The Republican Party may have come off very poorly indeed to a large number of Americans during the October debacle over the shutdown of the government and the debt limit. In more than one poll, the party’s popularity hit record lows, with approval ratings down in the 20s. However, it didn’t take long after the fiasco ended for many observers to note that while the party may have absorbed a political black eye, it was more able to exert power over economic policy than most Americans, even most Washingtonians, realized. As the National Journal’s Michael Hirsh, a keen spectator of the goings-on in the capital, wrote in an October 19 column, while it was true that, at the eleventh hour, the Republicans lost the fight over Obamacare and “surrendered” on every major point of contention between them and Democrats, they still remained in control of the country’s fiscal agenda.

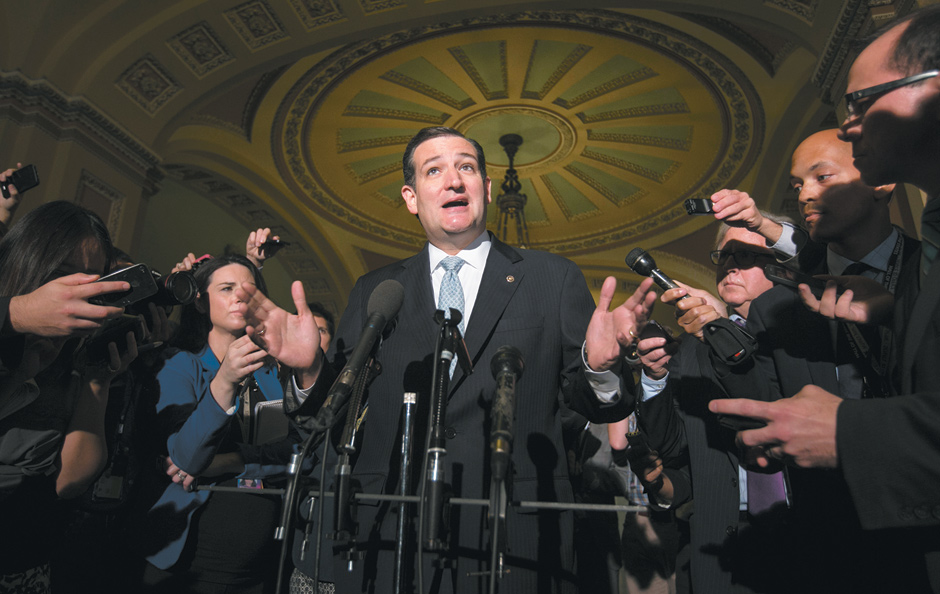

Yes, the price the GOP is paying for Senator Ted Cruz and for the extremist tactics of the Tea Party is and will continue to be real. And yes, we now see an internecine struggle brewing among Republicans, which will likely culminate during the 2016 presidential nominating process and may someday, it’s no longer crazy to believe, split the party in two. And certainly, the fortnight was a humiliating one for House Speaker John Boehner, exposed as probably the weakest House leader in the modern history of the country. But all that said, fiscally, the GOP remains in the driver’s seat. As Hirsh put it:

Indeed, going back to 2010, when the GOP took control of the House, nearly everything has gone more or less the Republicans’ way on fiscal issues—they got the Bush tax cuts locked in (except on the highest earners), government spending reduced, and the sequester imposed.

Despite Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s efforts to renegotiate the sequester, Obama in effect has conceded he can live with its across-the-board spending levels: In September, the White House announced it would approve a House Republican spending bill that kept the government funded at current levels as long as language that would defund Obamacare was stripped out.1

Of the facts Hirsh cites to support his point, it’s the “sequester” that is decisive. This consists of the mandated, across-the-board spending cuts that were agreed to in August 2011 as part of a deal to avert default then and that were imposed last spring. Republicans, especially Tea Party Republicans, had pushed for these lowered spending levels, and Democrats had resisted them strongly. That deal remains Barack Obama’s nadir as president. Focused on reelection, he and his advisers thought they were impressing swing voters by demonstrating a willingness to compromise. But polls at the time showed that really wasn’t the case—swing voters just thought the president looked weak. And Democrats on Capitol Hill hated the cuts.

But they were law, and they became, to use one of those phrases one hears in Washington far more than anywhere else, “baked in the cake.” They mean, to take one of many examples, that $11 billion have been stripped from Medicare. The recent compromise to end the government shutdown, the one that Congress passed and Obama signed just after midnight on the morning of October 17, funds the federal government only at the current sequestration-imposed levels. Sequestration is a big part of the reason that another long-sought goal of Tea Party members and other fiscal conservatives has been met. For the first time since the early 1950s, federal spending has declined for two consecutive years.

Under the October agreement, that reduced funding runs until January 15, by which deadline Congress and the president have to reach another deal, or the government could shut down all over again. The debt limit was extended until February 7, but with various accounting gimmicks the Treasury Department is permitted to use under law, that period can be dragged out, so the next debt-limit fight shouldn’t hit until April.

What will happen in January? In Washington one rarely goes wrong in expecting the worst. And sure enough, the general wagering right now among the Washington cognoscenti is that we are staring at yet another stalemate. But there are a few reasons to think that Obama and the Democrats can reverse the recent surge of Republican power to some extent and win two modest but important victories. First, they could get the sequester lifted and increase spending in some categories again. Second, it now seems that entitlement programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, which Obama has shown a willingness to cut in the past, have a good chance to emerge unscathed. But to notch even these wins, Obama and the Democrats will have to stand their ground as resolutely as they did in October, and that may prove more difficult when the debate is not about the Republicans trying to defund an existing law but the more prosaic question of how much money will be budgeted.

Advertisement

That the episode involving the government shutdown and the debt limit was a fiasco for the Republican Party is something no one—well, no one this side of Ted Cruz—seriously disputes. Cruz himself told ABC News’s Jonathan Karl that of course he would do the same thing again “to stop the train wreck that is Obamacare.” And it’s not as if no one saw the fiasco coming, either. As October 1 approached, numerous Republican officeholders warned that this was neither the time nor the place to refight the battle over health care.

Democrats and liberals should not, therefore, expect that the same circumstances or the same chances for victory will present themselves again in January. It is true that senators are autonomous actors today and that Cruz is, to say the least, unpredictable. But he has made his point, and he has won what he presumably set out to win: the allegiances of Tea Party voters across the country, and particularly in Iowa, which he visited the last weekend of October. He knows that the Affordable Care Act won’t be defunded legislatively as long as Obama is president and the Democrats control the Senate, so come January, he can simply rant about how his hands remain tied by the quislings and invertebrates populating the Senate Republican caucus. His partisans are likely to accept that.

In other words, come the next deadline, the Republicans are unlikely to hand the Democrats the Christmas gift of embarking on so quixotic and divisive a project as again trying to defund Obamacare. The next fight will be about money—about the sequester. And on this issue, as noted, Republicans have been getting their way in imposing cuts in spending and other policies even while appearing to lose politically. The most notable example of this came during the “fiscal cliff” negotiations in January 2013, when a combination of fiscal deadlines, the Bush tax-cut expiration, and the debt limit forced Congress to act.

First, Obama won a small tax increase then—a 4.6 percent hike in the top marginal rate on dollars earned above $450,000 (per household). That, combined with a general air of panic in some Republican circles that they would be blamed if the United States defaulted, gave that last-minute deal the appearance of being a win for Obama. But in fact the tax increase he secured was much smaller than he’d sought (he wanted that increase on dollars earned above $250,000), and the sequestration cuts kicked in on March 1. The revenue from the fiscal cliff deal of last January is set to amount to $617 billion over ten years; the sequestration cuts, $1.5 trillion. So it should be clear who won that round.

The sequestration cuts, of course, were designed not to happen, with the idea back in 2011 being that they were so severe and arbitrary that surely Congress would act to prevent them. But Congress did not do so, and so we’ve seen around $85 billion in sequestration-based cuts made in 2013. They include $43 billion in defense, $26 billion in domestic discretionary programs—law enforcement, environmental protection, etc.—$11 billion in Medicare, and $5 billion in “other.” Under the law, the cuts are scheduled to amount to around $109 billion for 2014 and for every year thereafter through 2021.

Broken down further, the 2013 cuts include $17.1 billion in military operations across the service branches; $1.6 billion for the National Institutes of Health; $595 million for border security; $928 million for FEMA disaster relief; $400 million for Head Start; and much more.2 Even in Washington, that’s real money. Extensive reporting—notably in The Huffington Post, which ran an interesting series, but really everywhere—has detailed the cuts’ impact on cities and towns across the country. A recent New York Times report gave a good sense of how departments and agencies are no longer able to shift dollars around to lessen their effects:

The fiscal year that ended Sept. 30 was an exercise in creative accounting, nest-egg robbing and seed-corn gobbling. Sequestration cut $1.75 billion from the Navy’s shipbuilding program, so the Navy scrounged nearly $1 billion from unspent money from previous years and scrapped contracts for a destroyer, a submarine and a planned overhaul of aircraft carriers, according to the staff of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. In January, an additional $1.6 billion must be extracted from the same account, and with no coins under the cushions, every ship in the fleet is expected to be affected.3

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has made it clear that his goal between now and January is to end the sequester cuts. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said the same shortly after the October 17 deal, arguing that the cuts reduce the real gross domestic product by 1.2 percent.

Advertisement

Even some Republicans have indicated that they are open to this. In that same New York Times article, House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, the House GOP’s leader on these issues, not normally known for a willingness to find common ground with Democrats, said: “We agree there are smarter ways to cut spending.”

Ryan is the chief Republican negotiator in a round of talks with his Democratic counterpart Senator Patty Murray of Washington, and they are supposed to present their ideas by mid-December. But it’s not clear what “we” Ryan is speaking for. Getting majorities of Republicans in the House and Senate to agree to drop or seriously modify sequestration still seems a big challenge. Most Republicans in both houses continue to think the federal budget is a sinkhole of waste, fraud, and excess. To them, the cutting has just barely begun.

A deal ending or at least easing sequestration could conceivably pass the Senate now. The October compromise on the debt limit sailed through by 81–18. The immigration reform bill, another recent case in which some Republicans compromised, cleared the Senate in late June by a vote of 68–32. Among the forty-five Republicans, only twenty-seven voted to end the government shutdown, and fourteen voted for the immigration bill. Those two votes, I think, give us a general range of the number of Republican senators who might be willing to play ball on a new and less draconian budget bill.

The House is a tougher case. The October compromise won the support of just 87 Republicans, while 144 opposed it. And the House of course has not taken up immigration reform, so there is no vote on that matter to provide us a with a sense of Republican flexibility.4 Getting a bill to end or ease sequestration through the House, then, seems a difficult prospect. What leverage do Obama, Reid, Nancy Pelosi, and amenable Republicans have?

The answer is the looming defense cuts. Again, back in 2011, the thinking was that Republicans would agree to avoid sequester’s imposition because, while they’re happy to see domestic programs chopped, they would want to protect the Pentagon. This assumption turned out to be wrong in early 2013. But there is some reason to believe—no one really knows how much—that this time, things might be different.

The $109 billion in cuts that sequestration imposes in 2014 were intended to be shared equally by defense and domestic programs. But because the fiscal cliff deal took a couple of steps to spare defense in 2013, the 2014 cuts will now tilt in the direction of hitting the Pentagon harder. The net result is that domestic programs in 2014 will be funded at almost exactly the same level as 2013 ($469 billion as opposed to $468 billion), while defense spending will actually fall in real dollars by $20 billion ($518 billion to $498 billion).

These cuts will be felt across the country. In every congressional district in America, numerous defense contracts are in place at any given moment. The most comprehensive study of this I’ve ever seen was completed by the conservative Center for Security Policy, which in August 2012 produced lists of extant Pentagon contracts and their dollar amounts in every district.5 The results are a revelation. In a typical district, more than one hundred defense contracts were in force; often, two hundred. They ranged from a few thousand dollars up to $5 million or $10 million or $20 million, or sometimes more.

Some of these employers are among the largest and most important in any given district. Defense spending plunged a hefty 22 percent in the fourth quarter of last year. Under the impending sequester scenario, more cuts like that are surely in store.

To some Tea Party people, this won’t matter: they believe they were elected to slash spending, and that is what they are going to do, the Pentagon included. But it’s not unreasonable to think that some of those 144 who opposed the shutdown deal might prove susceptible to pressure from major defense contractors and employers in their districts. It’s also a plausible thought that John Boehner, so thoroughly mocked after being led around by the nose by his caucus’s extremists, won’t let that happen again and will make an attempt, for a change, to govern. His abject admission to Obama after the shutdown—“I got overrun”—will be the three words his speakership is remembered by, unless he does something dramatic between now and what a number of observers expect will be his retirement next year.

Lifting the sequester will be difficult, but there’s another bullet that it now appears can be dodged, at least before the midterm elections: entitlement cuts.

No sooner was the deal consummated in October than my inbox started filling up with messages from Fix the Debt, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, and similar deficit-focused groups announcing that now that sanity had been restored to Washington, it was high time to move ahead with the crucial work of “getting our fiscal house in order,” as it’s often put, once and for all. Getting our fiscal house in order means a few things, not all of them objectionable; but more than anything else, it means cutting Social Security and Medicare. This is the great goal and desire of a debt-obsessed center that includes Pete Peterson, Alan Simpson, and Erskine Bowles (the cochairs of President Obama’s 2010 commission), The Washington Post editorial board, Paul Ryan and many other Republican legislators, a handful of centrist Democratic ones, and assorted scholars and think-tankers around the capital.

Cuts in entitlements would be the centerpiece of any “grand bargain” struck by the two sides, which is why—if, say, you watch MSNBC, the liberals’ cable channel—you see some liberals shudder visibly at the very mention of the phrase. Obama has been open to grand bargains in the past.

But Harry Reid has so far killed the prospects of such an idea. Reid impressed observers in October more than he probably ever has by holding firm to the principle that the Democrats would simply not negotiate with the bazooka of government shutdown aimed at their heads, and by keeping his caucus unified on that point. The week after the government reopened, Nevada Public Radio asked Reid about a grand bargain: “That’s all happy talk. I would hope that were the case but we’re not going to have a grand bargain in the near future.”

The same day, Paul Ryan agreed: “If we focus on some big, grand bargain then we’re going to focus on our differences, and both sides are going to require that the other side compromises some core principle, and then we’ll get nothing done.” These were fascinating words coming from Ryan, who has had his sights on cutting Medicare for years.

Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid will need to be addressed at some point. As baby boomers retire, the programs will consume 14 percent of GDP twenty-five years from now, according to a September Congressional Budget Office report. Liberals who wish to hold the line on these programs (including paying Social Security to the very rich) might also remember that higher spending on them would probably leave less money for the kinds of domestic discretionary programs that they also wish to see supported—environmental protection, public investments in infrastructure, aid for children and students, and civil rights enforcement, to mention only a few.

But Democrats would be unwise to rush into a negotiation on these matters in the quasi-extortionate climate Republicans have created—especially considering that the GOP still won’t give an inch on raising needed revenues. So the best possible outcome for January is a “petite bargain,” built chiefly around a lifting of the sequester that will allow agencies to budget more rationally. The Republican position might be: we will lift the sequester for defense only. Democrats will again have to hold firm in opposition and hope that public opinion again lands on their side in sustaining basic notions of fairness, which I would expect it will.

Looming over all these questions politically is the future of the Tea Party, and where the Republicans go from here. The Tea Party base has so terrified Republican lawmakers since 2009 that they have in essence listened only to that wing of the party. As I observed in a column in The Daily Beast this October, one week after the shutdown, about half of Republicans in one poll disapproved of how the Republican Party was handling the negotiations.6 That half of the Republicans—millions of people—have effectively had very little representation in Washington during the Obama era.

This is starting to change. For the first time, an articulate dissenting group has been conjured into existence, Defending Main Street, designed to finance primary campaigns against Tea Party incumbents. Former Ohio Congressman Steve LaTourette, a moderate-to-conservative legislator in his day but not a Tea Partier, spoke of his plans in the kind of aggressive tone we associate with his adversaries: “Hopefully we’ll go into eight to ten races and beat the snot out of them.” In addition, Tom Donohue of the US Chamber of Commerce has said that the chamber will finance anti–Tea Party primary challengers. The chamber is on the whole a conservative organization, but it does support immigration reform and spending on infrastructure, and it and other business lobbies fret that Republican legislators no longer fear them. And Karl Rove and his Crossroads GPS group will join the battle on the “Main Street” side as well.

Across the scrimmage line, Ted Cruz and Sarah Palin and others are encouraging Tea Party challenges in order to get rid of a few of the more traditional conservative incumbents.7 So far, five such incumbents will face right-wing challengers next year: Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell (already trading some nasty punches with Matt Bevin, a wealthy bell manufacturer), South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham (a “community organizer for the Muslim Brotherhood,” according to one opponent), Tennessee’s Lamar Alexander, Kansas’s Pat Roberts, and Mississippi’s Thad Cochran. Liz Cheney, the former vice-president’s daughter, is challenging Mike Enzi, the GOP incumbent in Wyoming, and trying to wedge herself into the Tea Party template as well. Other challenges will surely materialize before the filing deadlines approach.

Lines are being drawn, and sides taken, even among the governors, usually immune to some extent from these Potomac fevers. Florida’s Rick Scott is pro–Tea Party, Ohio’s John Kasich is against. Palin, the ex-governor, has found a way to remain in the vanguard of the Tea Party movement. But the lead character in this drama is clearly Ted Cruz. One has to remind oneself sometimes that he is still in his first year as a senator. His skills as a demagogue and his instincts for getting attention, arousing his base, and traducing liberal sensibilities are unrivaled. He has been seen as a slicker and more educated version of Joe McCarthy, not without cause; and he even looks a little like him, in the way his eyes slope downward from the top of his nose.

The midterm elections will in all likelihood shape up as a referendum within the GOP on whether it wants to follow Cruz or reject him. Immediately after them, the presidential campaign, or at least the precampaign jockeying, will begin. Future budget fights, the shape of Obama’s final two years, indeed the condition of the economy, will turn to a considerable extent on whether the Tea Party movement shrivels or grows—whether old-guard Republicans have the fortitude to cage the beast they’ve been happy to see prowling the landscape wreaking havoc, until it started wreaking some on them.

This Issue

December 5, 2013

Man vs. Corpse

Adventures in a Silver Cloud

-

1

See Michael Hirsh, “Republicans Lost the Shutdown Battle, But They’re Winning the Fiscal War,” National Journal, October 19, 2013. ↩

-

2

See Dylan Matthews, “The Sequester: Absolutely Everything You Could Possibly Need to Know, in One FAQ,” The Washington Post, February 20, 2013. ↩

-

3

See Jonathan Weisman, “After Year of Working Around Federal Cuts, Agencies Face Fewer Options,” The New York Times, October 26, 2013. ↩

-

4

By the way, on immigration: if the House fails to act this calendar year, as seems likely, the Senate vote is in essence voided, and it’s back to square one. ↩

-

5

To peruse these fascinating spreadsheets for yourself, go to www.forthecommondefense.org/districts/. ↩

-

6

See “No Country for Old Moderates,” The Daily Beast, October 24, 2013. ↩

-

7

It is still a category error to call practically anyone in the GOP a moderate, as some press reports do. You can count the truly moderate Republicans on Capitol Hill on one hand. ↩