prometheus tormented for stealing the fire, is often irresistible but nonetheless deplorable.

As for hunger, Joyce was hardly the first student to have to miss a few meals in Paris (where he briefly studied medicine when he was twenty-one). Bowker reports his reduction to such basic fare as “hard-boiled eggs, cold ham, bread and butter, macaroni, figs and cocoa”—not exactly starvation rations. Thereafter, there is precious little evidence that Joyce ever had a sustained period when he could not afford to eat or did not have a roof over his head. He had to work at some boring jobs before he became famous—the bank in Rome, teaching English in Trieste—but neither is likely to have been more dispiriting than, say, Leopold Bloom’s attempts, in Ulysses, to sell advertising for newspapers.

Far from being doomed to poverty by his art, Joyce was extraordinarily blessed with patronage. The idea of him “suffering…financial dependency for much of his life” is very funny. Which of us would not embrace such suffering? Bowker, following Ellmann, records that by 1923 alone, Harriet Weaver had given Joyce, out of pure admiration for his talent, £21,000—the equivalent of not far off a million dollars in today’s money. Economically, if not spiritually, Joyce was a minor member of the imperial rentier class, living off Weaver’s family investments in the Pacific, Canada, and Johannesburg. He also got money from the British government, from Edith Rockefeller McCormick, and, of course, from friends and family, especially his unfortunate younger brother, Stanislaus, from whom he relentlessly leeched money during the Trieste years. He even earned significant royalties from Sylvia Beach’s famous edition of Ulysses, before the book was unbanned in the US and Britain: 120,000 francs, enough, in provident hands, to rent a good apartment in Paris for about six years. Yet “please wire 2,000 francs tomorrow without fail” is as characteristic an expression of Joyce the man as “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay” is of Joyce the artist.

Advertisement

Joyce’s bouts of poverty were the consequence not of artistic self-denial, but of flagrant improvidence—a trait he inherited, along with a fine singing voice, a fund of tall stories and lurid phrases, and a taste for drink—from his feckless father John. To the life of the poète maudit, he preferred the life of Reilly. In his later years, it is true, he spent a lot of his money on medical bills for himself and Lucia, but a lot more of it went on extravagant meals, good wines, flamboyant tips, taxis, grand hotels, Chanel dresses, and fur coats. His was a peculiarly luxurious form of poverty.

There is, perhaps, more to be said for the other side of the martyrdom narrative—persecution. Joyce did indeed suffer infamously from censorship, both formal and informal. Ulysses, published in 1922, was not lawfully available in the US until 1934 and in the United Kingdom until 1936. Both ignoramuses and people who should have known better (like Virginia Woolf and D.H. Lawrence) called him all sorts of names. But he did not suffer for very long the much more painful fate for writers—indifference. Even before he had written anything of note, he was being heralded in Ireland as the coming man. His twenties were a time of frustration and neglect, but from the time the first installment of A Portrait was published by Dora Marsden in The Egoist on his thirty-second birthday in 1914, until his death in 1941, Joyce was talked of, written about, argued over.

The intensity of the hatred he aroused was at least matched by the ardor and generosity of his admirers. He had great fighters in his corner, most of them women (many, indeed, lesbians): his lover and later wife, Nora Barnacle, Weaver, Beach, Jane Heap, and Margaret Anderson (who risked prison to serialize Ulysses in the Little Review), and Pound, the P.T. Barnum of Modernism, who adopted his cause with all the ferocious zeal at his command.

Again, though, the notion of persecution and isolation was important to Joyce’s own self-image, so much so that it is easy to forget that many of his self-declared enemies showed him extraordinary forbearance. It was crucial to the young Joyce, for example, that he distance himself from the most important literary movement of his time in Ireland, the Abbey Theatre group with W.B. Yeats, John Synge, and Augusta Gregory at its core. They were Protestant nationalists with a strong attachment to mystical notions of peasant authenticity. Joyce was Catholic, urban, and allergic to mysticism. Even though he in fact knew long passages of Yeats’s poetry by heart, he had to pretend otherwise.

He went out of his way to be rude, insulting, and insufferably arrogant toward the Abbey group. He attacked them in “The Day of the Rabblement.” When Yeats met him and asked him to read some of his poems to him, Joyce, then twenty, told him, “We have met too late. You are too old for me to have any effect on you.” According to Yeats, he also “began to explain all his objections to everything I had ever done.” He mocked Synge, Gregory, and Yeats in a nasty and sexist way in his poem “The Holy Office,” dismissing the Abbey as a “mumming company” and Yeats as “him who hies him to appease/His giddy dames’ frivolities/While they console him when he whinges/With gold-embroidered Celtic fringes.” He spread (false) rumors that Yeats and Gregory were lovers. And how did they repay him? With patience, kindness, and practical support. Yeats, in particular, did everything in his power to help Joyce in large and small ways, meeting him from the 6 AM train in London when he was on his first trip to Paris, introducing him to Pound, helping to secure him a grant from the Royal Literary Fund, and telling everyone who mattered that he was “a genius.”

If the martyrology is ditched, however, what remains? Is biography to be nothing more than an exercise in reverse alchemy, transmuting the gold of Joyce’s art back into the leaden materials of his mundane existence? A mere debunking would be just as much of a distortion as the myth of sanctity. Bowker struggles to find an overarching narrative that can accommodate both the right degree of skepticism and the epic scale of Joyce’s achievement. His book is a very useful and readable updating of Richard Ellmann’s classic life—a biography so magisterial that no one has really attempted to compete with it since its first edition in 1959.

Other biographers have instead concentrated on single episodes or peripheral characters: Peter Costello’s James Joyce: The Years of Growth, 1882–1915, John McCourt’s excellent The Years of Bloom: Joyce in Trieste, 1904–1920, and the biographies of Joyce’s father by Costello and John Wise Jackson, of Nora by Brenda Maddox, and of Lucia by Carol Loeb Shloss. Bowker weaves their findings into Ellmann’s and adds substantial new discussions of Joyce and Nora’s wedding in London in 1931, the composition of Finnegans Wake, and Lucia’s illness. All of this makes his biography the most comprehensive compendium of information on Joyce’s life yet written.

What it lacks, however, is a larger narrative frame. Unable to shake off the notion of Joyce as a secular saint, yet obviously aware that it makes little sense, Bowker struggles to plot a middle course between hagiography and disillusion. He opts for an insistent linking of life to art, of incidents in Joyce’s ordinary existence to those in his books. The hope, presumably, is that this will do justice both to the banality of day-to-day fact and to the transformative power of Joyce’s imagination.

This is, though, a highly questionable procedure. It is no secret that Joyce continually drew on real people, places, and incidents, or that he pestered Dublin acquaintances for precise details about streets, shops, and families. But how much all of this really tells us about him is open to question. Bowker might have taken some warning from Stephen’s insistence in A Portrait that “the personality of the artist…refines itself out of existence, impersonalises itself, so to speak” in the work of art:

The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible…paring his fingernails.

Stephen, a highly satiric and skeptical self-portrait, arguably refines his creator, Joyce, almost out of existence. The successive versions of himself in Stephen Hero (unpublished in Joyce’s lifetime), A Portrait, Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake are ever more abstract, ever more distant from raw experience.

In any event, the search for precise real-life origins can lead into blind alleys. To take the most obvious example, Bowker tells us that in 1904, the year in which Ulysses is set, Joyce got into a drunken fight with a soldier and was rescued by a man called Alfred Hunter (“reputedly a Jew and a cuckold”), who took him to the house where he lived with his wife, Marion: “The street, the wife and Hunter…supplied the germ of the idea which later evolved into Ulysses, with Hunter as the prototype of Leopold Bloom, and his wife lending her reputation and name at least to Molly Bloom, née Marion Tweedy.” Later, Bowker is even more emphatic, telling us that Joyce’s task in writing Ulysses was to “transform the story of his rescue by Alfred Hunter into a great Dublinesque satire.”

Where does this story come from? Bowker takes it from Ellmann’s second edition, whose source note reads: “W.P. D’Arcy, a friend of Joyce’s father, heard the story from John Joyce; letter to me from D’Arcy. Other confirmation is lacking.” That letter was written in March 1960. A thirdhand Dublin yarn recalled fifty-four years after the supposed event is rather boggy ground on which to build so large a claim, especially since Hunter was not in fact Jewish. It is possible that the Hunter story sparked the creation of Ulysses, but just as plausible that Ulysses gave rise to the Hunter story.*

There is another difficulty with the search for real events that explain the books: Joyce’s work is shaped as much by absences and nonevents as by those things that actually happened to him. It is, for example, of immense significance that Joyce’s exile did not take the obvious shape. Almost all of his important Irish predecessors and contemporaries lived in London and defined themselves in some way as opponents or subverters of English society. Joyce simply ignored London in the years when he was creating himself, evading entirely the dilemma of the Irish writer’s need simultaneously to play up to and prey upon the English. As he explained to Arthur Power, in London’s “atmosphere of power, politics and money, writing was not sufficiently important.” In Dublin, on the other hand, “there was the kind of desperate freedom which comes from a lack of responsibility, for the English were in governance then, so everyone said what he liked.”

Another great absence in Joyce results from his extraordinary ability to be unaffected by World War I. Apart from the inconvenience of having to move to Switzerland to escape it, Joyce had no use for the great cataclysm of contemporary Europe. So much else in Modernism—T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, for example, published in the same year as Ulysses—is obviously shaped by it. If we did not know that Joyce already had the radical form of Ulysses in his head, it would be easy to imagine that book’s assault on all official pieties as a response to the disaster. But neither in form nor in content is Joyce’s work seriously affected by the war.

It is telling that Bowker, absorbed as he is in Joyce’s world, refers to the failed 1916 uprising in Dublin as having “disturbed…the peace of the British Empire”—news, surely, to all the poor Tommies on the Western Front. Risible as the claim is, it is somehow in keeping with Joyce’s breathtaking lack of interest in the Great War. And this is part of what makes Joyce so difficult a biographical subject: often, the most momentous drama lies in what he is blithely choosing not to do.

Perhaps, then, if we dump the martyrology, all we are left with are holes and absences on the one hand and, on the other, a reductive search for the mundane reality behind Joyce’s great fictions. Or perhaps not, for there are surely two ways in which Joyce can be viewed, without piety or secular religiosity, as a heroic figure. There is, in the first place, a remarkable courage in his willingness to conduct an unparalleled neurolinguistic experiment within his own mind. In writing Finnegans Wake, he induced in himself a decades-long brainstorm, a state of associative mania in which practically every word that came into his head, in every language he knew, was pulverized, split, and recombined into as many possible meanings as it could be made to bear.

One has to be skeptical about psychoanalysis by proxy, but Carl Gustav Jung, who plowed humorlessly through Ulysses and who attempted to treat Lucia, surely put his finger on something when he wrote that Joyce’s “style is definitely schizophrenic, with the difference, however, that the ordinary patient cannot help himself talking and thinking in such a way, while Joyce willed it and moreover developed it by all his creative forces.” Joyce willed himself into the kind of linguistic derangement that would be, for others, a terrifying madness. In the process he created Finnegans Wake—a work unlike anything there had ever been before and perhaps ever will be again. If we must have a religious analogy, it is not that of the saint but of the shaman, who has the courage to inhabit the dark terrain beyond the rational world and to bring back the tales of what he has seen (or rather in Joyce’s case heard) there.

More simply, there is the heroism that is utterly lost in all the reverence and martyrology: the fearlessness of Joyce’s comedy. In 1900, the seventeen-year-old Joyce spoke to a university debating society on drama and life: “Life we must accept as we see it before our eyes, men and women as we meet them in the real world…. The great human comedy in which each has a share, gives limitless scope to the true artist….” But these two tasks—to accept men and women as they really are and yet to revel in the “great human comedy”—are not easy to combine. Utter realism generally defeats comedy. Joyce looked more unflinchingly at men and women than anyone had done before—at their follies, betrayals, cruelties, and delusions, their dirty little minds and their inglorious secret impulses. Astonishingly, he managed to find them even more comic—responding not with the cruel laughter of contempt or the bitter laughter of absurdity but with the forgiving laughter of an infinite tolerance.

Bowker’s biography is sturdy rather than beautiful, but it has one rather beautiful image. It is Nora’s complaint to a friend that she has difficulty sleeping. Asked why, she explains that “I go to bed and then that man sits in the next room and continues laughing about his own writing. And then I knock at the door, and I say, now Jim, stop writing or stop laughing.” Joyce’s glory was that he refused to do either.

-

*

As a further note of caution, it might be borne in mind that Dublin folklore contains “witness” accounts by those who claim to have known Leopold Bloom himself. ↩