Later this year, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York will celebrate its 225th anniversary. Sometimes called the “Mother Court” because it is older than even the US Supreme Court, the Southern District is, with fifty sitting judges, the largest and busiest federal trial court in the country. It has long enjoyed a reputation for excellence that may be almost as great as its judges (of which this writer is one) would like to imagine.

But it was not always so. In its early years, the court, even though encompassing the entire state of New York (its jurisdiction now extends only to the southern counties), was largely limited in its jurisdiction to maritime matters, as well as to minor criminal offenses for which the punishment was “not over thirty stripes.” The business of the court was sufficiently sparse that its first judge, James Duane, did not decide a single case until six months after the court had opened for business.

Although the court’s substantive jurisdiction was not much broadened for the next one hundred years, the great expansion of maritime commerce (the too-often-forgotten engine of much of this nation’s growth) and its increased concentration in the port of New York considerably enlarged the court’s importance. In addition, while most nonmaritime federal cases originated in what were then called the “circuit courts,” the Supreme Court justices who were supposed to “ride” from town to town with the district court judges on these circuits were increasingly conspicuous by their absence, rendering the Southern District judge the effective trial judge of all federal cases in New York City and its immediate environs.

By the time this de facto jurisdiction was made de jure as a result of congressional acts passed between 1891 and 1911, the Southern District Court had already come to be regarded as first among equals so far as federal trial courts were concerned. Doubtless this was largely a function of New York’s prominence as the nation’s financial and commercial center. But the appointment to the court of such luminaries as Learned Hand (appointed in 1909) and his cousin Augustus Hand (appointed in 1914) helped to burnish its reputation.

Which is not to say that the court’s early work may wholly escape criticism. In the pre–Civil War period, for example, the court’s attitude toward slavery was equivocal. As elsewhere in the North, New York’s merchant marine was not above participating in the by-then-illegal slave trade when the profits so tempted, and, while it was in the Southern District that the only death sentence for slave trading was carried out, rather more common were rulings that chose to ignore the evidence of numerous chains and manacles that indicated the likelihood that the “cargo” at issue would have consisted of enchained human beings.

In any event, it was not until the twentieth century that the Southern District Court really came into its own, becoming, in Robert Morgenthau’s words, “generally acknowledged to be the best in the justice business.” A full and serious history of the court remains to be written. But in The Mother Court, James Zirin, a well-respected trial lawyer, deftly illustrates through anecdotes the characteristics that have led to the court’s high repute, including the ingenuity of the lawyers who practice before it and the quality of its judges.

Most of Zirin’s anecdotes are drawn from the years in the 1960s and early 1970s when he was an assistant United States attorney in the Southern District, but they illustrate well the breadth of the court’s caseload as it developed from the 1920s up to the present. Thus, among much else, he chronicles the court’s leadership in protecting free speech against government censorship (ranging from Ulysses to the Pentagon Papers), in prosecuting white-collar offenders long before it was fashionable, in exposing official corruption (not least by corrupt judges), and, most recently, in conducting terrorism trials in accordance with due process and the Constitution.

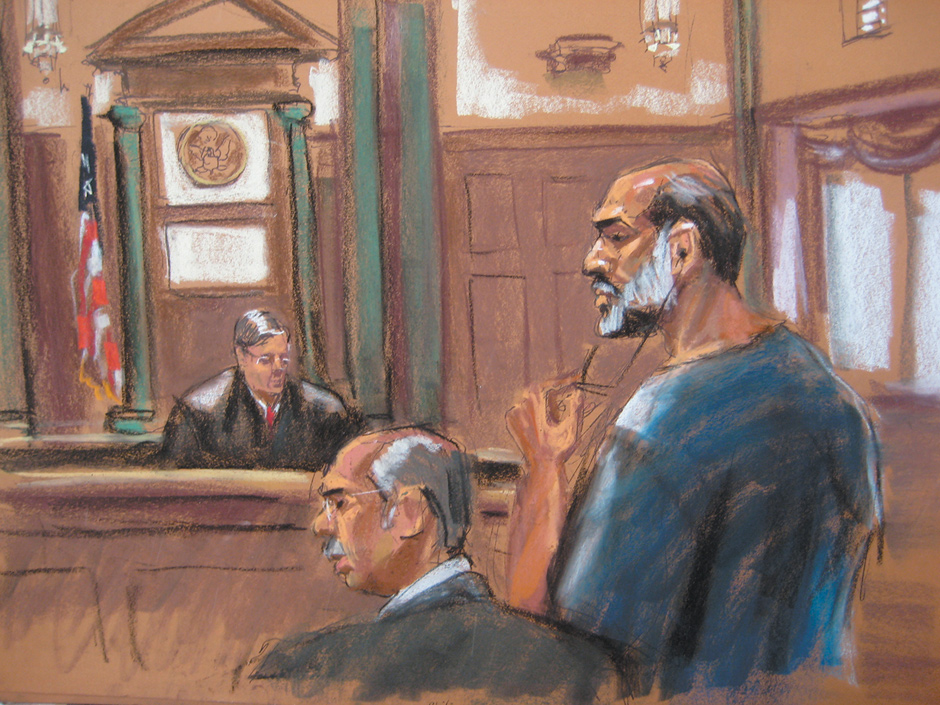

Though too late to be included in Zirin’s book, a comparison between the recent trial in the Southern District Court of Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, Osama bin Laden’s son-in-law, and the extended proceedings before military tribunals in Guantánamo is illustrative: the former was a prompt and straightforward jury trial in a public courtroom conducted by a neutral judge in full compliance with the federal rules of evidence, while the latter proceedings before military commissions are conducted at a snail’s pace in remote locations with limited access and under rules of evidence that permit such extensive hearsay that an accused may never get to confront his accuser. Such rules would not be permitted in the Southern District Court.

Advertisement

Zirin’s fluid prose and eye for detail make The Mother Court fun to read, while faithfully conveying the underlying importance of the issues at stake. Although federal judges are sometimes a bland and stuffy lot, Zirin writes well about the colorful characters who have occasionally graced the Southern District bench. Thomas Murphy, for example, who, after successfully prosecuting Alger Hiss, sat on the Southern District Court from 1951 to 1970, was a tough, even harsh judge, who nevertheless possessed a quick Irish wit that Shaw and Wilde might have envied. Arraigning a Black Muslim defendant on a narcotics charge, Murphy asked, “Do you have a lawyer?” to which the defendant replied, “Allah is my counsel.” “Who,” responded Murphy, “represents you locally?”

Another merit of Zirin’s book is that it does not gloss over some of the more shameful chapters in the court’s modern history, such as the execution of the Rosenbergs. Not sparing criticism of the prosecutors in the case, Irving Saypol and Roy Cohn (whom Zirin calls “twisted”),1 he saves his most scathing remarks for the trial judge, Irving Kaufman, “imperious in nature,” who not only deprived the Rosenbergs of a fair trial but also, in Zirin’s view, grossly exaggerated their crimes in order to try to justify their execution.

To Zirin’s excellent account, the following may be added. Although it is now the general consensus that Julius Rosenberg was guilty of espionage but Ethel Rosenberg was not, this is largely based on evidence developed after their trial, including the subsequent recantation of David Greenglass (Ethel’s brother and the primary witness against her) and the post-glasnost, pre-Putin disclosures of secret Soviet files. Perhaps it should have been obvious to Kaufman, even at the time, that Ethel was at most an accessory to Julius’ spying, hardly deserving the ultimate punishment. But the question this writer would put is: When the real facts of Ethel’s relative innocence later emerged, did Judge Kaufman feel the slightest remorse? Those of us who knew Kaufman would doubt it, for self-doubt was not in his character.

Most federal judges, by contrast, recognize that, despite their best efforts, they will sometimes make mistakes, which they must then do their best to undo. Yet even if Kaufman had felt remorse, what would it have mattered? Execution is the one mistake that can never be even partially rectified. Ethel Rosenberg was neither the first nor the last to be wrongly executed; but a law that permits a wrong to occur than can never be remedied is fundamentally lawless.

Since Zirin’s book is a collection of anecdotes but not analyses, it would be unfair to criticize it for failing to address why the Southern District has come to be viewed as a court of great importance. But an answer to that question may be briefly attempted here, first with respect to federal district courts in general and then to the Southern District in particular.

One must begin with the vast enhancement of federal involvement in everyday affairs during the twentieth century, and the concomitant involvement of the federal courts in overseeing that enhancement. Thus, for example, whereas before the New Deal business disputes were almost exclusively the province of the state courts, the enactment of the federal securities laws in 1933–1934 materially shifted such oversight to the federal courts. Similarly, employment practices, once the exclusive domain of state courts, have, as a result of federal labor laws, minimum wage laws, employment discrimination laws, and much more, become the subject of federal lawsuits at least as often as state lawsuits. More generally, the “limited” jurisdiction of the federal courts now bears on almost every activity that Americans may undertake.

It is also important to remember that the great majority of federal disputes are resolved in the district courts, even though the district courts are the low rung in the federal judicial hierarchy. To be sure, all “final judgments” of the federal district courts—that is, judgments that end the case—are appealable to the federal courts of appeals; but over 90 percent of all federal cases settle or are dropped before final judgment is entered, so it is the district court’s interim rulings—which are mostly unappealable because they do not end the case—that really determine the outcome. For example, securities class actions, which typically allege that management has defrauded shareholders of millions, even billions of dollars, usually begin with the defendants moving to dismiss the lawsuit on various legal grounds. If the motion is granted, the lawsuit is over and the plaintiffs can appeal; but if the motion is denied, no appeal is permitted and the lawsuit goes forward.

The next major step is a motion by the plaintiffs to “certify the class,” i.e., allow the plaintiffs to represent all similarly situated shareholders. Although the district court’s decision on this crucial motion is subject to possible review by the court of appeals, such review is not mandatory and is frequently denied: the theory being that the court of appeals should wait until the rendering of the final verdict after trial when it will have a full evidentiary record to guide its judgment. But in practice, fewer than three in every one thousand class action lawsuits concerning securities actually go to trial, for the stakes are simply too high to take the risk of a somewhat unpredictable jury verdict. And so the case is settled, with the amount of the settlement being pretty much a function of the district court’s rulings on the two preceding motions.

Advertisement

Moreover, even in those cases where a district court’s rulings or final judgments are reviewed on appeal, the great majority of those decisions are affirmed; and only a very tiny fraction of all federal cases ever make it to the Supreme Court. So, for most practical purposes, the federal district court is where the action begins, and ends.

An important corollary of this is that it is the district court that must first grapple with new issues of law, whether they be questions of how to interpret complicated new laws (such as Dodd-Frank) or how to reconcile old laws with changing conditions (such as, for example, applying existing copyright laws to the new conditions of the Internet). Indeed, this confrontation with new ideas of law is part of what makes being a federal district judge such a thrilling, and challenging, job. For while the Supreme Court may (sometimes) have the last word on a new legal issue, the district courts have the first word, and how they choose to approach the issue will typically fix the frame within which other courts consider it.

Thus, for example, in the difficult area of reconciling anti-obscenity laws with First Amendment protections, where the Supreme Court has often offered little more guidance than “I know it when I see it,” it was Southern District judge John Woolsey, in the 1933 case in which the government sought to ban Ulysses, who first enunciated the critical test (later adopted by all higher courts) that any given passage alleged to be obscene must be viewed in the context of the work as a whole in order to determine its meaning, purpose, and legality.

This role of the district court in initiating and framing novel issues of law also begins to explain the importance of the Southern District Court. For with so much commercial and financial wealth, power, and innovation centered in New York, it is not surprising that many of the most important new legal issues arise here. Thus, as Zirin points out, it was Bennett Cerf, of the New York publisher Random House, who purposely provoked the Ulysses prosecution as a test case.

Moreover, just as innovation breeds innovation, so the lawyers in the leading New York firms are accustomed to spotting new issues and offering novel arguments in cases tried in the Southern District; and Southern District judges are similarly accustomed to entertaining such arguments, rather than simply dismissing them as “unprecedented.” As Zirin again notes, it took an advocate as skilled as the well-known literary lawyer Morris Ernst to devise the winning argument in Ulysses, an argument that now seems “obvious” but was then unprecedented. And it took a judge as open-minded as Woolsey to adopt it. (Of course, it is a question of degree. There are many fine federal judges throughout the land who are not afraid to take a fresh look at old problems. It may be ventured, however, that Southern District judges are a bit more likely to do so, because innovation has become one of the court’s traditions.)

More subtle factors are also at work. Most federal district judges are nominated at the recommendation of the state’s most senior senator (provided he is of the president’s party), and New York has a long tradition of senators (e.g., Robert Wagner, Jacob Javits, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Charles Schumer) who have taken this role very seriously. Almost all federal judges in the Southern District practiced in that district before assuming the bench, and therefore are very familiar with the court’s traditions of scholarly opinions and hard work. There is also a tradition among judges in the Southern District of being very demanding of lawyers—of expecting nothing but the best and of being at times downright dismissive of lawyers who offer anything less—and this carries over to how that lawyer acts when he or she becomes a judge.

Nonetheless, proud as I am to be a part of a court with such great traditions of innovation and craftmanship, I think Zirin, who begins his book by calling the Southern District “this greatest of courts,” may overstate the case for its distinctiveness. The more important differences, I think, are those between the federal courts and the state courts and between the federal district courts and the higher federal courts.

As to the first difference, federal judges, being appointed for life, possess an independence that few state judges, who serve for a term of years and are usually subject to popular election, can hope to achieve. The result, obvious to all, is that federal judges can take unpopular stands that few state judges can risk. It is a great testament to the bravery of some state judges that they will nonetheless undertake such risks—although the most recent such decision that comes to mind, the 2003 decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Court legalizing same-sex marriage, was decided by one of the four state courts whose judges are appointed and serve until retirement. But on the whole it has been the federal courts that have repeatedly taken the lead in protecting the rights of unpopular minorities, radicals, and what Clarence Darrow called “the damned.”

This difference is well understood. What, perhaps, is less well understood is the degree to which federal district courts tend to be less ideological than federal appellate courts. To some extent, this is simply a function of being closer to the facts, to the gritty details of a particular case. When, at her Supreme Court confirmation hearing, my former colleague Sonia Sotomayor quoted with approval Benjamin Cardozo’s famous aphorism that “the facts drive the law,” she was immediately attacked by ideologues from the far right and far left who suggested that this meant she was “unprincipled.”

On the contrary, what now Justice Sotomayor plainly meant, and what every trial judge understands, is that the law is, first and foremost, engaged in the resolution of practical disputes, and if the application of a principle of law to the facts of various cases repeatedly leads to resolutions that seem nonsensical, it is probably because there are other, offsetting (but perhaps hitherto hidden) principles that need to be recognized—and have not yet been—in order to arrive at a just and balanced result.

If this seems too abstract, consider that higher federal courts, and perhaps most especially the Supreme Court, spend a lot of their time debating what is the right method for construing a statute: “plain meaning,” “legislative intent,” “statutory purpose,” and whatnot. Such debates, which are frequently argued in highfalutin language about separation of powers, judicial restraint, rule of law, and the like—and that carries over to academic debates (and debates in the pages of this publication) about “formalism,” “textualism,” “originalism,” and “legal positivism,” among others—strike many district judges not only as a disguised conflict about economic and social policies but also, in some cases, as fundamentally misguided even when sincere.

It is as true today as when Harvard law professors Henry M. Hart and Albert M. Sacks first stated it that “the hard truth of the matter is that American courts have no intelligible, generally accepted, and consistently applied theory of statutory interpretation.” This is not because the “correct” rule of statutory interpretation, like a hidden law of physics, is just waiting for some legal genius to discover it. Rather, it is a question of there not being one size that fits all. As another Harvard law professor, Todd Rakoff (my brother), has pointed out, rules of statutory construction are really more like tools, and knowing which tool to use in a given case is a function of the particular problem presented by the particular case.2

Thus, for example, the problem of determining how a statutory copyright provision enacted prior to the growth of the Internet should be applied to an Internet use of copyrighted material is at least in part a function of determining whether the use in question (even though involving a new technology) presents the same kind of issue that Congress was grappling with when it enacted the statement dealing with copyright, in which case the statute can be applied in a fairly straightforward way, or whether the nature of the technology involved in this particular use is so different and transformative from what Congress was considering when it wrote the provision in question that a broader statutory interpretation, looking at overall congressional intent, is appropriate.

Does this mean that the law, one of the functions of which is to provide certainty, will not always be predictably certain? Yes. But every district judge knows, from experience, that that is the way it is and has always been, in this complicated world of ours. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. famously stated, “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.”3

For the judges of the Southern District Court, the “experience” to which Justice Holmes refers includes not only the immense variety of factual situations with which the court is daily confronted but also the historical experience arising from the court’s long record—a record that includes many deliberations over what constitutes justice and fairness in an even more immense variety of circumstances. If, in the daily act of deciding cases, the judges are able to call upon that wealth of experience to arrive at their decisions, they will be true to the traditions of the Mother Court.

-

1

Cohn and Saypol also share in common that, while each was later criminally indicted (Cohn three times), neither was ever convicted. ↩

-

2

See Todd D. Rakoff, “Statutory Interpretation as a Multifarious Enterprise,” Northwestern University Law Review, Vol. 104, No. 4 (2010). ↩

-

3

To which one might add Yogi Berra’s equally apt remark: “It is really hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” ↩