“Il faut être absolument moderne,” wrote Rimbaud, but for Baudelaire, his immediate predecessor in the dissenting chair of French poetry, the matter was considerably more fraught. Roberto Calasso remarks that he “abhorred the new that the world was throwing up in abundance all around him, yet the new was both the host and demon indispensable to what he wrote.” After all, “the modern was everything Baudelaire had come across.”

Jules Laforgue, another of his heirs, drew up an impressive list of his firsts:

He was the first to tell his tale in the moderate tones of the confessional and without assuming an inspired air…. The first to speak of Paris like an everyday damned soul of the capital…. The first who was not triumphant but accused himself…. He was the first to break with the public….

In his notes Laforgue listed Baudelaire’s attributes: “cat, Hindu, Yankee, Episcopal alchemist”—“Yankee” to mean “excessive.” And yet, Calasso points out, “All his poetry seems translated from Latin. Or sometimes a variation on a draft by Racine.”

The “folly” that gives Calasso’s book its title is a double-edged image derived from the double-edged and rather reptilian Sainte-Beuve:

M. Baudelaire has found a way to construct, at the extremities of a strip of land held to be uninhabitable and beyond the confines of known Romanticism, a bizarre pavilion, a folly, highly decorated, highly tormented, but graceful and mysterious….

Its denizens read Poe, “recite exquisite sonnets,” ingest hashish and opium, and so on. “The author is content to have done something impossible, in a place where it was thought that no one could go.” Sainte-Beuve was a master at undermining praise in the very act of dispensing it. His lyrical description of the folly—“its marquetry inlays, of a planned and composite originality”—was actually intended to blackball Baudelaire from being nominated to the Académie Française; needless to say, it worked.

Calasso finds Sainte-Beuve’s conceit oddly prefigured in a dream Baudelaire recounted to his friend and eventual biographer Charles Asselineau. In the dream the poet finds himself going to offer a copy of his book to “the madam of a great house of prostitution” and, by the way, get laid. After experiencing a number of typical dream-humiliations (his penis is hanging out of his pants; he is barefoot, or has on only one shoe), he notices “immense galleries” in which, among “obscene,” architectural, and Egyptian figures, he sees a series of small frames containing pictures of

colorful birds with the most brilliant plumage, birds with lively eyes. At times, there are only halves of birds. Sometimes they portray images of bizarre, monstrous, almost amorphous beings, like so many aerolites. In the corner of each drawing there is a note. The girl such and such, aged…brought forth this fetus in the year such and such….

Baudelaire speculates that this combination of a brothel and “a kind of museum of medicine” could only have been financed by Le Siècle, a liberal newspaper with a

mania for progress, science, and the spread of enlightenment. Then I reflect that modern stupidity and arrogance have their mysterious usefulness, and that often, by virtue of a spiritual mechanics, what was done for ill turns into good.

Finally he meets an inmate, “a monster born in the house,” who stands on a pedestal all day as a museum exhibit, and has “something blackish wound several times around his body and his limbs, like a large snake,” which emerges from his head and makes it difficult for him to move around. “He gives me all this information without bitterness. I dare not touch him—but I’m interested in him.”

Calasso proceeds to explicate the dream. The new book of Baudelaire’s then, in 1856, was his translation of Poe’s Extraordinary Tales, than which nothing could be less obscene; the first recipient of a presentation copy could hardly be the madam of a great brothel. Therefore “we may plausibly suppose that [the dream] already saw the book as Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, due to be published a year later and immediately confiscated and condemned for obscenity.” That the brothel is also a museum evokes Baudelaire’s rhapsody in his Salon of 1846, wishing for

a museum of love, where everything would have its place, from the tenderness of Saint Theresa to the serious depravations of the centuries that were bored with everything. No doubt an immense gap separates the Embarkation for Cythera [by Watteau] from the wretched colored prints one finds in the rooms occupied by the whores…but in a matter of such importance nothing must be overlooked.

Calasso notes that “the brothel-museum and the ‘museum of love’ were almost identical, yet basically divergent and incompatible.”

The clue to their difference is the underwriting of the brothel-museum by Le Siècle, a newspaper that was once the leading monarchist tribune (and the venue for a number of Balzac’s serialized novels). Now, in 1856, it is republican and progressive and, as such, the temple of the bêtise, which is to say of commonplace bourgeois idiocy elevated to the level of resounding truth—Le Siècle was the “ideal paper” of Bouvard and Pécuchet. The word bêtise, though, is nuanced. “Great poetry is essentially bête, it believes, and this is what makes its glory and strength,” wrote Baudelaire in a review in 1846; while Flaubert, in a letter of 1852, wrote: “Masterpieces are bêtes. They have a tranquil air like the very productions of nature, such as big animals and mountains.” As a noun, bête means “beast”; it is more than a simple slur, instead suggesting something primal, nonreductively animalistic. Hence, “the great brothel that is also a museum of medicine presupposes that we have reached a very high level, perhaps a dizzying one, of bêtise.” But if “what was done for ill turns into good,” which is which? Is the brothel justified because it hosts a museum, or is the museum justified because it is housed in a brothel? Which of the two is less bête? Baudelaire is untroubled by the problem: “I admire in myself the rightness of my philosophical spirit.”

Advertisement

Calasso makes a persuasive case for the dream’s monster being Baudelaire himself—grotesque, tormented, constantly on public display, subject to erotic humiliation. “He had always felt keenly extraneous to himself, willing to look at himself as an other.” But Calasso does not wrap up anything too neatly. The brothel-museum may be Sainte-Beuve’s folly, but it is also “a huge, boundless mnemotechnical edifice,” and in some ways it is Paris, the Paris of the passages; it is a world and a counterworld. Here as elsewhere, Calasso is pointing his flashlight down dusty corridors, making suggestive connections, free-associating in such densely upholstered fashion that “free association” seems far too undisciplined as a label for what he does. The brothel-museum stands literally as well as figuratively at the center of his book, so that the book might be said to radiate from it (the folly, on the other hand, does not appear until nearly the end), but that does not mean that the structure necessarily constitutes an argument, let alone one shaped like a secret society.

Calasso’s subject is Baudelaire’s sensibility. He makes the point that Baudelaire has undergone every “kind of psychological dissection, all of them clumsy and inopportune.” Not only did he go “beyond literature,” he came to incarnate “a psychic climate…a certain way of feeling alive.” Baudelaire’s sensibility therefore continued on, as a sort of autonomous drift, after his death. At its root is his famous pursuit of correspondences—“his Muse, whose name was Analogy.” The concept derived from the Renaissance Neoplatonists—Bruno, Paracelsus, Kircher—and had been revived in Germany, by Goethe for one, but Baudelaire absorbed it primarily from his century’s great eccentric creators of systems, Charles Fourier and Emanuel Swedenborg.

Appropriating Swedenborg’s idea of “correspondences,” Baudelaire fashioned a sort of notional map, as loosely defined as it was telling, in which internal emotional states and manifestations in the external world mirrored one another through synesthesia—aromas, tastes, and colors mingling and exchanging properties, all of them subject to mediation by words. Baudelaire, however, was not one to traffic in systems of any sort, “so there was nothing else to do but proceed through a multiplicity of levels, signs, images, without any guarantee either of the starting point, always arbitrary, or the end point, which, in the absence of a canon, one was never sure had been reached.” Baudelaire’s metaphysics are intuitive, unconscious, forever suggestive of method, always elusive.

Whatever they were, they propelled him on an obsessive quest for images, and that is in large part what Calasso is concerned with. He is building up a panorama of “modernity,” which Baudelaire himself defined in The Painter of Modern Life as “the fleeting, the transitory, the contingent; it is one half of art, of which the other half is the eternal and unchanging.” He is depicting the landscape Baudelaire walked in even as he altered it, and accordingly, he focuses on painters, among others Ingres, Delacroix, Degas, and Manet, not forgetting Constantin Guys, Baudelaire’s “painter of modern life.” Degas and Manet are the surprise insertions: they entered the scene after his death and never met him, but in many ways they were formed by him. Calasso has more to say about some of these than others—Delacroix rates a bare ten pages, but then Baudelaire’s sympathy with him is well known. He took the side of Delacroix in the great polarity that dominated early-nineteenth-century painting, where Ingres stood for line and Delacroix for color, Ingres for drawing and Delacroix for direct painting, Ingres for classical order and Delacroix for wild untamed modern sensibility.

Advertisement

Calasso is more interested in pursuing Ingres: “one of those extremely rare people who are nothing but geniuses.” Ingres was crass, unreflective, inarticulate, “impervious to culture.” He was a boorish bourgeois down to his appearance, which one of his own supporters wrote “had everything that might clash with the elegance of his thoughts and the beauty of his female figures.” One of his enemies, Théophile Silvestre, wrote:

It’s difficult to remain serious in the presence of this coarse majesty whose brow is girt with a triple crown: the nightcap, the laurel wreath and the halo…. M. Ingres comes to establish the cult of form through the abolition of thought itself.

But then, he couldn’t help himself. His drawing was instinctive, compulsive, somewhere between a religion and a tic. The only time he spoke to Degas he urged him to “make lines, lots of lines.” He was, as Peter Schjeldahl wrote of Picasso, “a line-drawing critter.”

Ingres’s contemporary reputation as a paragon of classical order disguised his strangeness, his quite unconscious radicalism. His “world was made of metal, gem stones, fabrics, enamels.” His sense of color, for all that the Académie des Beaux-Arts, appraising his Jupiter and Thetis, called it “feeble or unvarying,” was, “if anything,…irritating because of its ostentatious excess.” Baudelaire may have been rallying to Delacroix when he wrote that “M. Ingres adores color, like a haberdasher,” but he could see the merits of Jupiter quite clearly: “Open your eyes, O foolish nation, and say if ever you saw more dazzling and more sumptuous painting, as well as a greater exploration of tones?” And unlike his peers, who took photography as a base mechanical process and a threat not only to their profession but to their view of the world, Ingres “incorporated photography into his painting long before it was invented”—as early as 1806 his drawing seems to anticipate the conventions of the snapshot.

He later commissioned daguerreotypes himself, four of which, Calasso tells us, were found in a drawer of his desk “a few years ago.” One of these—the most startling image in the book, and chosen for the cover of the UK edition (the Americans chickened out and substituted Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio)—shows a lost painting on its easel, apparently depicting his first wife, Madeleine Chapelle, lying naked, on her side but somehow full-frontal, a painting as erotically direct as Manet’s Olympia and yet “closed in.” “One might say that Ingres was aiming to eliminate nothing less than space itself.”

The painter and illustrator Constantin Guys was picked by Baudelaire from out of the chorus line, as it were, to stand as the spirit of modernity. Even today the choice strikes many people as mysterious—Guys was not a genius. But that was part of Baudelaire’s point; Calasso notes that vulgarité and modernité have an entwined history. Furthermore, Guys’s light, rapid sketches did not simply evoke photography, but leaped forward to cinema. “Guys was a harbinger of Max Ophuls rather than Manet.” He enjoyed the freedom of a déclassé form: “illustrators tended to be more daring than the painters of their times.”

Meanwhile, Gautier thought that what Baudelaire “loved in those drawings was the complete absence of antiquity, that is to say the classical tradition, and the profound sentiment of what we shall call decadence.” And then Gautier goes on to explain, citing a passage of Baudelaire’s that contrasts styles in women’s self-presentation, how the classical order stood for unmolested nature while decadence, or modernity, denoted a highly studied and self-conscious effect. Which in turn sounds like everything that Guys was not, but that perhaps only reflects how many times the seesaw of nature and culture has rocked over the interval between their time and ours.

Calasso’s secondary, almost submerged subject is in fact women, who present problems for all these men, in a panoply of ways. For Baudelaire, haunted by his mother and by his indifferent mistress Jeanne Duval, woman was “a terrible and incommunicable being like God,” whose self-adornment was an appropriation of nature that male mortals could not challenge. But he was far from the strangest in his views. Consider Degas, almost blind, who “seemed to have moved his eyes to his fingertips,” and yet was a “voyeur without sensuousness,” about whom Félix Fénéon could say that he “devotes to the female body an ancient animosity that resembles rancor.” Renoir may have said, “I paint with my prick”—but not Degas, “because an invisible Jansenist lash stood between him and every female body.”

But the Jansenist lash alone does not explain his Medieval War Scene, a bizarre tableau that evokes no one so much as the “outsider” painter Henry Darger. It shows, in a generic countryside, a trio of elegant Renaissance horsemen delivering parting arrows at a group of nine naked and tormented women, some of whom are lying as if already hit although there is no trace of blood. The women are “things that can be disposed of.” No historical anecdote has ever turned up to explain the scene. The painting is cruel, formalized, indifferent, whimsical. The only way to look at the picture other than as simply an expression of extreme misogyny is to focus on the repertoire of neoclassical poses it displays. And yet Degas gained his fame precisely for “his complete abandonment of canonical poses.” Was he, then, equating women with nature, and nature with classicism, and pantomimetically exterminating the dead past by electing naked women as his proxies?

Degas was in any event a vast pile of unresolved contradictions, and surprising strengths and weaknesses, of all sizes. He was far and away the finest photographer among the dabblers of his generation, rigging up complex tableaux and carefully posing his subjects to achieve a convincing effect of freshness and spontaneity. He had the acuity to sum up Mallarmé’s ideas in a phrase: “[Words] have enough strength to resist the aggression of ideas.” Observing the fin-de-siècle “progressive aestheticization of everything,” he drily noted, “We must discourage the fine arts.” But he became a raging and conspiratorially-minded anti-Semite, partly, it seems, as a consequence of allowing his housekeeper to read to him from Édouard Drumont’s virulent La Libre Parole (in the process breaking with the Halévy family, who had been his closest friends), and ended his days, during World War I, as an unkempt and ceaselessly wandering old man, all but a vagabond.

According to Mallarmé, Baudelaire, an “enlightened amateur…our last great poet,” had understood Manet’s work before it even existed, although he did not live to see it. Mallarmé went on to characterize Manet, who for Calasso embodies “painting itself,” as “singular because he abjures singularity,” while Degas said of him that “he is not an artist by inclination, but by force of circumstances. He is a galley slave chained to his oar.” Manet, who experienced his eureka moment at the Prado, noticing how Velázquez’s subjects were “enveloped only in air,” was too simple not to be misunderstood. He was labeled an Impressionist, although it often seems as though he was anything but, and then the public of his time underwent a collective failure of understanding and imagination in the face of his Olympia. They laughed, thought she was filthy, described her as a “female gorilla,” reacted with “a blend of derision and intense curiosity.”

Calasso avers that the reason the painting caused the scandal it did “has yet to be identified.” To a large extent that reason must have been socially determined—her unaffected erotic realism, as opposed to the mystique in which the grandes horizontales of the period were still enveloped, was perhaps too great a shift in class attitudes, seventeen years before Zola’s Nana.1 Calasso downplays that approach, but suggests the shock came from the intense frontal lighting, “as if for a moment Weegee’s lens had superimposed itself over Manet’s eye.”

“After Victorine Meurent, the model for Olympia and Déjeuner sur l’herbe, vanished in America, Manet felt lost,” writes Calasso. For a moment, a great epic suggests itself—I found myself imagining her as Claudia Cardinale’s character in Once Upon a Time in the West—but actually no such thing occurred. (Meurent continued posing for others, including Toulouse-Lautrec, became a painter herself—a good one, to judge by the sole surviving example of her work—and settled down with another woman in the Parisian suburb of Colombes. She died in 1927.)

Calasso’s work can resemble a cabinet of wonders, and some of his transitions verge on sleight-of-hand. His free-associative method can provide some wonderful side trips, such as his account of the vexed relationship between Manet and Berthe Morisot—a relationship that was starved in life but blossomed in painting—which connects to the main theme largely on the basis of an incidental resemblance between a Manet portrait of Morisot and one he made of the aging Jeanne Duval.

Although the book relates arguments old and new, it does not really make an argument of its own. Although Calasso’s method can resemble Walter Benjamin’s, he is not attempting to resolve the conflict between the social and the spiritual. Although he can be reminiscent of Borges, he is not pretending to part the veil of ancient mysteries. Although his memory might seem to work a bit like W.G. Sebald’s, it does not come with the promise of intimacy. He is prodigious, smooth, intimidating, a spellbinding monologuist.

La Folie Baudelaire is the sixth of Calasso’s series of book-length essays, the others of which have centered on Talleyrand, Greek and Indian mythology, Kafka, and Tiepolo. He is also a publisher, the head of the Milan-based house Adelphi. In a New Yorker profile of Calasso, Andrea Lee quotes his introduction to a collection of the house’s risvolti, or jacket blurbs, all of which he has written himself:

What is a publishing house, if not a long serpent made out of pages? Each segment of the serpent is a book. Or one could see that series of segments as a single enormous book, a book that contains many literary forms, many styles, many periods, but which continues, calmly, to go forward, adding on new chapters, which are books by different authors. A perverse and polymorphous book.2

With a little cutting, this could serve as a description of Calasso’s own books, which might as well be a single, polymorphous, hydra-headed book, perhaps intended to add up to an ongoing portrait of civilization. La Folie Baudelaire is a richly diverting, formidably learned work that sets the reader’s mind off on a thousand tangential explorations but does not, for all of its verve and its promiscuity of connection, really go anywhere in particular. It is circular, a fireside chat, a jeux d’esprit, a benevolent provocation. But maybe it will take further installments of Calasso’s project for the series to snap into focus as a self-portrait, rather like those giant digital heads that turn out to be made up of hundreds or thousands of small pictures.

This Issue

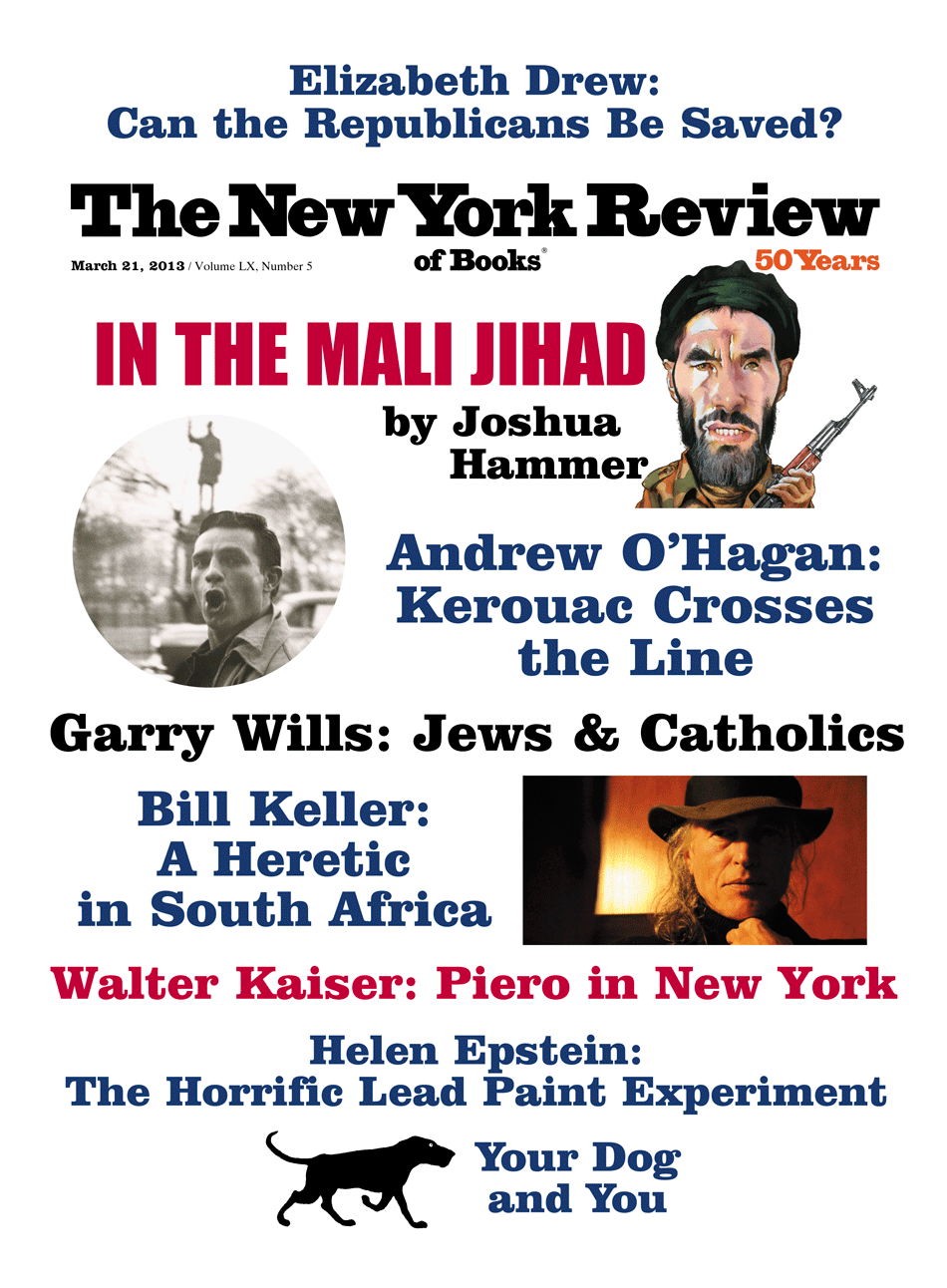

March 21, 2013

When the Jihad Came to Mali

Homunculism

The Noble Dreams of Piero