A generous selection of Longfellow’s poetry, edited by J.D. McClatchy, is available from the Library of America; a scanned edition of James Russell Lowell’s poems is ready for your Kindle; and Honor Moore makes her case for Amy Lowell in the American Poets Project series. But we don’t read these poets anymore, not really. Some people read Edna St. Vincent Millay still, but probably most would be convinced by Edmund Wilson’s portrait of her as a romantic figure who by the 1940s had outlived her moment of outrageousness. There are a multitude of reasons why a writer goes out of fashion, which isn’t always the same as being forgotten. Longfellow, these two Lowells, and Millay remain names in American literature, even if their work isn’t read outside of specialist circles.

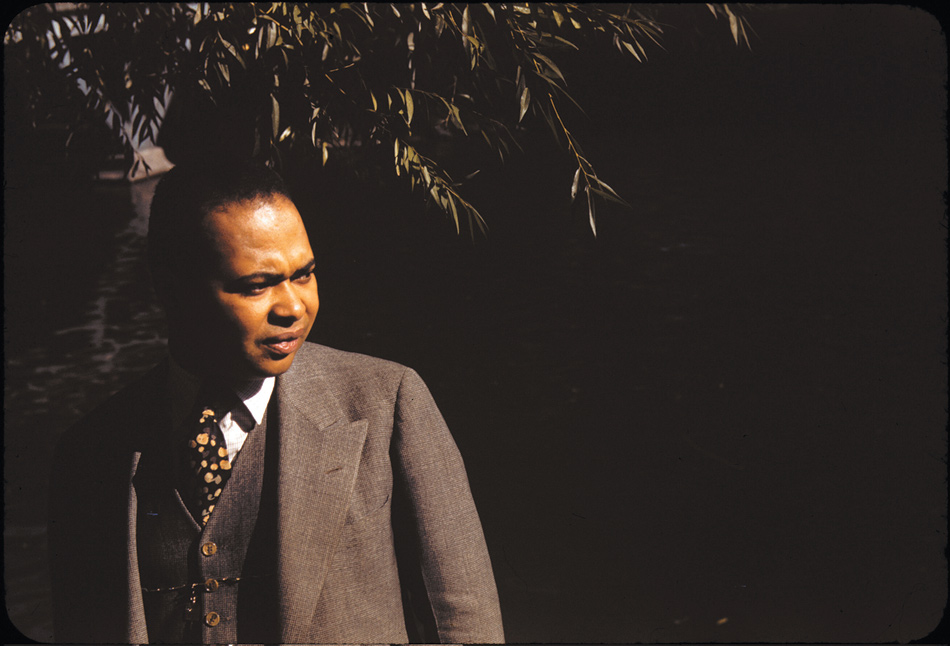

Similarly, Countee Cullen is part of Negro heritage. Last year, at the dedication ceremony of the Harlem branch library named for him, schoolchildren recited his poetry and a bust of him was unveiled. Some old-timers pronounce his name “Coun-tay,” as he did, rather than “Coun-tee.” He belongs to his period, the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance, those days of hopeful migration from the South and race pride given new voice in the North:

What is Africa to me:

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

Women from whose loins I sprang

When the birds of Eden sang?

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me?

(“Heritage”)

Cullen’s work is African-American literature, his cultural setting one in which the serious treatment of racial subjects by black writers was considered a breakthrough, liberation from the minstrel tones that white authors had for so long represented as the black voice in American literature. Cullen is seen most sympathetically in a literary tradition that places propaganda value on the fact of black composition. That a black youth, brought up partly in Harlem, was writing poetry was taken as a stand against oppression, regardless of the actual content of his poems. White American society did not expect or encourage a black youth to have larger aspirations. However, Cullen himself asserted early on that he wanted to be a poet, not a Negro poet. “Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:/To make a poet black, and bid him sing!”

Countee Cullen’s poetry was celebrated in the 1920s as a demonstration of his discipline with form and of his happy immersion in English Romantic poetry. Jazz Age Harlem was proud that a black youth had mastered English prosody, in a manner not so far removed from the example of Phyllis Wheatley, the eighteenth-century prodigy in Boston, whose strict rhymed couplets were taken as proof that a black was capable of high verse. Wheatley wrote as a Christian and an American patriot, and gave little clue about what sense she had of herself as an enslaved African.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips—“Another of those names that straddles seas in the sails of unseen/Ships,” he says in a poem from his debut collection, The Ground—is a young Caribbean-American poet and translator from the Catalan. He argues in his recent essay collection, When Blackness Rhymes with Blackness (2010), that twentieth-century black poetry began with the late-nineteenth-century career of Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906) and his “bifurcated sensibility.” Dunbar wrote a considerable amount of skilled poetry. However, the demand for his dialect poems about rural black scenes was far greater than that for his poems on conventional themes written in what was called “standard” English, a situation that tormented him. “We wear the mask that grins and lies,” one of his most bitter poems begins. The critic J. Saunders Redding said, in his groundbreaking literary history, To Make a Poet Black (1939), that Dunbar’s dialect poems were written in a synthetic language, a regional parody that his Northern audience understood easily and found entertaining:

G’way an’ quit dat noise, Miss Lucy—

Put dat music book away;

What’s de use to keep on tryin’?

Ef you practise twell you’re gray,

You cain’t sta’t no notes a-flyin’

Lak de ones dat rants and rings

F’om de kitchen to be big woods

When Malindy sings.

(“When Malindy Sings”)

But Dunbar didn’t make the speakers in his dialect poems ridiculous for the sake of entertainment. More often he manages quite the opposite. His speakers convey a melancholy innocence that becomes the tone of black life itself:

Oh, I hugged him, an’ I kissed him, an’ I baiged him not to go;

But he tol’ me dat his conscience, hit was callin’ to him so,

An’ he could n’t baih to lingah w’en he had a chanst to fight

For de freedom dey had gin him an’ de glory of de right.

So he kissed me, an’ he lef’ me, w’en I ’d p’omised to be true;

An’ dey put a knapsack on him, an’ a coat all colo’ed blue.

So I gin him pap’s ol’ Bible f’om de bottom of de draw’,—

W’en dey ’listed colo’ed sojers an’ my ’Lias went to wah.

(“When Dey ’Listed Colored Soldiers”)

The question Cullen asked about how to be a poet without being a black poet perhaps makes him one of Dunbar’s legatees in what could be described as “the performance of race.” Both regarded race as a difficulty, the great obstacle in their way, especially since the curious thing on Cullen’s mind seems to have been the contradiction between the cruelty of the black condition and the higher concerns the poetic sensibility was supposed to lead him to dwell on.

Advertisement

Racism was a tyrant deforming black creative life, dictating black writers’ subjects. Yet perhaps J. Saunders Redding had it right, after all, when he observed that Paul Laurence Dunbar was not something new so much as he was the culmination of a style or school. He was better at dialect poetry than anyone else around and handled with grace an idiom that is cringe-making in most poets of the period, white and black. Dunbar died young, and with him the plantation mood in African-American literature.

The black lyric poets after the Reconstruction generation and immedi- ately preceding Cullen, such as Wil- liam Stanley Braithwaite—“My Thoughts Go Marching Like an Arm- èd Host”—and Georgia Douglas Johnson—“I Want to Die While You Love Me”—freed their work of the church and, in some cases, of the South. Johnson might hope that God’s sun would shine someday on a perfected and unhampered people, but her poetry can also speak of a desire for an individualism away from God and history. “I believe that the rhythmical conscience within/ Is guidance enough for the conduct of men,” ends Johnson’s “Credo.” Individual consciousness fought the added burden of race consciousness. Lament was the tone this generation tended toward, a consequence of its members’ gentility as black people of letters. Before he taught creative writing at Atlanta University, Braithwaite was for three decades literary editor of The Boston Evening Transcript, and for as long Georgia Douglas Johnson held a polite salon in her Washington, D.C., home.

This generation rejected dialect and few distanced themselves from minstrel-era associations more vigorously than James Weldon Johnson. In his important anthology, The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), he dismissed dialect as too restrictive in its emotional possibilities for what the modern black poet had to say. Older than the poets associated with the Harlem Renaissance, he is a transitional figure between the genteel tradition and the triumph of the vernacular. He turned away from dialect, but did not look up to the heavens. He identified with the aims of the younger generation. Just as in the late 1960s Gwendolyn Brooks’s poetry changed significantly after her encounter with the young poets of the Black Arts Movement, so Johnson was influenced by the New Negro aesthetic—the emphasis on identifying with black vernacular culture—in his collection God’s Trombones (1927), a series of connected poems in which he tries to convey the musicality of the black church service.

Zora Neale Hurston complained that white people were making money from popular or low black culture while black artists were wasting their time trying to be highbrow about their sufferings. But the historical moment belonged with the vitality of the material that young black artists such as Hurston and Langston Hughes drew from the experiences of the masses, of their rural Southern black culture transformed in the urban North. Some black novelists and short-story writers of the Harlem Renaissance embraced the freedom that dealing frankly with this suddenly visible and audible black life gave them, but by no means all.

For instance, where Wallace Thurmon’s satires were considered risqué, Jessie Fauset concentrated on the plight of middle-class black women and most black novelists wrote sober problem novels. Fewer black poets were persuaded to join the Negro Awakening at the point where they were called on to express their dark-skinned selves unapologetically and unabashedly, as Hughes urged in “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” an essay of 1926 that has come down to us as the manifesto of the Harlem Renaissance, but most, like Cullen, wrote in standard English.

Claude McKay, another Harlem Renaissance figure, is unusual in that he found a lively, personal idiom for the black working-class characters of his fiction, while his sonnets of militant racial protest adhered to the language of his English poetic models. Countee Cullen also never tried to inflect with a personal idiom the historical poetic language he’d been taught—the language of the metaphysical and the Romantic poets. But unlike McKay, he was not a radical and didn’t have his reputation for taking a confrontational tone in his work.

Advertisement

Indeed, everybody knew that Countee Cullen was the young black poet whom Langston Hughes had in mind when he charged that a black poet who said that he didn’t want to be a black poet was in effect saying that he wanted to be white. In Hughes’s view, race was not an obstacle to the transcendent, it was the most profound of subjects, and black culture excluded nothing. When Hughes published “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” he and Cullen were both rising stars, regarded as maybe different in approach, but involved in the same struggle, the advancement of the black race.

Yet time has not been generous to Cullen. If Dunbar’s poetic legacy marks a division between poetry about black life in an imagined black idiom and a poetry seeking universality by being color-blind, then Cullen is on the losing side. In his poem “To Certain Critics,” published in The Black Christ and Other Poems (1929), he wrote:

Then call me traitor if you must,

Shout treason and default!

Say I betray a sacred trust

Aching beyond this vault.

I’ll bear your censure as your praise,

For never shall the clan

Confine my singing to its ways

Beyond the ways of man.No racial option narrows grief,

Pain is no patriot,

And sorrow plaits her dismal leaf

For all as lief as not.

With blind sheep groping every hill,

Searching an oriflamme,

How shall the shepherd heart then thrill

To only the darker lamb?

The reluctant lamb of Negro heritage kept the facts of his early life to himself, maybe because he was illegitimate and his family impoverished. He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, most likely in 1903. The 1910 census suggests that he was living in New York with his paternal grandparents and school records thereafter indicate that he moved around a lot. Charles Molesworth in And Bid Him Sing: A Biography of Countée Cullen, the first full biography of the poet in some time, adds that Cullen’s grandmother was so obese she was too embarrassed to leave her home. She took care of foster children in her Harlem apartment after Cullen’s grandfather died in the beginning of 1917, but she did not survive him long. Her death at the end of that year left Cullen a sort of orphan. There seems never to have been a possibility of a parent taking him back. His mother lived until 1940 and Molesworth explains that, although he never went to see her, Cullen as an adult sent her a monthly allowance. He traveled to Louisville to attend to her funeral arrangements himself. He’d told hardly anyone about her.

What Harlem knew was that he was the adopted son of Reverend and Mrs. Frederick Cullen of the Salem Methodist Epsicopal Church, one of the largest in Harlem. He went to live with Reverend Cullen in 1917 and stayed with him for almost thirty years. Molesworth tells us that Cullen looked back on what he called “the conservative atmosphere of a Methodist parsonage” and observed that his chief problem in life had been “reconciling a Christian upbringing with a pagan inclination.” Reverend Cullen’s sense of civic mission was intense; nevertheless rumors persisted about “the use of his wife’s makeup and undue attention to the choirboys.” The civic mission at nearby Abyssinian Baptist Church featured anti-homosexual crusades led by its pastor, Adam Clayton Powell Sr. Molesworth concludes that it’s impossible either to prove or to disprove such century-old gossip. But Cullen himself, as Molesworth makes clear, became drawn to men.

To be a son of such a prominent church provided Cullen with a proper identity, Molesworth goes on to say, just as the discovery that he was a gifted student began to place his name in the historical record. In 1918, Cullen entered prestigious DeWitt Clinton High School where his classmates included Barnett Newman and Lionel Trilling. (James Baldwin would also attend DeWitt Clinton some twenty years later, after having had Cullen as his junior high school French teacher.) Cullen joined the school literary magazine and won a citywide poetry contest for high school students, the first of several poetry prizes that he received as he moved diligently through an excited education. He went to New York University in 1922 on a full scholarship, graduated three years later with honors, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He pursued a master’s degree at Harvard, but even as he sat before George Lyman Kittredge, Bliss Perry, and Robert Hillyer, Cullen was already a published poet. A friend reported to Cullen that he’d heard Robert Frost saying nice things about him.

Color, Cullen’s first poetry collection, appeared to wide favorable notice in 1925, a volume mostly of lyrics in the tradition of high verse, as Molesworth characterizes it: “Love, leave me like the light,/The gently passing day…” (“If You Should Go”). Color also contains the poems about race that have been his most anthologized pieces, though he may not have wanted it that way. Molesworth interprets a long poem, “The Shroud of Color,” sometimes cited for its bleakness about race, as being actually redemptive in meaning. Cullen joins the despair of his racial identity with belief in Christian suffering, “the cries of all dark people” who speak through him. Molesworth identifies what for him are the significant tensions that run throughout Cullen’s work: “whether or not to write in the mode of uplift; whether one’s identity as a poet must be racialized; what audience, white or black, is it most proper to address.”

Copper Sun, Cullen’s second collection, appeared in 1927. Its subjects mostly have to do with romantic love and religious faith. But once again, it contains one of his racial poems that made an impression back then, “From the Dark Tower” (“We shall not always plant while others reap”). Caroling Dusk, an anthology of verse by forty Negro poets that Cullen edited, not an anthology of Negro verse, he insisted, also came out in 1927.

The Black Christ and Other Poems followed in 1929. The long undistinguished title poem is a narrative about the victim of a lynch mob who has a vision of Christ and is then resurrected. This collection did not have the success of his first two volumes. Very soon Molesworth is writing about the last collection Cullen would publish in his short life, The Medea and Some Poems (1935), and coming up with explanations for his falling off, for the lyric impulse having deserted him.

The Depression overtook the Harlem Renaissance very quickly. Before the stock market crash, Cullen had won a Guggenheim and maintained a lively column primarily on the arts in Opportunity, the magazine of the Urban League that had been a showcase for the new generation of black writers. He published a novel, One Way to Heaven (1932), that was in part satirical of the black church. But in the early 1930s, Cullen was living close to the poverty line. He declined an offer from a black college in the South in order to remain in New York to care for the ailing, widowed Reverend Cullen. He was wary of life under Southern-style Jim Crow anyway. In 1934 Cullen found employment as a teacher in the New York City public school system, and he continued until his death in 1946. “Imperceptibly but inevitably” he became “more a schoolteacher than a poet.” In the last decade of his life, Cullen wrote half a dozen poems, Molesworth notes.

He nourished ambitions in the theater, starting with an adaptation of Euripides. Cullen had done well in his Greek class his first year at NYU, but Molesworth is not certain how much Greek he knew. He tried his hand at radio scripts and Molesworth discusses several works for the stage, drama and librettos, either unfinished or not put on. “If he had had better luck in getting these works staged, he would have become known as a playwright concerned with race as the central problem of his time.” He collaborated with Arna Bontemps on St. Louis Woman, a musical based on a Bontemps novel. It had to wait years to find a producer and it finally had a theatrical success. However, it opened a few months after Cullen’s death.

When Cullen died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1946, at the age of forty-three, W.E.B. Du Bois mourned his promise: “Cullen’s refusal to accept race as a basic and valuable segment of his total identity was an evasion which prevented him from further straightforward and clear development.”

Molesworth defends Cullen against such charges, arguing that he held “somewhat nuanced views about race and art”; that “Cullen’s attitude and commitment on these issues tended to be more complex and nuanced than those of many others”; that “being called ‘a Poet First And a Negro Afterward’ reduced to a crude slogan the troubled and nuanced sense that Cullen had lived with for some years”; that his second volume is “replete with evidence of Cullen’s complex and nuanced feelings about a range of subjects.” Molesworth seeks to rehabilitate Cullen, to rescue his “singular genius.” He goes to some lengths to assert the racial awareness of Cullen’s poetry and prose, as though he had become a symbol in African-American literature for the escapism and impotence of “pure art.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, forms of poetry were sometimes discussed as though they had racial affinities and Cullen’s use of rhyme and choice of stanza form were dismissed as somehow white. Formal was white; free verse was where it was at. But in the 1960s, Robert Hayden faced the same accusations from black nationalist poets that he was too white in his work. The charges were never going to stick, not only because of Hayden’s memorable poems concerning black history, such as “Middle Passage” and “Runagate Runagate,” but also because he was a truly superior poet and could do what Cullen could not. The reason Molesworth concentrates on Cullen’s poetry with racial themes is not only because he wants to remind us that Cullen did not evade the subject, but also because not much of a case can be made for his love poetry or his religious poetry.

While Cullen confessed his ambivalence in having to write about race as his particular experience, he also expressed strong opinions about how race should be approached. He was on the side of Du Bois and other older black critics in their disapproval of what they saw as depictions of Harlem as libidinous and indecent. He was against the preachiness of uplift in black literature, but he believed in decorum on the page. He was no more in sympathy with the vernacular than Du Bois. He also believed in secrets, he said. Alain Locke, a champion of his younger work, judged that what caused Cullen’s talent to dim was “not the decline of technical power but a personal retreat from the world of significant outer experience without any compensatory opening up of a world of internal experience.” Locke had known him well and must have known what those inner pressures were.

Cullen was married twice. His first wife was Du Bois’s only daughter and their wedding in 1928 a high Harlem affair. They divorced within eighteen months, after he told her about his involvement with men. Cullen’s second wife, whom he married in 1940, suffered a miscarriage in 1945. They were close, but “married life did not eliminate his attraction to men, and he carefully and discreetly maintained a long intimate attachment to Edward Atkinson [an actor].”

Molesworth does not read the poems too far in relation to the men in Cullen’s life or make much of the tension that Cullen himself said he felt because of the conflict between his church upbringing and his desires. In Carl Van Vechten’s “circle of homosexual friends,” of which Cullen was a part, “gossip served as root and branch.” However, Molesworth doesn’t treat Cullen’s milieu of black boys about town as a strong element in his creative and emotional life, as Emily Bernard does in her recent Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White (2012). He seems more at ease talking about Cullen’s epistolary flirtation with, say, Dorothy West, a young black writer.

Cullen’s poems had received notice since his undergraduate days. He came of age in an atmosphere of praise. How he handled the unfair questions of his time as a black artist makes him of historical interest, not of literary importance, and to say so is not an insult. Similarly, Cullen, like Stephen Spender, has renewed life as part of gay history, in the work of queer theorists such as Mason Stokes and social historian Michael Henry Adams, who is at work on a book about the gay Harlem Renaissance.

Cullen had been at his most fulfilled in Paris, which he first saw in 1926. He fell in love with the city, where he lived almost entirely in the black expatriate community, and went back every year until 1939, often in the company of Reverend Cullen and the dashing Harold Jackman, who’d twice been his best man. Yet of the ambivalences that shaped Cullen’s life, perhaps the most fundamental was the agony of exposure that publication meant for someone so recessive. None of Cullen’s books was in print at the time of his death.

This Issue

March 21, 2013

When the Jihad Came to Mali

Homunculism

The Noble Dreams of Piero