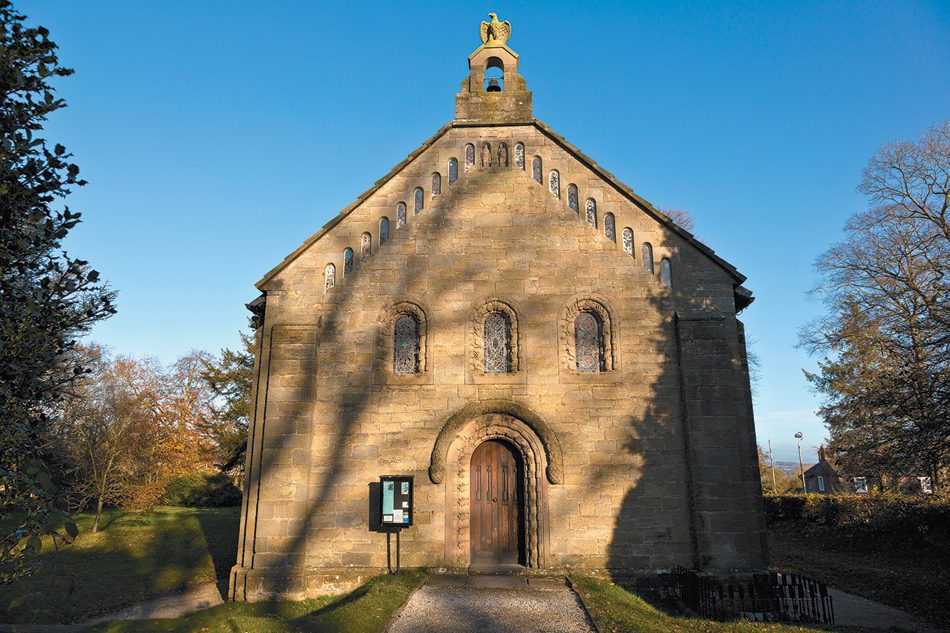

In the county of Cumbria far to the north of England, a land of ancient feudings alongside the Scottish border, stands a small stone village church built in 1842. So remarkable is this building that it stops in their tracks almost everyone who sees it. The Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti after visiting St. Mary’s church at Wreay in 1869 described it as a real work of genius, “a most beautiful thing.” A century on, the architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner judged it “a most impressive and in some ways amazingly forward-pointing building,” astonishing in its originality.

A contemporary British architectural authority, Sir Simon Jenkins, Chairman of the National Trust, includes St. Mary’s in his book England’s Thousand Best Churches, calling it “one of the most eccentric small churches in England,” a building which “but for the severity of its stone, might be on a hillside in northern Italy.” The chosen architectural style was Italian Romanesque with Lombardic rounded arches, surprising in an England in which Puginesque soaring spires were coming into fashion. The interior of the church was made rich and strange with carvings of flowers, butterflies, pomegranates, and the symbolic pinecones that give Jenny Uglow’s book its title. Even more unusual at a time when women were not trained in architecture is the fact that St. Mary’s was created from inception to completion by a local woman, Sarah Losh.

Losh came from a wealthy Cumbrian family of landowners and entrepreneurs. She was particularly fortunate in the Losh family’s local prestige and financial resources. St. Mary’s church might well have been less extravagantly original if Miss Losh had not been able to call the tune.

The expansive spirit of the time also had its impact on her ambitious, self-confident creativity. Sarah Losh was born in 1786. She grew up in a period of transition and excitement as the dawning of Romanticism coincided with the challenge of industrial expansion. Jenny Uglow’s great skill as a biographer is that of moving easily between the personal narrative and broader social background. She lucidly portrays the ever-widening horizons and the inherent conflicts of early-nineteenth-century England in her empathetic, scholarly, deeply absorbing book.

In explaining the genesis of St. Mary’s church we need to first see Losh in her local setting, growing up in the small village of Wreay, five miles south of what had originally been the ancient, remote walled city of Carlisle. The village community was a very small one, recorded in a 1794 History of Cumberland as containing “twenty-one families, sixty men and fifty-four women.” Sarah’s father, John Losh, was involved as his forebears had been in the day-to-day running of the village as head of the ruling body, the Twelve Men. Losh herself had a strong feeling for Wreay. Her designs for the new church and for other village buildings show her way of combining local responsibilities with highly Romantic aspirations.

She had a deep understanding of the dramatic landscape in which she had been reared. Westward from Wreay are the mountains of the Lake District with the rocky Pennines to the east. The sheer stoniness of the local terrain is reflected in her buildings, as are the sudden lovely visual surprises of that watery countryside of springs and becks and fells.

Sarah was a highly educated woman, a fine mathematician, a Greek and Latin scholar, and an intrepid reader whose appreciation of the landscape went far beyond the emotional and tactile. She joined in the enthusiasm for antiquarian studies that was sweeping across England in the first part of the nineteenth century. Losh developed an understanding of her country and its history that influenced profoundly her concept of a church. She understood the foursquare architecture of the defensive northern English towers and castles. She knew the great cathedrals of Carlisle and Durham and abbeys and smaller churches throughout Cumberland, stalwart solid buildings in the Saxon or round-arched Norman style.

Uglow shows Sarah Losh to be “a child of the Regency, when manners were broader, wit harder and when women, even among the gentry, were raised to know their own mind.” She points out how Losh in many ways anticipated women like George Eliot’s Dorothea in Middlemarch, a novel set in the 1830s. Dorothea, as Eliot’s readers will remember, has her own neighborhood building plans in mind.

Uglow, the biographer of both George Eliot and Elizabeth Gaskell, has an incisive understanding of female psychological and intellectual history and of how women, especially women in provincial England, were gaining confidence in thinking and acting independently as the nineteenth century progressed. As a young woman Sarah Losh was tall and handsome with light brown hair, reportedly a belle of the ballrooms in Carlisle. But she resisted marriage. She seems to have relished the opportunities then open to a woman of independent means. Her only living brother, Joseph, was ailing and mentally disabled, always needing to be cared for. Clearly he would never be able to inherit the family estate. In a sense Sarah replaced him, filling his role eagerly as the child of promise, the serious and highly focused “scholar son.”

Advertisement

Like the young men of the period she became an avid European traveler. She made her own Grand Tour, with her sister as companion. Since the death of their mother when Sarah was in her early teens, she and her younger sister Katharine, an easier, more lively, and less driven personality, had been inseparable. In 1816, when the continent had just been opened up to travelers after the Napoleonic wars, Sarah and Katharine set off through France to Switzerland, crossing the Alps and proceeding on through to Italy. This was the famous summer when Byron, Claire Clairmont, and the Shelleys were staying on the shores of Lake Geneva and Mary Shelley had embarked on Frankenstein.

As she traveled around Europe Sarah too was writing, keeping up her journal. Uglow describes the Losh sisters’ remarkable intelligence and sangfroid: “British women travelling abroad on their own, confident and easy, absorbing everything they saw.” They saw Lombardic churches in Pavia, Parma, and Ancona, and visited Byzantine basilicas in Ravenna, with their plain brick exteriors belying the decorative splendors awaiting the travelers within. These were inside-out buildings, revelations that were suggestive for the church of St. Mary’s. Much of what she saw on her continental travels was reworked into Losh’s own Cumbrian architectural projects. At the Vatican she noted the Fontana della Pigna, the ancient Roman fountain in the form of a pinecone flanked by two great peacocks. Nearly four meters high, it was the largest sculpted pinecone in the world.

Jenny Uglow has recently been lauded as “an influential pioneer in the art of ‘group biography.’” It would be exaggeration to claim that she invented it. For instance Noel Annan’s then groundbreaking essay “The Intellectual Aristocracy,” charting the Oxford and Cambridge family connections of the Macaulays, Arnolds, Trevelyans, Darwins, and others of the British high intelligentsia, was published in 1956. But the networks of the mid-eighteenth-century English scientist-inventors is a subject Jenny Uglow made her own in The Lunar Men (2002), which brought together James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, Josiah Wedgwood, the first industrial potter, and Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles and physician, poet, theorist of evolution. All this energetic innovation was centered in the English Midlands of the 1760s.

Her new book on Sarah Losh is comparable in scope in the emphasis it puts on scientific and politically progressive thinking in the regions further north. The male members of Sarah’s Cumbrian family were Whigs, involved with local radicals and free thinkers and with northern literary and philanthropic movements as well, for example in wide-ranging modernizing agricultural and industrial developments.

John Losh, Sarah’s father, was zealous in improving his considerable estates. He is reputed to have been the first landowner in Cumberland to import Italian rye-grass, combining it with seeds of sainfoin, lucerne, and red clover to enrich the meadows. He enlarged his herds and flocks, bringing in new breeds of sheep. His great enthusiasm was for planting trees, oaks as well as the new plantations of larches that altered the entire visual aspect of the landscape. The genial squire also had intellectual interests as a scientific amateur, collecting minerals and fossils. Fossils make a reappearance in the decorative motifs of Sarah Losh’s church.

A profounder influence on Sarah’s intellectual development was her father’s younger brother James, a lawyer and a radical, a nervy, charming, imaginative man, the friend of William Godwin and of Coleridge and Wordsworth. Southey described James Losh as “coming nearer to the ideal of a perfect man than any other person whom it has been my good fortune to know.” He took on gladly the task of educating his receptive young relation. He and Sarah read books together and they gardened. He brought his niece with him to London and to Bath and introduced her into the circle of his friends. James Losh became a leading Newcastle reformer; his statue (in a Roman toga) still stands impressively on the stairway of the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society.

A third brother, William Losh, was also based in Newcastle, running the family alkali works and iron foundry. Alkaline salts, a form of refined soda, were an essential component in the local Tyneside glassmaking, soapmaking, and textiles trades. William, a far-sighted entrepreneur and inventor, seized his opportunities, constructing a lead chamber to make sulphuric acid to speed up the process of alkali production. In 1830 his company produced 986 tons of alkali, a third of the total Tyneside output. It was largely from the alkali works that Sarah’s coming fortune would accrue. Jokingly she called herself a “soda maker.” Losh’s power of choice in controlling her own destiny, her ability to act out her imaginative visions, depended on the practical family talent for technological innovations.

Advertisement

Her ebullient, sociable father died unexpectedly in 1814. He had always tended to eat and drink too much. It emerged after his death that a young Carlisle woman had borne him an illegitimate son, a second Joseph. John’s estate was left to Sarah and Katharine equally, including their share in the Losh family’s prospering industrial enterprises. Besides alkali the Loshes were involved in the development of railways that were now greatly increasing the prosperity of the northern English cities. The brothers had been active in the plans then underway for a railway line linking Newcastle to Carlisle.

After her father’s death Sarah began building. Doggedly planning, creating, and renewing: this was to be her habitual response to her shock and grief when other people close to her died. First she and her sister set about “improving” the family house, Woodside, an old and rambling mansion, an amalgam of styles from the medieval country yeomans onward. In her grandfather’s time, Woodside had been “Georgianized,” remodeled in the then fashionable eighteenth-century neoclassical mode. Sarah and Katharine, influenced by the novels of Sir Walter Scott, with their evocations of the heroic architecture of the past, restyled the house again.

The Georgian front was now transformed to neo-Tudor, reworked in light stone and given mullioned windows with Gothic inner frames. Two heavily carved owls appear on the façade, prefiguring the gargoyles that were soon to be a feature of St. Mary’s. Inside the building three large halls and other rooms were exuberantly decorated by the sisters with trophies, armor, and weapons. The Loshes had no concept of the minimal. Woodside was an extravaganza of historicist feeling and Romantic taste.

The really interesting thing is Losh’s own practical involvement in the techniques of building that she learned from a local mason, William Hindson. Half a century before the Arts and Crafts movement, which sprang from the ideas of William Morris and his revival of long-forgotten skills, Sarah Losh was determinedly acquiring her own expertise in the handcrafts of stonework, carving, and stained glass. She learned to model in clay, equipping an outhouse for her studio and employing a local artist as her tutor. Local village craftsmen showed her how to work in wood. In a sale after her death one of the items on the inventory was her own set of woodworker’s tools.

It was also most unusual for a woman of her period to take an active part in architectural practice. Women of nineteenth-century landowning families might find and even supervise the building work on their estates but Sarah and her sister took their responsibilities much further. When it came to the building of a new village school at Wreay they designed the building and saw the project through in all its complex detail, acting as the architects and also the site managers. Losh, in whom Romantic idealism and pragmatic bossiness was usefully combined, established a workable legal and financial basis for the future of the school. Her view of architecture was a generous, profound one, the expression of her sense of connectedness with the village and the land.

In September 1833 Sarah’s much loved uncle and literary mentor James Losh died. Only the month before he had been staying at Woodside with his nieces when, as he noted in his diary, his “old friend Wordsworth,” now seeming “somewhat infirm” had come to dinner and they “passed a very pleasant and tranquil evening.” James Losh died as the result of a sudden stroke. Since traveling in Italy, Sarah had been becoming more affected by thoughts of human transience. Consciousness of time passing, of the almost geological layerings of memory, was sharpened by the sadness of her uncle James’s death.

There was worse to come. Less than two years later her sister Katharine fell seriously ill. She died in February 1835. The sisters had been so closely linked, so complementary in character, that Sarah at first felt bewildered and diminished. She responded, as Uglow puts it, “with a panic like that in ghost stories where a person loses their shadow, or looks in the mirror and sees no reflection.” Sisters were closer in the early nineteenth century. Uglow compares Losh’s numbed response to the terrible sense of abandonment experienced by Cassandra Austen in 1817 after the death of her younger sister Jane.

When Katharine died, Sarah was almost fifty. In appearance and personality she altered. She became more visibly sombre, exchanging her old bright fashionable clothes first for funereal black and later for muted shades of gray and mauve. Losh became more obdurate, a little grimmer in making her return to architecture. It was now that she conceived a succession of new buildings for her village: a small local freestone mortuary chapel on the crest of a hill near the new Wreay graveyard she was planning; a low, simple sexton’s cottage with her characteristic narrow curved arch windows; and the church of St. Mary’s, the building that became her undoubted masterpiece.

The new village church was replacing an old dilapidated chapel. Sarah cannily argued her plans through the meetings of Wreay elders and the more intimidating Bishop, Dean, and Chapter of Carlisle with promises that she would “re-edify” a building of no inherent quality, already “marred and spoilt by unskilful hands.” Her arguments gathered extra force from the fact that Miss Losh was paying for the new church. She proposed an early Saxon or modified Lombard style of building in what she called the “unpolished mode.” The late 1830s was just the time when English Church architecture was in the grip of an Anglo-Catholic medievalizing passion. Contrasts, A.W.N. Pugin’s wittily pro-Gothic architectural polemic, had been published in 1836, to be followed by his True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture in 1841, in which he argued that Gothic was the only truly religious way to build.

Sarah Losh was unaffected by the arguments for “classical Gothic of the Decorated Style” put forward by the widely influential Camden Society, pursuing her own architectural visions with a certain innate northerly contrariness. Influences for what Uglow describes rightly as her “stubbornly individual church” came from Cumbrian vernacular architecture, the local Norman churches she had known well from her childhood, and the Lombardic styles she remembered from her travels in Italy with Katharine—an eclectic, instinctive, and highly personal mix. Her ideas for the church drew on her scholarly interests in classical, Egyptian, and Eastern beliefs. She combined this with her love of the pure, simple, and rustic. “Rustic” was a word dear to Wordsworth’s heart as well.

Externally the church has great solidity and dignity. It has the aspect of a local fellside barn. This simple rural structure is embellished by rich carvings around the doors and windows, thick with lotus flowers and pinecones, insects, birds, and fossils, stone specimens of nature all packed in together with a wild enthusiasm that is wonderfully strange. But the true originality of St. Mary’s church lies in the interior, the combination of rectangular nave with chancel apse. Here Sarah, in 1840, quite amazingly predicts the Byzantine church revival of circa 1900 by such English Arts and Crafts architects as Sidney Barnsley, whose church of St. Sophia at Lower Kingswood, Surrey, has a similarly bold eclecticism.

In Sarah Losh’s mise-en-scène every detail has its meaning. As Nikolaus Pevsner has reminded us, these symbolic carvings, based on Losh’s conceptions, are totally original. In architectural history they “have no parallel at all.” Her lotus flowers stand for creation. Pomegranates bear the message of regeneration. Her pinecones, so ubiquitous all around the chapel, symbolize eternal life. They recall her own childhood fascination with the cones of the Scots pines on the fellsides, changing shape and color as they aged, opening and closing according to the dampness and dryness of the weather.

Besides this local meaning, pinecones were symbolic to the Romans, the Egyptians, and also to the Masons. They appear in the decoration of masonic halls. Such layerings of significance, unexpected correlations of image and belief, delighted Sarah Losh and gave her architecture its density of character. In the mausoleum later built by Sarah to commemorate her sister, the white marble statue of Katharine contemplates a pinecone held balanced on her lap.

Her method of building by direct local labor has many obvious parallels with John Ruskin’s pleading for a return to the structures of the medieval craft guilds with their personal involvement in the perfecting of the work. But Losh’s practice predates Ruskin’s theorizing. His influential treatise The Stones of Venice, the book that seemed to William Morris “to point out a new road on which the world should travel,” was not published until 1851–1853. Here again Sarah Losh, building St. Mary’s in the early 1840s, was indeed a pioneer.

The Wreay villagers themselves were involved in the construction, village day laborers working alongside local builders. Through one busy summer of church building, neighborhood farmers gave their labor free, lending their carts in between harvesting to haul the stone and timber. Sarah’s own gardener Robert Donald carved the complex gourd and vine around the door frame. Another craftsman, John Scott, a crippled man from Dalston, carved the lectern with a flying stork and eagle suspended above the hard black bog oak pulpit. The stained glass windows were provided by the combination of a local firm and William Wailes of Newcastle, a craftsman in stained glass who would later become famous for his work. Wailes was a traditionalist in method. The beauty of St. Mary’s is its artisan workmanship, skilled but unpretentious, rooted in its own locality.

And working alongside the craftsmen she had hired was Sarah Losh herself, an indomitable figure. She molded the clay models for the natural history carvings for St. Mary’s, showing the craftsmen how to translate her imagined plants and animals to stone. Working in collaboration with her artist cousin William Septimus, she personally carved the church’s lotus flower candlesticks in pink alabaster and created the elaborate alabaster font.

Her talent and determination were undoubted. But how good a case is made in Jenny Uglow’s book for regarding her as an unfairly forgotten “architectural genius of the nineteenth century”? She had no direct architectural influence. She founded no school of visionary female architects. In Britain her nearest counterpart in sheer creative fervor is Mary Watts, widow of the great Victorian painter G.F. Watts, whose Mortuary Chapel of 1896 designed in honor of her husband has a similar wealth of extraordinary detail. In the US the nearest parallel I know of would be a male one, Bernard Maybeck’s First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley, California. Sarah Losh’s true importance, as Uglow makes clear in this affectionate and penetrating study, was that in her brilliant architectural work she was one of a kind.