Dystopian novels portray a society, usually of the future, that has arrived at the destination we’re all headed for if we don’t change now. The great dystopian novels and the scary developments they portray convince us of things that are all too possible in the society we live in, if we hadn’t spotted them for ourselves. The most shocking dystopian novel is the first one you read, when the whole idea of the arbitrariness of human arrangements comes over you, with the realization that the future is contingent on the present, and can be affected by something you do or don’t do now.

For people of a certain age, that seminal reading experience is likely to have been one of the classics—Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels or George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four or Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451—while younger people may have started with something like The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. Chang-rae Lee is to be included in a list of serious literary writers who’ve turned their hands to dystopia. He teaches in the creative writing program at Princeton and has won the PEN/Hemingway Award for one of his sensitive, quiet, engrossing earlier novels in the realistic mode, Native Speaker, and a number of awards for others of his novels, none prefiguring his new one.

This novel, On Such a Full Sea, is the picaresque tale of Fan, who has a one-syllable name, as is common in science fiction. Fan is a tiny young woman, a diver in the vast tanks where fish are raised that support the community of B-Mor, Baltimore that was in the olden days. Fan has slipped out of B-Mor to search for her lover Reg, who has disappeared. Reg, in most ways just a nice, regular guy, is unusual in being one of the few people to be free of the malady, C, that ultimately kills all citizens of B-Mor. After their one sexual encounter, Fan is pregnant with his child.

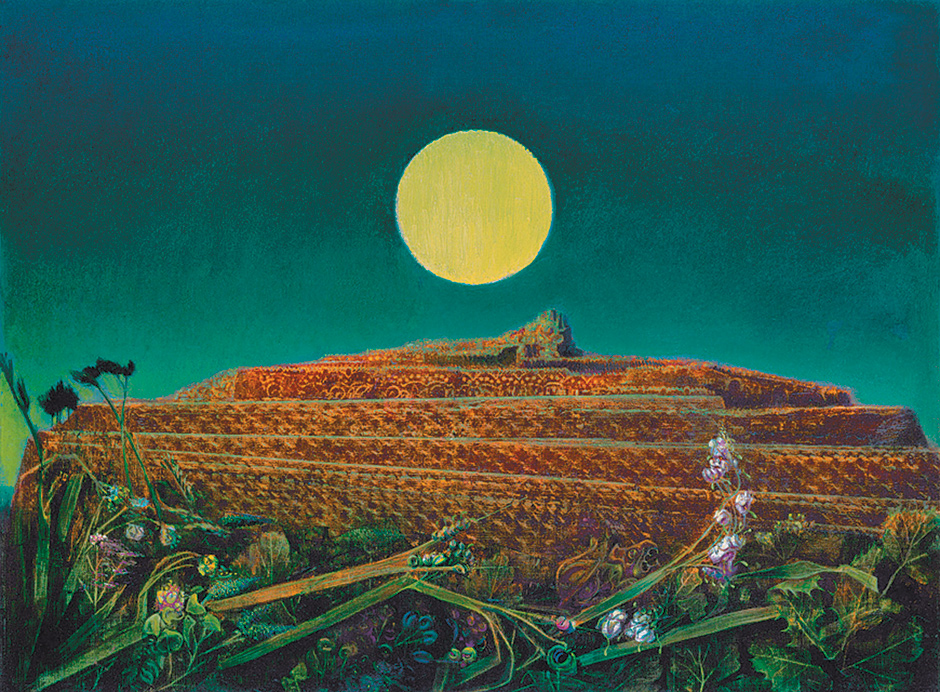

B-Mor is a community that fits into the tripartite cosmology common to many foundation myths, involving outer darkness, earth, and some sort of heaven. The regimented and futuristic B-Mor corresponds to earth. As a worker there, the narrator—who tells the story of Fan—knows the place was built on the ruins of the deserted former city and peopled with immigrants from a village in New China that had become uninhabitable with pollution. It’s a world that didn’t do anything about climate change:

Because it’s rarely pleasant out of doors, we’ve come to depend on the atmosphere of seasonally perfumed, filtered air and the honey-hued halo lighting and the constantly updated mood-enhancing music that all together are hardly noticeable anymore but would likely cause a pandemonium were they cut off for any substantial period.

What the characters take comfort in and consider desirable is usually made to sound repellent to us. We don’t really know who is running things—the state or oligarchs? Dictators or computer lords? Yet it’s apparently the fact of Fan’s leaving B-Mor that astonishes people; citizens seldom leave, and consider that their lives are as good as possible there, despite a faltering health care system and other problems we will recognize.

When people in B-Mor can better themselves by being among the few that pass certain academic exams, they of course seize the chance. Fan’s brother had been one of the chosen few, and had gone on to a Charter colony years before. In Lee’s system, the Charter colonies correspond to heaven—desirable settlements where the residents seem to lead normal urban lives of today. People have worries and mortgages, and sometimes kill themselves rather than run up medical costs. Charters are “modeled after” places that

you can really only see in movies now, communities where people strolled with shaggy dogs and children licked ice cream cones and where the benches were occupied by the contented elderly or smooching lovers and trains came….

Hell is outside the enlightened enclaves, rough “open counties” (“pleeblands” in Margaret Atwood’s cosmos, and Indian reservations in Brave New World). In such places, human nature is given free range. On her search for Reg, Fan has to venture into these scary territories, where the things that happen reflect the savagery but sometimes the kindness of human nature and where in her wanderings she has many sinister adventures: she survives a robbery; another time, she is nearly fed to dogs by a family of the desperate, brutish, cannibal humans living there. When she’s hit by a car, she is found by a couple, Quig and Loreen, open county people who take her first to their rough communities, and finally to a Charter colony, where people have a real-world range of kind impulses, perversions, ailments, and greed. There she makes friends who cherish and admire her.

Advertisement

Fan’s adventures can have something of the graphic quality and movement of a comic book, say Tintin. Fan gets into one scrape or another, escapes, and has close calls: Paff! Pow!! Aargh… But Lee’s novel is elevated above the merely eventful by the analysis and moralizing of the narrator, for whom the action is past but not yet fully explained, recounted the way we might recount the adventures of Ulysses or Roland, legendary heroes, without the option of having known them except by tradition and gossip.

The occasion of the tale is unclear: Is it a story being told to a group? “For all of us here, it is difficult not to think often about that first night of Fan’s.” The language of this narrator is not flashy, he never strives for effect: “her arms [are] crossed over her ample bosom,” or “for B-Mors, of course, it’s no big deal.” Fan’s escapades are punctuated by long passages of exegesis and reflection by this rather morose but folksy narrative voice, who poses some of the questions asked by the novel about the role of an individual in his society and the values of cooperation and collective behavior:

If you think about it, there’s little else that’s more important than having a schedule…; it helps one to sleep more soundly, to work steadily through one’s shift, maybe even to digest the hearty meals, and finally to enjoy all the free time available to us, right up to the last minutes of the evening….

Maybe it’s the laboring that gives you shape. Might the most fulfilling times be those spent solo at your tasks, literally immersed or not, when you are able to uncover the smallest surprises and unlikely details of some process or operation that in turn exposes your proclivities and prejudices both?

His discourse is one of the distinctive qualities of the novel, with the disadvantage that it keeps us at a distance from the main characters. Much as in chick-lit or westerns, the reader will look for an appealing character whose fate is in the balance; but we are prevented from getting close to the taciturn and enigmatic Fan. We have no access to her consciousness, and neither does he.

Other narrative devices too have this distancing effect, for instance, foreshadowing the action to come: “It is either outrageous fortune or destiny that Quig’s car struck and injured her that first night.” And because the action is set in the recent past of the narrator’s society, a tone of nostalgia complicates any presently engrossing events. The narrator’s resigned and reticent tone resembles that of the narrators in Lee’s previous novels A Gesture Life and Native Speaker, the voice of an older, Asian, solitary man talking about the past in almost Jamesian appositives:

There is always something entrancing about an image [painted] on a wall. Perhaps it’s because it’s frameless, threatening to break wider, maybe free. From the youngest to the oldest we know its purpose, which is to inspire and incite and celebrate, maybe question and even criticize, and then, of course, simply to record a version of what has happened, or should have happened, were our world a more genial place. And seeing those splashes of color along with others (or the thought of onlooking others) is totally different from seeing the same images alone, the former sensation, when it is right, akin to sharing a long-harbored secret.

Garrulous and pensive, but the narrator is nonetheless no Hegel. He rambles, and though his interpretations take up half the text, it’s not so clear what he’s getting at except a wistful and nostalgic account of better days and putting the best face on the present situation of his group, which fell into turmoil after Fan’s departure demonstrated that people could leave, could change, could choose adventure and risk over safety and routine. Fan’s departure stirred things up, “and yet here we are in the mall-going throng, like everyone else pursuing our day’s own trivial ends but feeling drawn in, too, by the wider pitch and tow.”

Orwell and Huxley, P.D. James and J.G. Ballard modeled their dystopic societies on England, but for more than a century, America has been a main target, the ur-dystopia, certainly for Margaret Atwood, as early as her 1972 novel Surfacing—but also, when you come to think of it, since Tocqueville, or Mrs. Trollope, who upon arriving by ship from England in 1827 remarked that she had “never beheld a scene so utterly desolate as this entrance of the Mississippi. Had Dante seen it, he might have drawn images of another Bolgia from its horrors.”

Advertisement

Lee is no exception in targeting contemporary America, but the Koreas too come in for their share of criticism as harbingers of a dystopic future. One thinks of Adam Johnson’s recent harrowing novel set in North Korea, The Orphan Master’s Son. Lee’s dystopia is strongly similar to some accounts of contemporary South Korea, where he was born in 1965, though he came to America at the age of three. One Korean-American writer, Euny Hong, tells us that historically

the Korean political system was a meritocratic aristocracy…all but the very lowest classes had the right to sit for the kwako…[an exam that] only a hundred or so people would pass, out of thousands of applicants.*

If you passed the exam you were elevated to the aristocracy, so parents sent little Korean children to after-school private academies, called hagwon, and special schools for memory training, often at great financial sacrifice. In Lee’s B-Mor people take the same test:

With the lowest-scoring decile put on a probationary list…or…slated for service jobs such as retail or teaching or firefighting, unless, of course, they inherit enough money to make a sizable contribution to the directorate…. Still, with the stakes so high, Charter parents will spend whatever they must to prepare for this, hiring developmental therapists and tutors…. As previously noted, one of ours must score in the top 2 percent…without any enrichment training or tutoring at all.

Rather like getting your kid into nursery school these days.

Maybe there are people who read dystopian tales for self-improvement the way people used to read sermons, or for amusement—people who can edit out the very details that have most preoccupied the person who made them up, and read for the story alone. The stories, boiled down, are usually at bottom just the good old stories. Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, set in London, is basically the same story as Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, set in the dystopian world of a mental institution; both Alex and McMurphy are forced into conformity and docility by institutional powers.

There are quest stories or love stories—a quest runs through Margaret Atwood’s trilogy about Crake and Oryx. Chang-rae Lee’s On Such a Full Sea is both a quest and a love story—a girl searches for her lover and for her brother, and so on. There’s no missing the appeal, especially for adolescents, of another common structure of these tales: a protagonist, often a teen, somehow preserved from the brainwashed docility of most people in his or her society—a rebel—solves some personal or social problem afflicting everyone (Hunger Games), and escapes from the future into what we recognize as a more normal world.

Utopias of course are just variations of dystopia, the reverse side of the same coin, in which a traveler from somewhere better tells about a distant society whose humanity and wisdom throw into relief the practices of our own, as in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, or William Dean Howells’s A Traveler from Altruria, when the disingenuously leading questions that the suavely persuasive traveler asks his American host expose American laws, tastes, and manners as a kind of dystopia next to the traveler’s ideal Altruria. Through three hundred pages, America is indirectly portrayed as a dystopia of hypocrisy and self-delusion, the way Brobdingnagians, Yahoos, Lilliputians, and Houyhnhnms threw light on Swift’s and Gulliver’s England.

For the writer, besides the fun of getting things off his chest, the pleasure must be in his own ingenuity, the inner consistency of the world he’s worked out, forecasting the logical evolutions of present conditions, making up the new names (B-Mor for Baltimore), finding the clever equivalences. A pitfall of dystopian novels is that their writers can become too absorbed in the details of their invented worlds, and in the inner consistency of their visions, which can produce long, perhaps, to some, uninteresting descriptions:

All the facility tanks are full again with every stage of them, from specks of fry to the stoutest matureds, the concrete floor of the grow houses tickling the feet with the constant vibrato of the filter pumps running around the clock, the air heavier, moister (though it truly can’t be, given how engineered everything is) with the enriched quality of the reprocessed effluent dripping onto the plant beds. These are growing as dense as ever, so that you can hardly see a coworker weeding directly on the other side, merely hearing the threshing of his gloved hands against the stalks.

No doubt there are readers for whom the technical details of a future world also explain its fascination. Urban children maybe, who must escape in avatars, games, and costumes because they have little chance to play outside. But most readers, I think, ignore the ray-guns and focus on the protagonists and villains, the fundamentals of storytelling. There’s an inherent difficulty in sharing someone else’s imaginary land: the farther it departs from what the reader knows, no matter how vividly described, the less telling it is. P.D. James’s familiar English world of tea parties and antique shops at a moment when something has stopped humans from reproducing, in her dystopian The Children of Man, is somehow scarier than Atwood’s pigoons, savage animals in her universe, but harder to envision as anything but cute piglets, pink and snorty.

If the wellsprings of novel-writing are mysterious, there’s surely a hint of admonition, and an admonitory project is especially clear in dystopia. A question is: Why write in an unlovable genre with an inevitably hectoring tone? Dystopia, situated in a dangerous no-man’s-land between the pulpit of the preacher and the safe sniper post of the satirist, seems to keep attracting adventurous novelists, luring them to their peril with the promise of freedom outside of the safe, familiar territory of realism. Those who dared have produced a few masterpieces that have permanently changed our awareness of various social dangers—Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four to name two obvious examples.

One can only guess what the attractions are for individual novelists of the generally repellent dystopias, and presumably the reason will differ from writer to writer; the reader senses that the psychic origins of Margaret Atwood’s elaborately worked-out dystopian MaddAddam trilogy (Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood, and MaddAddam) are not the same as Lee’s. All, no doubt, write from the shared sense of dismay about modern life, though few seem to take on the revolutionary stages by which the world arrived in its dystopian state—the climate change, hydrogen bomb, license, or tyranny that had precipitated the fall. Fiction doesn’t take things on in such vast scale. Either dystopias are logical extensions of today, recognizably ourselves only worse, or our present world is utopia compared to a future wrecked by science or some human tendency, usually greed or fascism, and sometimes science.

Finally, it may also be said that dystopic novels are probably more interesting the younger you are, with more of the future ahead of you; and depending on what your experiences have taught you about the likelihood that adults, society, the state, whoever, will likely muck the future up for you before you get there.

This Issue

June 5, 2014

A New ‘L’Étranger’

The Refounding Father

-

*

Euny Hong, The Birth of Korean Cool: How One Nation Is Conquering the World Through Pop Culture (Picador, 2014). ↩