Can genes be patented? This spring, the Supreme Court will hear a case that may well decide the question, and the consequences for American biomedicine could be huge.1 Over three years ago, in May 2009, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Public Patent Foundation (PPF) filed a lawsuit in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York seeking to overturn the patents on DNA isolated from two human genes.2 Called BRCA1 and BRCA2, the genes significantly increase a woman’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The main defendant was the Myriad Genetics Corporation, a biotechnology firm in Utah that controls the patents—and is legally entitled for the life of the patent (now twenty years) to exclude all others from using these genes in breast cancer research, diagnostics, and treatment. Other defendants were the University of Utah Research Foundation, which had come to own the patents, and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO), which had granted them.

The plaintiffs were not the usual parties in patent suits: competitors concerned with their balance sheets. They included medical geneticists, pathologists, and advocates for women’s health, as well as biomedical researchers, genetic counselors, and several women with breast cancer or at risk for it. They were distressed that Myriad’s patents allowed it to exercise such monopolistic control over a biological substance as essential to research, medicine, and patients as DNA implicated in cancer. They contended that BRCA DNA—and by implication all human DNA—should not be eligible for patents as a matter of law and that Myriad’s enforcement of its patents interfered with the progress of science and the delivery of medical services.

The plaintiffs had the support, expressed in friend-of-the-court briefs, of many parties representing the medical profession, biomedical researchers, and patients, all opponents of allowing anyone monopoly rights on human DNA. The Myriad Genetics Corporation, however, had many allies from the biotechnology industry, patent lawyers, and various genomic companies—all of whom said the grant of such rights was needed for their business. In American law, opponents of a public policy cannot ordinarily pursue their objections in the federal courts, including in patent suits, unless the policy causes an injury that gives them standing to sue.3 The plaintiffs contended that they had suffered harms, offering in evidence how Myriad enforced its BRCA patents—in the clinic and the laboratory—to stop others from using the genes to do research on cancer. On November 2, 2009, over the objections of Myriad and the PTO, Judge Robert W. Sweet, the presiding judge, granted all the plaintiffs standing to sue Myriad, holding that, given the gravity of the issue for health and science, they had every right to call Myriad, the PTO, and gene patents to account.

In a sense, the case had originated in 1990, when a geneticist at Berkeley announced that her laboratory had tracked the location of BRCA1 to somewhere on chromosome number 17.4 A transatlantic race then ensued to find the exact position of the gene, and a major competitor was Mark Skolnick, a respected and enterprising geneticist at the University of Utah and a cofounder of Myriad Genetics. Supported by venture capital and both funds and collaborators from the National Institutes of Health, Skolnick and his colleagues won the race in 1994, finding BRCA1 and isolating it from the rest of the DNA and the tangle of protein that form chromosome 17. In 1995, Myriad’s scientists also identified and isolated BRCA2, which resides on chromosome number 13.5

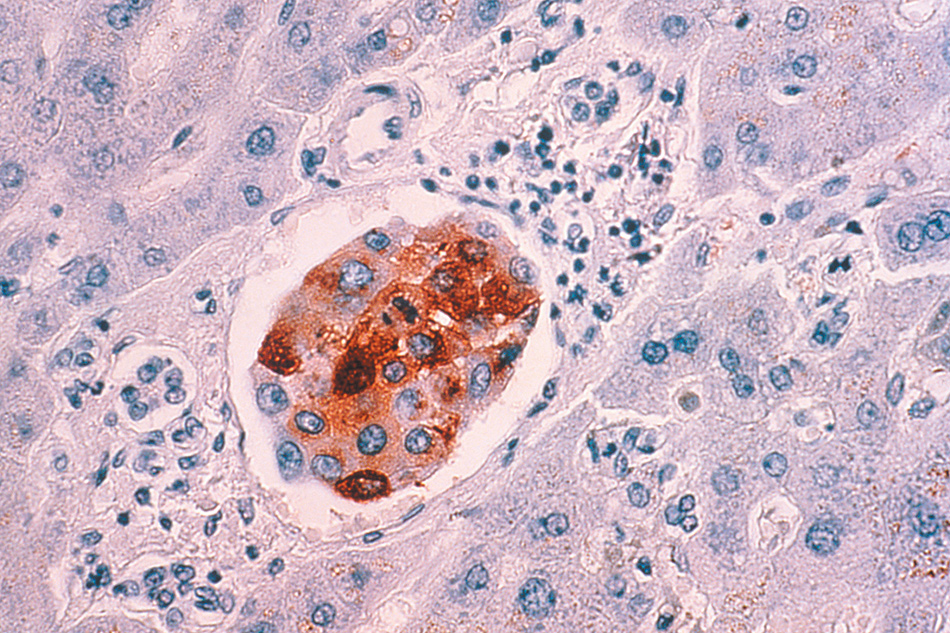

The DNA in the two BRCA genes, like that in other human genes, is a double helical molecule, each side of which is joined, like the rungs of a ladder, by two complementary chemicals called base pairs—adenine, which always links to thymine, and cytosine, which always links to guanine. The order in which the base pairs occur along the helix—that is, their sequence—comprises the genetic code. Myriad sequenced the two genes and found that each is a version of a normal gene that has been corrupted by changes such as mutations and rearrangements that alter the sequence in the DNA.

In 1994, Myriad, omitting its collaborators from the NIH, applied for patents on both the isolated DNA that makes up the BRCA1 gene and also on a set of diagnostic tests to detect its presence. In 1995, it did the same for the isolated DNA of BRCA2. In 1997 and 1998, the PTO awarded a total of seven patents on the two isolated genes, various DNA fragments within them, and the diagnostic tests to find them.

The US patent system rests on ideas of political and moral economy current in the era of the American Revolution.6 Along with many colonists, Thomas Jefferson long opposed the monopolies inherent in copyrights and patents, but James Madison persuaded him of their value as incentives to authors and inventors, so long as they were only temporary. Thus Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the US Constitution, now often called the “Progress Clause,” authorizes Congress “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” In the patent law of 1793, Congress defined eligibility partly in language that Jefferson provided and that remains at the heart of the statutory code (USC Title 35, Section 101) for the subject. According to the statute, patents could be obtained for “any new and useful art”—the word was replaced in 1952 by “process”—“machine, manufacture, or composition of matter [Jefferson’s phrase], or any new and useful improvement…[thereof].”

Advertisement

Jefferson’s language emphasized the requirement of newness, or novelty, and bespoke the necessity of an inventive step. It also implied that products made by nature, which were held to belong to everyone, were not to be removed from common possession. Thus products of nature such as the naturally occurring elements in the periodic table or the creatures of the earth, being neither new in the world nor made by man, were taken to be ineligible for patents. So, tacitly, were laws of nature, natural manifestations, abstract ideas, and thought.

During the following two centuries, these exclusions from patent eligibility came to be explicitly articulated in a body of federal court decisions holding, for example, that natural elements taken from the earth, even if they had to be chemically isolated from other substances, did not constitute patentable subject matter under Section 101, if only because they were not new.

Nevertheless, in the 1980s the PTO began issuing patents on DNA—not DNA in the body, which was indisputably a product of nature—but on three different versions of DNA isolated from the body. Scientists call one of them “complementary DNA,” or cDNA. In a gene, only some of the base pairs in the sequence along the double helix are “expressed”—that is, they prompt the production of some of the amino acids that the cells then assemble into the body’s proteins. The rest of a gene’s base pairs—which make a large majority of them—are not expressed. cDNA is constructed of only the expressed base pairs organized in the same order as they occur in the native gene, omitting the rest. The other two patented versions of DNA comprised isolated fragments or the whole of the raw DNA in a gene. Myriad’s patents extended to all three types of DNA extracted from the two BRCA genes.

The PTO did not provide a full legal justification for granting such patents until January 2001, when it issued “Utility Examination Guidelines” to clarify the criteria that patent claims on DNA would have to satisfy.7 There it justified patents on isolated DNA by drawing primarily on two long-standing judicial doctrines. The first was that products of nature can become eligible for patents if—to quote from the Supreme Court’s ruling in 1980 in Diamond v. Chakrabarty, a landmark case that allowed patents on a genetically modified bacterium—they had “markedly different characteristics from any found in nature.”8 The second originated with Judge Learned Hand in Parke-Davis v. H.K. Mulford, a case decided in 1911 that concerned Parke-Davis’s patent on adrenalin, which a chemist had isolated from the body, purified, and produced in concentrated form. In what lawyers term “dicta”—assertions by judges that are neither essential to decisions nor legally binding but that are potentially influential—Hand declared that, having been extracted, purified, and thus made useful, the adrenalin “became for every practical purpose a new thing commercially and therapeutically.” He added, “That was a good ground for a patent.”9

To summarize the reasoning of the PTO: cDNA, which is made by scientists outside the body, differs markedly from the DNA inside it. So does the raw DNA extracted from the body, whether the whole of a gene or a fragment of it: when it is chemically disentangled from its chromosomal housing it becomes a new composition of matter. The PTO holds all three versions eligible for patents in accord with Chakrabarty, and patentable in keeping with Hand’s dicta because, in isolation, they are new and useful commercially, diagnostically, and possibly therapeutically.

The plaintiffs contended before Judge Sweet that the patents should never have been granted on either the DNA or the tests because, according to the patent law (Section 101) and judicial rulings, neither was “patent-eligible.” Myriad’s diagnostic methods boiled down to comparing the base-pair sequence in the DNA taken from a patient with the sequence in a version of the gene that will dispose the person to cancer. The plaintiffs pointed out that the comparison did not require any particular process but only the act of looking at one sequence and seeing whether or not it matched the other. The “claim” (the term refers to the elements in what a patent covers) was therefore to abstract ideas and thought and as such was excluded from patentability.

Advertisement

Whether BRCA DNA could be patented turned primarily on whether any of its three extracted forms in fact were a new composition of matter. The plaintiffs contended that none of them was. The extracted DNA might be useful enough in isolation to meet the criterion of patentability laid down by Learned Hand. But the plaintiffs argued that Hand’s dicta was of dubious merit at the time and that it had in any event been overridden by a series of Supreme Court decisions culminating in the criterion advanced in the Chakrabarty case that, to be patentable, the material in question had to be “markedly different.”

In the plaintiffs’ argument, both the raw DNA and the cDNA forms embodied the same sequences of cancer- disposing base pairs—the same defining genetic information—as did the native genes. The extracted raw DNA differed in material composition only trivially from the native version. It was no more transformed from the natural DNA than was gold upon removal from a stream bed or the yolk after separation from the rest of the egg.

Christopher Hansen, one of the ACLU’s co-counsels, has said that the plaintiff’s lawyers approached the suit as though it were a civil rights case, reaching beyond the technicalities of patent law to emphasize that the patents, as well as the 2001 “Guidelines” on which they rested, enabled Myriad to infringe the rights of biomedical scientists, physicians, and patients.

Myriad’s patents are sweeping, covering both the corrupted and normal versions of each isolated form of BRCA DNA and all mutations and rearrangements within them, including—by implication for the BRCA1 gene and explicitly for the BRCA2 gene—those as yet unknown. They also encompass every conceivable use of the three types of DNA, including diagnostics, therapies, drug development, and the identification of other cancers involving either of the genes.

The patents gave Myriad a virtual lock on research and diagnostics on the workings of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes because, for the most part, such research and diagnostics required analysis and manipulation of the DNA in isolated form. Myriad, exercising the power of exclusivity inherent in its patents, reserved to itself the performance of all diagnostic analyses of a patient’s DNA that might be disclosed to her. According to the complaints of the plaintiffs, Myriad’s policy enabled it to charge prices for the tests that put them beyond the reach of some women. It also prevented patients from obtaining a second diagnostic opinion from an independent laboratory. And it forced clinical researchers who scrutinized a woman’s DNA to violate the ethical norms of medical practice because they were prohibited from telling her what they found. Myriad’s policy hampered such research because women at risk were disinclined to participate if the outcomes had to be kept from them.

The company blocked several biomedical scientists from conducting clinical research on the BRCA DNA, except under severe restrictions. It could, if it wished, prevent scientists from exploring the meaning of mutations of unknown significance that the tests might reveal. Myriad also kept for itself the right to incorporate the discovery of the new alterations in the BRCA genes, even those made by others, into the diagnostic tests. It thus retarded the development of the most comprehensive tests possible for women at risk. Except as the company allowed, no other laboratory could assess the reliability of its tests or improve upon their speed or cost.

Myriad’s control over BRCA DNA differed little from that established by a patent on any other molecule, but the plaintiffs emphasized that DNA was not just another chemical. Even in isolated form, it embodies the gene’s natural repository of genetic information and its ability to express laws of nature. Moreover, genes are not only special natural products; each is also unique in its composition and function. No one can invent another BRCA1 or BRCA2 any more than someone can devise a different hydrogen or oxygen. Finding another gene that predisposes a woman to breast or ovarian cancer will not help identify whether she is at risk for either BRCA1- or BRCA2-induced illnesses.

Breaking new ground in a patent case, the plaintiffs contended that Myriad’s patents—and by clear implication the policy that enabled them, notably the 2001 “Guidelines”—violated the US Constitution, particularly the Progress Clause and the First Amendment. By empowering Myriad to control all research and uses of a unique part of nature, the patents impeded the progress of science and the useful arts. By restricting access to and use of the genetic information that the DNA embodied, they gave Myriad control over all “thought, knowledge, and ideas” concerning the genes, a monopoly that the First Amendment, in accord with judicial holdings, prohibited the PTO from granting.

Opponents of human gene patenting had raised similar substantive warnings when the PTO was devising its 2001 “Guidelines.” The PTO had then summarily dismissed these objections, citing Section 101, Learned Hand’s dicta, and Diamond v. Chakrabarty. Myriad’s lawyers now flatly rejected the constitutional challenges to its patents, deriding them as “frivolous atmospherics” and calling “false” the charge that its patents “directly limit thought and knowledge.” They declared that the company “freely” allowed academic research on both genes and that more than eight thousand papers about the genes had been published around the world.

They neglected to say that the scientists involved had to avoid violating Myriad’s restrictions on the uses of the DNA covered by its BRCA patents. Both Myriad and the PTO sidestepped the impossibility of inventing alternatives to the BRCA genes, resorting to the irrelevance that patents like Myriad’s would stimulate competitors to identify predispositions to cancer through “research on other genes.” Myriad asserted that the company publicly disseminated the results of its own investigations of the two genes. In fact, it had ceased contributing its data to an international breast cancer consortium in 2008.10 Myriad said that there was no need for women to seek a second, independent diagnostic opinion because its tests were recognized, according to the company’s then president, Gregory C. Critchfield, as “the gold standard” in the field.

In March 2010, Judge Sweet struck down Myriad’s patents on the isolated BRCA DNA and the diagnostic methods that Myriad used to determine whether a patient possesses the genes herself. Accepting a number of the plaintiffs’ main arguments, he repudiated Hand’s dicta as questionable at the time and “certainly no longer good law in light of subsequent Supreme Court cases.” He held, moreover, that the isolation of the BRCA DNA, in whichever form, did not alter its “essential characteristic”—the sequence of base pairs that made it a carrier of genetic information. Myriad’s BRCA DNA was thus not eligible for a patent as a new composition of matter.11

Myriad appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, in Washington, which hears all appeals in patent cases. The appeals court found reasons to deny standing to all but one of the plaintiffs—he was Harry Ostrer, a biomedical scientist then at NYU—but one sufficed for the suit to remain active. On July 29, 2011, in a split decision, a three-judge panel of the court partially reversed Judge Sweet by upholding Myriad’s claim that the BRCA DNA is eligible to be patented. In December, the ACLU and the PPF petitioned the Supreme Court for a review of the case.

On March 26, 2012, the Supreme Court vacated the finding of the Court of Appeals, instructing it to reconsider that ruling in light of a decision the Court had announced a week before in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories. In that case, the justices unanimously struck down a patent that covered the relationship between the size of a drug dose and the level of certain metabolites in the blood. Speaking for the Court, Justice Stephen Breyer held that the relationship was unpatentable because it constituted a law of nature. Breyer noted the Court’s repeated emphasis that a patent required an “inventive concept” and “that patent law not inhibit future discovery” or “impede innovation more than it would tend to promote it” by granting monopolies over use of laws of nature, natural phenomena, manifestations of nature, and abstract ideas.12

When the Court of Appeals reconsidered the case, a friend-of-the-court brief on the relevance of Mayo on behalf of neither party was filed by the Department of Justice. In an extraordinary move the year before, the department had filed a friend-of-the-court brief with the Court of Appeals in opposition to the Obama administration’s PTO. Aware of the broad stakes in the case, the Justice Department lawyers had pointed out then that DNA extracted from the body was no more patent-eligible than any of the natural elements in the periodic table—lithium, for example—that had to be separated chemically from the compounds in which they occur in the earth. Now, along with the plaintiffs and several other friends of the court, it found “indirect guidance” in the Mayo ruling for the disposition of the Myriad case, contending that a patent

that effectively prevents the public from studying and making use of a product of nature is just as objectionable, and for the same underlying reason, as [one on] a method…that effectively prevents the public from studying and exploiting a law of nature.

On August 16, 2012, a Court of Appeals panel, composed of the same three judges who had dealt with the case the year before, unanimously affirmed Judge Sweet’s ruling against the patentability of Myriad’s diagnostic methods, finding them tantamount to a law of nature, but otherwise overturned his decision once again. The panel held unanimously that cDNA itself is patent-eligible because it is markedly different from the DNA in the body, and, most important, it ruled 2–1 that the other forms of isolated BRCA DNA, whether the fragments or the whole of the gene, are also eligible to be patented.

The principal in the court majority was Judge Alan Lourie, who had been an organic chemist before turning to the law. He insisted that in patent law, unlike in biology, BRCA DNA was not information but was solely a chemical compound. Having been chemically modified at its ends upon extraction from its neighboring DNA, it differed sufficiently from the native version to be patent-eligible. He dismissed the Mayo ruling as irrelevant to the case, embracing arguments made by Myriad’s lawyers that the justices’ ruling in that case concerned a biomedical process while the Myriad case concerned DNA, a composition of matter.

Judge Kimberly A. Moore, an electrical engineer by original training, concurred with Lourie’s opinion, but reached her conclusion by a different route. Mayo meant to her, in contrast to Myriad’s lawyers, that products of nature were no more patentable than laws of nature, and in her view, contrary to Lourie’s, the extraction of the BRCA DNA from its natural habitat did not make it adequately different from the native version to warrant a patent. But she held that the fragments of isolated BRCA DNA were made patent-eligible by the combination of their difference from BRCA DNA, however small, and their usefulness as diagnostic probes.

The complete DNA of the BRCA genes presented Moore with “a more difficult issue” because such isolated DNA did not differ markedly from its native counterpart and was not yet useful. Moore held that if the case had come before her prior to the development of the biotechnology industry, she might have decided differently on the merits. But she was mindful of the huge accumulated investment that rested on patents that the PTO had been issuing on isolated DNA for thirty years. Moore held the isolated DNA of the entire BRCA gene patent-eligible on grounds that not to do so would violate the industry’s “settled expectations and extensive property rights.”

The reasoning of Judges Lourie and Moore provoked an acid dissent from Judge William Bryson, who had come to the bench via a career in the Department of Justice rather than the patent bar. To his mind, the isolated BRCA DNA was fundamentally the same in structure and function as the DNA in the body. It was no more a human invention because it had been isolated from the chromosome than was a kidney taken from the body, a limb removed from the tree, or a mineral or plant extracted from the earth.

The Court of Appeals’s several opinions made explicit that the case pitted the property rights of innovators and investors in gene-based biotechnology against the rights of free access to and use of human DNA by researchers, physicians, and patients. In effect, the absolute control inherent in DNA patents protects—and thus privileges—this sector of the biomedical complex against all others who have reasons to make use of human DNA. The instrument of the privilege is the current strict interpretation of patent law that is guided beyond legal logic by concerns for incentives to innovation and investment.

The PTO had adhered to this approach when it dismissed the arguments of the dissenters from human gene patents in the course of devising the 2001 “Guidelines.” Judge Lourie followed suit, noting explicitly in his opinion that the case was not about, for example, a patient’s right to a second diagnostic opinion or whether it was “desirable for one company to hold a patent or license covering a test that may save people’s lives.”

Judge Moore did acknowledge that Myriad’s patents “raise substantial moral and ethical issues” about the allowance of property rights in “human DNA—the very thing that makes us humans, and not chimpanzees,” and she allowed that BRCA DNA “might well deserve to be excluded from the patent system.” But she considered such a “dramatic” destruction of property rights properly the province of Congress, not the courts.

Against this strict view of patent law stands an expansive version of it, consistent with the Progress Clause, that recognizes the adverse consequences in the clinic and the laboratory of monopoly control over human DNA, a scientifically and medically essential substance for which there is no substitute. The plaintiffs advanced the expansive version of the law, and so did Judge Bryson. He found good reasons in the Mayo ruling to reject Myriad’s patents, noting that they lacked an inventive concept and that they would interfere with future research and innovation.

On September 25, 2012, the plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to review the Court of Appeals’s August decision and on November 30 the Court accepted the case, confining its review solely to the fundamental question of whether genes are patentable.13 Its decision will determine whether the narrow or expansive interpretation of the law will apply to human DNA. In effect, to borrow from Madison’s assurance that patent monopolies posed no danger in the American democracy, it will declare whether the rights of the many—scientists, physicians, and patients—will be given standing in what has long been the province of the biotechnological few.

-

1

Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics Inc. ↩

-

2

The decision of the District Court and the opinions of the Appeals Court are freely available at dockets.justia.com and www.aclu.org, respectively. All case documents, including briefs and decisions, are available through WestlawNext at store.westlaw.com/westlawnext. ↩

-

3

See Ronald Dworkin, “The Court’s Embarrassingly Bad Decisions,” The New York Review, May 26, 2011. ↩

-

4

The normal human genome contains the sex chromosomes X and Y plus twenty-two pairs of other chromosomes that are numbered in order of their relative size. ↩

-

5

See Kevin Davies and Michael White, Breakthrough: The Race to Find the Breast Cancer Gene (Wiley, 1996); Shobita Parthasarathy, Building Genetic Medicine: Breast Cancer, Technology, and the Comparative Politics of Health Care (MIT Press, 2007). ↩

-

6

See Lewis Hyde, Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010). ↩

-

7

US Patent and Trademark Offfice, “Utility Examination Guidelines,” Federal Register, Vol. 66, No. 4 (January 5, 2001), pp. 1092–1099. ↩

-

8

Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 US 303, 100 S. Ct. 2204 (1980), available at supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/447/303/case.html. ↩

-

9

Parke-Davis & Co. v. H.K. Mulford Co., 189 F., 95 (April 28, 1911). See Jon M. Harkness, “Dicta on Adrenalin(e): Myriad Problems with Learned Hand’s Product-of-Nature,” Journal of the Patent and Trademark Office Society, Vol. 93, No. 4 (2011), pp. 363–399. ↩

-

10

By halting its contributions to public data bases, Myriad aimed to protect as trade secrets its accumulating knowledge about additional alterations in the two genes and thus to maintain a strong hold on fully comprehensive testing for corrupted versions of them even after its patents expire. Andrew Pollack, “Despite Gene Patent Victory, Myriad Genetics Faces Challenges,” The New York Times, August 24, 2011. ↩

-

11

Judge Sweet, having decided the case on statutory grounds, followed standard judicial practice by declining to address the constitutional issues, which mooted the plaintiffs’ challenge against the PTO. ↩

-

12

U.S. S.Ct., Court Orders, Case 11-725, available at www.supremecourt.gov; Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, 566 U.S., “Syllabus,” p. 3; Decision, p. 2 (2012); Adam Liptak, “Justices Back Mayo Clinic Argument on Patent,” The New York Times, March 20, 2012. ↩

-

13

Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court to Look at a Gene Issue,” The New York Times, November 30, 2012. ↩