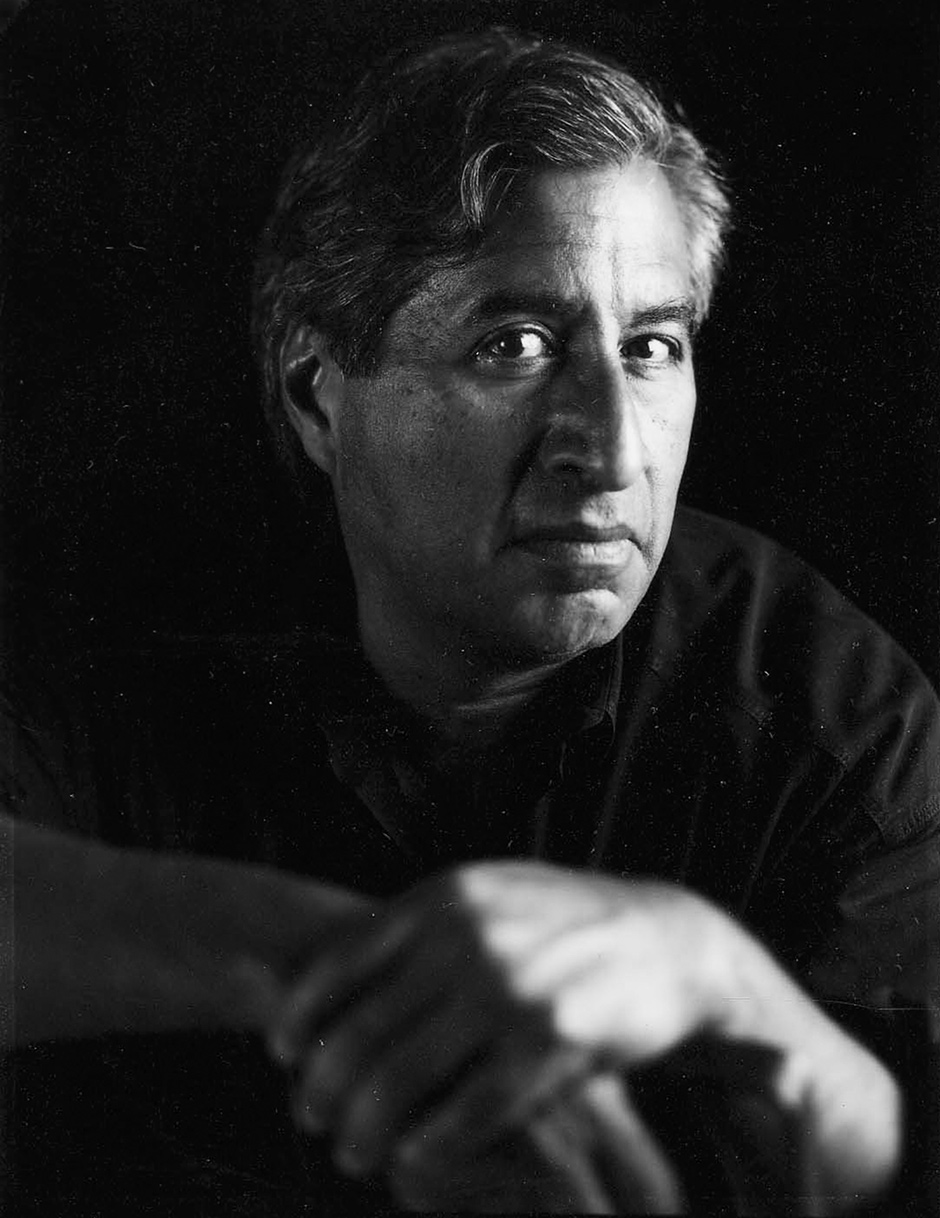

It’s exhilarating to come upon a writer whose moves and positions one can’t anticipate. Writing of Las Vegas in his latest book, Richard Rodriguez dilates a little on Noël Coward’s stay in the Nevada desert (the British playwright found the gangsters there “urbane and charming”); he tells us about the Spanish teenager who in 1829 was perhaps the first European traveler to lay eyes on the valley and gave it its current name (which means “the Meadows”). He circles for a while, as many writers might, around Ozymandias and discovers an eighty-four-foot-long Maya Lin sculpture in the lobby of the Aria Hotel. True to his generally melancholy and paradoxical cast of mind, he notes that Vegas is a city that lives off the sorrows of others, less a vindication of the American belief that everyone can become a millionaire than a monumental reminder that the majority of gamblers are failures.

Yet before any of that, he begins his chapter by writing of a gay friend who’s dying in a hospice in the desert outside Las Vegas. And even as he keeps reflecting on his suite at the Bellagio, he also keeps returning to his visits to his friend. The alert reader begins to register how often hospital wards haunt his book; Rodriguez, now seventy, is clearly thinking in his fourth book about what any of us leave behind. And when he discloses that his friend dies, as it happens, on Easter Sunday—the bumper sticker on a van in front of the author’s car says (in Spanish), “ONLY GOD KNOWS IF YOU WILL RETURN”—you may remember that the chapter before this one (which is called “The True Cross”) was entitled “Jerusalem and the Desert.”

Bringing disparate worlds together—seeing Las Vegas in the light of Jerusalem, Jerusalem in the light of Las Vegas, so as to catch each at an unexpected angle—is part of what makes Rodriguez an original. At every turn, he mixes registers, frames of allusion, references to his Mexican family with references to the privileged cosmopolitan circles his writing has admitted him to. As a lonely student in London, he tells us here, his copies of Milton sat next to those of the British society magazine Harpers & Queen.

An anti-ideologue of sorts, he writes to keep everything in play—he has a clear, droll fascination with the tinsel of the streets, even as he cherishes his Catholic remove from the world—and to keep the reader questioning everything, most especially our too simple ideas about America and identity. His tone is that of the mournful outsider at the feast—Antonio in The Merchant of Venice, say—who heads off alone for his contemplations while happy lovers pair off and go to the nuptial feast.

This contrarian bent was announced in his very first book, Hunger of Memory (1982), in which the Mexican-American scholarship boy argued against the affirmative action policies that had perhaps helped him to become a writer, and claimed that bilingualism was essential precisely because it allowed him to lead contradictory lives, to be a man of secrets and inconsistencies. Yet the subtitle of that work—“The Education of Richard Rodriguez”—also suggested that Rodriguez was no more a man of the right than of the left: the defining new American, he was saying, was a kid speaking Spanish, from an immigrant home in Sacramento, with a name that Henry Adams would barely have been able to pronounce.

In the years since, as a regular contributor to Op-Ed pages and a longtime essayist for PBS, Rodriguez has constantly delighted in rubbing his incompatibilities together, as you might say, so as to succeed in offending almost everyone: he’s a gay Catholic who’s too diffident for those who share the adjective and too outspoken for those who share the noun. A God-haunted liberal, perhaps, who sits among the New Age wooziness and born-again affirmations of San Francisco and writes of death.

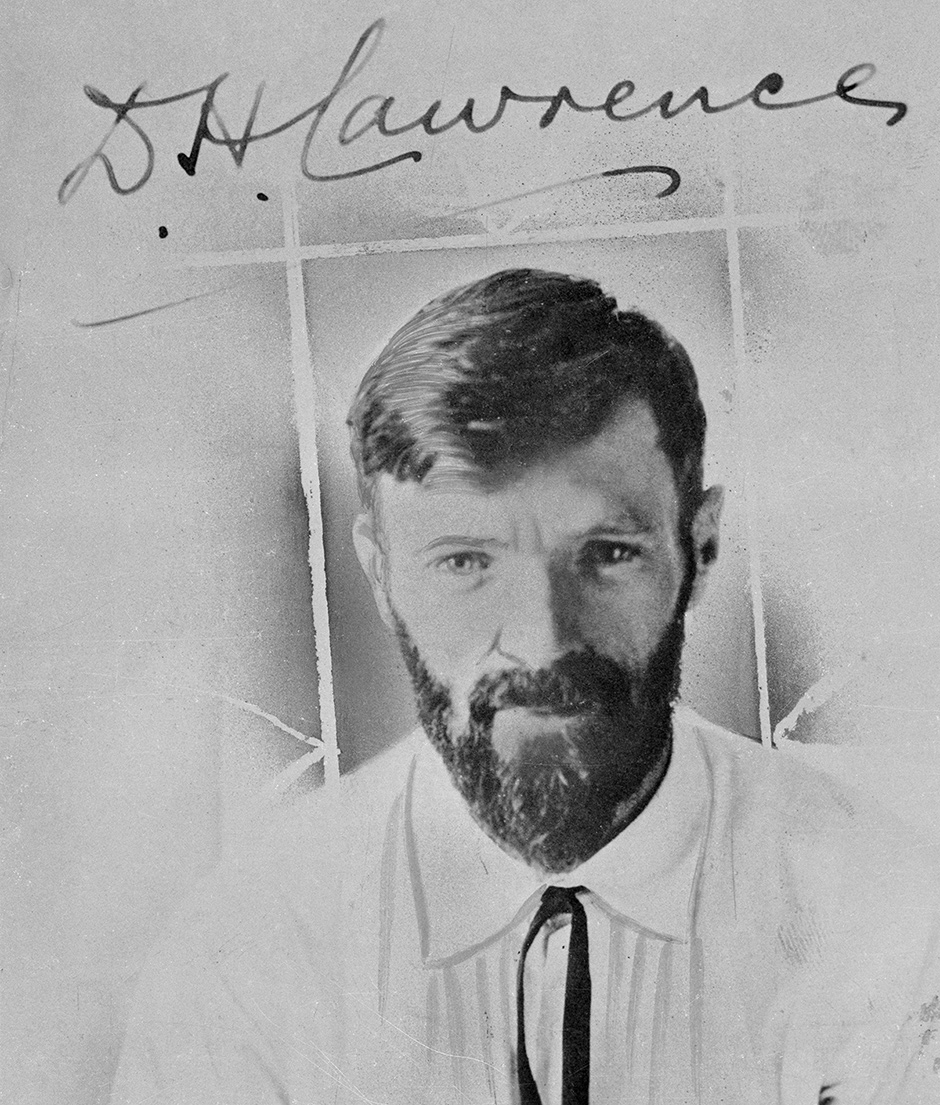

His prose is equally defiant of all orthodoxies: Rodriguez arrests and sometimes unsettles by writing of our most public issues in a deeply private voice, which again and again, unexpectedly, draws upon fragments from his own experience so as to place topical issues on a much wider, even allegorical canvas. Near the beginning of his new book, discussing Catholicism and Islam, for example, he tells us how he grew up shuttling between two temples in his hometown—the Sacred Heart Catholic Church and the Alhambra movie house. Earnest self-erasure, you could say, and ornamental self-expression. Each of his four books is essentially a memoir of ideas. And though you could liken his procedure—a lyrical torrent of assertions—to that of Octavio Paz, say, Rodriguez would more likely associate it with that of the anti-Mexican, anti-American D.H. Lawrence, or Virginia Woolf.

Advertisement

Look, for example, at his celebrated essay “Late Victorians,” which sits at the heart of his second book, Days of Obligation (1992). Casting his eye around him in central San Francisco, he begins by invoking Saint Augustine (and his thoughts on human restlessness and impermanence), then swerves into Elizabeth Taylor. During the 1970s, Rodriguez notes, gays began taking over the “storied houses” around him, as if not just to make over the all-American family home, but to rewrite the Victorian novel (the title of the essay conflates San Francisco’s quaint old buildings with the aestheticism that led into fin-de-siècle decadence). Typically, Rodriguez is unsparing on his own community: gays, in some respects, were just creating “dollhouses for libertines.” And American freedom can be a pretty word for loneliness: his own Victorian house has been “converted to four apartments; four single men.”

Just as you’re settling into a wry autopsy of a city and a lifestyle, though, he starts to light up his essay with italicized sentences from the obituary pages of local newspapers. One man after another is dying of AIDS. He has always styled himself as “the dinner party skeptic,” Rodriguez confesses, “a firm believer in Original Sin and in the limits of possibility.” Certainly he has often sounded like the token odd man out, murmuring “Et in Arcadia ego.” At the beginning of the essay he’d stated, “The point of Eden, for me, for us, is not approach but expulsion.”

Yet as his friends keep disappearing, one by one, the lonely moralist has to ask himself about the consequences of his detachment. “The greater sin against heaven,” he comes to think, “was my unwillingness to embrace life.” And as all kinds of neighbors rise up around him—young and old, straight and gay, rough-hewn and fancy—to volunteer their services to the dying, he has to wonder why he’s sitting alone on his “cold, hard pew.” The man so determined to go his own way has to count the costs of keeping community at a distance—and of his seeming prudence.

By ow, working with surreptitious precision, Rodriguez has brought out one book every decade, each of them addressing a central aspect of the American story: class, sex, and race so far. The new one claims to be about religion. But of course it’s a central feature of his thinking that nothing—not even loneliness—is ever considered in isolation. Rodriguez seems to have an aversion to the unmixed.

Thus even as the book with the ceremonial Catholic title Days of Obligation kept on referring to sex, so his new one, which purports to be about the desert monotheisms, calls itself Darling. Sometimes such gestures may strike readers as a bit much, but to his credit, Rodriguez does not try to link earthly and heavenly love as John Donne does, or to blend them with the abandoned ease of the Islamic high priest of Californian fashion, Rumi. Nor does he follow the familiar path of a gay believer wondering why the religion he serves so faithfully is ready to exile him for his sexual preferences.

Rather, this unpredictable maverick throws all his variegated interests into the mix and lets the sparks fly. He’s irreverent even toward the objects of his reverence—“Is God dead?” he sincerely asked in his first book—and grave about those issues (computer technology) that others might be flip about. When fondly recalling the Sisters of Mercy who educated him, he suddenly turns to the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of gay drag queens whose wild impiety he’d once written against. Now, however, as he watches them rattle cans for charity and jolly along some homeless teenagers, he has to concede that good works can make even the most outrageous poses irrelevant.

Darling begins by asserting that it will address the world in the wake of September 11 and try to bring the writer’s Catholicism into a better relation with its desert brother Islam. Happily, it soon abandons that somewhat rote mission for a much more ungovernable and unassimilable wander across everything from the decline of the American newspaper to the debate over gay marriage, from Cesar Chavez to the world of camp. Five of the ten essays have appeared already in magazines, such as Harper’s and The Wilson Quarterly. But as in all his books, Rodriguez throws off a constant fireworks display of suggestions and reveals more in an aside than others do in self-important volumes. As you read, you notice how often Don Quixote keeps recurring, and death notices, and meditations on the “tyranny of American optimism,” each one gaining new power with every recurrence, and reminding us of how the pursuit of happiness leaves us sad. The overall mosaic is far more glittering than any of its parts.

Advertisement

Here, for example, is a somewhat typical paragraph from near the beginning of the book:

Most occidental Christians are unmindful of the orientalism of Christianity. Over two millennia, the locus of Christianity shifted westward—to Antioch, to Rome, to Geneva, to the pale foreheads of Thomistic philosophers, to Renaissance paintings, to glitter among the frosts of English Christmas cards. Islam, too, in the middle centuries, swept into Europe with the Ottoman carpet, but then receded. (On September 11, 1683, the King of Poland halted the Muslim advance on Europe at the Gates of Vienna.) Only to reflux. Amsterdam, Paris are becoming Islamic cities.

Every sentence, you notice, advances a different idea, and each of them points in a different (somewhat contradictory) direction. Much like the chapters in the book, in fact. Specifics and pungent ironies are in evidence, but clearly the writer is more interested in larger themes: the currents of history, the extent to which progress is cyclical, the trade routes of faith. There is none of the careful research and reportage that would help advance an empirical argument; in fact, this writer may not be trying to persuade you at all (Rodriguez, one feels, might be disappointed if one agreed with him and so stripped him of his loneliness). Rather, he’s trying to get you to think, and to rethink what you thought you knew, a little as D.H. Lawrence does in his Studies in Classic American Literature.

All these lofty abstractions are brought down to earth, however, and given real weight—Rodriguez is unusual in being at once so tough-minded and so open to emotion—by their grounding in pieces of the author’s own life. His first book won many friends—and enemies—by turning its back on affirmative action. But at a deeper and more telling level, it was about the ways in which Rodriguez’s education had cut him off from his parents, his roots, even as his religion kept him apart from his worldly brunch pals. The heart of his second book was an exchange between the fourteen-year-old California-born author and his fifty-year-old Mexican-born father on whether life is tragedy or comedy. Is perfection possible? Someone from the Old World might say no, yet he’s surely come to the New World in part in the hope of being proven wrong.

That same dialogue sits behind much of what he writes in Darling. “As an American, I have never found an easy rhyme between my religion and my patriotism,” Rodriguez writes (again refusing to concede religion to the right). The very hopefulness that America decrees, the notion that tomorrow will be better than today, flies in the face of his Catholic sense of fallenness and the vanity of human wishes. Everything he reads in Emerson undoes what Saint Augustine has told him. The book itself is at times Augustinian confession, at times a flurry of one-liners that might have come from the homilist who wrote Representative Men. Catholicism may be Islam’s brother but—as Rodriguez suggests by circling back to his own brother, a former seminarian and now devout “anti-theist”—siblings can be opposed more profoundly than enemies are.

It can take a little while to adjust to the ways of such a nonlinear thinker, moving in circles and proceeding through indirection, implication. The words that come to mind, reading Rodriguez, are classical ones—memento mori, examen, sub specie aeternitatis—even as he often reflects on Liberace or “the post-lapsarian actress Tallulah Bankhead.” As he regularly reminds us, he’s writing inside a nineteenth-century house within a flagrantly twenty-first-century city. The range in all his pieces is unapologetically wide, as befits a former doctoral student in Renaissance literature and Fulbright fellow at the Warburg Art Institute: in writing on Las Vegas he alludes to Samuel Johnson, links a casino pirate ship to a passage in Tolstoy, and associates the casino owner Steve Wynn, thanks to his retinitis pigmentosa, with Tiresias. In his third book, Brown: The Last Discovery of America (2002), Rodriguez described the future of America not with a trendy reference to “hybridity”—or multicultural fusions—but rather by invoking Whitmanic self-contradiction.

This determinedly oblique way of approaching things means that a reader has to remain constantly on alert and ready for surprise. In an essay here on Cesar Chavez—it’s called, with many levels of irony, “Saint Cesar of Delano”—Rodriguez suggests that the cofounder of the United Farm Workers union is most to be cherished for his imperfections; if he’s close to a savior—worthy of beatification—it’s only because Jesus is “the most famous loser on a planet spilling over with losers.” Half monk and half tyrant, in Rodriguez’s reckoning, Chavez was the victim of his own high-mindedness. Yet the division within him is one that the author feels acutely: “For it was Mexico that taught Chavez to value a life of suffering. It was America that taught him to fight the causes of suffering.”

Such provocations are, inevitably, going to sound too broad for some, especially when delivered ex cathedra. Yet much of Rodriguez’s singularity comes from the fact that he clearly admires goodness but has little time for purity. You have to read him slowly, as you would a poem translated from the Spanish, with an eye to the glancing themes that develop between the lines. In the central essay, he starts describing how he used to meet a woman, somewhat secretly, at a hotel north of Los Angeles. When he dwells on the name of the place—the Garden of Eden—you may get a better sense of why John Milton recurs again and again in these pages. Rodriguez is an unusual modern American in thinking that man should be seen as less than he thinks, not more. And when he starts writing about the death of newspapers—rooting it in the fact that unpaid obituaries are disappearing—you start to notice how much is going on in a sentence such as “A newspaper’s morgue was scrutable evidence of the existence of a city.”

Met in an essay on the end of the classic newspaper, such a pronouncement would seem a stylish and perhaps self-conscious way of telling us what we know already. Met in the context of a book that insists on registering one death after another, you realize that the words and the example have been chosen carefully.

This makes for a high thread count in these essays: each one is clear and readable enough to be taken in quickly in a magazine, but all are so intricately stitched and woven together that they keep disclosing new, half-covert patterns. Besides, all the essays are performances in a way—the first chapter of Rodriguez’s first book was called “Aria”—yet each one is shot through with a sudden, piercing intimacy, as if a rather flamboyant Jeremiah were to leave his lectern every now and then and kneel down in a confessional.

The sweeping Olympian tone is guaranteed to put some readers on guard: how can a writer forty-five minutes by car from Silicon Valley write, “What is obsolete now in California is the future” and “California is finished”? Others may find that the author goes too far in his keenness to be fresh: the September 11 attacks, he writes, moved him to “consider the future in terms of a growing, worldwide female argument with the ‘natural’ male doctorate of the beard.” When he writes of the desert, “There is not another ecology that so bewilders human vanity,” it’s hard not to think, “What about the Antarctic? The Himalayas? The redwood groves or Pacific Ocean so close to the author’s home?”

Yet it’s precisely his readiness to dare something new that keeps Rodriguez—and his reader—alive; he’s constantly trying to slap us awake. And it’s the very self-questioning nature of his explorations that makes him, he might say, so deeply American. Bringing a literary voice to political issues and declining to pursue any single theme through analysis or straightforward narrative, Rodriguez writes like no one else, yet seems to belong with our most important essayists.

His constant, agonized cross-questioning of Californian blitheness—spiked with a willingness to locate the fault lines of that vision within himself—brings to mind another writer raised in Sacramento, only ten years older than he, Joan Didion. His readiness to hold America up to an old European standard and to rejoice in mixing up references to Andy Warhol’s Leonardos with sober investigations of the West Bank have something in common with Susan Sontag, though Rodriguez’s delight in undercutting both himself and his seriousness offer a sense of mischief and Wildean lightness Sontag less often admits to. And as he keeps questioning his religion, quizzically registering Pope John Paul II’s ninety-one formal apologies and trying to see how folly can fit with belief, he sounds at times like Annie Dillard, so committed to her faith that she seldom lets it off the hook.

It’s surely no coincidence that all three examples I’ve chosen are women: at the heart of Darling lies Rodriguez’s typically counterintuitive sense that women may be the saving of his church. The book is dedicated to the Sisters of Mercy who taught him; the title essay plays with the ambiguity of his closeness to a woman with whom he is, in many senses, a “pretender,” more than friend but never quite boyfriend. As the book draws toward its conclusion, he starts to reflect on Mother Teresa, whom he seems to admire mostly for the sense of spiritual desolation that overcame her the moment she received permission to start her new order.

Much earlier, writing on Jerusalem, he’d declared, “The blasphemy that attaches to monotheism is the blasphemy of certainty.” And then: “Certitude clears a way for violence.” Startling words from one who begins his book by professing his worship of God. Many a believer would surely find such words heretical, and many a nonbeliever would point out that doubt and self-division can lead to violence, too.

Yet this refusal to settle for easy answers or fixed assumptions is exactly what makes Rodriguez so essential. And his dislike of lazy pieties and sacred cows makes his restless books (his essays, his sentences) look stronger and more durable the more you see them as all of a piece. Over thirty years now, he’s maintained a fierce, rigorous, ironic, and sincere cross-examination of both contemporary America and himself. This would be bracing in any age, but never more so than in a time of talk-show simplicities and chat-show self-affirmations, when it’s ever easier to take shelter in the refuge of group-think.

At the very end of his new book, Rodriguez moves on from Bertrand Russell to Christopher Hitchens, and one half expects him to tear to pieces, as he easily could, the rampant inaccuracies and failures of comprehension that bedevil almost every page of Hitchens’s God Is Not Great (2007). As ever, however, he decides to forego the prosecutorial case many a conventional essayist might embrace. Instead, he recollects a brief meeting with the late polemicist in an elevator, and recalls Hitchens’s grandstanding attacks on Mother Teresa. Are such public triumphs ultimately more useful than a nun’s inner failures, the essayist asks? In the end, Rodriguez seems to favor the deeply flawed woman of faith over the champion debater if only because of one central distinction: her readiness to spend her days in “terrible darkness,” abandoned by her God, yet continuing along her path, determined to question that which she cherishes most.