Vladimir Nabokov was eighteen when the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 made his wealthy family’s continued residence in Petrograd (as St. Petersburg was renamed at the start of World War I) impossible. They fled first to the Crimea and then, in 1919, to London. The following year they settled in Berlin, where in 1922 Nabokov’s father was assassinated, more by accident than design, by extreme right-wing Russian monarchists: they were attempting to kill another Russian émigré politician, Paul Milyukov. V.D. Nabokov bravely seized and disarmed one of the gunmen, and pinned him down, but was then shot three times by the second.

In a poem called “Easter” published just a few weeks after this disaster, the twenty-two-year-old Nabokov interprets the arrival of spring as portending some kind of resurrection of his father: “Rise again,” each “golden thaw-drop” seems to sing, “blossom”; “you are in this refrain,/you’re in this splendor, you’re alive!…” Some forty years later he would allude to the ghastly manner of his father’s demise in a more characteristically Nabokovian way: the day on which Pale Fire’s John Shade is killed by mistake in another botched assassination attempt is July 21, Nabokov senior’s birthday.

V.D. Nabokov was not the only member of the family to fall victim to the chaos of the times. Vladimir’s brother Sergey Nabokov was one year younger than him, but of a very different temperament; shy, stuttering, gay, musically gifted, a Catholic convert, Sergey spent much of his exile in Paris, where he got to know Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, and Pavel Tchelitchew, with whom he shared an apartment for a while. His long-term partner was a wealthy Austrian called Hermann Thieme. While the rise of the Nazis drove Vladimir, whose wife Véra was Jewish, to embark for America with their young son Dimitri in May 1940, shortly before the fall of Paris, Sergey and Hermann Thieme responded, somewhat bizarrely, by moving east to Berlin. There they were arrested for homosexual offenses; Hermann was freed but forced to join the German army in Africa, while Sergey spent five months in jail. On his release he moved to Prague, where he set about openly denouncing the Nazis and Hitler; he was soon informed upon, arrested again, and in the spring of 1944 dispatched to Neuengamme concentration camp, on the outskirts of Hamburg. He did well there, in that he lasted ten months, whereas the average life expectancy was twelve weeks. Sergey was forty-four when he died, the age of Pale Fire’s Charles Kinbote, another awkward homosexual exile, who is also hounded and harried, or so he’d have us believe, by a ruthless totalitarian regime that has come violently to power.

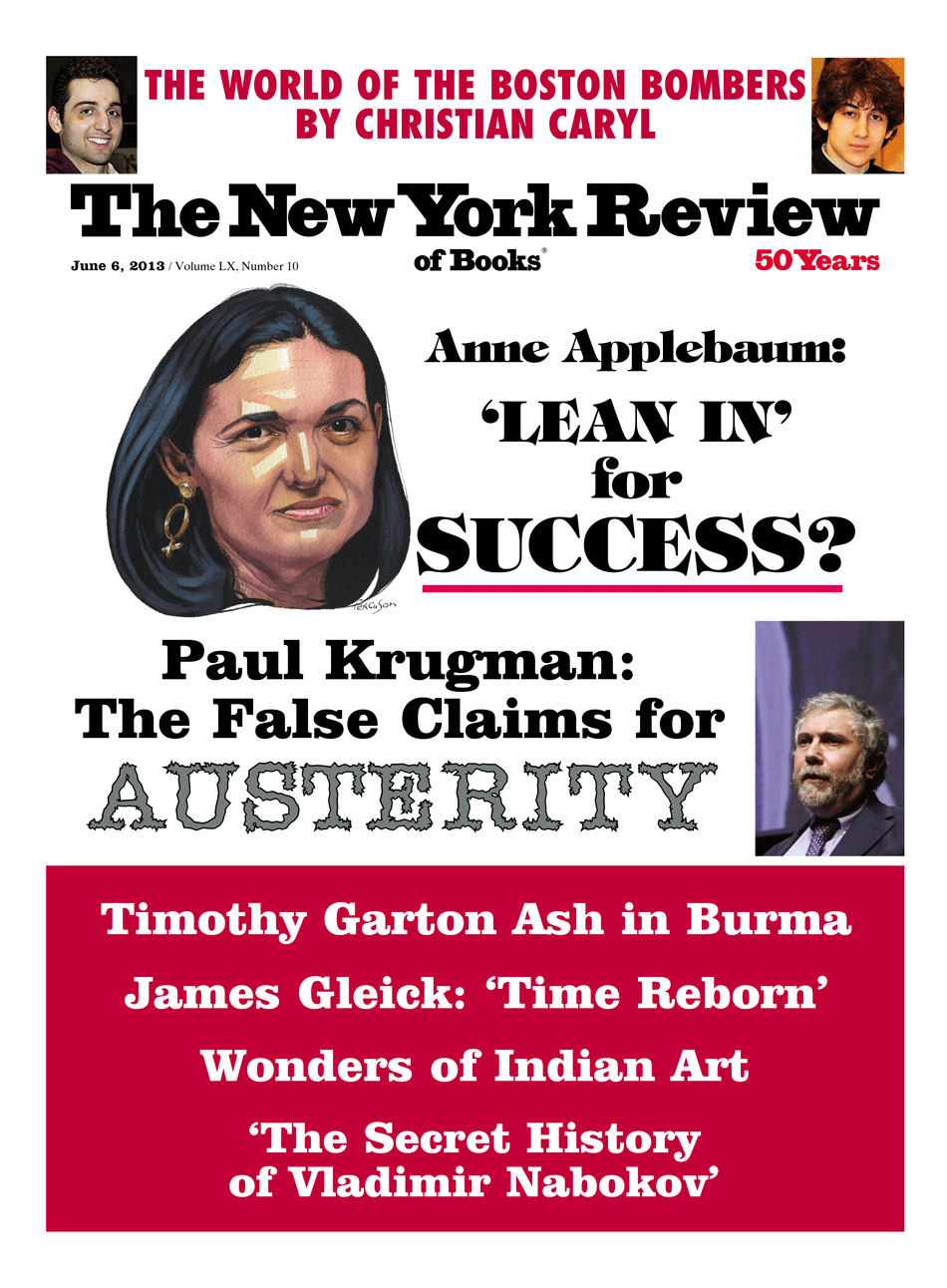

Why, Andrea Pitzer asks in her provocatively titled The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, did the great novelist allude only in such oblique, ludic terms both to his own personal losses and to the historical cataclysms that caused them? Cataclysms that also meant that he could never return to a country he missed acutely, and forced upon him a precarious émigré life in England, Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, and then America, where at last he struck gold with Lolita, so much gold indeed that he was able to spend the last fifteen years of his life in the luxurious Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland.

There are numerous ways of approaching this question. The most reassuring response might pivot around Nabokov’s famous definition of his art in his afterword to the all-conquering Lolita, which has steadily sold at the average rate of a million copies a year, and is surely the most indisputably canonical novel in English of the postwar era:

For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm. There are not many such books. All the rest is either topical trash or what some call the Literature of Ideas, which very often is topical trash….

Any attempt to write directly about political events or the “sweep of history,” to borrow a phrase from the jacket copy of any number of blockbuster epics, will be mired in the cliché and sentiment that Nabokov deplored in novels such as Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago (one of his many bêtes noires); the artist’s truest and most valuable way of resisting totalitarian modes of thought is to assert his or her independence as thoroughly and, in Nabokov’s case, as spectacularly as possible. He conceived of writing as a chess match with a razor-keen opponent always looking to predict his next move, and joy and triumph lay in outwitting that reader’s assumptions, and thereby stimulating “curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy.”

Advertisement

The comprehensive cleverness of such a relation with the reader, both in theory and on the page—in his best fiction anyway—means that one can’t even begin to formulate the less reassuring answers without finding oneself in the role of John Ray Jr., the gloriously crass psychologist who introduces Humbert Humbert’s memoir, and pronounces its author “a shining example of moral leprosy.” “Oh, my Lolita, I have only words to play with!” Humbert plangently declares after some bravura puns and rhymes (“Quine the Swine. Guilty of killing Quilty”) at the end of Chapter 8 of Part I of Lolita; but in a book, as both he and his creator know, words are everything.

In the same afterword, Nabokov described how the “initial shiver of inspiration” that grew into Lolita was “prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes, who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.” Humbert, this anecdote seems to be cautioning us, sees and presents only the bars of his pedophilia, an aspect of which is his need to confide it to us in the infinitely cunning apologia pro sua vita that he writes in his prison cell while awaiting trial for the murder of Quilty; therefore even the startling and heartrending glimpses into Lolita’s experience—his recording her “sobs in the night—every night, every night—the moment I feigned sleep”—should be read as carefully orchestrated bids for the sympathy of the reader, rather than moments when Humbert “sincerely” (and how Nabokov loathed the concept of sincerity in fiction!) sees beyond the bars of his cage.

Hence his every instance of self-criticism—as when he tells us he chose the pseudonym Humbert Humbert because it “expresses the nastiness best,” or laments as the “hopelessly poignant thing” not the absence of Lolita from his side, but the absence of her voice from the musical hubbub of voices he overhears in a playground—extends the fiction of repentance, and encourages us to forgive his monstrousness. The golden-tongued Humbert, one must always remember, is possibly the greatest rhetorician since Milton’s equally persuasive and dangerous Satan.

Nabokov’s conception of the artist as quasi-divine inventor means that—as is the case with one of his great heroes, James Joyce—critics tend to find themselves in the role of enchanted hunters looking for clues and connections, spotting recondite allusions, praising the novels’ elaborate artistry, or elucidating labyrinthine patterns. It would take a bold critic to read such a dazzling, seemingly omniscient, and utterly self-conscious oeuvre as depicting the bars of Nabokov’s own cage. Andrea Pitzer doesn’t, perhaps, go quite that far, but she does invite us to step back a little and ponder the oddness of the relationship Nabokov’s writings create between the fictive and the historical.

She does this by contrasting him with another Russian writer much lauded in the West, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Shortly after Solzhenitsyn was deported from the Soviet Union in 1974, he arranged to meet Nabokov and his wife for lunch at the Montreux Palace Hotel. Pitzer’s opening chapter describes the Nabokovs awaiting the arrival of the Soviet Union’s most famous dissident in a private dining room of their hotel. While their personalities and experiences could hardly have been more different, the two writers’ shared hatred of communism would surely have created plenty of common ground for discussion. In the event, Solzhenitsyn never showed up, possibly fearing a put-down from the aristocratic Nabokovs, who indeed thought little of Solzhenitsyn as a writer. Pitzer, however, makes deft use of this aborted encounter, tracing the different paths each had taken to literary stardom: Solzhenitsyn in the Gulag, Nabokov in Cambridge, Berlin, and Paris, then at Wellesley and Cornell; the one compiling a vast and irrefutable indictment of Soviet abuses, the other studiously avoiding direct treatment of this harrowing topic in his fiction.

Animating Pitzer’s retelling of Nabokov’s life, however, is her contention that Nabokov did in fact weave various explicit references to historical events into his fiction, and indeed that “behind the art-for-art’s sake façade that Nabokov both cultivated and rejected, he was busy detailing the horrors of his era and attending to the destructive power of the Gulag and the Holocaust in one way or another across four decades of his career.” Dazzled by Nabokov’s “linguistic pyrotechnics,” readers and critics have simply overlooked these details. “This is a story,” she proclaims, “as much about the world around the writer as the writer himself, and a look at how epic events and family history made their way, unseen, into extraordinary literature.” As such quotations demonstrate, Pitzer has a tendency to write in a manner that would make her fastidious subject’s toes curl, but then why should Nabokovians attempt to emulate the master? Although Pitzer often rather overstates her case, she has done much exemplary primary research, and this book forces one to consider several fascinating quandaries presented by Lolita and Pale Fire.

Advertisement

The first of these is: Is Humbert Humbert Jewish? The word “Jew” and its cognates never occur in Lolita, but it is almost said on a number of occasions. Several characters assume Humbert is Jewish. John Farlow, at the end of Chapter 18, Part I, complains of the fact that Ramsdale has too many Italian tradespeople, adding, “but on the other hand we are still spared—,” at which his wife Jean, suspecting that Humbert is Jewish and not wanting him to be offended, tactfully interrupts her blundering spouse. (In the Russian translation that Nabokov made of the book, John clearly begins to say the word “kikes.”)

A classmate of Lolita’s, Irving Flashman—originally Fleischman?—is pitied by Humbert for reasons initially obscure, but explained by Nabokov to the book’s annotator, Alfred Appel Jr.: “Poor Irving, he is the only Jew among all those Gentiles. Humbert identifies with the persecuted.” Humbert, and Nabokov, have much grim fun with the anti-Semitic policy of the hotel the Enchanted Hunters, whose notepaper declares, NEAR CHURCHES and NO DOGS, code for “Gentiles only”: perhaps, Humbert muses, the “silky cocker spaniel” Lolita had petted on their visit to the hotel had been “a baptized one.” And when Humbert’s name on a postcard requesting a room at the hotel is misread as the Jewish-sounding Professor Hamburg, he receives a “prompt expression of regret in reply. They were full up.”

These references, along with a number of others, were all pointed out by Alfred Appel Jr. in his pioneering annotated edition of Lolita of 1970, where he also notes the importance to the conception of Lolita of Agasfer (1923), an early verse drama by Nabokov based on the story of the Wandering Jew. Aggregating all these references, Pitzer—and here she stakes her claim to an original reading of the book—argues that what Nabokov is actually doing in Lolita is deliberately drawing on all manner of anti-Semitic propaganda, from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion to Nazi caricatures of the Jewish “type,” to create in Humbert Humbert the anti-Semitic cliché of legend, rather as, say, Chaucer draws on medieval misogynist writings to create in the figure of the Wife of Bath the archetypal shrew of his male audience’s nightmares. Humbert combines

revolutionary politics, an easy income, cosmopolitan intellectualism, sexual perversion, and a truly monstrous sin—in Nabokov’s rendering, not blasphemy against Christ but the relentless, ongoing molestation of a child.

Here, then, is another reason for forgiving him: he is “a war refugee fleeing Europe,” a victim “broken by history,” a member of a persecuted race into whose dreams explicit images from the death camps erupt—“the brown wigs of tragic old women who had just been gassed.”

His crimes, Pitzer argues, “are not only the cause of his persecution in the world; they are, in some measure, the result.” “Those to whom evil is done,” as Auden succinctly put it in his poem on the outbreak of World War II, “September 1, 1939,” “do evil in return.”

Nabokov had trouble enough getting the book published as it was; to have made Humbert explicitly Jewish as details of the Holocaust were filtering into the public domain, even if he’d wanted to, might well have put it decisively beyond the pale. And so fiendishly self-serving and skillful is Humbert’s storytelling that it’s surely not impossible that, in his surreptitious way, he is subliminally playing the Jewish card, so to speak, without actually being entitled to it, a rhetorical move dramatically made by Sylvia Plath in “Daddy” a few years later: “Chuffing me off like a Jew./A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen./I began to talk like a Jew./I think I may well be a Jew.”

Certainly Jewishness lurks in the hinterland of the novel, and anti-Semitism in a number of its nooks and crannies. Few readers, I’d guess, would agree with Pitzer’s categorical definition of Humbert as Jewish—or surely that should be half-Jewish since we are told at the book’s opening that his mother was an English girl and the grand-daughter of two Dorset parsons—but Pitzer’s excavation of this particular strata of the book’s references is both illuminating and unsettling. The Jewish aura, to put it no more strongly than that, that occasionally cloaks Humbert is yet another instance of his sinister ability to infiltrate and contaminate the literatures, languages, and cultures that he appropriates.

The other major plum in Pitzer’s pudding derives from her research into the history of Nova Zembla, an archipelago of islands in the Russian Arctic. Charles Kinbote of Pale Fire claims to be the deposed king of a country called Zembla that shares a border with Russia. Like his creator, he finds refuge in America, teaching at Wordsmith University in the Appalachians; there he meets a Frostian poet called John Shade, to whom he confides details of his former life in the hope that Shade will incorporate them into the poem on which he is at work.

Pale Fire consists of Shade’s 999-line poem—called “Pale Fire”—and Kinbote’s elaborate commentary on it, which he uses to recount his reign in Zembla as Charles II—also known as Charles the Beloved—as well as the coup that unseated him, his imprisonment, his escape, and the movements of the killer, one Jakob Gradus, sent by the new regime in Zembla to assassinate him—only Gradus ends up killing John Shade by mistake. What a very peculiar novel Pale Fire is! Eventually we learn that Shade was indeed shot by mistake, like Nabokov’s father; the killer, however, was one Jack Grey, an escapee from an asylum seeking revenge on the man who put him behind bars, Judge Goldsworth (Wordsmith—geddit?), whose house Kinbote is renting while the judge is on sabbatical in England.

Alexander Pope is normally seen as the literary source for Zembla: in his “Essay on Man” Pope wonders whether “th’extreme of Vice” can ever be fixed (a question particularly pertinent in the post-Holocaust era), and offers the following geographical analogy:

Ask where’s the north?—at York ’tis on the Tweed;

In Scotland at the Orcades; and there

At Greenland, Zembla, or the Lord knows where.

But as early as a review of the book by Mary McCarthy in The New Republic in 1962, the possible link to the real Nova Zembla was noted. Pitzer pursues McCarthy’s hint, recounting the history of the islands from the terrible winter that the Dutch explorer William Barents and his crew had to spend on a Nova Zemblan island in 1596–1597, after their ship got trapped in the ice, to the archipelago’s use as a nuclear weapons testing site by the Soviets in the late Fifties and early Sixties, when Nabokov was at work on Pale Fire.

So inhospitable is Nova Zembla that no one has ever settled there, but rumors of a labor camp established on one of its islands circulated among prisoners sent to work in the gulags of the Arctic Circle: as an American called John Noble who ended up in one such camp, Vorkuta, recounted, Nova Zembla hovered as a threatened final destination for detainees who caused trouble: it was the place “from which there is no return.”

Is Kinbote, then, a victim of a Soviet labor camp, as Humbert, in Pitzer’s argument, is of the Holocaust? Does Pale Fire, in its oblique way, bear witness to the atrocities described in such detail by Solzenhitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago? Or perhaps, rather, the question should be: Why did Nabokov filter in the allusions that furnish Pitzer with her readings of Lolita and Pale Fire in a manner so nuanced as to make them almost invisible? The answer, I suppose, would be that, in both cases, Pitzer’s interpretation makes Humbert and Kinbote rather less interesting as characters, easier to place, more comprehensible, and in turn pushes the novels in which they feature too close for their creator’s comfort to the realm of “topical trash” excoriated in the afterword to Lolita. A “secret history” implies a history that can be uncovered and then understood; Nabokov, for all his teasing and games-playing and breathtaking ingenuity, wanted more, much more, from his art than that. And that he couldn’t always achieve it anyone who has tried to read Ada will know.

Kinbote, Humbert, Pnin, and Nabokov all came to America to escape the revolutions and wars of Europe, and all found themselves berths in the American university system. One couldn’t argue, then, that Nabokov was not inviting comparisons between his protagonists and himself; but, these similarities once established, what he wanted the reader to marvel at was his ability to create topsy-turvy reconfigurations of his experiences when he set about converting them into fiction. The most obvious and striking example of the alchemical changes he performed—and that he desired us to know he’d performed—is the transposition of his own obsession with butterflies into Humbert’s obsession with nymphets; a close second would be the butterfly-like metaphorphosis of his work as a scholarly commentator on Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin into Kinbote’s gaudily hued annotations to Shade’s “Pale Fire.”

In a particularly unnerving passage in Lolita Humbert rhapsodizes on his desire to turn Lolita “inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys.” Pale Fire prompts us to speculate on whether Charles Kinbote is merely a fiction of his Wordsmith colleague, Professor V. Botkin, described in the book’s index as an “American scholar of Russian descent,” or indeed whether Botkin is a punning invention of Kinbote’s? The compulsion to turn life inside out, as Humbert longs to, or upside down as in the Kinbote/Botkin equation—perhaps this is as close as one can get to a delineation of the bars of Nabokov’s own particular cage. The Russian Revolution turned his world inside out and upside down; his novels are a means of doing something similar for all who read them.

The composition of both Lolita and Pale Fire also, it now seems clear, involved transforming material first developed in his own early verse plays: if Lolita rewrites aspects of the Wandering Jew theme explored in his 1923 verse drama Agasfer, Pale Fire’s account of revolution in a northern land has its source in The Tragedy of Mister Morn, composed by him in Prague in the winter of 1923–1924. It was first published in Russian in 1997, and is now available to English readers in a sparkling translation by Thomas Karshan—whose monograph Vladimir Nabokov and the Art of Play (2011) I also strongly recommend—and Anastasia Tolstoy, great-great-great-granddaughter of the novelist.

Nabokov claimed that by his early teens he had read all of Tolstoy in Russian, all of Flaubert in French, and all of Shakespeare in English. Although The Tragedy of Mister Morn is unashamedly Shakespearean, it never verges on pastiche. It seemed to me much more successful than most of the lyrics Nabokov wrote in his twenties and thirties, and that made his name as Sirin (Firebird) in Russian émigré circles in Berlin and Paris, and are now gathered, in his own son Dmitri’s translations, in Selected Poems. Mister Morn is set in a mythical kingdom not that different from Zembla. The title character is its secret king; he reigns brilliantly and decisively, but also anonymously, for he wears a mask when performing his royal functions and no one knows his real identity.

Two revolutionaries, Tremens and Klian, dedicate themselves to his overthrow, and eventually succeed in seizing power and unleashing horrific waves of mob violence. Julius Caesar is probably the Shakespeare play that most directly informs Mister Morn, but Tremens is no high-minded Brutus; Nabokov presents his revolutionary instincts as explicitly nihilistic: “Did you see?” he demands of Ganus, a former revolutionary who has just escaped from detention, and now doubts Tremens’s cause,

one windy night, by moonlight, the shadows

of ruins? That is the ultimate beauty—

and towards it I lead the world.

Nabokov had no time for the arguments in favor of Lenin, on whom Tremens seems partly modeled, put forward by Edmund Wilson and other American apologists for the Russian Revolution. Although vastly more eloquent and intelligent, Tremens is as compulsively dedicated to political violence as his late descendant, Jakob Gradus of Pale Fire. This, as Karshan points out in his introduction to The Tragedy of Mister Morn, allies him with a string of earlier literary nihilist revolutionaries such as Bazarov of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons and Pyotr Verkhovensky of Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed. Tremens’s feverish speeches communicate a repellent but lyrical bloodlust:

How splendidly,

how austerely, the old men died, and how

he screamed—O, sweeter than an ardent violin—

the little boy, their ward.

Mister Morn seems to me a valuable addition to the Nabokov canon. Its eponymous hero, as his name implies, stands for all that is opposed to the death instinct of the revolutionaries. “Had I not been King,” he muses, “I would have been a poet/with a lyre hot in this night, saturated/in blueness.” Something of Nabokov’s father’s grace, civility, and culture seems invested in the portrayal of Morn; for all the play’s Sturm und Drang and the complexities of its plot, it also, as in this comment by Morn, successfully reaches for the elegiac note that Shakespeare accords his heroes when they poignantly defy their losses as they near their end:

But we shall not—shall we?—talk of death,

—but with a bright conversation about

the kingdom, about power, and about

my happiness, you shall refresh my soul,

chase from the light the long, soft butterflies….

John Shade, four decades later, also alludes to his creator’s passion for the lepidopterous just before his untimely end, spotting “a dark Vanessa with a crimson band…its ink-blue wingtips flecked with white.” In their radically different ways, the antithetically named Morn and Shade, one coming at the dawn of Nabokov’s literary career, the other toward its evening, movingly embody the ideals that their creator pits against the pathology of violence—“curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy.”

Brian Boyd probably knows more about Nabokov than anyone on the planet, having written a comprehensive two-volume biography, split into The Russian Years and The American Years, both published in the early 1990s. Stalking Nabokov, a compendium of occasional pieces, reveals him pursuing his quarry across all manner of varying terrains: biographical, archival, scientific, psychological, and literary critical. We get essays developing obvious comparisons, such as “Tolstoy and Nabokov,” as well as pieces on obscure or unlikely topics, such as “Nabokov and Machado de Assis,” a nineteenth-century Brazilian writer of whose oeuvre, Boyd cheerfully admits, Nabokov had probably never read a word.

The essay that most caught my fancy was one that settled, once and for all I’d have thought, the vexed issue of the date of Humbert’s death. This is given in the “introduction” to the book by the fictitious John Ray Jr. as November 16, 1952. In the final chapter, however, Humbert tells us he had begun to write Lolita fifty-six days previously, first in a psychopathic ward, and then in the cell where he is awaiting trial. Fifty-six days from November 16 takes us to September 22, the very day Humbert received the letter from Mrs. Richard F. Schiller, formerly Lolita, beginning “DEAR DAD: How’s everything? I’m married….” It then takes Humbert three days to visit Lolita, extract the name of Quilty, track down his hated adversary to Pavor Manor on Grimm Road, and there dispatch his evil double—though only after reading him a hilarious parody of T.S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday.”

Accordingly, Humbert should either begin his “Confession of a White Widowed Male” fifty-three days before his death from coronary thrombosis, which occurs as soon as he completes his final rapturous paragraph (“I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art”), or the death date given by Ray should be amended to November 19, 1952.

A number of Nabokovians who spotted this discrepancy have taken it as a cue (if a Humbertian pun can be excused) to suggest that Humbert actually invented both his visit to Lolita and his messy but ultimately successful assassination of Q. This would make the last nine chapters of the book into an extended fantasy, an idea that has absolutely nothing to recommend it. Even Homer nods, as Boyd, as well as Horace and Pope, have pointed out, and our leading expert in the field of Nabokov studies must be right to suggest that the 6 in the book’s second sentence should be a 9. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, surely Vivian Darkbloom, Quilty’s shadowy collaborator and biographer, the letters of whose name can be reassembled to make that of Vladimir Nabokov, should be allowed to float free of the text a moment, to alight on that first page, and to make this small correction. Or should petition be made to the ghost—or executor—of John Ray Jr. to fix this tiny error in his inventor’s chronology? Consider it as a pawn a chess player has advanced one space, but kept under his finger for sixty years; he now wants to retract it.