Michael Hunt and Steven Levine write, “We came of age, amid the ferment of the 1960s, deeply concerned with the Vietnam War. Hunt lived in Vietnam early in that decade…Levine was an activist in the antiwar and civil rights movements.” Now retired, the two were colleagues at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, where they taught courses on Asian revolutions and US foreign policy. The broad outlines and many of the details in the Hunt and Levine study will be known to readers who remember or were active in the Sixties and early Seventies.

This is not a criticism; Hunt and Levine’s book benefits not only from the scholarship of the last four decades but from the debate over whether the US, having learned little and still bound by old convictions and blindnesses, is refighting foreign “wars of liberation” in the same destructive and self-destructive way. As Hunt and Levine state, “Both the violent rise and the long, painful decline of the American Pacific project offer a cautionary tale applicable to the US entanglement in the Middle East and Afghanistan.”

Arc of Empire’s propositions and conclusions are eloquently stated and for the most part, it seems to me, true. Of its four examples of the American attempts to impose empire, two, the Philippines and Vietnam, are convincing and will add to the knowledge of older readers and enlighten younger ones. The authors do not, however, persuade me that either Japan or South Korea fits their thesis about America’s destructive imperial tendencies.

Their main premise is clear: “Empire is fundamentally a centrally directed political enterprise in which a state employs coercion (violence or at least the threat of violence) to subjugate an alien population within a territorially delimited area governed by another state or organized political force.” The consequences of empire include collaboration with local elites, an army prepared to put down “restless natives,” military bases, imperial administrators, and ideological justifications aimed at both the home and the subject audiences.

In addition to the ideological justifications, which amount to “civilizing missions,” as the French used to say, American imperialism entered regions where previous colonial or dictatorial regimes had failed or were withdrawing. US military strategy then enforced control with overwhelming force, resulting “in the deaths of millions.” Finally there emerged a “strong, stable, and prosperous eastern Asia” as the US was either defeated or became exhausted and withdrew.

The authors claim they don’t “emphasize the motives behind empire.” But they do—and how curious it would be if they didn’t. For Americans, these motives include a denial of imperialism or colonialism, which they have always insisted were characteristic of Britain, France, Spain, or Holland. Nevertheless, the authors insist, the US was seeking “command of territory.” Then there was the claim that Americans are “champions of freedom.” More broadly this is underpinned by

a potent self-image as a unique people destined by geography, history, and moral character to guide politically immature and easily misled Asians to a better future…[combined with a] strong sense of exceptionalism and destiny….

In the Philippines, for example, “American rule was guided by a commitment,” according to a presidential commission, to “the well-being, the prosperity, and the happiness of the Philippine people and their elevation and advancement to a position among the most civilized peoples of the world.” Less loudly stated, but always in the background, was the domestic fear that failure would look weak, either to one’s internal enemies or to foreign allies or enemies.

One of the consequences of this self-image, Hunt and Levine argue, is that when the inevitable defeat or withdrawal came, rather than examining the reality of a determined adversary, Americans undertook an internal hunt for those responsible. Presidents starting with Harry Truman were accused of being weak-kneed and some of their advisers and many other government employees were falsely accused of being subversive, not only by such demagogues as Joe McCarthy but by the government’s own agencies.

However, before the US withdrew from several Asian countries, it inflicted, as the authors write,

high human and material costs on those who resisted. Destruction was visited upon one country after another, leaving masses of dead and maimed noncombatants as well as enemy soldiers…. Dominion came at a high price, but Americans paid little of it.

The invasion, occupation, and domination of the Philippines in the late nineteenth century is the book’s most potent example of America’s empire-building. It was preceded by the American occupation and subjugation of Hawaii, Midway, and Pearl Harbor, and the contest with Germany over Samoa. The onslaught on the Philippines was justified as a stroke against Spain, needed both to defend the US holdings in the Pacific and to secure an outpost in case other powers excluded the US from the carve-up of China. President McKinley spoke of the “childlike nature of the Filipinos” and of “destiny” and “duty.” And yet it was those same Filipinos who, like future targets of American subjugation, were to form a resistance movement. In this case the movement fractured, reformed, and ultimately lost. The Americans cultivated a native elite who were eager to link themselves to the conquerors, and were, Hunt and Levine contend, the predecessors of the families governing in Manila today.

Advertisement

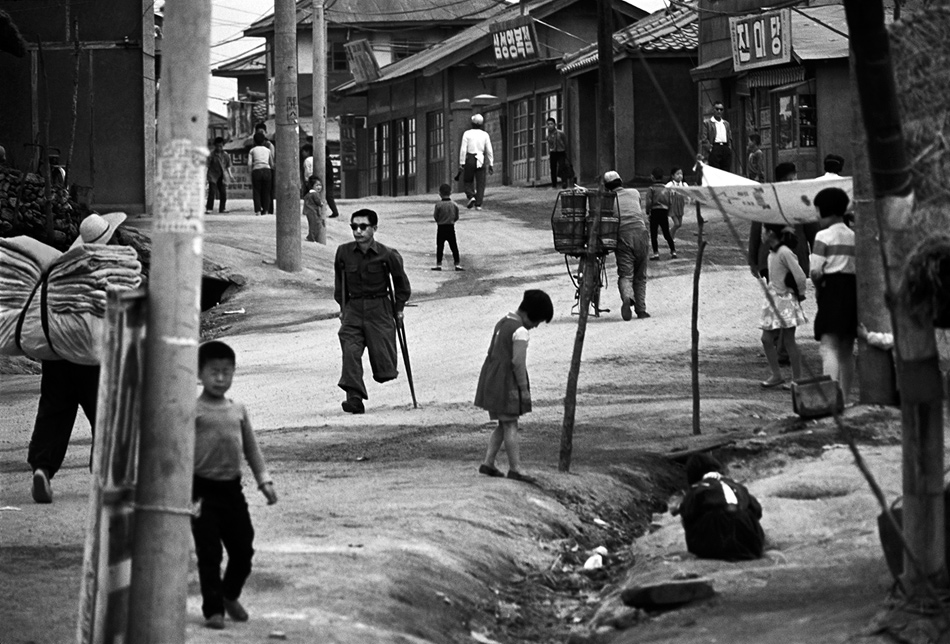

The military victory was made possible partly by army officers hardened in the wars against Native Americans and in the Civil War. It was also, the authors argue, partly made possible because, until not long before, the US had for two centuries enslaved black Africans. This history imbued many American nationalists with “a strong sense of racial superiority and entitlement justifying Anglo dominance over other, supposedly lesser peoples.” Dehumanization of the enemy in the Philippines was crucial to the ethos of counterinsurgency, with “nigger” and “gook” normal terms of abuse. (“Gook” resurfaced in Korea and I often heard the word used in Vietnam, sometimes for the forces of South Vietnam.)

In the Philippines civilians and prisoners were routinely mistreated, and what is now known as “waterboarding” was employed as the “water cure.” This was accompanied by a practice that later became routine in Vietnam: “collective punishment” was “commonplace, making entire villages suffer.” My Lai comes to mind. And as in Vietnam, “officers were not likely to report the excesses committed by their angry and racist troops.” It is notable, the authors write, that while the casualties among Filipinos were at least in the tens of thousands—and many estimates are higher—and the effects were more lasting than in any other American East Asian encroachments, the US impact on the Philippines is barely, if at all, taught in American schools or examined even by most critics of American policies and behavior abroad.

What the Americans could not have foreseen, however, was the effect farther east of their intrusion into the Philippines: growing fear in Japan and China that a new enemy was approaching. “As Japanese and Chinese observers clearly saw, the United States had become an imperial presence in eastern Asia…. The very fact of conquest dramatically signaled the emergence of a powerful and confident country on the shores of the western Pacific,” and this provoked and strengthened the region’s emerging nationalism.

Vietnam is the other inarguable example of what Hunt and Levine define as American imperialism in Asia. The terrible story of the Vietnam War is well known to readers of the The New York Review and has been minutely examined in many books, most recently Frederik Logevall’s Embers of War.* Here again, as in the Philippines,

Americans would take the place of one colonial power and set to work with collaborators in yet another exercise…sustain[ing] a client regime, [and] inflicting in the process enormous destruction and suffering upon the peoples of Indochina—Laotians and Cambodians as well as Vietnamese.

As has been often shown in this journal, there were those close to policymaking who understood the realities in Vietnam—above all the historic dislike of foreign aggressors reaching back over 1,500 years, the fear of American violence, and the popularity among many South Vietnamese, as even Eisenhower was to admit after he left the White House, of the Communist forces led by Ho Chi Minh. The authors say rightly:

The US commitment unfolded despite, not because of, the information available to US policymakers. The dreams of domination, doctrines of containment, and fears of policymakers trumped reality as the specialists so ably depicted it.

The authors do well, too, to quote President Johnson’s secret admission to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara about what would happen if the US left Vietnam: “I think it would just lose us face in the world. I shudder to think what [other countries] would say.”

There are some shortcomings in this analysis. Many North Vietnamese soldiers were not convinced that their welfare was important to “the fatherland,” as North Vietnamese novels—of which the authors are aware—make clear. It is not the case that the North Vietnamese soldiers “who became ‘martyrs’ could expect both symbolic and material recognition.” The authors make plain, moreover, that Communist morale was low, especially after the failure of the Tet offensive in 1968. There was a common saying among North Vietnamese soldiers: “Born in the north to die in the south.” Indeed, as several North Vietnamese novels show, it is remarkable that the Hanoi forces still fought with such determination and won.

In Vietnam, as in the Philippines,

Advertisement

those Americans suffered from one fatal flaw. They manifested colonial attitudes rooted in the previous century—a missionary confidence in the United States as a transformative force in the world and a conviction of cultural superiority over Asians seen as alternately barbaric and childlike….They were blind to the way nationalism had over half a century captured the imagination of educated Vietnamese.

Still, Hunt and Levine do not convince me that Japan and Korea also demonstrate American imperialism. Indeed, they begin their chapter on Japan with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Very quickly they move back to 1931 with Japan’s attack on China and even farther back to Japan’s late-nineteenth-century drive “to dominate the neighborhood as a matter of necessity and right.” The Japanese empire would soon include parts of China and Korea, Taiwan and Okinawa. Hunt and Levine emphasize Japan’s fear of US encroachment on its “neighborhood” after the occupation of the Philippines. Because they are scrupulous historians they observe that President Theodore Roosevelt, an “arch-imperialist,” was also convinced that “Japan was a civilized power deserving of a dominant regional role.” He wanted to “conciliate rather than confront Japan and to avoid a dangerous and costly naval race.”

Japan slid closer and closer to Berlin and Rome, and in 1936 it joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, followed four years later, on September 27, 1940, by its entering into a full-fledged Axis alliance. Tokyo “was now an integral part of a global threat to peace, the principles of democratic governance, and the European and global balance of power on which America’s own security ultimately rested.” The US was alarmed by Japan’s expansion and its militant policies, Hunt and Levine show. But despite an American fleet buildup, an oil embargo, aid to China, and the freezing of Japanese financial assets, the US administration wanted to avoid war with Japan.

In the light of these events and the authors’ own account, it is surprising to read that “in one fundamental sense the US war with Japan was a replay, to be sure on a much grander scale, of the war with the Philippines.” Just as McKinley had subdued the Philippines, Hunt and Levine argue, FDR “managed to beat the foe into complete submission within less than four years.” But this was World War II, and while the US used overwhelming violence, including two atomic bombs, to smash their (also racist) enemy, this was a life-and-death struggle with the forces of fascism. Stalin’s Soviet Union, itself a dictatorship responsible for millions of civilian deaths, bore the heaviest costs against Germany and only belatedly entered the war against Japan. Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs arguably was influenced by the US interest in limiting Soviet ambitions in Asia.

Inevitably, in Japan, as in Germany, came the victor’s occupation. Hunt and Levine argue that Japan’s leaders had created an opening that their American rival would exploit to the hilt:

Japan, rendered docile and subordinate by defeat, was the obvious place to start the building of a greater eastern Asia liberal prosperity sphere…the dissolution of the Japanese empire, the reduction of Japan to its four main islands, the abolition of the Japanese form of government prescribed in the Meiji Constitution of 1889, and its replacement by a modified form of American-style democracy.

Japanese militarism had been defeated together with German fascism and Germany was now also inside the American sphere. Violence had been used on an unprecedented scale to secure the victory but it was not used, as the authors would have it, essentially to “subjugate an alien population,” any more than the occupation of Germany subjugated the West German population. If the occupation of Japan, lasting from 1945 to 1952, was an example of the American empire, it was, above all, a brief one.

Nor does Korea fit the Hunt-Levine model. Here again, their own narrative makes this clear:

Several years of intense civil conflict on the Korean peninsula preceded the North Korean invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950…quickly drawing in the United States and its allies on the side of South Korea and China on the side of North Korea…. An inconclusive war doomed the divided country to a future of continued antagonism and tension.

Washington’s close relationship with the regime of Syngman Rhee formed part of Truman’s policy of containment of communism that reached around the globe: “Rhee and a shifting coalition of conservative nationalists would work with the Americans to build an anticommunist bastion south of the thirty-eighth parallel.” On the other side of that line was Kim Il Sung. Patriots and heads of police states, Rhee and Sung had emerged from the anti-Japanese struggle and, write Hunt and Levine, both

took profound pride in a rich, distinctive, ethnically homogeneous culture and in their country’s long history of independence…. They harbored a deep-seated distrust of outsiders with their deplorable record of demeaning Korean culture…. To emerge from Japanese domination only to suffer division as a result of great power [US-Soviet] diktat grated on the sensibilities of patriots north and south.

In short, neither Rhee nor Kim was a feeble pawn of a great power, and while the US, as it always had and does, showered destruction on both enemy soldiers and innocent civilans in Korea during World War II, this did not entail taking over a culture and people as had been the case in the Philippines and would be in Vietnam. On this point, one need read no more than these sentences by the authors:

The National Security Council…decided that the withdrawal of American troops [from Korea] should be completed by June [1949] so they could be redeployed to points more strategically important in case of war with the Soviet Union….Secretary of State Acheson…famously omitted Korea from his detailed survey of America’s Pacific defense perimeter.

This decision to withdraw does not at all follow from the authors’ first definition of empire I earlier quoted: “Coercion…to subjugate an alien population.”

As at Pearl Harbor, the surprise attack by the North Koreans in June 1950 caught Washington and especially General Douglas MacArthur by surprise; and the eventual stalemate, with China emerging as a major military force, “signaled the emergence of a new power equation in eastern Asia.” After this stalemate, or defeat, Hunt and Levine plausibly write:

Washington persisted in backing regimes in the Philippines, in South Korea, in South Vietnam, and on Taiwan that could not have survived on their own…. The overlapping array of authoritarian, right-wing clients and dependencies that Washington was pleased to call part of the Free World…[held] at bay the specter of revolutionary wars and subversion haunting the official imagination.

This leaves the impression, however, that the outcome might have been better, more realistic, less gripped by imaginary fear, had China taken over Taiwan, and North Korea the South. I do not see how anyone who has observed the history of Taiwan and South Korea in those years can believe they would have been better off if they had been ruled by Communist dictatorships, such as China’s, in which over 30 million people starved to death. Nor in 2013 can the Philippines, Taiwan, and South Korea be called authoritarian client states of the Americans. Indeed, without US involvement, Beijing would long ago have occupied Taiwan.

It is important to recall, too, as do Hunt and Levine, that it was the fanatically anti-Communist Richard Nixon who, “determined to set aside orthodox notions of the Cold War as a test between good and evil in which diplomacy constituted surrender,” opened negotiations with China and eventually was forced to accept retreat from Vietnam. Nixon always maintained, however, that the war could have been won if Congress had not cut off the funds to support it.

Despite my misgivings about the inclusion of Japan and Korea in their analysis of US imperialism in East Asia, I think Hunt and Levine are right to condemn the American imperial fantasy or “fairy tale” that took many forms, including these: “terrorized peasants, magically toppling dominos, a menacing Chinese dragon, and a United States about to become a pitiful helpless giant.” General David Petraeus and other US officers in Iraq and Afghanistan insisted repeatedly that they had learned lessons from Vietnam. To write their manuals containing these lessons, which nowadays are said to be included in the curriculum at West Point, Hunt and Levine describe how Petraeus and his “brain trust of younger officers…turned to distinctly colonial sources…French officers drawing lessons…from their own failed wars in Indochina and Algeria and from US marine and British ideas on pacification based on operations a century earlier.”

What American military planners wanted to know was how to operate in an alien terrain, how to win using powerful technology, and how to engage a local elite to “give local color to foreign intervention.” As the authors say, this remains the “culturally blind” approach that has long bedeviled Washington’s policymakers, and extends down to US soldiers handing candy to “native” children. As they mordantly observe in conclusion, if insanity involves making the same mistakes repeatedly, resolving “not to do empire” may be a step toward sanity.

In Vietnam I occasionally met US lieutenants and captains who read Mao and Ho on guerrilla warfare, but I saw no effects of this reading on the ground. Somewhere in Afghanistan, however, there may be more imaginative, “sane” American officers, probably still of junior rank, who will read Michael Hunt’s and Steven Levine’s thoughtful and necessary Arc of Empire, including its comprehensive citations. They may realize that they are engaging in a mistaken—and destructive—project that has lasted well over a century.

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Cool, Yet Warm

Facing the Real Gun Problem

-

*

See my review in these pages, “A Debacle That Could Have Been Avoided,” October 25, 2012. ↩