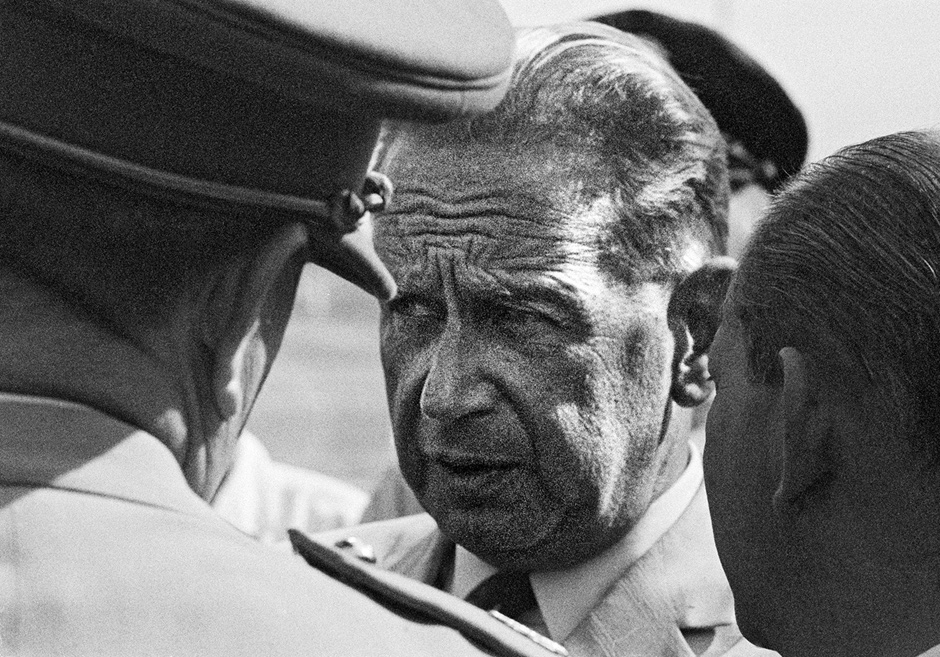

When Dag Hammarskjöld’s body was recovered from the crash site in Ndola, Zambia, where the Albertina, his chartered DC-6, went down on the night of September 18, 1961, he was lying on his back, propped up against an ant hill, immaculately dressed as always, in neatly pressed trousers and a white shirt with cuff links. His left hand was clutching some leaves and twigs, leaving rescuers to think he might have survived for a time after being thrown clear of the wreckage.

Searchers also retrieved his briefcase. Inside were a copy of the New Testament, a German edition of poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, a novel by the French writer Jean Giono, and copies of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s I and Thou in German and English. Folded into his wallet were some copies of American newspaper cartoons mocking him, together with a scrap of paper with the first verses of “Be-Bop-a-Lula” by Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps.

Searchers also recovered some sheets of yellow lined legal paper filled with his minute, neat—some called it Japanese—handwriting. This enabled investigators to conclude that in flight he had been working on a translation of Buber’s I and Thou. There is a photograph of the Jewish prophet and the spry Swede taken together in Jerusalem in 1958. Hammarskjöld liked quoting Buber’s apodictic remark: “The only reply to distrust is candor.” In a jolting aircraft traveling through the night sky over the African jungle, the secretary-general devoted his final moments alive to turning Buber’s difficult thoughts into English:

This is the exalted melancholy of our fate that every Thou in our world must become an It.

Any reckoning with Dag Hammarskjöld’s life has to begin in Ndola. Clues to his elusive inner life were strewn across the crash site and the crash itself has never been conclusively explained. His colleague and first biographer, Brian Urquhart, blamed the crash on pilot error and dismissed the conspiracy theories that had sprung up around his death, but the new biography by Roger Lipsey gives considerable attention to the possibility that he was murdered.

Zambian charcoal burners working in the forest near the airport that night, and interviewed by a succession of investigators in the years since, have always claimed they saw another plane fire at Hammarskjöld’s aircraft before it plunged to earth. In 2011, a British scholar, Susan Williams, reignited the debate over his death in a book entitled Who Killed Hammarskjöld?1 On the basis of extensive new forensic and archival research, she speculated that the mystery plane might have been a Belgian fighter aircraft working for the Katangese rebels. Hammarskjöld had plenty of enemies: white racist Rhodesians opposed to his support of African liberation; Belgian mining interests aligned with the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga that the UN was trying to bring to heel; the CIA and the KGB, each battling for control of Congolese factions and each opposed to Hammarskjöld’s overall goal of letting the Congolese decide their own future for themselves. Williams’s work establishes plausible motives for murder but does not actually prove that it was one or, if so, who was responsible.

In 2012, a panel of retired jurists, including Judge Richard Goldstone and Sir Stephen Sedley, was commissioned by a committee of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation in Sweden to review the evidence about his death once again. Apparently the foundation wants to keep its distance from the inquiry. The commission reported in September of this year, and after extensive review of previous investigations and on-site interviews with witnesses, including the now aged charcoal burners, it found that there was sufficient evidence to warrant a new UN investigation into whether Hammarskjöld’s plane was fired upon or forced down before it crashed.2

The truth may lie in the archives of the US government. The CIA and the National Security Agency maintained a listening center in Cyprus that, according to former employees, was tracking the plane’s approach to Ndola.Researchers have already filed freedom of information requests to gain access to these air-traffic intercepts, but it remains uncertain whether even they will resolve what happened that night at Ndola.

While the mystery of Hammarskjöld’s death awaits resolution, Roger Lipsey’s new biography makes an elegant and highly informed attempt to unravel the mystery of his life. He was at once a secular power-player and Christian philosopher, an earnest mystic and a Machiavellian man of action. The challenge is to find how these parts of a complex personality cohere. Lipsey does not try to compete with Brian Urquhart’s magisterial biography of the public man. Instead, he has provided us with a revealing map of the bleak but exalted landscape of Hammarskjöld’s inner life.

Advertisement

Throughout his career, the shy, understated Swede, who never married, who once showed a female journalist around his New York apartment with the wry words, “Monastic enough for you?” and kept everyone guessing about his sexual orientation, eluded easy definition or media capture. No one suspected, when he was chosen for the job in 1953, that he would turn out to be the secretary-general who more than any other came to incarnate in life and death the soul of the UN as an institution.

In the 1920s and 1930s, he struck his Swedish contemporaries simply as a reserved and ambitious young man seeking to measure up to a father who had been a principled and unpopular prime minister of Sweden between 1914 and 1917. His mother, on the other hand, gave him unstinting love and introduced him early in life to the Christian devotional literature that became his constant companion. The young Hammarskjöld was trained as an economist and during Sweden’s ambiguous neutrality during World War II held important posts in the central bank and finance ministry. After the war, he became a minister of state for foreign affairs in the Swedish Foreign Ministry. It was there that chance and fate found him in 1953 when the big powers were looking for a new head of the UN.

It was the British, in fact, who picked him out of the list of compromise candidates to replace Trygve Lie as secretary-general, when it became apparent that the Soviets would block Lester B. Pearson of Canada, the most visible candidate. Anthony Eden, the British foreign minister, had met Hammarskjöld at meetings on European postwar reconstruction and suggested his name, assuming that the quiet Swede would give Her Majesty’s government no trouble.

He inherited an organization poisoned by the acrimony of the cold war. The FBI was roaming through the UN building, investigating Senator Joseph McCarthy’s wild allegations that American Communists had infiltrated it. For more than three years, the Soviet Union had boycotted the UN, because of Trygve Lie’s robust support for US-led intervention in Korea. Hammarskjöld’s first task was to get the FBI out, get the Russians back in, and restore the organization’s shattered morale.

He accomplished all three tasks within the first year, but this period of his life was shadowed by malicious rumor. Trygve Lie, angry at being denied a second term and jealous of Hammarskjöld’s sudden ascent, lent himself to a nasty campaign of insinuation about Hammarskjöld’s sexuality. This was a time when such whispers could ruin a life. Homosexual conduct was still a crime and only a year later Alan Turing, the British pioneer of computer science, would commit suicide after being convicted for a homosexual act and being forced to submit to chemical castration. Hammarskjöld maintained a dignified silence during the whispering campaign about his own sexuality and managed eventually to put the rumors to rest without abandoning his solitary bachelor existence or surrendering his privacy. The whispering campaign could only have deepened his isolation and loneliness. He came through the ordeal with what Margaret Anstee, who worked with him in those years, called “iron single-minded will” and a “unique kind of dignity.”3

His first years were blessed with geostrategic luck. Stalin died weeks before his selection, Senator McCarthy and his threat to the UN went into eclipse, and between 1953 and 1956 there was a lull in the cold war that enabled Hammarskjöld to revive and rebuild the institution.

In his seven years as secretary- general, he astonished those who predicted he would be nothing more than a genial Nordic cypher. He transformed the role of the secretary-general from the Security Council’s executive director into an independent international problem solver, with immense if fluctuating moral authority. He professionalized the UN civil service, giving it an esprit de corps and an independence from national governments. He pioneered UN peacekeeping and did more than any secretary-general, before or since, to articulate what the UN should stand for.

Lipsey portrays Hammarskjöld as a saint, mystic, and visionary but underplays his intensely political side. He had a far-seeing geostrategic imagination and he was nobody’s fool. In a fascinating letter to Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion written in 1956, he said bluntly:

Please do not believe that I permit myself to be taken in by anybody, but realize, on the other hand, that I cannot work on the general assumption of people trying to double-cross me even when this runs counter to their own interest.

In the same secret exchange, he took issue with Ben-Gurion’s conviction that blunt force was the only way to secure Arab respect:

You believe that this way of creating respect for Israel will pave the way for sound coexistence with the Arab peoples. I believe that the policy may postpone indefinitely the time for such coexistence.

This was about as moralizing as he ever got. He was too shrewd a politician to believe that lectures would have leverage over politicians’ ambitions or states’ vital interests. He was especially realistic when it came to the permanent five on the Security Council. Wherever their vital interests were at stake—Hungary and Poland in 1956 for the Soviet Union, Tibet for China in 1959, and the Latin-American backyard for the Americans—he kept silent and accepted that the UN would be sidelined.

Advertisement

As soon as he saw an opportunity, however, he knew how to throw the UN into the thick of the action. The best example was the Suez Crisis of 1956. The abortive Anglo-French attack on Suez, followed by the Israeli seizure of Sinai, created a situation in which everyone—the British, the French, the Israelis, the Americans—needed a way out. Hammarskjöld seized on Lester B. Pearson’s idea of deploying a UN force to keep the parties apart and drove the UN Secretariat to organize and deploy the force with amazing speed and success. Ably assisted by Ralph Bunche, who had negotiated the end of the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, and by Brian Urquhart, who had seen active service with the British military and could provide expert advice on planning and development, Hammarskjöld led the UN into the new era of peacekeeping.

The biographer’s challenge is to figure out how Hammarskjöld’s secret inner life made possible his complex public achievement. The key to that inner life is a small diary, found after Hammarskjöld’s death on the bedside table of his apartment on East 73rd Street in New York, neatly typed out and apparently ready for publication. When the diary appeared posthumously in 1963 with the title Markings, it caused a sensation, some Swedish journalists sneering that it revealed Hammarskjöld’s Christ complex, others his closet homosexuality. Actually, it did neither. As Lipsey shows, Markings is a classic work of devotional mysticism in a tradition going back to Blaise Pascal’s Pensées et Opuscules and Thomas à Kempis’s Imitatio Christi. Markings takes the form of a series of dated diary entries that run from the 1920s right up to the eve of his death, written in gnomic, elusive, haiku-like forms that strive for effect yet escape pretentiousness because of their devastating candor. Markings reads like the self-scourging reflections of a desert mystic:

He is one of those who has had the wilderness for a pillow, and called a star his brother. Alone. But loneliness can be a communion.

Those seeking to understand Hammarskjöld’s sexuality, and why he seemed, in his friend W.H. Auden’s words, to be “a lonely man, not a self-sufficient one,” have pondered this entry in Markings:

You cannot play with the animal in you without becoming wholly animal, play with falsehood without forfeiting your right to truth, play with cruelty without losing your sensitivity of mind. He who wants to keep his garden tidy doesn’t reserve a plot for weeds.

Markings is also suffused with the glow of intense personal faith:

The light died in the low clouds. Falling snow drank in the dusk. Shrouded in silence, the branches wrapped me in their peace. When the boundaries were erased, once again the wonder: that I exist.

Or again:

God does not die on the day when we cease to believe in a personal deity, but we die on the day when our lives cease to be illumined by the steady radiance, renewed daily, of a wonder, the source of which is beyond all reason.

Lipsey is a patient, discreet, and compassionate guide to Hammarskjöld’s inner world. His previous work includes studies of Eastern and Western mystical thinkers, among them Thomas Merton; his biography of Hammarskjöld illuminates how the Christian mystical tradition became the secret source of Hammarskjöld’s life and thought. He knew the works of Master Eckhardt, Thomas à Kempis, and Jan van Ruysbroeck by heart and editions of their works were always at his bedside. Hammarskjöld’s spiritual search wandered far and wide but it always came back to his Christian roots. He had a horror of canting public displays of faith, but there is little doubt that he believed he was doing Christ’s bidding. Brian Urquhart found this note, written in Hammarskjöld’s hand, in his speech accepting a second term as secretary-general in 1957:

Hallowed be Thy name

Thy Kingdom come

Thy will be done

26 September 57

5:40

During his time as secretary-general, as he traveled the world, Hammarskjöld remained a seeker after truth, adding Buddhist, Chinese, and Japanese spiritual sources, as well as Martin Buber, to his personal book of common prayer. In the process he assembled an idiosyncratic personal synthesis of the world’s mystical traditions.

Henry Kissinger famously observed that the exercise of power is a process of depletion, in which you gradually use up every intellectual resource you originally brought to the task. In Hammarskjöld’s case, he seems to have deepened rather than depleted his inner intellectual resources during his time in the public glare. His cultural curiosity was omnivorous—from “Be- Bop-a-Lula” to Buber and beyond. He translated Djuna Barnes, arranged for Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night to be performed in a Swedish theater, and enjoyed the occasional dinner with the other famous Swedish recluse in New York, Greta Garbo.

Instead of reading out bland equivocations written for him by staff, he used his speeches to articulate the public philosophy of an institution that, when he took it over, was only eight years old. Not until Kofi Annan did any other secretary-general find the words for what the UN was trying to represent to the world. It was Hammarskjöld who wanted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony played on UN Day, who tried, in everything he wrote, to make the UN the voice for the human longing for unity, equality, peace, and justice. It was Hammarskjöld who said that the UN was “work[ing] for that harmony in the world of man which our forefathers were striving for as an echo of the music of the Universe.”

His mystic inner life served as a lonely man’s refuge from the pressures of office as well as a wellspring of that serene inner calm that made him so effective in a crisis. He could be uneasy and remote in his dealings with his staff, but his loneliness made him also awkwardly dependent on them and the “little republic” of the UN. He was blessed with truly extraordinary colleagues, the redoubtable Brian Urquhart as well as Ralph Bunche, the African-American who had won the Nobel Prize for negotiating the Arab-Israeli cease-fire of 1948. They were powerful personalities, but they didn’t mind taking orders from him. He seemed to have thought long and hard about what it was to exercise authority over others:

Your position never gives you the right to command. It only imposes on you the duty of so living your life that others can receive your orders without being humiliated.

His staff never saw him lose control or composure, not even during the Suez crisis of 1956, when after weeks of pressure and going without sleep, Hammarskjöld drove his team to deploy the first UN peacekeeping force in the Middle East. He could even be funny under pressure, as when he quipped to Bunche, once the peacekeeping force had been approved, “Now, corporal, go and get me a force!”

Lipsey’s biography raises the difficult question of whether it will be the public or the private man who will be remembered fifty years from now. Already Hammarskjöld the secretary-general is unknown to most people under fifty, and how many are aware of Markings?

Just as Marcus Aurelius’ public life has faded while the Meditations continue to be a source of Stoic wisdom, Lipsey believes we will remember Markings and forget the mission that drew him to his death at Ndola. I’m not so sure. His public career still matters, and it makes his inner life all the more remarkable.

As he flew to his death on that September night in 1961, Hammarskjöld was trying desperately to rescue the UN from the “Congo inferno,” a mission initiated in August 1960 to save the newly independent Congolese republic from dissolution and civil war. Hammarskjöld had marshaled nearly 20,000 military and civilian personnel, but by September 1961, the mission was in dire trouble. On the ground factional violence was flaring, while in New York the great powers were each accusing Hammarskjöld of backing the wrong side.

As the pressures mounted, his closest colleagues had never seen him so depressed. Just before he flew to Ndola, the UN’s representative in Katanga, the erratic Irish writer and diplomat Conor Cruise O’Brien had authorized an assault on the Katangese rebels that failed. This provided both the Russians and the Americans with further ammunition in their campaign against Hammarskjöld. After the UN attack on Katanga, the secessionist Katangese leader Moise Tshombe fled to nearby Rhodesia, then under the control of the British. When Tshombe—who had refused to cooperate with the UN—signaled that he was willing to meet the secretary-general in Ndola, Hammarskjöld seized on what he thought was a chance to negotiate the end of the Katangese secession.

He must have hoped his famed negotiating skills could not fail him. “Leave it to Dag” was a phrase of the time. Had he not negotiated with Zhou Enlai the release of US airmen from Chinese prisons in 1955? Had he not persuaded Nasser and Ben-Gurion alike to accept the UN peacekeepers? Had his diplomacy not helped Eisenhower to withdraw US Marines from their brief and ill-conceived landing in Lebanon in 1958? Why wouldn’t he be able to deal successfully with a Congolese renegade?

At the same time, he was anxious for a breakthrough. From the top-secret cable that he sent to Ralph Bunche on September 15, just before his death, we can see how truly hemmed in he was.4 Ralph Bunche was reporting from New York that President Kennedy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk were furious with the UN, worried that the Soviets were gaining influence in Africa at their expense. At the same time, Nikita Khrushchev launched a brutal public attack on Hammarskjöld’s neutrality and competence. Hammarskjöld had stood up to Khrushchev’s attacks, but privately he was admitting to friends that the “crazy” Congo mission was threatening to spin out of control and do fatal damage to the UN itself.

Perhaps when he flew to Ndola he was not so much optimistic as desperate. Whatever his motives, he paid for the gamble with his life, and the gamble—unusual and extreme for a man so dogged and disciplined—has raised a question about his judgment ever since.

In the Congo, he led the UN into a nightmare of great power rivalry, post-imperial chicanery by the Belgians, and lethal political score-settling by the Congolese politicians. He may have been naive to believe the UN could prevail in these circumstances. It did not help that he misjudged the abilities of his appointed representative, Conor Cruise O’Brien.

After his death, Hammarskjöld was so rapidly sanctified that the harder questions about his decision-making over the Congo were never asked. President Kennedy, who only days before had been furious at Hammarskjöld for his operation in the Congo, praised him as the “greatest statesman of our century.” Hammarskjöld’s successor at the UN, the Burmese diplomat U Thant, understood that the Security Council had grown tired of a secretary-general whose authority and prestige had begun to rival its own. Thant struggled in other ways to liquidate the failures of Hammarskjöld’s legacy.

The costs of the Congo operation nearly bankrupted the UN, and contributing countries like France and Belgium refused to pay the bill. By 1964, the UN had wound down the Congo mission and declared victory. It could claim that it had succeeded in averting full-scale civil war in the center of Africa; it had reintegrated the secessionist province of Katanga; henceforward Congo did not break into pieces. That, some of his defenders would claim, was Hammarskjöld’s legacy.

Yet with the passage of time, it has become clear that he had been mistaken to think the UN could bring order to the Congo. In the late 1960s and 1970s, it is true, there was order of a sort under the kleptocratic dictatorship of Mobutu. But once his thirty-year reign disintegrated, once Congo’s neighbors—Rwanda, Uganda, and others—sent troops in to support various factions and plunder Congo’s enormous resources, the country disintegrated once again.

The UN is still in the Congo, fifty years on. The great powers are only too happy to saddle the UN with Sisyphean burdens of stabilization that they are unwilling to shoulder themselves. From the first, the Machiavellian bargain at the heart of the UN has been that the organization takes a vow of silence when great power interests are in conflict and springs into action only when great power interests are aligned. Hammarskjöld accepted this bargain. He said nothing when the Russians marched into Budapest and crushed the Hungarian revolution. He said nothing when the Chinese crushed the Tibetan uprising in 1959. The US and the Soviet Union sidelined him in the Berlin crisis of 1961, but gave him the most thankless task of all, the Congo, and he died trying to save a country that their intrigues were pulling apart.

Just as in the 1950s, so now in 2013. The same Security Council that has been deadlocked over the catastrophe in Syria has nearly 20,000 troops in Congo. They include an “intervention force” of 3,500 with the mandate to defeat and disarm the chaotic and violent array of armed groups who have made murder, rape, sexual assault, and displacement of people a way of life in eastern Congo. What began with Hammarskjöld continues, and with just as much chance of success.

He did so much to define what the UN is that we can ask what he might make of an organization still sidelined in crucial conflicts and mired in the ones no one else will take on. It is an organization still disappointing to those who believe in it, yet still carrying the hopes of the diminishing number who believe that an interdependent world cannot do without a world organization.

For those who think of Hammarskjöld as the yearning and mystical idealist, it is hard not to believe that he would be deeply disappointed by what happened to his dreams. But there was always another Hammarskjöld, the disabused realist, the risk-taker who took the flight to Ndola because he thought it just might lead to a breakthrough. This Hammarskjöld would not be surprised at all at how the UN turned out in the fifty years since he boarded the flight that ended his life. For the world we have now—where violence contends with hope for peaceful change and the outcome is uncertain—is a world he understood only too well, and a world he cared about too much to allow him—or us—the easy escape of disillusion.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust

-

1

Susan Williams, Who Killed Hammarskjöld? The UN, the Cold War and White Supremacy in Africa (London: Hurst, 2011). ↩

-

2

See “New Inquiry into the Death of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld,” Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, August 6, 2012. The commission’s report can be read at www.dag-hammarskjold.com. ↩

-

3

Quoted in Stephanie Hegarty, “Dag Hammarskjöld: Was His Death a Crash or a Conspiracy?,” BBC News Magazine, September 17, 2011. ↩

-

4

See “Top Secret UN Cable 15 September 1961: Hammarskjöld Rejects American Criticism,” The Guardian, August 17, 2011. ↩