People are amazed or disgusted, or both, at today’s “power of the media.” The punch is in that plural, “media”—the twenty-four-hour flow of intermingled news and opinion not only from print but also from TV channels, radio stations, Twitter, e-mails, and other electronic “feeds.” This storm of information from many sources may make us underestimate the power of the press in the nineteenth century when it had just one medium—the newspaper. That also came at people from many directions—in multiple editions from multiple papers in every big city, from “extras” hawked constantly in the streets, from telegraphed reprints in other papers, from articles put out as pamphlets.

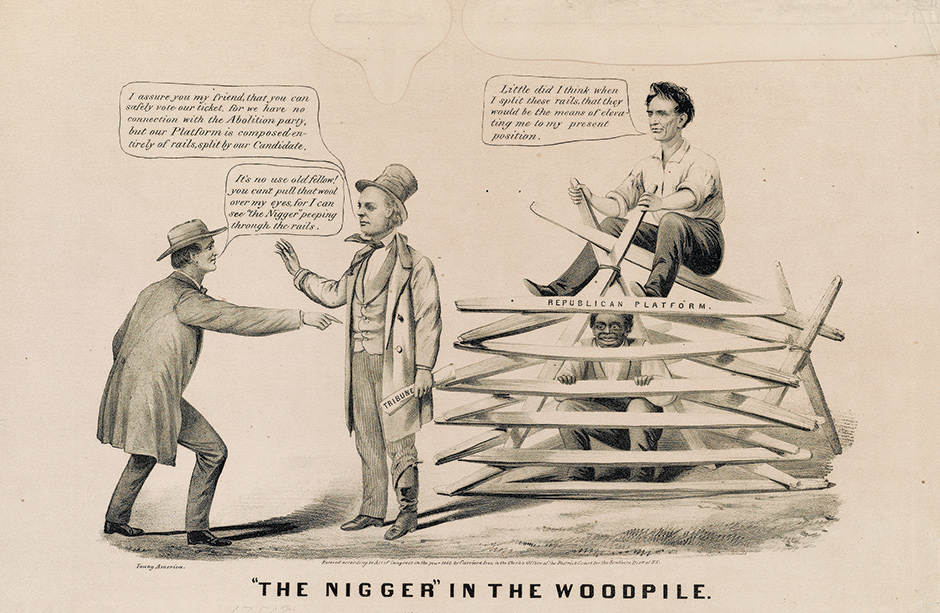

Every bit of that information was blatantly biased in ways that would make today’s Fox News blush. Editors ran their own candidates—in fact they ran for office themselves, and often continued in their post at the paper while holding office. Politicians, knowing this, cultivated their own party’s papers, both the owners and the editors, shared staff with them, released news to them early or exclusively to keep them loyal, rewarded them with state or federal appointments when they won.

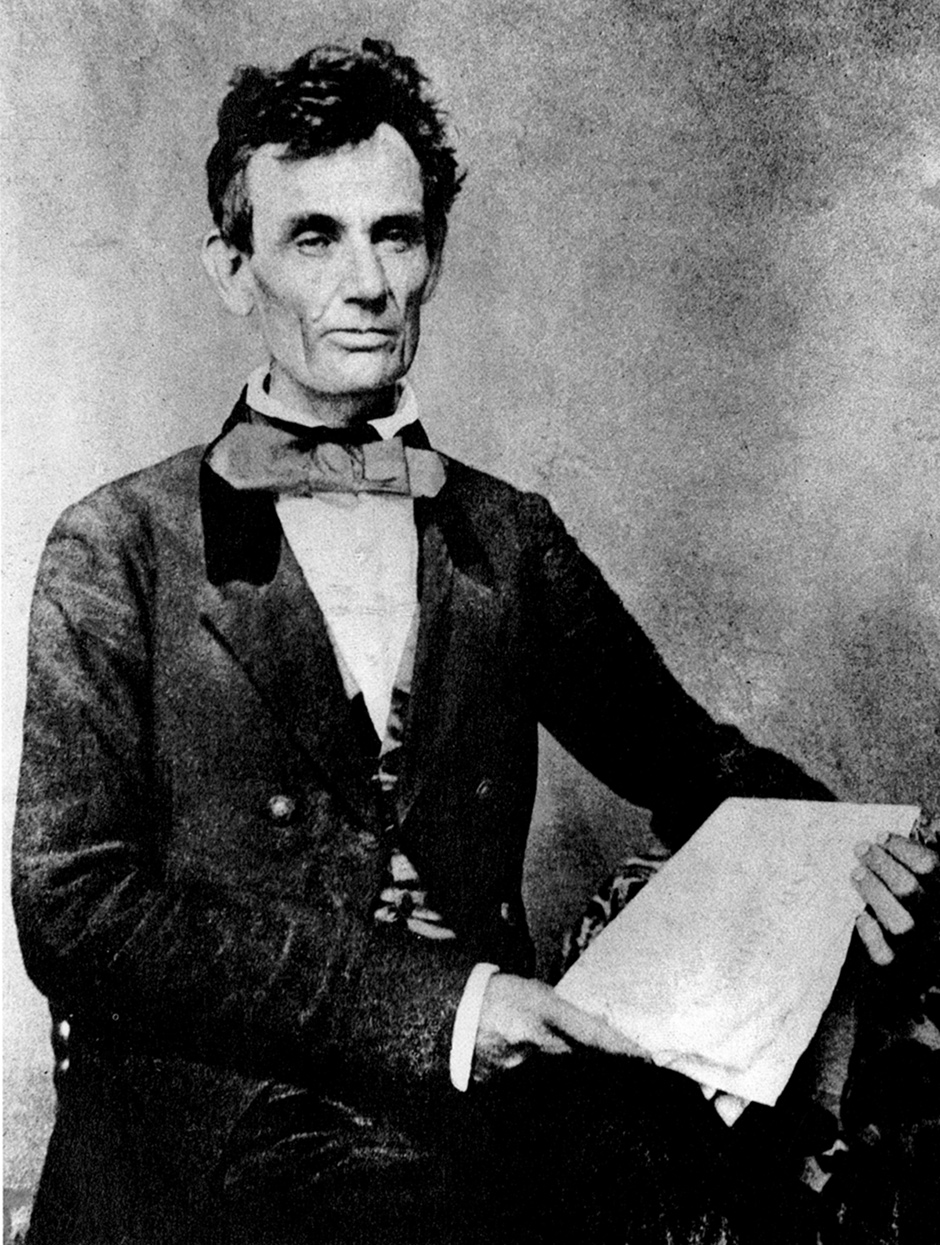

It was a dirty game by later standards, and no one played it better than Abraham Lincoln. He developed new stratagems as he rose from citizen to candidate to officeholder. Without abandoning his old methods, he developed new ones, more effective if no more scrupulous, as he got better himself (and better situated), for controlling what was written about him, his policies, and his adversaries. Harold Holzer, who has been a press advocate for candidates (Bella Abzug, Mario Cuomo) and institutions (the Metropolitan Museum of Art and various Lincoln organizations), knows the publicity game from the inside, and he is awed by Lincoln’s skills as a self-publicist, that necessary trait of his time. Holzer is also a respected and influential Lincoln scholar who does not come to bury Lincoln with this new information but to wonder how a man could swim so well through the sewer and come out (relatively) clean.

Lincoln’s arena broadened as he climbed the ladder of power. He went from local venues in his own state—rival papers in Springfield and Chicago—to the newspaper power center in New York, with three main papers and the pioneering syndicate the Associated Press. Then, in Washington, he had to deal with the concentration there of many papers’ bureaus. He developed different skills for each widening stage of his career. In roughly chronological but overlapping order, there were five main stages.

1. Infiltrating

Lincoln early followed the axiom, If you can’t lick ’em, join ’em. As a beginner with no party standing, he lacked the common coin of exchange in the political and journalistic worlds, patronage. A member of the Whig Party, he got into the game the one way he could—by writing anonymous articles for Whig papers to promote him or his friends and to denigrate rivals. This could be dangerous in that era when caning or horsewhipping editors or reporters was common. Horace Greeley, the famous abolitionist editor of the New York Tribune, was pummeled by a congressman on a street outside the Capitol in Washington. The editor of Lincoln’s local paper, the Sangamo Journal, was beaten up several times—once by a furious preacher and once by no less a figure than Stephen Douglas. They got off lightly by comparison with a Massachusetts editor (of the Essex County Democrat), who was drawn around town tarred and feathered for what he published. Lincoln had to know that his own rancorous articles (and those of his ally and law partner William Herndon) could be dangerous for them, as well as embarrassing, if they were found to be the writers.

On one occasion, in 1841, that happened—and it involved not only Lincoln but his fiancée Mary Todd. The two had collaborated on a series of scurrilous letters from a fictitious “Rebecca” that vilified James Shields, a rising candidate in the Democratic Party (he would later be elected a senator three times from three different states). The fake Rebecca, who claimed Shields was a former beau, mocked his Irish origin and declared him “a fool as well as a liar…. With him truth is out of the question, and as for getting a good bright passable lie out of him, you might as well try to strike fire from a cake of tallow.”

Shields stormed into the office of the Sangamo Journal, demanding that the editor, Simeon Francis, tell him who was behind the Rebecca letters. When Francis asked Lincoln what he should do, Lincoln, in order to shield his Mary, took sole responsibility (without admitting he wrote anything). Shields challenged him to a duel, and they actually met on the dueling ground—but Lincoln, as the one receiving the challenge, had the right to choice of weapons. When he called for broadswords, this gave him, with his long and strong right arm, a ludicrous advantage, and the fight was called off. Though Mary liked to recollect how her own beau had stood up for her, Lincoln cut off any later attempts to remember this episode—perhaps (though Holzer does not mention this) because Shields, vilified by “Rebecca,” became a Union officer when Lincoln was president, and was wounded at the Battle of Kernstown. There was a real duel after all.

Advertisement

Though Lincoln became more circumspect about his own anonymous writings, he continued to have his secretary John Hay write secretly for the cause when he was president, and Mary leaked her own items to the press from the White House—once almost disastrously when her favorite reporter released to a New York paper Lincoln’s annual address before it was delivered. Lincoln himself, even as president, continued to ghostwrite items for the Philadelphia Press, a paper he liked.

2. Co-opting

When Lincoln did not get enough of his way with anonymous writings in other people’s papers, he helped set up his own. He was a principal backer of the Old Soldier, begun to support the 1840 Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison. The paper promised to “sear the eye-balls, and stun the ears” of any Harrison detractor. Holzer says it is typical of the time that Lincoln’s once and future foe, Stephen Douglas, founded an opposing paper, Old Hickory, for the Democratic candidate, Martin Van Buren. Douglas, Holzer writes, “saw no conflict in playing the concurrent roles of editor, letter writer, advocate, and of course, political leader.” Lincoln would be just as crass, without the same clout at this stage. Both campaign papers died after the election (which Lincoln’s candidate won), but Lincoln was playing a longer game in 1859, as he began his maneuvering for the White House. Aware of the importance of the German vote, he secretly financed a paper, the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, with what Holzer calls an “iron-clad clause” that the paper will never “depart from the Philadelphia and Illinois Republican platforms.” Lincoln had bought himself a paper with guaranteed compliance.

The year before that purchase, he had found a way to be a self-publisher. Knowing that his direct senatorial bid against Douglas would be widely reported, he pestered the better-known and incumbent Douglas into meeting him in a series of debates. It was clear that Douglas’s home paper, the Chicago Times, would give the meetings heavy coverage, so Lincoln collaborated with the Chicago Tribune to have its own scribe, Robert R. Hitt, make a record that favored him. Lincoln tried to delay the opening of one debate till his stenographer got to the platform, saying “Ain’t Hitt here? Where is he?” Though Douglas won the Senate seat that year, Lincoln knew he had come off well in the debates, which were given lengthy transcription in the newspapers (a complete one in Horace Greeley’s important New York Tribune).

Not content with the “real time” reporting of the event, Lincoln made up a scrapbook of the newspaper accounts, letting Douglas’s side appear in the Chicago Times version, but making sure his side was reproduced from the Chicago Tribune. Then he worked to have the “scrapbook” published, which became a hit, selling 30,000 copies—Holzer calls it “the most brilliant publishing venture Lincoln ever initiated.” He used the fame of the debates to arrange for a New York lecture—what became the Cooper Union address—that was heavily covered in the all-important New York newspapers, which Lincoln had cultivated for years and would stay close to from this point on.

Greeley’s New York Tribune erratically, and Henry Raymond’s New York Times fairly steadily, favored Lincoln as president. Even the editor of the racy (and racist) New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett, was worth cultivating in Lincoln’s eyes. He hoped to gain at least occasional neutrality in this tainted forum, and it paid off when Bennett allowed the young reporter Henry Villard to report favorably on Lincoln’s long wait between his election and inauguration. Lincoln could usually charm a reporter, when given enough time with him.

3. Buying Off

As soon as Lincoln was elected he set about new dealings with the press. His inaugural address was secretly set in type by the editor of the Illinois State Journal, which had the sole firsthand report of his remarks at the train station as he left for Washington. Armed with the presidency, Lincoln famously tried to appoint cabinet members and military officers of as wide political variety as would cooperate with him. Holzer shows us something further—that he used patronage to recruit the loyalties of newspaper owners, editors, and reporters on a grand scale. Newspapering became the preferred path to becoming ambassador, port inspector, revenue collector, postmaster, and White House staffer—dozens and dozens of the ink-stained were brought in to save the Union.

Advertisement

Lincoln even kept wooing the stubbornly negrophobe editor James Gordon Bennett, of the New York Herald, making his son a navy lieutenant (how could the father not support a war his favored son was fighting in?). Lincoln helped a favored editor, John Wein Forney, move from the Philadelphia Press to set up the Sunday Morning Chronicle in Washington by securing for him the remunerative post of secretary of the Senate and giving the new paper government advertising accounts.

Lincoln kept doling out measured favors and refusals to the papers as events made for shifts in the situation. The volatile Horace Greeley, for peace one day, for abolition the next, was especially exasperating. The man was too respected to ignore, and too flighty to be relied on. With all his other tasks and distractions, Lincoln could never take his eyes from a range of competitive papers. The job got increasingly difficult as the reports of war correspondents flooded into their respective papers. Some of Lincoln’s generals, especially William Tecumseh Sherman, hated reporters anywhere near them or their operations, and Lincoln had to hear editors complaining of those reporters’ treatment. On the other hand, some generals (like George B. McClellan and John C. Fremont) cultivated the press in ways that slighted Lincoln. So different degrees of latitude and stricture had to be constantly calibrated.

4. Repressing

The power of the press is always a two-edged sword. It can wound even its user. As Lincoln had to restrict other liberties in time of war, he meant to blunt or cripple papers that made his job more difficult (it often seemed, after all, not a difficult task but an impossible one). Holzer describes Lincoln’s repression as mostly a hidden-hand activity. It began with generals either crushing rebel papers in areas they controlled, or silencing Northern reporters telling too much about troop dispositions or movements. Lincoln did not want to hobble generals so long as they were doing their job, and he tried to stay out of the scuffles with journalists on the battlefield. But many government departments joined in actions to restrict or censor news gathering—the telegraph company, the Post Office, the Treasury, the War Department, as well as some local courts. All exercised some form of censorship, especially after bad news flooded out from the disastrous early defeat of Union forces at Bull Run. Lincoln generally just let this censorship happen, without taking the blame.

Journalists who tried to break the censorship could end up detained with other war prisoners at Fort Lafayette, which became known as the “American Bastille.” Some refractory newsmen were imprisoned at Fort McHenry. On the other hand, Lincoln let it be known that there should be a relaxation of the repression as his reelection campaign approached. One of the few times when he did voice his support for control of the press was after his old nemesis the Chicago Times was suppressed by General Ambrose Burnside.

Burnside had also shut down the New York World and arrested for treason Clement Vallandigham, who was opposing the war. These actions caused a protest meeting of editors in Albany, to which Lincoln felt he had to reply. Without undermining Burnside’s authority, Lincoln reopened the Chicago Times, and freed Vallandigham from prison, to be deported to the Confederacy (giving it the onus of imprisoning him as an independent Northerner). He wrote a letter to a signatory of the Albany protest, Erastus Corning, justifying his executive authority in war.

5. Outmaneuvering

The Corning letter is an example of what Holzer calls one of Lincoln’s most ingenious inventions for dealing with the press. Rather than make a speech or a presidential proclamation of some sort, or answer a single newspaper, he sent private letters, knowing they would be published broadly. He even leaked his most famous letter—that to Horace Greeley on his “paramount object” in the war (to save the Union)—to one of Greeley’s rival papers, the Washington National Intelligencer. In that way, each paper that had a copy of the letter could publish it without treating it as any one outlet’s property. Lincoln was often playing one move ahead of the game in this way. When Greeley urged Lincoln to hold a peace conference in Washington, Lincoln suggested it would be better conducted in a neutral place, on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, under Greeley’s own management, thus shunting delegates off to an exercise in futility for which Greeley would carry the sole responsibility. Lincoln was a hard man to trap.

When he was in a position to play the papers off against each other and bypass them with his leaked letters, Holzer maintains, Lincoln

revolutionized the art of presidential communications…. [He] had come to realize that he could control “public sentiment” best by bypassing the editors and going directly to their readers. Rather than resume making time-consuming public speeches, he transformed the so-called public letter into a weapon of mass communication.

It is no wonder more recent presidents have tried to go directly to the public over the heads of the mass communicators. But the public is now far more splintered and babbling with its own thousand voices. Lincoln had only one medium to circumvent, the newspaper. More recent officeholders are joining a Babel of self-publicists.

This is not the only thing that makes Lincoln’s situation different from the modern one. Lincoln had one war to deal with. Now we have many fronts in our omnidirectional war with terrorisms, foreign and domestic. But the greatest difference may be in the character of the president himself. Lincoln was not only shrewd, innovative, and imaginative. He continued dealing with people—editors, generals, politicians—who had been personally insulting to him, as well as destructive in their performance during a war. He did not let amour propre get in the way of what he was trying to accomplish. He had an inner confidence that could absorb obloquy and dishonesty and viciousness without letting them jostle him off his concentration on what he felt was America’s calling as well as his own. No wonder Holzer thinks he came out of the sewer clean.

In order to demonstrate the thorny particularities of Lincoln’s dealings with the press, Holzer gives us vivid biographical glimpses of the willful and colorful editors who fought for Lincoln’s attention—the “Big Three” in New York (Greeley, Raymond, and Bennett)—along with other editors there: Manton Marble (New York World), James Watson Webb (New York Courier), William Cullen Bryant (New York Evening Post), Henry Ward Beecher (New York Independent). In Illinois, there were Joseph Medill and Horace White (Chicago Tribune), James W. Sheahan (Chicago Times), Charles Lanphier (Illinois State Register). These and other editors, along with their pushy reporters, are an important (if vicious) part of the history of American journalism. Holzer has done exhaustive research into their respective journals, and he usefully adds an epilogue on what happened to the leading journalists after the war. Only by showing us what Lincoln was up against can Holzer measure the man’s achievement in using, controlling, or defying the one news medium of the time, the newspaper.