In the early 1870s, George Eliot looked back forty years to the England of her childhood; Middlemarch is a “historical” novel, all the more so because Eliot’s concerns are often with how the past has shaped the present. Lydgate, the doctor who marries so unwisely and whose hopes of making a contribution to medical science are consequently derailed, absorbs much of Eliot’s sympathy and exasperation—as does Dorothea Brooke, whose own hopes of contributing to human progress in social reform are also thwarted.

That our sense of Lydgate’s failure to make “a link in the chain of discovery” is his personal tragedy and not a large one for us all depends on our accepting Eliot’s positivist belief in the progress of science, and hence human society, that everywhere infuses this novel. Eliot can rely on the shared sense with her readers that things are “much better than they might have been” for us; progress in society, and the advancement of science, are inevitable. So it is that the spirits of the English reformers, and of Pasteur and his colleagues, animate Middlemarch.

Certainly we no longer share Eliot’s confidence where social progress is concerned. We read War and Peace and think, “Human folly is inevitable.” If we read a historical novel that relies on the optimism of Marx’s ideas, or for that matter on those of our own American founders, we think, “If they only knew.” But for all that we deplore specific features of technology’s invasion of our lives, most of us retain a confidence that science itself, the knowledge that it brings, is good, and that it represents progress, maybe our only progress forward as a species. A novel about Galileo, or Nightingale, or the conquest of typhoid prompts gratitude, the sense of what we owe to these heroes of science. The fiction writer today who writes about science and its discoverers can rely, just as Eliot did, on readers’ shared sense of wonder and admiration for the work itself.

Charles Darwin’s theories of natural selection and evolution are the heroic presences that hover behind these two new books of historical fiction. In Andrea Barrett’s central story, “The Island,” a young woman scientist is transformed by the experience of reading On the Origin of Species. In Elizabeth Gilbert’s sprawling new novel, The Signature of All Things, a female botanist independently arrives at her own theory, similar to Darwin’s, in the middle of the nineteenth century.

There, it must be said, the similarity between the two books ends. Andrea Barrett is a splendid writer of what, for lack of any better term, we call literary fiction; Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the extremely popular memoir Eat, Pray, Love, is an energetic scribbler. Barrett writes of science and scientists from profound understanding and passion, exploring how scientific reason and human feeling collide and illuminate one another. Gilbert’s novel is another matter.

Hollywood pictures, in the old studio days, often were engineered by committees. Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things, although the product of one person, is a lot like one of those movies—where the script was rewritten a dozen times, they could only get the star by sacrificing half the budget, the director was replaced mid-way, the studio executives recut the whole thing, and at the last minute the director inserted some mismatched black-and-white footage of crowd scenes from the vaults, which had to be hand-colored frame by frame. Sometimes those movies did just fine at the box office, since artistic failure often does not spell financial failure. Here, the exuberance of Gilbert’s voice, and the novel’s specific subjects—plants, the South Seas, a lot of erotic fumbling—may, along with its allusions to important matters of feminism, colonialism, and science, satisfy some readers.

Gilbert’s heroine is Alma Whittaker—unhandsome, clever, and rich—born in 1800, the daughter of Henry Whittaker, who has made his fortune in the rare botanicals trade and in the profitable production of medicinal quinine. The first section of the book is a fast-paced summary of Henry’s career, from son of a gardener in the Botanical Gardens at Kew, to thief of rare plants from that collection, to cabin boy and assistant to the naturalist Joseph Banks on Cook’s voyage to Tahiti. Henry eventually settles down as the wealthy owner of an estate near Philadelphia. All this makes for an awkward beginning, since the account is too brief and attenuated for full fictional exploration, while at the same time it goes on too long to serve as a smooth introduction to what will be the main—indeed in many senses the only—character in the novel, Alma. Moreover it establishes a style most often seen in old-fashioned historical fiction for young adults—an arch “coaxing” of the reader into the past:

Advertisement

But unlike his brothers, Henry had a redeeming attribute. Two of them, to be exact: he was intelligent, and he was interested in trees…. If one wanted to continue living (and Henry did) and if one wanted to ultimately prosper (and Henry did), then anything that could be learned, should be learned. Latin, penmanship, archery, riding, dancing—all of these were out of reach to Henry. But he had trees….

This sickening narrative voice, all-knowing and curiously prissy, dominates the novel. From hundreds of examples, here is just one more, describing the marriage of one of Alma’s friends:

Wifehood, as it turned out, did not suit Mrs. Retta Snow Hawkes. She simply was not crafted for it. Indeed, adulthood itself did not suit her…. Retta was no longer a silly girl who could go driving about the city so freely in her small two-wheeled chaise. She was now the wife and helpmeet of one of Philadelphia’s most respected publishers, and expected to comport herself as such.

Gimmicks (needless repetitions and nudging asides); poor diction and split infinitives; awkward use of nineteenth-century language (“helpmeet,” “comport”)—all irritate throughout. The only thing to keep us engaged is Gilbert’s undeniable talent for story. As we know, many inferior prose stylists are nevertheless capable storytellers, comic-book writers who draw in prose such as J.K. Rowling and Stephen King. Gilbert is not in their league—she’s not that canny at judging pace and surprise—but she does manage to keep the reader engaged, however crudely, in the central question of this novel: Will she or won’t she?

Have sex, that is. Gilbert has created an ugly heroine in Alma. Not plain, like Jane Eyre; ugly. We are told this many times, as if her creator wanted once and for all to disprove that beauty might come from within. Alma has red hair and a big nose. (Gilbert writes: “ginger of hair, florid of skin, small of mouth, wide of brow, abundant of nose.”) So unattractive is Alma that it seems no one will have sex with her, ever, even though she is rich. At a certain point, I gave up disbelieving that Alma was that ugly, and instead started wondering what Gilbert was up to.

Alma is also tall and bulky. Maybe Gilbert wanted to provoke sympathy in women readers who also never feel pretty enough, or thin enough, to be loved. To make her heroine’s condition that much more poignant, Gilbert gives her an adopted sister and a best friend, both of whom are ravishingly beautiful and who snatch up the available men as Alma stoically, miserably watches. Was Gilbert still working out some of the themes from Eat, Pray, Love? That book is the all-time winner in the category of “aspirational self-help” for women who find solace in the struggles of those far wealthier, luckier, and prettier than they are. I can imagine Gilbert wanting to fiddle with the formula—to see what she could do this time with a woman looking for love who was too ugly to find it. But the result has a jeering sort of Joan Rivers meanness to it: Eat, Pray, Just Kill Yourself Already.

This ugly girl winds up book-smart. In addition to her study of her father’s botanical trade and the plants in the greenhouses on the Pennsylvania estate, Alma also has access to a large library, where she learns, among other things, about eighteenth-century pornography from usefully explicit illustrations. Since no man will have her, she puts her knowledge to use in regular masturbation sessions in a closet. Meanwhile, she studies plants, especially mosses, and sighs for love well into her thirties.

Alma does not leave the estate; there are virtually no scenes in the city of Philadelphia, no glimpses of the life in America that was busily roiling along in the first decades of the nineteenth century. A couple of side characters are abolitionists, but this is conveyed in schoolbook-style description of their actions and beliefs, not as part of the plot. Alma is—in all but reading, looking at plants, and masturbating—strangely inert. We are told that she does not socialize in Philadelphia because she’s too ugly to enjoy parties.

Eventually a young man arrives. He is beautiful, poor, and a gifted botanical artist. The Whittakers provide him with a home, and Alma marries him, only to discover that, though he will share her bed, he has no interest in having sex with her. There’s an awful lot of torrid build-up to this let-down. Shamed and enraged, Alma arranges to have him exiled, sent off to run the family’s vanilla plantation in Tahiti. After a few years away he dies; Alma is sent his belongings, which include sketches of a naked Tahitian man. Then the patriarch Henry dies; and then the novel gets really nutty.

Advertisement

Alma decides to go to Tahiti to explore the “mystery” of her husband’s life. At last her total lack of sex appeal pays off for the plot: How ugly is Alma? So ugly that she can, as a unaccompanied woman, travel in safety as a passenger on a whaling ship all the way to the South Seas.

Perhaps because she is writing from personal experience, the author’s narrative voice loses much of its coyness in the travelogue-style scenes in Tahiti. She also cribs, artfully, from history—as happened to Joseph Banks, the islanders steal Alma’s microscope and then return it, piece by piece. Alma also meets, at last, a man who will have sex with her—even though by this point she’s forty-eight, no prettier than she’s ever been, and much the worse for around-the-world wear. Those readers who can assent to Gilbert’s belief that fellating a Tahitian man-god can satisfy Alma’s lifetime of passionate sexual longing may well enjoy the novel’s climactic scene, set in a tidal cave.

The final chapters, after Alma returns home, concern her developing “Theory of Competitive Alteration” (something like natural selection) and her brooding over the problem of intraspecies altruism. None of this is made clear or convincing. Alma’s theorizing, like so many other features of this book, feels tacked on, a notion rather than a real idea.

Inside this big sloppy novel, there is a good short story longing to get out. It concerns a woman botanist in the nineteenth century, and it includes vivid descriptions of her actual work. (There is not one scene in The Signature of All Things that, for instance, depicts Alma teasing the spores off a tendril of moss, or examining its roots. The mosses themselves, though frequently called “green,” are never described in detail. Where are those “pincushion” mosses or fuzzy “fir-mosses” or red-capped “British soldier” lichens, which every casual botanist loves finding in a moss bed?) In this short story, the botanist travels to Tahiti, accompanied by a male assistant or colleague; perhaps she even comes to her own conclusions about evolution. Love and sex might well figure in this story—but they would not overwhelm the narrative

Of course, I am describing a short story Andrea Barrett might write. In her new book, Archangel, Barrett—who has already written a number of superb fictions involving the history of science, among them Ship Fever, The Voyage of the Narwhal, and The Air We Breathe—here offers a group of interconnected stories that take place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, each of which centers around an event or moment in the history of science and technology. “The Investigators” gives us the 1908 flight of an airplane made by Glenn H. Curtiss, as seen through the eyes of a twelve-year-old boy. In 1920, in “The Ether of Space,” astronomers argue about the implications of Einstein’s theory of relativity; in “The Particles,” geneticists returning from a contentious conference in Edinburgh in 1939 are bombed by a German U-boat and forced into even closer quarters on a rescue ship. “The Island” concerns a young woman on a Cape Cod summer study program led by Louis Agassiz in 1873, when he began what later became the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. And “Archangel,” set in northern Russia in 1919, concerns medical science, as an X-ray technician copes with the implications of her work in a war that inexplicably drags on.

“The Investigators” takes one summer in the life of a boy, Constantine Boyd, who has been sent to work on his uncle’s farm in western New York, and examines the layers of his perceptions, experiences, and desires. Here he sees Miss Atkins, a high school science teacher, looking for something in her catfish pond. His uncle, Taggart, is also present.

“Anything?”

“Not today,” Miss Atkins said. She stepped out, pulling the empty trap behind her and revealing bare feet below pants soaked from knee to hem. A little turn of her wrist unfurled a rolled skirt from her waist and concealed her legs. “But I brought fresh bait.” She was slighter than Constantine had first thought and only an inch or two taller than he was.

“Do you think they’re still alive?” Taggart asked.

Pushing into the conversation, wanting for once not to be left in the state of confusion in which he spent part of every day, Constantine said, “These fish—what are they?”

“Cave fish,” Miss Atkins explained, dropping a foul-smelling gobbet into the trap. “Amblyopis spelaeus, native to a cave in Kentucky. They don’t have any eyes.”

The unfussy way that Barrett tells her stories is misleading; what looks so simple is actually the result of exquisite organization, concision, and exactness. How telling is each detail. That the woman is smaller than the boy had thought (he, at twelve, is getting larger but adults are still “big” in his mind); that she is only slightly encumbered by her skirt (women still had to wear skirts in 1908); that she is the authority in the scene (he is learning that there is such a thing as a woman of science); that failure to find the fish today does not mean she won’t tomorrow (science requires patient persistence). All of these pieces of information are laid out so that they can be absorbed by the reader effortlessly. And this is important, because the story being told is enormously complex. In just this one scene, Miss Atkins and his uncle go on to propose numerous theories about the blind fish, speculating about the applications of Darwin’s ideas.

And there are many more complexities. Constantine comes to realize that his uncle’s town is, astonishingly, filled with biologists and agricultural experimenters (graduates of Cornell, mostly), along with inventors of flying machines and motorized bicycles. His uncle and his uncle’s friend Ed live and work the farm together and perhaps also share the affections of a young woman, Beryl. Constantine falls in love with airplanes and half falls in love with a girl. He learns about the daily weighing of milk production from cows, the charting of soils and plant hybrids, the grafting of trees. He likes the tinkering and the measuring more than he likes the theorizing. Crucially, he is having a summer respite from his home in Detroit, where his father is an angry drinker and his mother worries; his taste of this completely different world may change him, and may not; against his wishes, he is sent back at the end.

To get this much richness and depth into a short story without making it feel crammed requires great dexterity. When Constantine reappears, as the grown-up Boyd in the story “Archangel,” his life and the lives of those around him are even more complicated. It is 1919; and although the Great War is officially over, American troops are still under orders to fight the Bolsheviks in Russia, in a terrible, especially pointless series of skirmishes. Boyd, an army ambulance driver who carries the wounded about in a sleigh over the packed snow, arrives in the army base town of Archangel with a frozen corpse and contradictory versions of the events that led to his fellow soldier’s death and his own injuries. This time we see Boyd from the outside, through the eyes of Eudora, an X-ray and fluoroscope technician, assistant to a surgeon whose own war-weariness has made him cynical and unkind. There is an unforgettable ending to this story, in which we remember Boyd’s childhood joy in airplane flight and connect it to his wish, now, to fly free from the horrors of war. Slightly before this ending, Eudora wonders about Boyd’s past:

Where had he lived and what were his parents like, did he have brothers and sisters and a favorite friend, had he left behind one girlfriend or a whole string, a ukulele or a camera or a cherished set of chisels?

We readers who have met him before know only some of the answers. Eudora also ponders the oddness of Boyd having a small bone fragment embedded in his thigh, from another solider who had been blown to bits:

As that was one of the things that could happen, so it did happen, as did everything sooner or later….But everything here was backwards, including her own presence, which had come about by a chain of events so implausible that she omitted most of them when she wrote to her family back home.

It seems as if Barrett here is touching, ever so glancingly, on a matter that must intrigue any fiction writer with an interest in science—that is, chaos theory, which posits that while general trends can be predicted by observation, specific events (since they rely on an almost infinite, and therefore unknowable, number of variables) cannot. Of course the writer of fiction deliberately narrows the variables just enough to make the outcome seem not predictable and boring, but inevitable and right.

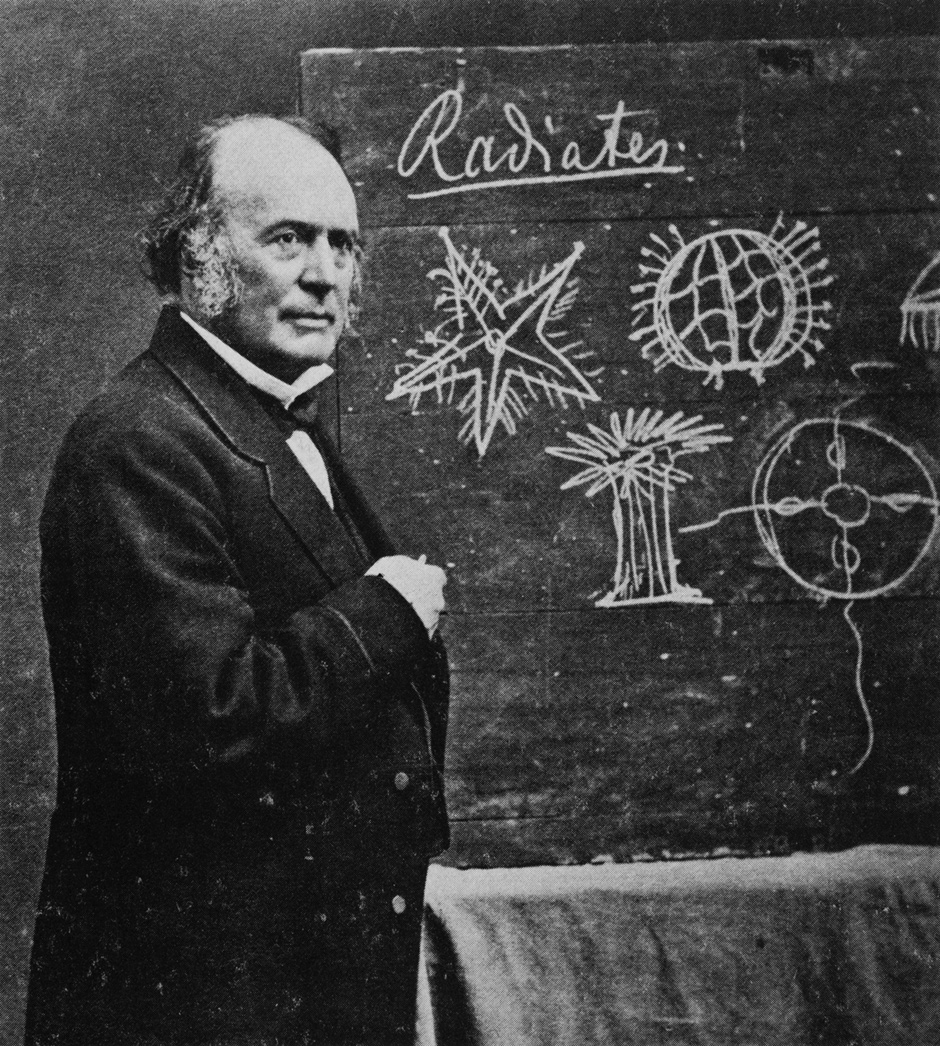

The very best of these remarkable stories is “The Island.” In it, the young Henrietta Atkins (some thirty-five years before “The Investigators” is set) goes to Cape Cod to study under her hero, Louis Agassiz, “the professor.” Like Constantine on his uncle’s farm, Henrietta approaches the strangeness of her surroundings—the great man surrounded by students, haphazard living arrangements, cross-currents of rivalries and alliances—with an often baffled curiosity:

How, Henrietta wondered, did one get given an island? The same way, she supposed, he’d been given a museum, a university department, a staff, a wife who seemed able to read his mind.

Agassiz at that time was vocally disputing with Darwin, maintaining that evolution could not be true because creatures are too complex to have “evolved”—they could only have been made by a divine mind. Henrietta, after she actually read Darwin’s words, feels compelled to disagree.

In one scene the students row out into the harbor to look for jellyfish:

The water had thickened, clotted, raised itself into disconcerting lumps. Suddenly they were floating not on water but on a shoal of jellyfish so thick that the ones nearest the surface were being pushed partially out of the water by those below….

Henrietta slid an empty bowl beneath a clear saucer pulsing like a lung: an Aurelia, thick and heavy at the center, thin and slippery at the edges, over-hanging the bowl all around.

They then encounter a Cyanea—which Henrietta does not know is poisonous. Indirectly punishing her for “going over” to Darwin’s theories, the professor and his wife allow Henrietta to get stung:

The surface felt smooth, surprisingly elastic yet yielding easily to the pressure of her hand. She slipped her left hand from the rounded body into the mass of soft tentacles. Almost instantly her hand began to sting and prickle, and then to burn. With a cry she pulled it out and sat up.

“Oh dear,” the professor’s wife murmured. “I should have warned you….”

Pedantic, apparently unconcerned with his student’s pain, the professor uses the Cyanea as an example to refute Darwin: “How could such a complex mechanism as a lasso cell have developed gradually, in tiny steps, by so-called ‘natural selection’?”

Because Agassiz was such an important and serious scientist, the scene is as sad as it is funny. The resistance to new theories, the pain of change, is one of Barrett’s central themes. Like Henrietta, who eventually recovers, we see creatures in a new way—implicitly—as products of natural selection. While we do not regret the knowledge, we also know that every gain is also a loss, here the loss of the certainty that everything makes sense because it is all from the mind of the creator, arising from a single cause. Moreover, profound uncertainties about love, and about the possibility of happiness, beset the characters in these stories even as they search for clarity in new knowledge and understanding of science. Like Darwin, and Einstein, and all her other heroes, Barrett the storyteller pulls us relentlessly away from false comforts, into the dazzling, often chaotic, world as it really is.