1.

In recent weeks, Iran and the United States, for the first time, have broken through more than a decade of impasse over Iran’s nuclear program. Significant differences remain, but at long last, both governments appear ready to work their way toward a resolution. Yet the US Congress, acting reflexively against Iran, and under intense pressure from Israel, seems ready to shatter the agreement with a bill that takes no account of Iranian political developments, misunderstands proliferation realities, and ignores the dire national security consequences for the United States.

By November 2013, when Iran and the P5+1 group (the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France, and Germany) announced that they had arrived at an interim deal on Iran’s nuclear program, it had been thirty-three fractious years since Washington and Tehran had reached any kind of formal agreement.

During that long hiatus, the American enmity and distrust of Iran that stemmed from the 1979 hostage-taking had hardened into a one-dimensional view of the Islamic Republic as wholly malign. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Holocaust denial and vicious rants against the existence of Israel confirmed Americans’ worst fears.

On the Iranian side, the list of real and perceived injustices was much longer, beginning with the US-backed overthrow of Prime Minister Muhammad Mossadegh in 1953, US support for Saddam Hussein during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War, in which as many as one million Iranians may have died, and the destruction of an Iranian civilian airliner and its passengers in 1988. Iranians called the US the Great Satan. The US named Iran as part of the Axis of Evil. For most of these decades, even a handshake between officials was taboo and an Iranian who advocated improving the relationship could find himself in Evin prison.

The greatest single cause of friction was the growing evidence that in spite of having signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1968, Iran was in fact pursuing nuclear weapons. For more than fifteen years, intelligence and on-the-ground inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) revealed nuclear facilities, imports of nuclear technology, and research that had no civilian use. The scale of Iran’s programs that could have both peaceful and military uses, notably uranium enrichment, was wholly out of proportion to any reasonable civilian need. The IAEA tried for years without success to get answers to a growing list of questions about the possible military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear program.

Europeans tried repeatedly to negotiate a solution. In the end, their efforts went nowhere. There were mistakes on the Western side, especially the coupling of extreme demands with minimal incentives for the Iranians. But it also became clear that the Iranian side was not negotiating in good faith. It was simply using the enormous time consumed in fruitless talks to advance its nuclear program.

Through these years American sanctions did slow Iran’s progress. During the Bush years the sanctions were largely unilateral because most countries held the view that the US was unreasonably trying to block Iran from nuclear activities that were within the limits of the NPT. Not until President Obama made it plain, beginning in 2009, that the US was willing to enter a serious dialogue with Iran and that it was the mullahs who could not “unclench their fist” did the weight of international opinion swing against the Iranian government. Since then, the United States has led the imposition of broad international sanctions of unprecedented severity. These have slashed Iran’s oil exports by nearly two thirds and imposed bans on Iran’s banking sector that cut off the country financially. The Iranian rial lost 80 percent of its value. Inflation and unemployment soared.

Thus, the sanctions drastically raised the cost to Iran of seeking nuclear weapons in violation of its treaty commitment. In addition to the sanctions, cyberattacks on Iranian nuclear facilities, such as the malware program Stuxnet, assassinations of Iranian scientists, and other covert action also slowed the program’s progress. But sanctions were not able to stop Iran from steadily increasing its enrichment of uranium toward the threshold level to fuel a weapon. Iran had about two hundred centrifuges for enriching uranium operating in 2003. When President Bush left office it had seven thousand. Today it has nine thousand first-generation centrifuges spinning, eight thousand installed and ready to go, and one thousand much more capable second-generation units. Its stockpile of low-enriched uranium—suitable for use both as reactor fuel and for further enrichment—has grown to more than ten thousand kilograms, a tenfold increase since Obama took office. And Iran now has roughly two hundred kilograms of uranium enriched to 20 percent. If that amount were further enriched to the 90 percent level required for a nuclear weapon, it would be close to, but still short of, one bomb’s worth.

Advertisement

Exactly how long it would take for Iran to make a dash for a nuclear weapon is unknown. Generally, the limiting step is acquiring enough weapons-grade fuel, so it could be as little as a matter of weeks. However, a single untested weapon is of little or no military value.

2.

Reduced to essentials, the struggles of the past decade come down to a few basic realities, now discernible in both Tehran and Washington. Unilateral sanctions accomplish little. Multilateral sanctions that are broadly enforced can have a devastating impact on the Iranian economy, but even these cannot stop a nuclear program if Tehran chooses to pay the price. Iran has responded to international threats and pressure by increasing its efforts—more centrifuges, new covert facilities, larger stockpiles of enriched fuel. These advances elicit greater foreign pressure, and so on.

No outsider can say for certain that Iran ever definitively chose to become a nuclear weapons state. On the one hand, it has spent billions of dollars pursuing activities that can be rationally explained only if the regime seeks the ability to produce weapons. And as a result Iran has forgone hundreds of billions of dollars worth of oil revenue owing to sanctions.

Yet Tehran has also said that it does not want nuclear weapons. It has argued that nuclear weapons would not be appropriate for an effective military strategy and that they would violate the principles of the Islamic Republic. The Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, at one point issued a fatwa to this effect. US intelligence concluded in 2007 and has reaffirmed twice since that while Iran continued to enrich uranium beyond its civilian needs, it had abandoned its weapons pro- gram some years earlier. No country is a monolith, especially not Iran, a country with a byzantine, multilayered political system. Some officials may have wanted Iran to be a nuclear weapons state. Others may have wanted the so-called “Japan option,” to be technologically able to make nuclear weapons but stop short of doing so. It is possible that a single, definitive choice was never reached or that it has changed over the years. It is also possible that nuclear weapons capability has been the certain goal throughout.

But Iran has been unambiguous in insisting on its right to uranium enrichment. As international opposition to its nuclear activities deepened, enrichment—allegedly for peaceful purposes—became the symbol Iranian officials fastened onto in their defense of the program. They portrayed it as a matter of national pride, international standing, and technological prowess: arguments that command strong public support in Iran. For some years it has become clear that if a negotiated settlement to the nuclear standoff was ever to be reached, allowing Tehran some degree of enrichment would have to be a part of it. After all the resources that have been spent, international acceptance of Iran’s enrichment program would be the measure by which Iran’s leaders could claim victory to their public. Those like Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who insist that the only acceptable level is zero enrichment in Iran know, or should know, that they are using code for “no deal would be acceptable.”

Beyond that, however, the question that has elicited so much misplaced passion, of whether Iran has the “right” to enrichment, is a red herring. There is no formal, legal “right” to enrichment or any other nuclear activity. All that the NPT says is that parties to the treaty have “the inalienable right…to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination.” Enrichment is certainly encompassed within these words but the qualifier—“for peaceful purposes”—is crucial. If the world becomes convinced that a non–nuclear weapons state’s activities are directed toward acquiring nuclear weapons, such activities thereby become illegal. So while Iran cannot claim a legal “right” to enrich, it can claim the right to do so in the colloquial sense, for it is a fact that eight other non–nuclear weapons states—Japan, Brazil, Argentina, the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Belgium, and Italy—currently enrich uranium without international complaint. None of them would willingly give up the option to do so.

We might wish in hindsight that the NPT had been written so as to tightly restrict dangerous, dual-use technologies like enrichment that provide direct access to weapons fuel. But as the law stands today, there is no ground for restricting a peaceful nuclear program in Iran to zero enrichment. The question is whether the program can be restricted to peaceful activities and whether the world can be assured that it will stay that way.

3.

By the beginning of 2013, the tit for tat exchanges of international pressure and Iranian progress on the ground had escalated to nearly twenty thousand centrifuges in Iran, more than one hundred billion dollars in sanctions, and growing talk of war. Three paths forward were possible: more of the same, leading eventually to an Iran that is either a declared or an implicit nuclear weapons state; a negotiated resolution; or an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities. All have high costs. Some would have hideous consequences. As their merits are debated, the question “Good or bad as compared to what?” must constantly be asked, for these are the only three choices.

Advertisement

A case can be made that the world, including the US and Israel, could live with a nuclear-armed Iran. History proves that deterrence and containment work. But it also points to the fact that proliferation doesn’t happen one state at a time. It proceeds in clumps. The US and USSR prompted China to go nuclear. China prompted India to do so, which in turn prompted Pakistan. Brazil and Argentina began to cross the line together and stepped back together. Even if deterrence kept Iran from ever using a nuclear weapon, it is likely that nuclear weapons in Iran would prompt others in the region to follow suit in an effort to equalize power. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt are the most likely.

The Middle East is already riven by the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, by Sunni-Shia rivalry, and by the divisions and distress unleashed by the Arab Awakening. The prospect of nuclear weapons in the hands of several states—not only Israel and Iran but others as well—can only be contemplated with dismay. Moreover, a nuclear Middle East would probably lead to proliferation elsewhere. Only four countries have crossed the nuclear line since the original five nuclear powers half a century ago. If three or four were quickly added to the list, it could well mean the end to the decades-long international effort to halt proliferation.

This effect on proliferation in the region and beyond is enough to make a nuclear Iran a clearly undesirable outcome. There are, then, two remaining choices: an agreement or an attack. A negotiated agreement would be imperfect. Sustained vigilance would be required, and a degree of risk would remain, for an agreement would be a compromise, not a surrender. So one might begin by asking whether an attack looks more promising.

Even the strongest proponents of air strikes against Iran’s known nuclear facilities do not argue that the result would guarantee anything more than a delay—perhaps two years or somewhat longer—in Iran’s program. Facilities can be rebuilt and physicists and engineers would continue to have the expertise needed to make nuclear weapons. After years of effort, Iran can now make at home most of what it needs to build a bomb.

When the program is rebuilt after an attack there would be no IAEA inspectors and no cameras to monitor its advance, since monitoring depends on cooperation. As outsiders attempted to track the reconstituted program and prepare for another round of attacks, they would know far less than we do today about the scale, scope, and location of what is happening.

The political consequences would be longer lasting. An attack is likely to unite the country around the nuclear program as never before. The hardest of Iran’s ideological hard-liners would be strengthened against those who had advocated restraint and reconciliation, thereby radicalizing and probably prolonging clerical rule. Following air strikes, it would be easy for Iranian leaders to make the case that the country faces unrelenting international enmity and must acquire nuclear weapons in order to deter more attacks.

Some advocates of war have evoked rosy but utterly unconvincing scenarios in which Iran’s current regime collapses after a limited air attack and is then succeeded by a government that suddenly cries uncle. Such an argument is hard to make with a straight face. Only an invasion with ground troops, followed by a long occupation (in a country of some 80 million people, three times the size of Iraq), could force an end to the Islamic Republic. Otherwise, the odds are overwhelming that a successor government, if one were to take power, would be more, not less, committed to acquiring nuclear weapons.

The broader geopolitical and strategic consequences would depend entirely on what prompted the attack. Going to war against an Iran that is making a dash to actually build nuclear weapons might have substantial international support. An attack on Iran because it refused to give up uranium enrichment, however, would be very widely seen as illegitimate. It would be another preventive war, like America’s invasion of Iraq, against a potential, future threat. Unlike a preemptive response to an imminent threat, preventive war has no international legitimacy.

If an attack were made, in effect against enrichment, the sanctions now in place against Iran would collapse. Countries like Russia, China, Turkey, India, and Japan that have adopted the oil and financial sanctions against Iran with varying degrees of reluctance are unlikely to sustain them to support a war against enrichment. If Iran were seen as seeking or upholding a negotiated solution when it was attacked, the attackers would likely find themselves international outcasts.

Iran could retaliate in many ways—through direct military action and by using Hezbollah and other proxies in terrorist acts. Even apart from those consequences, a military attack that leaves Iran without inspections and without effective sanctions while radicalizing its government and convincing much of its public that only nuclear weapons could defend them, all for the delay of a few years in its program, would be irrational, except, perhaps, as a last resort. Even then, balancing the pluses and minuses of such a war against those of living with a nuclear Iran is for many analysts a very close call.

4.

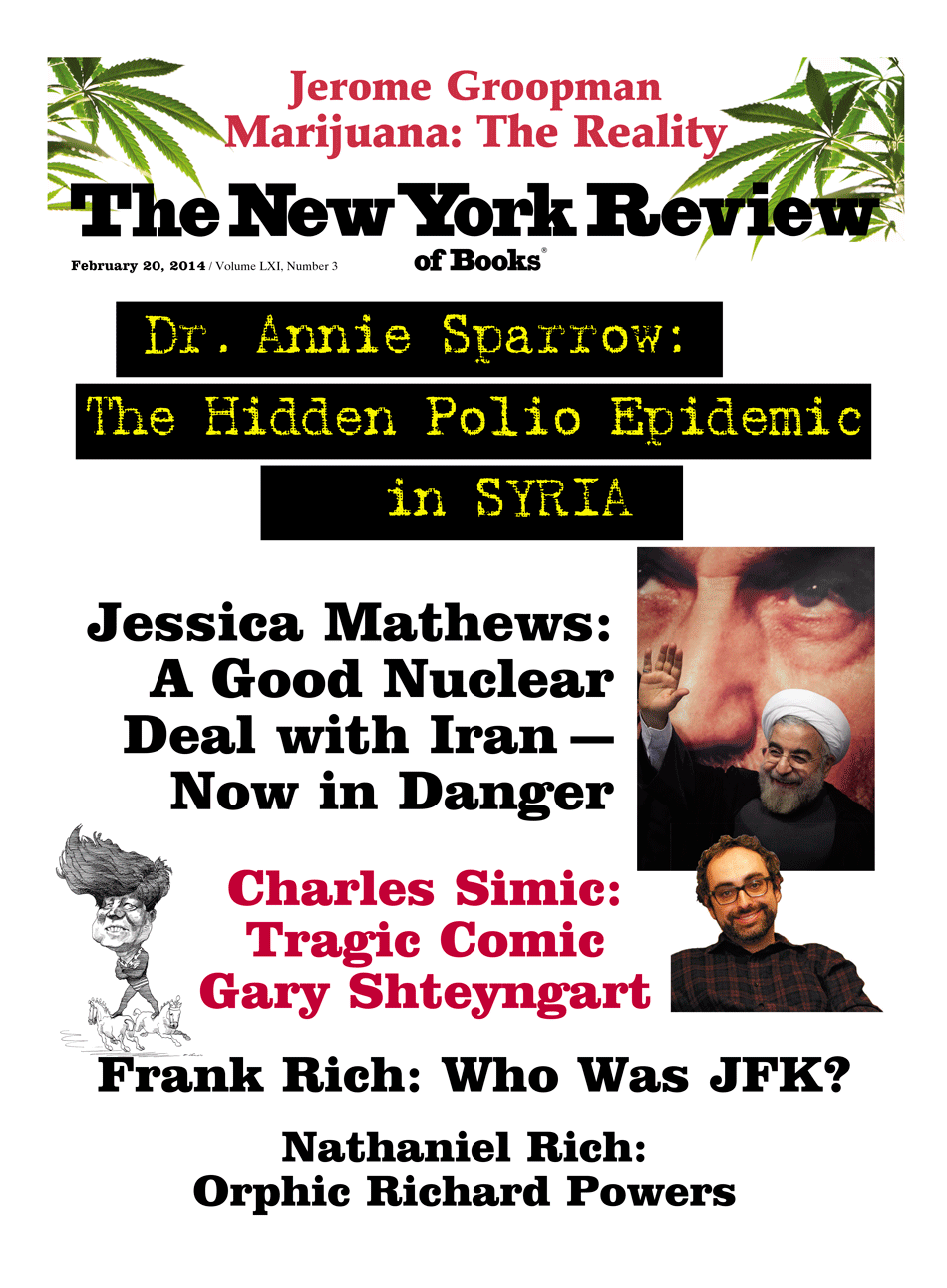

This brings the story to the stunning surprises of 2013, beginning with Iran’s June election in which Hassan Rouhani, confounding poll results and universal expectations, won a majority among six presidential candidates, with just over half of the vote.

Iran has a bizarre combination of authoritarian rule and active politics. Thus the Guardian Council, under the direction of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, disqualified 678 of the 686 individuals who applied to run for office. Yet in the campaign, those who did get to run took specific positions and vigorously debated them. The foreign policy debate, televised nationwide, went on for three hours. Voter turnout at 75 percent was almost half again higher than in the United States in 2012.

Rouhani campaigned for greater moderation in government, “an end to extremism,” and flexibility in reaching a nuclear accommodation in order to end Iran’s international isolation and stalled economy. A cleric and senior member of the ruling inner circle and a personal friend of the Supreme Leader for forty years, he is an advocate for change in both foreign and domestic policy, but very much a member of Iran’s political establishment. Speaking fluent English, he served as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator a decade ago.

The mandate of the election was clear—not to dismantle nuclear facilities, end enrichment, or surrender Iran’s rights as Iranians see them, but to seek an agreement through flexibility and moderation. The Supreme Leader underlined the point, calling for “heroic flexibility.” And while the outcome of the election was greeted with joyous celebrations in the streets, Rouhani has powerful enemies, the Revolutionary Guard among them, who have made no secret of their hope that he will fail. He has to deliver results reasonably soon, or he will be ousted.

His first step was to appoint Iran’s most talented diplomat as foreign minister. Javad Zarif impressed the world in his years as Iran’s representative to the UN; after living for many years in the US, he understands its politics well. With the Supreme Leader’s blessing, Rouhani then transferred the nuclear portfolio from the hard-line Supreme National Council to the Foreign Ministry, which reports to him. He changed the government’s tone radically. Though still an enemy, Israel was no longer “the Zionist entity” but the state of Israel. Just after he won the election, Rouhani tweeted a picture of himself visiting an American-supplied field hospital in southeastern Iran some years before.

Initially, these and other moves were dismissed by critics as a “charm offensive.” In an unusually intemperate speech to the General Assembly, Netanyahu warned that Rouhani was a “wolf in sheep’s clothing” set on duping the international community. But as the weeks passed and Iranian acts added up, most had to conclude that, unlikely as it seemed against the pattern of past decades, this was in fact an Iranian administration with new goals that had, at least for a time, the backing of the Supreme Leader.

Through the fall, negotiations in Geneva accelerated, often stretching around the clock. On November 24 came the announcement of a first-phase, six-month nuclear deal to be followed by a more comprehensive, permanent agreement six months or a year later.

The essential elements of a bargain acceptable to the P5+1 negotiators were well defined in advance. To prevent Iran from once again using the negotiations to buy time to advance its program, Tehran would have to agree to halt production of 20 percent highly enriched uranium. It would have to keep its capacity for enrichment stable by stopping the operation or the installation of additional advanced centrifuges. It would have to halt progress on the reactor under construction at Arak that is designed to produce plutonium, also a weapons fuel. Specifically that reactor could not be fueled or turned on so that, if the agreement were ever violated, it could be bombed without spreading radiation.

The actual agreement goes far beyond this. Most important, and perhaps most unexpected, Iran agreed to eliminate its existing stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium either by diluting it down to low enrichment or converting it to an oxide form that is not adaptable for further enrichment. Netanyahu had famously held up a cartoon poster of a bomb before the General Assembly with a red line drawn across it at the threshold level of 90 percent enriched uranium. The agreement takes Iran’s less enriched stockpile to zero.

The terms also provide that Iran can build no additional centrifuges except to replace broken ones. While existing centrifuges may continue to spin, the product must be converted to oxide so that Iran’s stock of low-enriched uranium does not grow. The agreement bans the testing or production of fuel and new components for Arak and requires Iran to turn over important design information that will help the IAEA safeguard the reactor there.

To strengthen the assurance that all this will happen, the agreement requires daily access for inspectors as well as downloads from cameras used for surveillance, including at the Fordow underground enrichment plant. To reduce the possibility that Iran could be running covert, hidden fuel cycles, it extends monitoring for the first time to uranium mines and mills and to centrifuge production and assembly facilities. These inspections are unprecedented in both frequency and extent.

In return, the P5+1 agree to lift about $7 billion worth of sanctions, though leaving the most important oil and financial sanctions in place. Further, the US and its allies pledge not to impose any new nuclear-related sanctions while the agreement is in effect.

There is much left to be dealt with in the permanent agreement. In the view of the P5+1 negotiators, Iran must permanently cap enrichment at 5 percent and reduce the size of its stockpile, which holds far more low-enriched uranium than it needs for any foreseeable peaceful purpose. Similarly, the total number of centrifuges needs to be proportional to civilian needs. The Arak reactor must be defanged—most likely converted to a different design. And the final agreement must deal with Parchin and perhaps other facilities where research and development directly related to making weapons are believed to have taken place.

What remains to be done does not diminish the historic dimension of what has been achieved. After more than a decade of failed negotiations and, for the US and Iran, three decades of unproductive silence, diplomacy is working. As of January 20, 2014, the short-term agreement is in full effect. Twenty percent enrichment is suspended. If the agreement is sustained by both sides, Iran’s enrichment progress will be halted and in important respects rolled back. The time it would take to break out and dash for a nuclear weapon is lengthened by perhaps two months and the new inspection requirements mean earlier warning of danger and more time to respond. In return, the P5+1 gave remarkably little. Indeed, this deal only becomes attractive for Tehran if it is followed by a permanent agreement that brings major relief from sanctions.

Nevertheless, Prime Minister Netanyahu greeted the agreement with a barrage of criticism. Even before it was completed he called it a “Christmas present” for Iran; later, “a historic mistake.” His too attentive audience on Capitol Hill followed suit. Many of the criticisms suggest that the critics haven’t appreciated the terms of the agreement. Senator Charles Schumer dismissed it as “disproportionate.” The observation is correct, but upside down, for Iran gave far more than it got.

Others vaguely suggest that Iran will inevitably cheat. To oppose the deal on this ground, one would have to be able to explain why Rouhani, if his intention were to cheat, would sign a deal that focuses the world’s attention on Iran’s nuclear behavior and imposes unprecedented inspections and monitoring. What would be the logic in that? Iran has inched forward successfully for years. Why invite severe retribution by making an explicit deal with the world’s major powers and then violating it?

More serious are those who, wittingly or not, argue that there should be no deal. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, for one example, demands that Iran “irreversibly dismantle its nuclear stockpile [i.e., of enriched nuclear fuel] and not be allowed to continue enrichment.” Those who take this view must either believe against all experience that Iran can be threatened into submission or favor a war whose foreseeable costs are wildly disproportionate to its possible gain. The less attractive explanation is that such critics are not thinking beyond the immediate satisfaction of railing against Iran—a kneejerk political habit after thirty years—and scoring political points (and campaign dollars) as a resolute supporter of Israel.

A bill that is so convoluted and poorly drafted that many don’t understand that it would automatically apply new sanctions has gained fifty-nine cosponsors in the Senate—close to veto-proof support. The language violates the first-phase agreement by imposing new sanctions (if, for example, a Hezbollah attack anywhere in the world were to damage US property) and makes a permanent agreement unachievable by apparently requiring the complete dismantling of all enrichment facilities.

The bill’s authors, Senators Robert Menendez and Mark Kirk, argue that it strengthens the president’s hand. It does the reverse by making even more acute Iranian doubts that the president can deliver the relief from sanctions they are negotiating for. Its passage, as an act of bad faith on the US’s part after having just agreed not to impose new sanctions during the term of the six-month deal, would probably cause Iran to walk away from the negotiations. Rouhani would risk political suicide at home if he did not. Alternatively, in the all too familiar pattern of the past decade, he might stay at the negotiating table and match unacceptable American demands with his own so that blame for failure would be muddled. America’s negotiating partners and others whose support makes the sanctions work would feel the sting of bad faith as well. The sanctions regime that has been so painstakingly built through ten years of effort by determined American leaders of both parties could easily unravel.

The bill’s most egregious language explains why so many senators leapt onto this bandwagon: it has become a vehicle for expressing unquestioning support for Israel, rather than a deadly serious national security decision for the United States. The US, according to this provision, “should stand with Israel and provide…diplomatic, military, and economic support” should Israel launch a preventative war against Iran in what it deems to be self-defense. Though this language is in the nonbinding “Findings” section of the bill, its sense is to partially delegate to the government of Israel a decision that would take the United States to war with Iran. Senators report that AIPAC’s advocacy of the bill has been intensive, even by its usual standard.

In the end, this seemingly complicated story is actually quite simple. For the first time in decades, the US has an opportunity to test whether it can reach a settlement with Iran that would turn what may still be an active weapons program into a transparent, internationally monitored, civilian program. The pressure of multilateral sanctions, the president’s willingness to engage in serious negotiations, and the change in Iran’s domestic politics have come together to produce this moment. A final agreement is by no means assured, but the opportunity is assuredly here. The price of an agreement will be accepting a thoroughly monitored, appropriately sized enrichment program in Iran that does not rise over 5 percent. The alternatives are war or a nuclear-armed Iran. Should this be a hard choice? Astonishingly, too many members of Congress seem to think so.

—January 21, 2014

This Issue

February 20, 2014

The Hidden Polio Epidemic in Syria

In the Shadow of Sharon