Muriel Spark converted to Catholicism in 1954 and published her first novel to critical acclaim three years later. She was thirty-nine. She always insisted that the book could not have been written without her conversion. Catholicism had enabled her to write. It is hard to imagine another novelist, however devout, making this claim. So what is going on here and what does this tell us about one of the most eccentric yet consistent bodies of postwar fiction by any British writer?

In The Bachelors (1960) the Catholic Matthew has invited Elsie to dinner with amorous intentions, but the idea of falling into a state of sin makes it hard for him to follow through with his project. Cutting up an onion for the meal, he decides that if he eats it raw the girl will be so put off by his breath that there will be no danger of sinning. Then he is cheered, or tempted, by the thought that this is his last onion, hence absolutely necessary for the meal, a circumstance that seems to legitimize his opening himself to sin. But is it really the last onion? If there is another “miraculous onion” in the vegetable box, this will be a sign that he should eat it to stay pure.

In the event there is one “small shrivelled onion nestled in the earthy corner among the remaining potatoes.” Surely not “big enough for the supper,” Matthew reflects. He considers eating the small onion, but fears it will not be sufficient to put a girl off, then, thinking “lustfully of Elsie,” eats the large onion instead. As it turns out Elsie’s previous boyfriend was a great eater of raw onions. She is not put off at all and the two end up in bed.

Described like this, the episode seems a tongue-in-cheek comedy of moral conscience. But beneath the competition between sin and purity another struggle is being played out. Matthew seems less concerned by any real wrong he might be doing by seducing his dinner guest than by the idea that his sexual inclinations are a sign of “weakness.” By making love to a woman, he will lose that absolute control over his life that all the bachelors of The Bachelors seek. In this regard a large onion is “a mighty fortress,” a source of strength, while, comparing the two onions, it is hard not to feel that the shriveled specimen nestling between potatoes is an impotent organ. Matthew “seizes” the bigger “peeled onion” and eats it “like a man,” in order not to have sex. Virility lies in controlling one’s own urges, in the victory over oneself.

From beginning to end Spark’s work is shot through with these tensions. Whether it is a matter of controlling one’s weight, being disciplined about work, ending a relationship, resisting a con man, or simply persuading others rather than being persuaded by them, the question of control and loss of control, or more simply winning and losing, is always to the fore. Her novels are full of ingenious frauds and manipulators on the one hand and ingenuous victims ever ready to succumb to them on the other. In The Bachelors a spiritualist medium is taking everybody for a ride. In The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1960) a man employed as a consultant on absenteeism ruthlessly manipulates both employers and staff of the two companies he works for. In Loitering with Intent (1981) an aristocrat and publisher seeks to control the lives of prominent men and women by inviting them to publish confessional autobiographies, then blackmailing them.

But aside from the larger trajectory of the plot, almost every encounter, every relationship is a struggle to assert power, something that often leads the more sensitive characters toward mental breakdown. In Spark’s first novel, The Comforters (1957), Caroline imagines that her whole life is being manipulated by hidden observers who are writing a novel about her. She hears voices, the sound of a typewriter. This paranoid delusion (based on hallucinations Spark herself had suffered while taking the slimming drug Dexedrine), though apparently a weakness, provides her with a weapon for manipulating her boyfriend, Laurence: she will not do as he wishes when to do so would satisfy predictions announced by the novel-writing voices. But Caroline’s newly found Catholicism is also a tool of manipulation. Having accepted a higher value than romantic love, she can now deny Laurence sex without ending the relationship. She can call all the shots and still present herself as “good.” “I love God better than you,” she tells him.

To dominate with success, then, one must be able to believe that one is not morally in the wrong, since this might cause anxiety and attract opposition. Likewise, it is good to have rules that prevent your behaving too ruthlessly, since if you start destroying the people around you—and Spark’s characters are often disturbingly willing to cause another’s death—society will ultimately exclude and imprison you; at the very least you will lose the antagonist whose weakness guarantees the dominance you enjoy. In this regard Catholicism offers both a tool and a brake in the struggle for power. Competing with others one nevertheless (Spark claims she became a Catholic on this “nevertheless principle”) bows down to a strict moral code and a religious practice that cannot be questioned. One also acknowledges the triviality of earthly aspirations beside the all-important truth of our mortality and afterlife in an unknowable eternity beyond. Again and again Spark’s characters find their scheming unsettled by reminders of death. In Memento Mori (1959) the plot revolves around a series of anonymous phone calls inviting the novel’s geriatric but always embattled characters to “remember you must die.”

Advertisement

In general, Spark makes ample use of prolepsis in her novels with frequent flashes forward to the deaths of her characters that give a sense of the futility of their various machinations. The author’s total control of her material is thus emphasized, often with great irony and comedy, but at the same time contained and legitimized in a project of Catholic admonition. Of her decision to start writing novels, Spark remarks that “before I could square it with my literary conscience…I had to work out the novel-writing process peculiar to myself, and moreover, perform this act within the very novel I proposed to write.”

The Driver’s Seat (1970) performs that process and brings all these elements together in a schematic tour de force. Lise, who terrorizes others at the office where she works, whose straight-lipped mouth “could cancel them all out completely,” takes a rare holiday. From the opening pages we learn that she will be killed the first night. Capricious and excitable during her flight and on arrival in Italy, she offends and bewilders everyone she meets, rejecting all attempts to seduce and control her, alternately playing the victim, the flirt, or the generous companion in order to break down and dominate everyone who crosses her path. Apparently on the lookout for a man, she eventually finds a reformed sexual offender and persuades him, against his will, to kill her. Handing him a knife and telling him exactly how to cut her throat, Lise thus controls the one event that is normally understood to lie beyond control. Beside a story like this, the decision to set limits for oneself by recognizing the authority of the Catholic Church seems a rather benign if always “conflicted” solution.

Where did this unhappy vision of life come from? Born in Edinburgh in 1918, Muriel Camberg was the first child of a working-class Jewish father and Presbyterian mother. Her Catholicism, then, would be very much a matter of setting herself apart, or joining a cultural elite that included Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh. In The Informed Air, a posthumous collection of essays, she remarks of her humble Edinburgh origins:

The influence of a place varies according to the individual. I imbibed, through no particular mentor, but just by breathing the informed air of the place, its haughty and remote anarchism.

This hardly tells us much and in general, in both her autobiography Curriculum Vitae and the essays in The Informed Air that touch on her life, Spark tells us little about her early or intimate relationships, as if to do so might place a weapon in our hands. Curriculum Vitae opens with lavishly detailed accounts of Edinburgh, what was eaten, how it was prepared, shops, prices, children’s games, and so on. Observation is always a cause of pride and an instrument of control in Spark’s novels (of Laurence in The Comforters we hear that “he is so observant it’s terrifying”).

However, in a rare moment of unguardedness Spark does admit:

We often laughed at others in our house, and I picked up the craft of being polite while people were present and laughing later if there was anything to laugh about, or criticizing later if there was anything to deplore.

Mockery is in fact a constant for Spark’s characters, who are forever putting each other down and, arguably, are themselves collectively put down by the writer with the amused connivance of the reader. Here in The Comforters is the “psychological thug” Mrs. Hogg exchanging words with Louisa, Laurence’s charming and ambiguous grandmother:

“I learn,” said Mrs Hogg, “that you call me a poisonous woman.”

“One is always learning,” Louisa said….

“Do you not think it is time for you,” said Mrs Hogg, “to take a reckoning of your sins and prepare for your death?”

“You spoke like that to my husband,” said Louisa. “His death was a misery to him through your interference.”

Of his grandmother’s improbable relationship with a group of jewel smugglers, Laurence remarks, “We don’t know who’s in whose hands, really.” This question of who is manipulating, or just mocking, whom provides the dramatic core of all Spark’s narratives. Speaking in her biography of her childhood encounter with the charismatic schoolteacher Christina Kay, she remarks: “I fell into Miss Kay’s hands at the age of eleven. It might well be said that she fell into my hands.” Thirty-three years later Christina Kay would be transformed into Jean Brodie in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), the novel that made Spark’s name and fortune. At this point Christina was very much in Muriel’s hands, as indeed is the reader.

Advertisement

A word needs to be said here about the trajectory of Spark’s writing career. A precocious poet at school, her talent recognized by among others Christina Kay, at nineteen Muriel Camberg married the thirty-two-year-old math teacher Sydney Spark, who took her to Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia. Perhaps “he had a hypnotic effect on people,” she says in Curriculum Vitae, unable or unwilling to account for this decision. Certainly there is no mention of love. Perhaps Sydney’s offer of a household with servants and the leisure to write was persuasive. However, by the time she gave birth to a son a year later her husband was behaving in an unhinged and domineering fashion and all too soon she would be demanding a divorce. “If my husband had not been an object of pity,” she remarks, “I would have been much tougher.”

Compassion in Spark’s narratives almost always emerges as a weakness and certainly little is shown to the characters in her novels, whether the compulsive manipulators or their all too willing victims. One must look after oneself. An essay in The Informed Air argues against arousing compassion in novels since this allows readers to “feel that their moral responsibilities are sufficiently fulfilled by the emotions they have been induced to feel.” Satire and ridicule are more effective tools of correction, she suggests, though reading Spark’s stories it never seems that she requires a moral purpose to engage in mockery. It comes naturally enough.

Returning to England in 1944, Spark left her son first with nuns in Rhodesia and later with her parents in Edinburgh. She would never again marry; future boyfriends would soon become sworn enemies. It is on the next thirteen years of her early maturity up to the publication of her first novel in 1957 that most of Curriculum Vitae and the autobiographical essays focus. This was a period when she held minor posts in various publishing houses and was briefly head of the Poetry Society, a position in which she rapidly accumulated enemies.

The theme is always the same: Spark’s struggle to emerge, the depth of her poverty and strength of her commitment, the resistance of the obtuse English upper classes, the eventual triumph of her brilliance, and, above all, the universal recognition it brought her. In an essay, “The Writing Life,” she tells us:

The majority of those one-time [rejected manuscripts] have become a part of my oeuvre, studied in universities…. I was really hungry and undernourished in those days…. Graham Greene, who admired my stories, heard of my difficulties through my ex-companion; he voluntarily sent me a monthly cheque with some bottles of wine for two years to enable me to write without economic stress…. I was now, also, Evelyn Waugh’s favourite author, since The Comforters touched on a subject, hallucinations, which he himself was working on in his novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold; he was generous enough to write a review of my novel in the Spectator, in which he said that I had handled the subject better than he had done.

Curriculum Vitae records personal praise from T.S. Eliot and various other famous names as well as including ferocious attacks on those people Spark felt stood in her way, all invariably dismissed as contemptible and misogynist. In short, even in essays written as late as 2001, Spark constantly feels the need to insist on her achievements, her winner’s status, and though this is hardly attractive it does help us understand the complex relation between form and content in her creative work.

However grim the picture of human relations that emerges from her stories, the manner of their telling is always sparkling, terse, formally brilliant, determinedly cheerful. Spark as author will never appear downcast or deny us her wit and entertainment. We will not come away depressed. Our intellect will be wonderfully stimulated with complex metafictional games that constantly alert us to the writer’s manipulative powers.

Again we have “the nevertheless principle”: society is a grim free-for-all, life chaotic and dangerous, nevertheless I am on top of it and laughing. Loitering with Intent, an autobiographical fantasy in which a young woman outwits a ruthless manipulator to publish a successful first novel that itself manipulates the stories of those seeking to control her, ends with the sentence: “And so, having entered the fullness of my years, from there by the grace of God I go on my way rejoicing.”

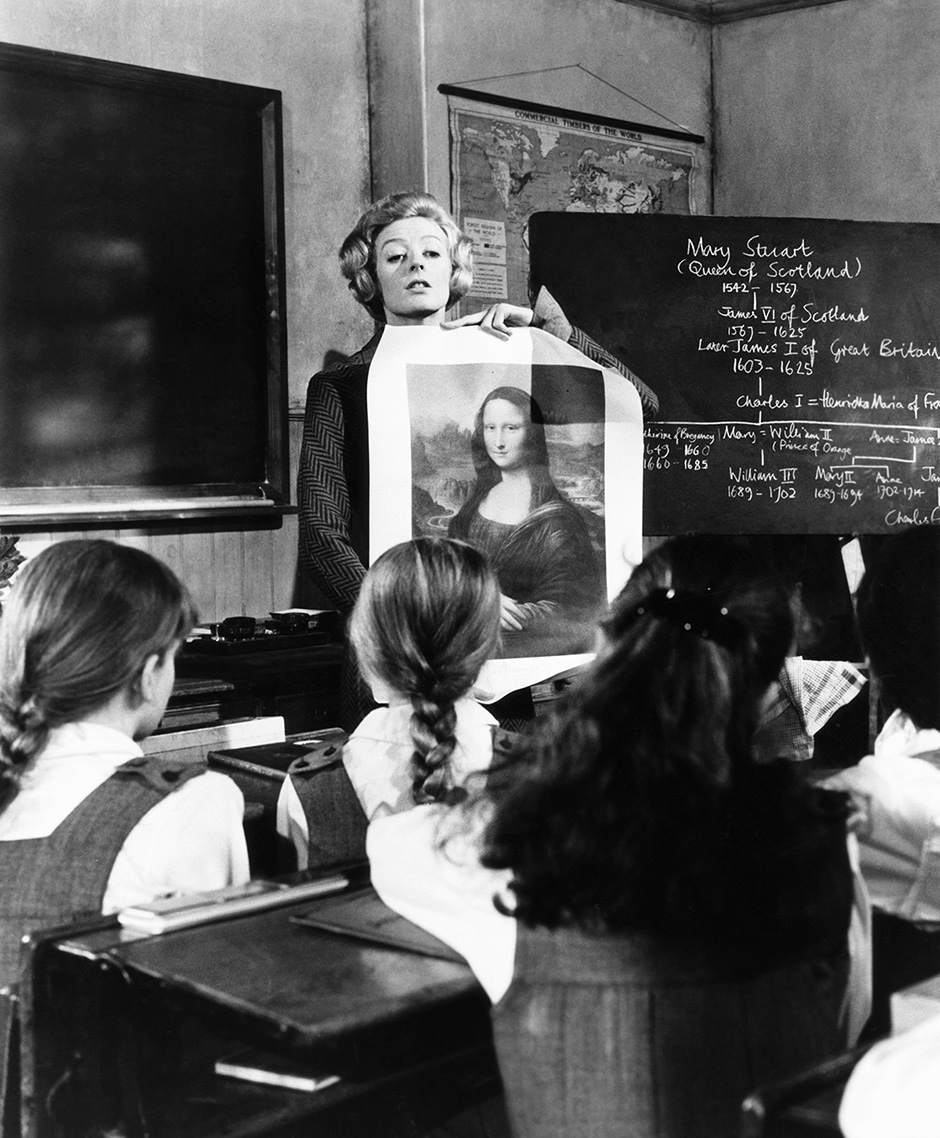

Never is this surface brilliance and cheerfulness more evident than in her sixth novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. In the Edinburgh of Spark’s 1930s adolescence the charismatic schoolmistress Jean Brodie uses unconventional teaching methods and immense energy to take over the lives of a group of girls, the Brodie set, simultaneously befriending and bullying them, dazzling with wonderfully peremptory precepts—“Where there is no vision…the people perish”—intriguing them with details of her love life, and seducing them with the notion that they are becoming a superior “crème de la crème” amid the sour milk of other envious students and teachers.

In particular, having stepped back from a relationship with the school’s married art teacher, whom she supposedly loves, Brodie has an ongoing affair with the younger music teacher, to whom, however, she will not commit herself entirely. She will not marry him. That would be a weakness. At the same time she seeks to have one of the girls become the art teacher’s lover in her place. Needless to say, for all her brilliance and the immense energy of her “prime,” events finally overwhelm and destroy her. One of her girls will betray her, suggesting to a hostile headmistress that Brodie could be dismissed from the school on the grounds of her enthusiasm for Mussolini and Fascism; having lost her position and with it her power, Miss Brodie’s decline and eventual death, all foreseen early on, will be rapid.

Of the Brodie set, the girl who betrays, Sandy, is the one most enthralled by her teacher, most intelligent, and for that reason most in need of freeing herself. Almost at once she begins writing imagined love letters between Brodie and her old boyfriend to savor and take over, at least in her head, the life that has taken over her own. Writing is a tool of resistance and affirmation. Years later Sandy is appalled by the realization that Miss Brodie “thinks she is Providence…she thinks she is the God of Calvin, she sees the beginning and the end.” Hence her decision to “put a stop to Miss Brodie,” as she tells the headmistress.

After which, having vanquished her mentor and antagonist, Sandy retreats to a convent, becoming a cloistered nun and writing a book of psychology that makes her famous. Visited by old school friends and new admirers of her writing, she clutches the bars of the grille through which they speak to her, still entirely torn between the earthly ambition she learned from Miss Brodie and the ambition to curb that ambition she has learned from Catholicism. It is the same conflict that had Matthew choosing between onion-eating and sex in The Bachelors.

Following The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’s enormous success, Spark also withdrew from the scene of her earlier struggles, not to a convent, but first to New York, then Rome, where she enjoyed life among the rich and famous, even buying a racehorse from the Queen in caricature confirmation of her concern with competition and victory. But the high point of her career was already behind her. Success seemed to take the edge off her talent, perhaps because it was the visibility she had been fighting for, not the work in itself, and when the later writing does convince it is always when returning to the London of her earlier poverty, in Loitering with Intent and A Far Cry from Kensington (1988) in particular, the latter galvanized by the revenge Spark is taking on her old boyfriend Derek Stanford, who had published what she felt was an unflattering and largely incorrect biography of her. In this case the plot turns on the moment when the kindly and overweight young widow, Mrs. Hawkins, can suddenly put up with the pushy would-be writer Hector Bartlett (Stanford) no more and denounces him as a “pisseur de copie,” a hack, thus beginning a battle that will lead to her taking control of her weight, changing jobs, refusing to play dogsbody, finding herself a boyfriend, and generally becoming a winner rather than a loser.

More ambitiously still, The Only Problem (1984) has a scholar contemplating a book on the sufferings of Job, something Spark herself had considered in the bad old days of her own sufferings. In Curriculum Vitae she quotes her fellow novelist Tony Strachan as telling her, “No one has ever been as poor as you were in those days. I mean someone of education, culture and background.” The Informed Air also has essays on Job, with Spark characteristically concentrating on the contest of wills between Job and his “comforters,” who insist that his suffering must be a punishment for sin.

Turning from the novels to the essays, one is struck by a continuity of tone. Spark is always emphatic, peremptory, authoritative. “I wouldn’t touch the Bible if it wasn’t interesting in historical, literary, and other ways besides its content,” she tells us. Sometimes the voice is alarmingly close to Jean Brodie’s (“Art and religion first; lastly science. That is the order of the great subjects of life”). Or indeed Mrs. Hawkins’s in A Far Cry from Kensington (“It is my advice to any woman getting married to start, not as you mean to go on, but worse, tougher”). Her many put-downs are always splendid: “of course” Gone with the Wind “is bad art,” she tells us, “but you cannot say fairer than that it is, like our Albert Memorial, impressive.” Or again: “Mrs Gaskell possessed an interesting minor talent. She wrote badly most of the time. In spite of her social zeal it is impossible to take her altogether seriously.”

Ranging from 1950 to 2003 (she died in 2006), the essays of The Informed Air are organized not chronologically but according to subject, an arrangement made possible by the fact that Spark’s voice and opinions show no change over the years. However, while the essays about writing are embarrassingly but always energetically focused on her own success, a number of travel pieces seem limp and mechanical by comparison, as if the author were doing little more than fulfilling a commission. Only the appraisals of other writers really hold the attention. Mary Shelley, Spark tells us, writes about a man whose fabulous ambition creates a monster that reduces him to “a weak, vacillating figure.” Spark clearly sees the affinity with her own themes. “Was Mary Shelley’s life a failure, then?” she asks, reflecting on how little she produced and few friends she had. It is hard to imagine other critics putting this question. “She would have denied this,” Spark immediately reassures herself.

An essay on the Brontës reverses the normal sympathetic portrayal of them as geniuses condemned to wasting their talents teaching the dull children of the rich, imagining instead what hell it must have been to be tutored by the likes of Charlotte. “Genius,” Spark concludes, “if thwarted, resolves itself in an infinite capacity for inflicting trouble.” Heathcliff is an example: a “moral hypnotist…able to manoeuvre his victims.” Again we are in Sparkian territory.

But she saves her greatest enthusiasm for Georges Simenon. His extraordinarily prolific output, his frank admission that he wrote for money, his complete control over his art and “formidable” self-discipline all attract Spark’s approval; even the fact that he dominated a love triangle for many years and that his daughter, “trapped by her hopeless love for her father,” committed suicide seem part of her admiration. Simenon was “phenomenal.” “He had a Catholic education,” she tells us.