1.

In early June 2011, some three months into the uprising against the regime of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, Syrian government forces began preparing for a large-scale assault on Jisr al-Shughour, a rebellious border town sixty-five miles southwest of Aleppo. The events that led to this operation are a matter of some dispute. Residents of the town said that Assad’s security forces shot and killed an unarmed man during a protest after Friday prayers. At his funeral the next day, thousands of mourners marched to a post office where security forces were gathered.

According to eyewitnesses, government snipers on top of the building began shooting at the crowd, while more troops arrived to back them up. But numerous accounts also describe soldiers defecting and joining with the mourners, a number of whom had brought guns, to attack the regime forces; Syrian state media later claimed that 120 soldiers had been massacred by “armed gangs.”

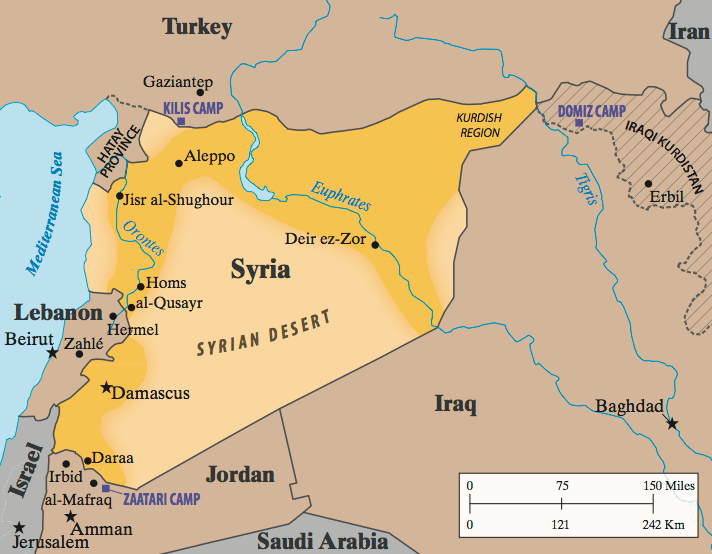

What is certain is that an exceptionally violent confrontation took place. As the regime sent reinforcements to retake control, most of the town’s 44,000 inhabitants and many from the surrounding area fled. “They were burning houses and fields and killing animals. They started shooting. And killed two families,” a woman who called herself Lajia told us when, reporting for a public radio story, we met her in a tiny Turkish village two weeks later. With her six children, then aged six to seventeen, she had escaped from her farm near Jisr al-Shughour across the border to Turkey, where she was staying with relatives. “Villages were increasingly empty from around forty kilometers away,” a United Nations official reported after a fact-finding mission later that month. “Jisr al-Shughour itself was almost deserted.” Like Lajia and her family, much of the population had crossed into Turkey’s Hatay province—the first refugees in a conflict that has since produced more than two million of them.

In more than one way, what happened in Jisr al-Shughour is unusually revealing about the course of Syria’s civil war: it was the first well-documented case of protesters arming themselves and fighting back against Syrian troops. It was also one of the first occasions that large numbers of Syrians were forced to flee to a neighboring country. At the time, the Turkish government had not yet endorsed the Syrian opposition; it had spent the previous decade building economic and political ties with the Assad regime and still hoped for a negotiated solution to the uprising. But Turkey is a Sunni country whose current leadership has Islamist sympathies. Jisr al-Shughour was a Sunni town with a history of Islamist activism and violent repression by Syria’s ruling Baath regime, which is dominated by the Alawite sect. The refugees who left for Turkey soon became the first links in a crucial supply chain for the rebel cause. In July 2011, a few weeks after we met Lajia and other Syrians in the border region of Hatay province, a group of military defectors among them announced the founding of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), dedicated to the armed overthrow of Assad.

Since the summer of 2011, what happened in Jisr al-Shughour has been repeated in villages and towns all over Syria, with far-reaching consequences on almost every side of its 1,400-mile-long perimeter. The country had a population of 22.5 million when the war began; about 10 percent have now left. With nearly a half-million Syrians now in Turkey, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is actively supporting the Syrian opposition and has turned his country into a primary conduit of arms to rebel groups. Along with the FSA, which is favored by the US and its allies, these include other militias, some of them associated with aggressive Islamism. Notably, the Turkish government has not impeded the activity of the al-Nusra Front, an al-Qaeda-linked rebel group that has been designated a terrorist organization by the United States and the UN Security Council.

In Jordan, a far smaller and more fragile country, the arrival of an even greater number of Syrians has raised fears that refugees could bring instability or encourage jihadism among Jordanians themselves. In recent months, the Jordanian government has clamped down on its refugee population while quietly allowing the United States to build up a military presence to protect its border with Syria. In northern Iraq, a rapidly growing population of some 200,000 Syrian Kurds is drawing Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government into a violent new war between Kurds and Islamists in northeastern Syria. Iraq’s Kurdish leaders are meanwhile locked in conflict with Syria’s main Kurdish party over the future of Syrian Kurdistan.

And then there is Lebanon. A tiny, fractious country of about four million people when the Syrian uprising began, the Lebanese Republic has large populations of Sunnis, Shias, and Christians, and especially intricate ties to Syria, which surrounds all of its northern and most of its long eastern borders. According to the government, it has now received well over a million Syrians, most of them within the last twelve months; soon, nearly one in four people in Lebanon will be Syrian. A large majority of the refugees are Sunni Muslims and many Lebanese Sunnis strongly support the Syrian opposition. Yet Hezbollah, the powerful Shia group that controls significant parts of Lebanon, has been fighting in Syria on the side of the Assad regime.

Advertisement

Since early June, when Hezbollah fighters vanquished rebel forces in the Syrian border town of al-Qusayr, there have been a series of bombings and kidnappings targeting Shia areas of Lebanon, including in Beirut itself. “What is happening now is a growing mass fear about the situation,” Makram Malaeb, an official with Lebanon’s Ministry of Social Affairs who coordinates refugee policy, told us in Beirut in late July. “We have to reassure the population that this will not mean the end of Lebanon as we know it.”

About all this, the US and its allies have been largely silent. By contrast, the US response to the alleged chemical weapons attacks near Damascus on August 21 has been swift and dramatic. Even as UN inspectors were visiting a site of the attacks for the first time, the Obama administration began planning a retaliatory strike against the Syrian regime, which was presumed responsible. On September 10, a day after the Russian government gave support to a call to put Syria’s chemical weapons program under international supervision, President Obama said he would allow the UN Security Council a chance to pursue the idea before asking Congress to approve strikes; but he declared it was his “judgment as commander in chief” that the US should if necessary intervene militarily.

In a statement following the attacks, however, the International Crisis Group observed that if the US, with or without its allies, goes ahead with such strikes,

it will have taken such action for reasons largely divorced from the interests of the Syrian people. The administration has cited the need to punish, deter and prevent use of chemical weapons—a defensible goal, though Syrians have suffered from far deadlier mass atrocities during the course of the conflict without this prompting much collective action in their defence.

In fact, well before the August attacks, the daily violence of the war had produced a humanitarian crisis of almost unprecedented scale. One reason many nations have been slow to recognize this—despite the steady accumulation of more than 100,000 fatalities—is that the conflict came relatively late to Syria’s largest cities. A full year into the uprising, which began in March 2011, the United Nations’ refugee agency (UNHCR) had only registered some 30,000 refugees from Syria overall; as late as December 2012, some political leaders in Lebanon, whose borders with Syria are largely uncontrolled and which has for years had large seasonal migrations of Syrian laborers, denied that a refugee problem existed at all.

As fighting reached parts of Aleppo and Damascus in the summer and fall of 2012, however, all predictions were upended. By last September, the number of those fleeing abroad had grown tenfold, to more than 300,000, a figure that doubled again over the following three months. In March of this year, it reached one million. At the beginning of September, more than two million Syrians had left the country, while the average pace had reached five thousand people a day. The UN projects there will be 3.5 million refugees by the end of the year.

After months under siege by both rebels and government forces, some neighborhoods of Aleppo have been abandoned; tens of thousands of Aleppines can now be found in Gaziantep, a city in southern Turkey that locals have begun referring to as “Little Aleppo.” Egypt, a country that had hardly any Syrian refugees a year ago, now has more than 100,000; many are middle-class professionals who view Cairo, for all its upheaval, as preferable to expensive Beirut.

This is to say nothing of the more than four million Syrians who, according to the UN and other aid groups, have been uprooted by the conflict but remain inside Syria; overall, nearly one third of the country’s population have been forced to abandon their homes. Many of those within Syria have taken refuge in schools and mosques in large cities. Tens of thousands of others now occupy makeshift encampments near the border and still hope to leave the country. By April of this year, there were more than a million displaced people in the single northern governorate of Aleppo, many of them subsisting without adequate food, clean water, or medical care, and at continued risk of violence. This summer, in northeastern Syria, Islamist rebel militias have reportedly threatened Kurdish villages with beheadings, kidnappings, and other atrocities, driving tens of thousands toward the border with Iraqi Kurdistan. When a single border crossing opened in August, more than 46,000 Syrians flooded across in ten days, forcing the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq to set a three-thousand-per-day limit.

Advertisement

“We have not seen a refugee outflow escalate at such a frightening rate since the Rwandan genocide almost twenty years ago,” António Guterres, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, told the UN Security Council in July. Analysts with the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU)—the humanitarian arm of the Syrian National Coalition, the opposition’s main governing body—say that still-larger waves of refugees cannot be ruled out. “We are preparing for three contingencies involving the major population centers,” explained Samer Araabi, who runs the ACU’s office in southern Turkey. “A massive movement out of Aleppo—significantly larger than we’ve seen until now; a large-scale migration out of Damascus, if the war came directly to the central parts of the capital; and a movement out of Deir ez-Zor”—a large city in eastern Syria where there has been fierce fighting in recent weeks. “We’re talking hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps all at once.”

2.

Among the many effects of the Syrian war, the collapse of one of the Arab world’s most diverse societies may be the most consequential. The Syrian Arab Republic was long known for its authoritarian government and brutal security apparatus; but it had also been an unusually mixed country for decades. As has been widely reported, Sunni Muslims make up a clear majority (some 74 percent) and Alawites, the sect of the Assad family and many of its supporters, a minority (12 percent). Yet before the war, there were nearly as many Christians as Alawites, as well as the world’s largest population of Druze (700,000) and smaller populations of Ismailis, Sufis, Yezidis, and Shias, among other sects. Though predominantly Arab, Syria also had some 2.5 million Kurds, as many as a million Turkmen, and tens of thousands of Armenians, Assyrians, and other groups.

Owing to its relative stability, Syria had actually been a haven for people escaping persecution elsewhere, from Armenians fleeing the genocide in 1915 and Palestinians chased out of Palestine in 1948—there were some 500,000 Palestinians in Syria in 2011—to both Christian and Muslim Iraqis escaping the recent war in Iraq. In 2006, the Syrian government took in more than 120,000 Lebanese whose homes had been damaged or destroyed in Israel’s war with Hezbollah. When the uprising against the Assad regime began, Syria also had sizable numbers of Somali, Sudanese, and Afghan refugees.

And yet this complicated ethnic and sectarian mosaic made Syria particularly susceptible to large population movements once the uprising turned violent. To a degree, these movements followed basic geography. Punishing attacks by regime forces in the southern governorate of Daraa, where the protests began, drove many of its inhabitants to Jordan, which abuts it in the south. Fighting between rebels and government troops in the northern governorate of Idlib, and—beginning in the summer of 2012—around Aleppo, drove many north into Turkey. And the incessant battles over Homs, in the western part of the country, forced many to seek refuge in nearby Lebanon. (Others remained trapped in the old city of Homs, where they make up one of the most desperate displaced populations in Syria today.)

But at the same time these upheavals led to a new sectarian consciousness. In Turkey and Jordan, a very large majority of the arriving Syrians were Sunnis from areas of Syria contested by the Assad regime, and they were going to Sunni countries that increasingly supported the opposition. (Though Turkey’s Arab Alevi minority has links to Syria’s Alawites, a cause of tension in some Turkish border villages.) Moreover, while not party to the conflict, Syrian Christians have been attacked by Islamist rebels—most recently in the assault on Maaloula, an Aramaic-speaking village north of Damascus, in early September. Many have fled to Christian areas of Lebanon, like Zahlé, a large town in the Beqaa valley where we encountered them; and thousands of Armenian Christians have gone to Armenia. Jordan, meanwhile, fearful of upsetting its precarious demographic balance, has largely denied entry to Syrian Palestinians; more than 90,000 of them have instead taken refuge in Palestinian communities in Lebanon.

In northern Iraq, we met many Syrian Kurds who, though they had been living in mixed cities in western Syria, had nonetheless moved all the way to Syria’s Kurdish-dominated northeast, before crossing the eastern border. “In the beginning, we were all together,” recalled Ahmed, a Kurd and engineering student at the University of Damascus who joined with fellow Arab students in the initial protests. Arrested by the authorities for anti-regime statements he posted on Facebook, he fled to Erbil, in Iraq, where he now watches with dismay the violent war playing out between Kurds and Islamists, who also oppose Assad, in Syria’s Kurdish region.

In some areas, particularly in Lebanon, the Syrian influx is so large that sectarian divisions become blurred. We met non-Palestinian Syrians who had made their way to Shatila, the historic Palestinian refugee camp in South Beirut, despite its reputation for overcrowding and lawlessness. “Lebanon is like Europe, with the [rent] prices,” said Wafa Hamakurdi, a housewife from Aleppo with a family of six. “Shatila was the cheapest thing.” Still more remarkable, many Sunnis have taken refuge in Shia towns controlled by Hezbollah. One local official in Hermel, a Hezbollah town on Lebanon’s Syrian border, said, “We have Syrians living alongside our own families here, and the sons of both are meanwhile killing each other in Syria.”*

The refugee situation has created daunting problems for Hezbollah. The militant Shia organization is terrified that a Sunni-led opposition might defeat its ally, the Assad regime, thus cutting off a vital source of support. Such a loss could also embolden hard-line Lebanese Sunni groups to take on Hezbollah inside Lebanon itself. On the other hand, the more Hezbollah fighters help the Syrian army, the more Sunni refugees will come to Lebanon, perhaps decisively tipping the country’s sectarian balance against the Shias.

And yet in Hermel, as in many other border towns in Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, cross-border ties run deep. One Lebanese farmer, who carried an image of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah on his keychain, had taken in an extended family of eighteen because their own farm in Syria had been destroyed. A critical question facing the entire region is what happens when people like him—many quite poor—can no longer support the newcomers, and public opinion turns against the Syrians.

3.

One of the misconceptions about the Syrian refugee crisis is that it mainly involves people in large camps, above all in Jordan and Turkey. Much has been made in the international press, for example, of Zaatari, the sprawling camp in Jordan operated by UNHCR under Jordanian government supervision, which now houses 120,000 Syrians. Indeed, the social problems that have emerged at Zaatari show the limitations of large refugee facilities and officials say the camp will soon close to new arrivals. But according to UN figures, a full three quarters of the Syrian refugee population throughout the region are surviving on their own in towns and rural areas.

Turkey, which has spent hundreds of millions of dollars setting up twenty-two camps, has more urban refugees than camp dwellers. “Around 300,000 [Syrians] are living outside of the camps, by their own means, and they are extremely in need,” said Suphi Atan, a Turkish Foreign Ministry official. “They create a burden especially on the infrastructure.” In Jordan, refugees in Amman, Irbid, and other cities outnumber camp residents by more than three to one; in Lebanon, owing to political resistance to the idea, there are no camps at all.

This has made it particularly difficult for international aid organizations to respond. “You look around and you wonder, where are the refugees?” said Niamh Murnaghan, director of the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Lebanon office in Beirut. “It’s a hidden crisis, that’s the most difficult thing.” In Gaziantep, Turkey, we met Ahmet Nassan, an internist from Aleppo who, lacking Turkish certification, cannot practice medicine; he now supports himself working as a translator at a private hospital. In the same city, sixty more Syrian doctors, who are Turkish-trained, can’t find work. In Beirut we discovered a Syrian man and his young daughter living in an abandoned building across the street from the UN refugee agency’s Lebanon office. His wife was killed by regime shelling in his Damascus neighborhood, and he had escaped in his flip flops, with the clothes he was wearing.

Meanwhile the hidden population continues to grow. Khaled Ghanen, who runs an Islamic charity in al-Mafraq, Jordan, recalled that at the beginning of Ramadan in August 2011, his charity had helped sixteen families. By the end of that month, there were forty. By the end of the year, there were five hundred families; a year later, he estimates 15,000 families. Now he is seeing fifty new families a day. Until the middle of last year, the charity was able to offer rent money and employment help. “But now, there is no housing and no jobs to find,” he said. “The whole kingdom [of Jordan] is filled with Syrians. Our city is not receiving them, though. She is throwing them away.”

For those who end up in a camp, conditions vary widely. At Kilis, on Turkey’s southern border near Aleppo, we found some 13,000 Syrians living in container houses with satellite dishes and air conditioning, with access to a newly built school, health clinic, and mosque; but Turkish officials told us that camps like Kilis are now full. By contrast, in northern Iraq, a poorly planned camp called Domiz has been allowed to grow into a teeming shantytown for some 70,000 Syrians. It is difficult to imagine how its primitive canvas tents will survive the harsh winter. At Jordan’s Zaatari camp, residents are forbidden from leaving without a special permit (for which there is now a thriving black market trade)—part of an effort by the Jordanian government to control the spread of jihadism. Yet in Turkey’s Hatay province, a special facility for Syrian military defectors has been used as a command center for the FSA, and rebel fighters commute back and forth from the camps to the front lines.

But housing—whether in tents or containers or abandoned buildings—may not be the most pressing issue facing Syrian exiles. One of the defining facts of the Syrian crisis is the startling number of children who have become refugees—a number that reached one million in August. Before the conflict began, oil revenues were sufficient for the Assad regime to provide free education and health care to most Syrians. Between 1995 and 2011, the population expanded by nearly nine million people, or 65 percent, leading to a society in which more than four out of every ten people are under the age of fifteen. Many Syrian refugee families we met had six or more children; some women had given birth after fleeing the country. “The population growth rate is tremendous,” said Malaeb, the Lebanese official. Even if Lebanon stopped taking in Syrians now, he said, “there are going to be two million Syrians in three years.”

Already, the number of school-age Syrian children in Lebanon is scheduled to surpass the entire population of school-age Lebanese children by the end of the year. In Gaziantep, Turkey, there are so many Syrian families that a Syrian school has been started, with a Syrian curriculum, staffed entirely by volunteers. But according to UNICEF, as the new school year begins, nearly two thirds of Syrian children in Jordan remain out of school. Early marriage is common for refugee girls; in Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq, we saw young Syrian children selling things like tissues and soap on the streets.

Everywhere, there is fear of spreading disease. There has been an alarming rise in the incidence of leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease common in the Aleppo region that had largely been controlled: since the conflict began, doctors in Syria and Turkey have diagnosed 100,000 cases of it. In Lebanon, diseases that had been nearly eradicated, like tuberculosis and measles, have now reemerged in refugee populations; the country’s overwhelmed hospitals are increasingly unable to meet the demand. And while Syrian doctors find themselves unemployed in Turkey and elsewhere, Syria itself has suffered an acute shortage, with the number of doctors still working in the country having dwindled from 30,000 to 5,000, according to one recent estimate.

4.

Over the last few months, as the Syrian refugee population has surpassed even the extraordinary numbers produced by the Iraq war seven years ago, the world has finally begun to notice. In early June, the United Nations launched a $5.2 billion aid appeal for Syria and neighboring countries affected by the war—until now its largest such appeal ever. (By September 2, some $1.5 billion had been raised.) In July, US Secretary of State John Kerry visited Jordan’s Zaatari camp, where Syrians staying there accused him of “nonaction.” Kerry responded that the US was considering further steps, and on August 7, President Barack Obama announced that the US was offering another $195 million in humanitarian aid to help Syrians.

Even if the UN’s daunting fund- raising goals can be met—and even if the vital contributions by NGOs, wealthy donors in the region, and individual Syrians themselves can be increased further—many of those in need will be out of reach. Since this spring, the Jordanian government has significantly limited the flow of Syrians into its territory while allowing the US to step up military aid. Jordan’s overriding concern “is very clearly the refugee issue,” General Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told The New York Times in August. Meanwhile, many refugees described being prevented from crossing from Syria into Turkey and Jordan, with some resorting to bribes and others forced to seek shelter elsewhere. The autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq closed its border to Syria from late May to mid-August, while Baghdad has deployed troops to guard Iraq’s long borders with Syria in Anbar and Nineveh provinces. (The Shia-led Iraqi government has accused Sunni “terrorist” groups of infiltrating the country and smuggling in weapons from Syria.) And Lebanese officials say they too are considering measures to slow down the number of Syrians crossing at the one border that has remained completely open throughout the conflict.

As a result, precisely when Syrians have become most vulnerable they may have no way of getting out or getting help. Despite the heroic efforts of its staff, the Syrian Red Crescent, which nominally operates under the authority of Damascus, is often unable to reach rebel-held areas or major conflict zones. Already in March of this year, the UN declared that “civilians have almost no safe place to go” in Syria. In the summer of 2012, thousands of displaced Syrians took shelter in Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp south of Damascus; but in December of that year, Yarmouk itself was bombed by Syrian planes, compelling most of them to flee a second time. For much of the war, Syria’s northeast has been relatively calm, becoming a destination for tens of thousands of displaced families from other parts of the country; but since vicious fighting erupted there this summer, 250,000 people have again been forced to move.

One of the unambiguous lessons of this refugee crisis is that, at every stage, violent confrontations between rebels and the army, or between rebels and pro-regime militias, or even among different rebel groups, have made it worse. Addressing the problem will require not just huge amounts of humanitarian aid but also a concerted international effort to limit the conflict’s spread.

Action, however, may bring its own costs. The international sanctions now in force against Syria, for example, have hurt those already suffering from the conflict by helping devalue the Syrian currency and further disrupting aid delivery. According to a study earlier this year by the Danish Institute for International Studies, Syria’s poor are now

faced with inflation, higher food and fuel prices, import restrictions, and higher unemployment…. Import restrictions and trade disruptions have forced many local vendors who provided supplies to aid agencies to close down.

More promising may be efforts to adapt military strategy to civilian need. In a recent report, Anthony Cordesman, the American military analyst, called for a “broad international effort to support Syrian refugees inside areas in Syria where moderate rebel factions and NGOs can operate.” He suggested this could be done through a “civil-military” plan that would give as much emphasis to programs like the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which is currently helping organize food distribution in parts of Syria, as it does to military support for the rebels.

A larger irony of course is that, while closing their borders to Syrian civilians trying to escape, Syria’s neighbors are becoming more and more drawn into the conflict themselves. In contrast to refugees, fighters for both sides now travel freely in and out of Lebanon, Turkey, and—in spite of official restrictions—Jordan and Iraq. In northern Iraq, the Kurdistan Regional Government has been building a “Syrian Peshmerga,” a militia of several thousand Iraqi-trained Syrian Kurds, to be deployed in the Kurdish region of Syria.

As the violence continues, the international community—and Syrians themselves—have been increasingly divided about the Obama administration’s proposed strikes on Damascus. A number of refugees asked us why the US wasn’t doing more; many clamored for a no-fly zone. Others argued it was too late now for the US to enter a conflict that had long since been taken over by violent militias, many financed by foreign powers such as Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. On September 9, Navi Pillay, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, said that the

appalling situation cries out for international action, yet a military response or the continued supply of arms risk igniting a regional conflagration, possibly resulting in many more deaths and even more widespread suffering.

Largely ignored in this debate, however, has been the crucial question of whether—and when—the millions of Syrians who have already fled will be able to return to their homes. The prospect of a negotiated cease-fire, followed by the establishment of a transitional government or administration, has been suggested by some international officials, and if successful, might allow for the safe return of Syrians to at least some parts of the country. But many we talked to expressed doubts that the Syria they knew could ever be rebuilt.

—September 12, 2013

This Issue

October 10, 2013

The Two Faces of US Education

A Magus of the North

-

*

See Hugh Eakin, “Hezbollah’s Refugee Problem,” NYRblog, August 12, 2013. ↩