A cursory glance at the title of Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger’s first-person saga suggests a kinship with the BBC One television series Play It Again that launched in 2007 and documents the attempts of celebrities to learn a musical instrument. Just over halfway through his eventful and sometimes harrowing sixteen-month account of tackling Chopin’s Ballade in G Minor, Op. 23, a monument of the piano repertoire, Rusbridger serves up a more intriguing rationale:

Should I ever make a book out of my endeavour with the Ballade, I resolve, I’ve at least got the title: Play It Again. It has two associations apart from the possibility that I might be sitting in front of an old upright piano in Casablanca this time tomorrow night: returning to the piano as an adult, and the fact that it’s only by endless repetition that any progress is made. The journalist in me also likes the fact that it’s a misquote. Bogart never said it.

In a modestly viewed YouTube post by The Guardian in January 2013, Rusbridger amplifies:

I thought of the title in Libya. I’d gone on the last flight into Libya before the no-fly zone to try and rescue a Guardian correspondent who had been kidnapped. And in Libya I was in this deserted hotel playing this piano in the hotel that nobody wanted to stay in. And it looked as though the only way we would get out was via Casablanca. And there’s something about getting it wrong. Humphrey Bogart never said it. And in the middle of the Leveson Inquiry [the public investigation growing out of the News International phone-hacking scandal] it kind of appealed to me.

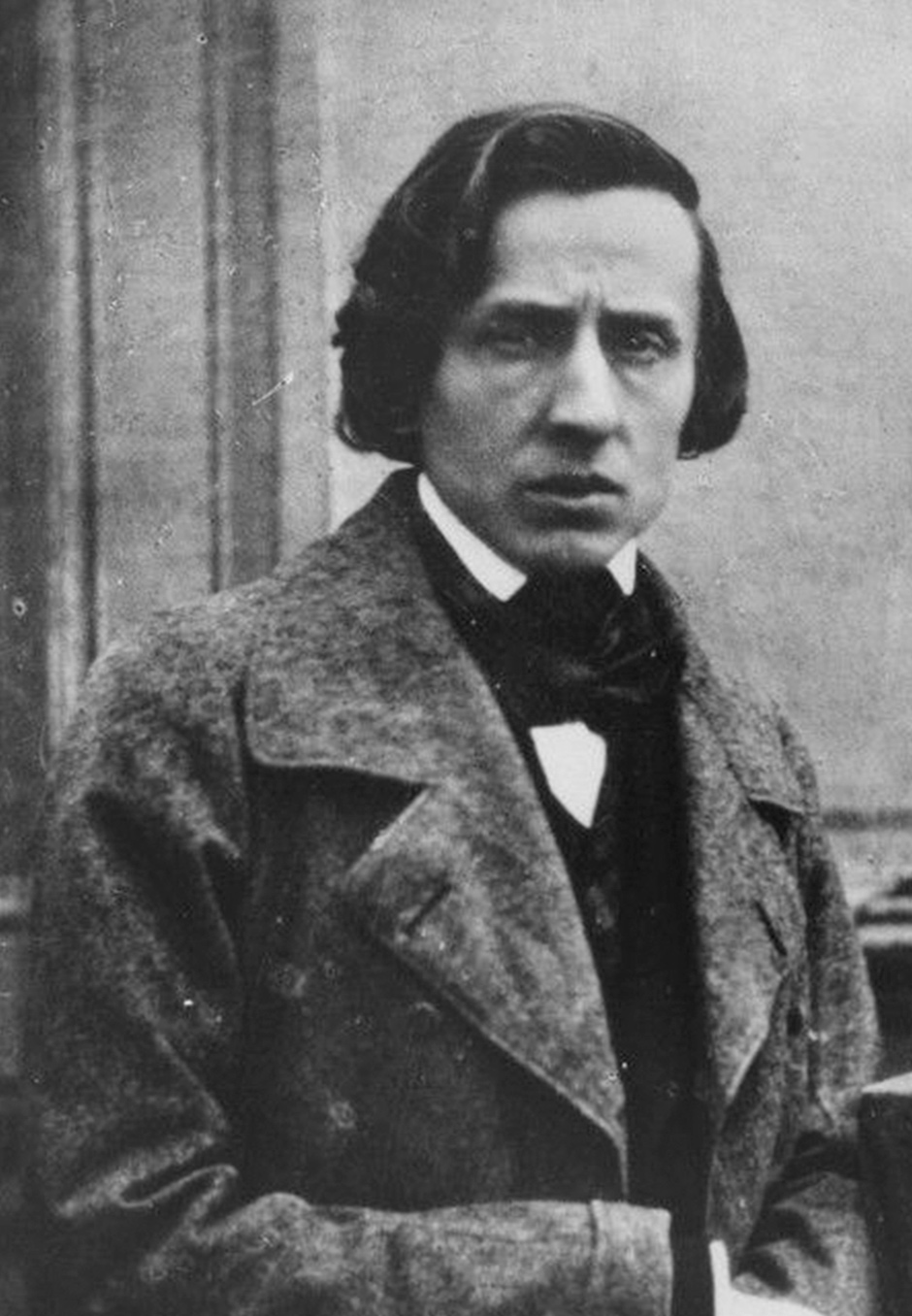

Indeed, in the 1942 film Rick simply tells his pianist: “Play it, Sam.” Woody Allen’s 1972 movie, Play It Again, Sam, obliterated any collective memory of the original line. But in Rusbridger we have a writer who in the deepest recesses of his mind delights in a conviction that everything is at some level connected—in this case Chopin to high-stakes journalism and power politics. What sets this particular odyssey apart is not just a protagonist who might seem to have no discretionary time but the improbable and daunting choice of “the Impossible”: mastering (or at least taking on seriously) Frédéric Chopin’s ballade, a ten-minute cornerstone of the Romantic repertoire both loved and feared by pianists, composed in 1835–1836 when Chopin was in his mid-twenties.

During Chopin’s lifetime the piano rose to talismanic status in Europe (and eventually America), a position it maintained until the advent of the phonograph. Something talismanic still remains about playing the piano. Show up at a reception and tell the first person who asks after your profession that you are a pianist, and a spark inevitably flickers across their eyes, perhaps punctuated by “Oh wow!” This is frequently followed by a confession that at one time the questioner also took lessons, climaxing in genuine if momentary regret at letting them slide.

Today playing the piano is an implausible mix of ebb tide and tsunami. Ebb applies to the perhaps two dozen touring pianists worldwide who still earn all of their income from public performances. Tsunami refers to the purportedly six million Chinese alone who are currently studying piano in conservatories and institutions of higher education. Each year American schools of music crank out hundreds of graduates at all levels who major in piano. A job opening in piano at even a mid-level university in a nonprime location can easily attract three hundred applications.

Recitals for solo piano have become increasingly uncommon. Created single-handedly by Franz Liszt in the 1840s, they reached their peak of frequency and prestige shortly before World War I and have been slowly dwindling ever since. The most prestigious venues from Los Angeles to Moscow once offered dozens of solo piano recitals annually. Today, although smaller venues have taken up some of the slack, the kinds of “celebrity series” that almost biweekly used to include an Artur Schnabel, Alfred Cortot, Vladimir Horowitz, Rudolf Serkin, or Sviatoslav Richter have shrunk to less than half that number. In the 2013–2014 season, New York’s Carnegie Hall offers ten piano recitals in its main-stage Keyboard Virtuosos Series; along with the nine piano recitals for that same period at London’s South Bank Centre, New York and London maintain the biggest programs in this niche market.

Alan Rusbridger, an unapologetic and disarming advocate of music by a composer who died 165 years ago and wrote for an instrument whose design has scarcely changed since the 1870s, should give pause to all who profess any connection to this tradition. In a classical music industry dominated by cries of doom, he cheerfully dives in, and across some four hundred pages of Play It Again, the pursuit of Chopin holds its own with WikiLeaks and the News of the World phone-hacking scandal.

Advertisement

Rusbridger is not alone in his pursuit of ambitious music. A recent and much-quoted (especially by musicians) Opinion piece in The New York Times lists more than a dozen public figures who are or were enthusiastic musical amateurs: Condoleezza Rice, Alan Greenspan, hedge fund billionaire Bruce Kovner, Paul Allen of Microsoft, Woody Allen, Steven Spielberg, Paula Zahn, NBC’s Chuck Todd and Andrea Mitchell, Google cofounder Larry Page, venture capitalist Roger McNamee, advertising executive Steve Hayden (creator of the Apple “1984” Super Bowl ad), and former World Bank president James D. Wolfensohn.

Another piece in the Times describes Bostonians and New Yorkers who took up an instrument (from cello to electric guitar) in their sixties and even seventies. All of these musical amateurs offer a litany of reasons for their engagement: learning to problem-solve, to collaborate, to listen, to weave together disparate ideas, to focus simultaneously on the present and the future, to develop pattern recognition, to appreciate the quest for perfection, to understand the requirements for improvement, to trust one’s own creativity, and simply as an emotional outlet from the stresses of life.

Yet no one—including a sizable scholarly literature on pianos and piano music—has delved into the process so enticingly as Rusbridger. This remains true in spite of a limp diary format organized abstractly as Part One to Part Eight, framed by an introduction and epilogue. The parts themselves provide little structural mooring, ranging from a few dozen to almost a hundred pages, with boundaries determined by anything from the end of a vacation to the end of an interchange on information theory applied to music-making.

Rusbridger’s nineteen-year editorship of The Guardian has been widely admired for its fair- and sometimes tough-minded progressive journalism. Born in former Rhodesia but returning to England with his family at age five, he had access to the kinds of privilege—prep schools, Cambridge University—that produces members of Parliament and business tycoons. Rusbridger worked up through the ranks the old-fashioned way, beginning as an intern at the Cambridge Evening News before joining The Guardian in 1979 in a series of increasingly responsible and influential positions.

Rusbridger confesses to having “mucked around on the piano” from the age of eight, replete with a mother’s ritual exhortations to practice more. Instead he became a competent clarinetist, playing in local amateur orchestras. Between his teens and his mid-forties he was no more than a keyboard dabbler. His path to the passionate pursuit of the piano began, as is so often the case, with an epiphany. At an annual week-long gathering of amateur pianists in central France, an unassuming fellow amateur (Gary, no surname) ambushes Rusbridger and his fellow participants with a stunningly assured performance of the Chopin G-minor Ballade. Although he did not know it at the time, the astounded author was hooked. Had he instead heard Maurizio Pollini dispatch the Ballade once again at a live concert in Wigmore Hall, the magical moment would never have taken place. But if Gary, a former cab driver and pub operator, could pull it off, why couldn’t Rusbridger?

Westerners have long indulged in a voyeuristic, almost fetishlike fascination with the notion of “An Amateur Against the Impossible,” Rusbridger’s subtitle. The most gung-ho and recidivist amateur was surely George Plimpton, whose “participatory journalism” led him on a series that began with pitching batting practice to the New York Yankees before a post-season exhibition game. He went on to spar for several rounds with the boxer Archie Moore and attend training camps of both the Detroit Lions and the Baltimore Colts in order to appear in a few plays. Among much else, he played the triangle under Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic.

Serious portraits are rarer. Penn and Teller’s well-received 2013 documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, recounts the five-year quest of graphic designer Tim Jenison to reproduce the colors and light patterns of the seventeenth- century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. Jenison is at great pains to explain that he is “not a painter.”

Amateurs are sometimes ridiculed (fear of which grips Rusbridger periodically), especially when ego outstrips ability. In the operatic world most are exposed sooner or later to the delusional delights of flapper-era socialite Florence Foster Jenkins, who failed to discern any difference between her caterwaulings and the great sopranos at the Met.

This inevitably raises the question: What is an amateur? The orchestra that premiered Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony consisted largely of dilettanti, a contemporary term that referred to people whose profession was in a field other than music—in other words, amateurs. In Rusbridger’s own Britain, the hordes of brass bands originally founded to burnish the reputations of smokestack companies are still peopled by as many amateurs as professionals, and the amateur ensembles often walk away with the prizes at the most prestigious competitions.

Advertisement

Over the last decade the concept of the “amateur professional” (referred to interchangeably as Am-Pro or Pro-Am) has taken hold. These are persons best described as consumers rather than producers. They pursue their hobbies through deadly serious passion rather than corporate strategizing (mountain bikes and rap both fit this profile).

Locating Rusbridger along this amateur continuum, then, is tricky. His original claim to amateur status rested, as he quickly concedes, on neglect. By his own admission a good “sight reader” (playing on sight music one has not seen before—something many accomplished pianists are poor at) who never severed altogether the habit of playing with other amateurs, he became just good enough to know how much better the pros were.

His biggest obstacle? No time to practice. “The very best I can hope for,” he confesses, “is fifteen to twenty minutes a day”—a meek goal that world events only compromise further. Even those who have never touched a piano key recognize the popular image of hunched-over pianists turning in ten- to twelve-hour days. Rusbridger’s plan sounds tantamount to a lover of verse allotting twenty minutes a day to memorizing Book I of The Iliad. Laments from both the author and others over the lack of practice time recur like a refrain. An incredulous Murray Perahia says: “You need two hours a day for anything to stick. Twenty minutes is not enough.”

To assess the chances for success on his terms, Rusbridger consults with scientists. Fearful of his ability to memorize, he learns from neuropsychiatrist Ray Dolan about explicit and implicit memory. Explicit memory is flexible: you remember where a bridge is but you can use that information in various settings. Playing the piano belongs to a subcategory of implicit, and largely inflexible, memory known as “procedural memory”—you reel off the music as a series of prepared sequences. Most encouraging for the fifty-something Rusbridger is that, although the brain is most flexible at a young age, it can “learn new tricks”—in scientific terms, sprout new dendrites, whose connections can actually change the shape and density of the cerebral cortex—at any age.

Neuroscientist Lauren Stewart, herself an amateur violinist, confirms that rather than your brain determining what special skills you may acquire, it actually adapts to the skills you learn. The part of the brain controlling the very busy left hand of violinists, for example, eventually occupies a larger portion of the somatosensory cortex than the portion responsible for the less complex right (or bow) hand. These revelations engender a kind of giddiness in Rusbridger.

His diary, then, is a conceit, a stream-of-consciousness platform for exploring the challenges of remaining human in a world that moves at the speed of Twitter. He is at root a journalist, and the best of them open up complex areas of inquiry to nonspecialists. Some may find his brain forays to be pop science that ignores other equally important issues. Why, for example, are a precious few born with the prodigious natural aptitude for a highly specialized skill, whether the chess player Magnus Carlsen vanquishing in serial fashion ten professional opponents with his back disdainfully to them, or Mozart dashing off the last movement of a piano concerto a few hours before its premiere? One imagines Rusbridger responding that genius is a concept in Western culture that needs no defenders, whereas middle-aged growth is very much in need of a sales force.

To aid and abet growth, Rusbridger uses his connections to obtain interviews with A-list pianists. Along with Perahia he confers with Emanuel Ax, Stephen Hough, Alfred Brendel, and the redoubtable Charles Rosen, so familiar to readers of these pages. You can sample their thoughts as annotations to the facsimile of the battle-scarred score that Rusbridger appends to the end of his journey. What jumps out is the differences between what they say and the tone of most scholarly writing on the subject. Ax likens the first seven bars of the ballade to the opening of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Perahia hears the somber theme that follows as “the sadness about losing, about Poland being under the grip of three powers.” Hough experiences the soulful second theme as “some sort of unobtainable happiness happening somewhere else, perhaps. I don’t think it’s Chopin experiencing that.” The well-versed Rosen notes how the ballade was related to Italian opera—the opening bars resembling bel canto; the distinct ending recalling a cabaletta, the quick final section of an aria.

About the same opening seven bars compared by Ax to Coleridge’s famous poem, Jim Samson—the most prolific British writer on Chopin and a recipient of the Order of Merit from the Polish Ministry of Culture for his contribution to Chopin scholarship—writes:

The introduction composes out a “Neapolitan 6th” harmony in the manner of a recitative. Chopin had a weakness for Neapolitan harmony, and here it shapes yet another tonally elliptical opening of a kind which is the rule rather than the exception in his major works.

This is doubtless why Samson appears only in the “Further Reading” rather than within Rusbridger’s narrative. The two quotes highlight in overly simplistic yet dramatic fashion the cleft between scholars—who write for a small, specialized clientele—and performers—who strive to connect with their listeners in a visceral fashion.

Based at Rusbridger’s alma mater of Cambridge, the Research Centre for Musical Performance as Creative Practice is a joint venture of every major participant in British academic music, including the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, King’s College London, the Royal College of Music, and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Its director, John Rink, has published widely on Chopin. His more sober and quantitative approach makes no appearance in Play It Again. Nor, regrettably, do Chopin scholars such as Jeffrey Kallberg, whose work speaks powerfully across conventional disciplinary boundaries.

Rusbridger embraces the performer approach. Among the most remarkable entries in Play It Again is an early one, for August 8, 2010; it escorts the reader almost bar-by-bar through the entire ballade. Snobs will find it too easy to spot elementary errors (bar 7 is not a Neapolitan sixth; that’s the harmony that opens the piece, etc.). But despite its array of a dozen musical examples, this seat-of-the-pants account will hold even the most uninitiated reader under its spell. His commentary is always linked to specific musical events. One passage is “never quite as tender, nor as sweet, nor grandiloquent, nor charming as it seems at first.” Another finds the “RH [right hand]…flying up and down the keyboard in trapeze-like leaps…. Something diabolic is happening.” Among the “horrendous technical challenges” is a passage whose notes look like “squashed flies on a page.”

Such entries recall a time when ascribing qualities to a piece of music raised no eyebrows. In 1789 Daniel Gottlob Türk could write without affectation in his Klavierschule:

In pieces whose character is violence, anger, courage, fury and the like, one can accelerate in the strongest passages…. In extraordinarily delicate, languishing, sad passages, where the expression presses to a single climax, the effect can be tremendously strengthened by a gradual slowing….

Although developments in musical scholarship over the last three decades can hardly be summarized here, an important trend has been slowly allowing words that characterize a piece of music beyond strictly musical descriptions back into the conversation.

Rusbridger’s direct sources of inspiration are more prosaic. Before his adventure attains a full head of steam we encounter the Victorian Arnold Bennett, whose How to Live on 24 Hours a Day (1910) advises the salaryman to “get up earlier in the morning…. Rise an hour, an hour and a half, or even two hours earlier.” This is easy for the considerably less pressured Bennett to say, yet rising a half-hour earlier is exactly what Rusbridger sets out to do.

Rusbridger’s greatest affection is reserved for a short book published in the 1940s, Charles Cooke’s Playing the Piano for Pleasure, recently reissued and edited by the distinguished art critic Michael Kimmelman (himself a high-level amateur pianist). For Cooke the secret is preserving your amateur status: “Remember, you are more fortunate in your playing than most professionals are in theirs. For you there is no grim grind of practising; no exhausting burden of responsibility; no fierce competition….”

It is hard to imagine that the entries in Play It Again were written just before bed on the dates to which they are attached. Conversations must have been recorded (there are too many lengthy direct quotes), reviewed, and edited in a rigorous fashion. Yet Rusbridger has mastered omnivorous high-end chattiness to a degree that makes readers feel they are hearing this unlikely tale over a cup of tea or a good Scotch. We come to care about the progress on his music room at Fish Cottage as much as we do about his negotiations with Julian Assange. Many a page emits the warm glow of Dickens, here as a Tale of Two Brain Hemispheres that complete rather than compete with each other.

Books like Play It Again run the ever-present risk of narcissistic overtones. But Rusbridger describes his jousts with those in power in a straightforward fashion that calls relatively little attention to himself. About his own musical talents he takes gentle self-deprecation to a new level.

It would be nice if the index had included topics and concepts (for which the searchable Kindle edition recommends itself) along with the litany of names and institutions. The brief “Further Reading” looks like a messy afterthought. The YouTube video containing Rusbridger’s rendering of the last, quite playable eight bars of the ballade suggests that this performance before friends was recorded in its entirety. We never hear any of the unplayable “bits” about which he writes so zealously. Detractors will argue this is because they include mishaps. That would miss the point. “I’ve learned my mother was right…right that music ability is both a social ice-breaker and the forger of deep and lasting friendships,” Rusbridger concludes. While on the face of it a platitude, it is the author’s journey rather than his destination that we remember. In the end he is selling not triumph—leave that pointless pursuit to the politicians—but a powerful entreaty, merging science and the humanities, to engage before rigor mortis comes calling.