Wishful thinking is entwined with gardening. We plant, we dream, we fantasize about flowers, and we see behind them the people who once gave them to us or first showed us their beauty, and then others to whom we showed them and gave them lovingly all over again. Reality then intervenes, a drought, insects, or an intruding wild pig. Gardeners are great killers in pursuit of their dreams. Vita Sackville-West, the genius of Sissinghurst Castle, used to say that her gardening was rivaled only by infant mortality in the Middle Ages. Still we dream on, propelling our gardens and their art into the next season and the next transformation, with visions of our own fresh melons or white-scented flowers on a capricious Cardiocrinum from the Himalayas.

Garden designers are still taught to draw and, all too often nowadays, to plan “sustainably.” They ought to be taught to read more widely. The more we read, the more we see beyond mere “plant material” or “native wildflower areas.” Literature enriches a gardener’s fancy, as Sissinghurst’s garden itself exemplifies, growing from its creator’s romantic love of poetry, French high culture, and Iran (“Persia”) as much as from manure and careful mulching. More poetry and mythology have been spun around flowers than around anything else except women.

The books under review testify to this fantasizing, without always addressing it directly. Several of them exemplify it by being beautifully produced, as if a book on flowers and gardens has to be especially seductive in a way that a book on, say, horses or dogs does not. Carolyn Fry’s The Plant Hunters even contains page-sized envelopes that open to present us with individual prints and reproductions. Public librarians will fear for the shelf life of these eminently removable extras.

In the best of the group, Martyn Rix acutely observes that “though we have fewer botanists, we have more botanical artists than ever before.” These artists are today’s close observers of flowers and fruits, now that “plant scientists” have moved inward to study cells and genes. Most plant scientists are ignorant about gardening. Artists do more for susceptible gardeners’ fantasies. Electronic reproduction is reaching ever higher standards and before long, we will be able to gaze in the winter months on our own images of the world’s finest flower paintings without too much loss of their depth and texture. Botanical artists often aim to be exact, scientific, and even analytic, but as Rix’s book shows, they too are caught up by the beauty of what they “record.”

Poetry, above all, enhances our ideas of flowers. For its recent fine exhibitions linked to Emily Dickinson or Claude Monet, the New York Botanical Garden has been showing apt poetry on placards along the garden’s walks. Visitors could read Mallarmé or Dickinson herself while seeing the flowers that they loved. The garden’s latest exhibition, called “Groundbreakers: Great American Gardens and the Women Who Designed Them,” is displaying poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950) as an accompaniment to the age of the landscape architect Beatrix Farrand and others.

The young Millay was described by an early critic as “a frivolous young woman, with a brand-new pair of dancing slippers and a mouth like a valentine.” She put both to good use, and after a highly bohemian life acquired a blueberry farm in the Berkshire hills. There she wrote poems about nature and gardens, more suitable for the New York Botanical Garden’s exhibition. In 1922, she evokes a woman, surely herself, as seen by a neighbor:

Her lawn looks like a meadow,

And if she mows the place

She leaves the clover standing

And the Queen Anne’s Lace!

Meadow gardening is nowadays the height of wishful fashion.

Surprisingly, the poetry of flowers is often patchy and ill-informed. None of the ancient Greek poets mentions the brilliant wild tulips that run like red rivers through parts of the Greek landscape. Chinese poets focus on a narrow canon of flowers, soaked in symbolism and hidden meanings. They say nothing about the heavenly wild flora, the superb shrubs and mountain flowers that have transformed Western gardens since their collection and introduction by Europeans. John Milton’s poetry describes bunches of flowers that would never flower during one and the same season. No gardener, especially in Britain this year, would agree that April is “the cruellest month” and in no gardens or landscapes known to me does April breed “lilacs out of the dead land,” least of all on the American East Coast within range of the young T.S. Eliot.

The exceptions prove the rule. Sappho had an engagingly sharp eye for the flowers of her native Lesbos, including milk-white pansies. Theocritus’ poems, some three hundred years later, include particular flowers from his second home, Cos, and also from Sicily or southern Italy that he probably therefore visited. Shakespeare of course observed and included many flowers, and D.H. Lawrence was also unusually alert, not just to dark blue Bavarian gentians but to the dark trunks of almond trees, which he acutely observed during his time in Taormina and rendered in poetry there. William Cowper could garden well, but among living poets, only James Fenton has had a garden that challenged expert gardeners with its assemblages of snowdrops and highly unusual plants.

Advertisement

In The Mythology of Plants, Annette Giesecke engages charmingly with a supreme source of fantasy, the “botanical lore” from ancient Greece and Rome. Her originality is to conclude her book with a selection of the plants and flowers mentioned in Ovid’s now fashionable long poem, the Metamorphoses. She even assembles “Ovid’s garden” by picking out flowers from the stories of transformation that are scattered throughout its wearying text. I much doubt if Ovid was ever himself a gardener, not even in his place of exile, wretched Tomi on the northern Black Sea coast. His “garden” comes to him secondhand, through his Greek sources. Giesecke could have said more about them, especially about the Hellenistic epigrams that mark a new phase, from about 200 BC onward, in the literary appreciation of flowers and their metapoetic possibilities.

Ovid’s flora is steeped in fantasy. A constant source for it is the profusion of Greek myths in which sad lovers are transformed into flowers. According to the Homeric hymn in her honor, the goddess Aphrodite threatened the direst penalties to the mortal Anchises after she had just seduced him in bed, if he ever indulged in “kiss and tell.” In the Greek world, disappointed lovers discreetly became flowers and kept perpetual silence. Nowadays, they become aggrieved participants in tabloid journalism or reality TV shows. “Apollo hunted Daphne so,/Only that she might laurel grow,” as Andrew Marvell mused to his coy mistress. Those in antiquity who knew their myths and Greek poetry could see scores of unhappy love affairs in gardens and in nature all around them.

These myths of “transformation” pose problems for earnest modern definitions of a “myth” as a tale applied to an item of social significance. The myths simply attached themselves to items of beauty. Behind those scarlet anemones, from Cyprus to Sicily, there was the blood of the dying young Adonis, gored while hunting. The petals of the hyacinth commemorated Apollo’s dead heartthrob, Hyakinthos. These names pose a complex problem that Giesecke does not address. She assumes the identification of this hyacinth with Hyacinthus orientalis, but I find the assumption difficult, because at most, only the Greek ypsilon, first letter of Hyakinthos’s name, is visible to the eye observing its flowers. An alternative candidate, Scilla bifolia, seems to me and many others to be the better fit, especially for the wondrous carpet of crocus and hyacinth that grew beneath the goddess Hera when she had heavenly sex with Zeus on Mount Ida. Scilla bifolia and crocuses can still be seen in profusion on modern Ida.

However, by the later fourth century BC the “hyacinth” flower was said to be marked with two letters, “ai, ai,” the Greek for “alas.” It then became connected in poetry with the dead hero Ajax (Aias, in Greek). Despite such claims, neither the hyacinth nor the scilla has such markings. Likelier candidates are the wild larkspur, Delphinium ajacis no less, or the wild gladiolus, Gladiolus italicus. In Ovid’s poem one and the same flower is linked to Hyakinthos and Ajax. Reality has been left far behind and it is misleading for Giesecke, here as elsewhere, to pick on a flower in Ovid and write it up as a flower that we still know in nature. Ovid’s “garden” is highly literary.

Giesecke strays between mythology and lore without always observing the boundary fence between the two. As she observes, the ancients ascribed all manner of properties to plants, as readers of Pliny’s Natural History know. An oil made from narcissi was considered to dissolve tumors in the womb. The rind of the red pomegranate was said to be a contraceptive. None of this lore is mythology. I also doubt if mythology was uppermost in the minds of most of the garden owners in Pompeii with whom she begins. She is eloquent about the garden at the House of the Marine Venus in Pompeii, whose wall painting, I might add, was sited to be viewed against the backdrop of the sea and whose naked goddess had the up-to-date hairstyle of a fashionable Roman woman in the age of Nero.

I am less bowled over by its modern appearance than Giesecke is. Like the little back gardens of modern Brooklyn or London’s Fulham, Pompeii’s “town gardens” were often too eclectic in too small a space, a jumble of “features” and allusive bricolage. The houses’ wall paintings indeed show Greek myths, and occasionally the paintings of gardens show maenads. When they prefer to show a profusion of flowers, they are exactly observed, without myth.

Advertisement

They also show birds. Modern gardens have abandoned the charms of aviaries, although rare birds were an important feature for the supreme garden planner of the 1920s and 1930s, the “quiet American,” Lawrence Johnston. At his second home near Menton on the French Riviera, Johnston set a big aviary at the top of his terraced garden where it ran up the hill into informality. It was full of sound, color, and beauty. In this age of environmental correctness, the modern restoration of the garden has not reintroduced the aviary and its caged birds. Multicolored parrots used to fly in the sunlight above Johnston’s deep purple periwinkle.

Literary gardens are the subject of Pleasures of the Garden, the agreeable anthology by Christina Hardyment, which she says she compiled “in a garden studying books about gardens.” She divides her choices by four themes: love, garden design, practical topics, and “solace for body and soul.” Her time span stretches from ancient Egypt to the 1920s and includes many favorites. Under love, she excludes sex, even sex on the woodpile with the gamekeeper Mellors and Lady Chatterley in the flowery clearing around his cottage. Under “practical gardening” she includes meticulous notes from Thomas Jefferson’s diary for the first three months of 1767 when he was only twenty-three years old. “April 4 planted suckers of roses, seeds of althaea & prince’s feather.”

Under the same heading, she includes the once-popular American garden writer Samuel Reynolds Hole, asking people “What is a garden for?” A schoolboy said, “Strawberries,” his younger sister, “Croquet,” and his elder sister, “Garden-parties.” The “brother from Oxford made a prompt declaration in favour of Lawn Tennis and Cigarettes.” Updating Dean Hole’s research, I asked an undergraduate in the Oxford College garden that I run. “Kissing,” he replied, and went back to do so on the lawn.

Hardyment has omitted writers of gardening columns, making her collection much less interesting and memorable. Surely they are “literary” often enough. Vita Sackville-West, writing in her weekly column on deadheading roses in June, is far better than anything here on “solace for body and soul.” When the British expert Arthur Hellyer explained how to prune cobnuts and filberts, he addressed the practicalities with an exactly observed clarity that Hardyment’s quotes from Gerard’s Herbal lack. She represents Hellyer only indirectly, through a line drawing from one of his books showing how to strip turf. Helen Dillon, the modern doyenne of Irish flower gardeners, is much more robust about “design” (“Bugger plans,” she once concluded) than the smug waffle quote here from Joseph Addison.

Hardyment excerpts Jane Austen very well to show us, from a letter of February 1807, that she too was susceptible to wishful thinking about garden plants: “I could not do without a syringa, for the sake of Cowper’s line.” The poet William Cowper had written of “syringa ivory pure.” Ivory-white syringas, or lilacs, are not readily found nowadays, as opposed to ones that are a hard plain white. In a fine scene in Mansfield Park, Fanny Price speaks up to the heartless Mr. Rushworth on behalf of some old avenues by quoting a line of Cowper: “Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.” Austen knew this gardener-poet’s work very well.

Hardyment is sparing with the category of people talking about their own or other people’s gardens. It is a rich one in English fiction, even for authors who are not gardeners themselves. It can express social competition in the pages of Austen or Thomas Peacock or Elizabeth Bowen. It can express moods and unnerving fantasy, in Tennyson’s “Maud” or, above all, in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. Unlike her husband Leonard, Virginia Woolf was a hopeless gardener. However, her short story “Kew Gardens” is a modernist classic, beginning with flowers that are perhaps irises, but hard for me, and no doubt her, to identify.

Has literary wishful thinking ever beset the practical people on whom good gardens depend? Hardyment includes one entry by a working man, Thomas Jones. This Irish bricklayer wrote a self-explanatory poem in 1745, “On a Fine Crop of Peas Being Spoiled by a Storm.” “Ambition’s pride had spurred me on,” its spokesman says, “All gardn’rs to excel.” In her excellent study The Gardens of the British Working Class, Margaret Willes leaves us in no doubt about the role of competition within the proletariat. Lancashire weavers competed in their spare time to grow prize pinks and carnations. Chrysanthemums, dahlias, and sweet peas were prime items of working-class rivalry, intensifying with the spread of flower shows from the 1830s onward. In York, in 1869, a floral contest was introduced for Window Gardening for the Working Classes, but the exhibitors had to prove they were “Bona-Fide members of the working class.” Willes remarks drily, “How this was achieved is not recorded.”

Among the utility and the rivalry, fantasy was still to be found. Some of it filtered down from upper-class patrons and gardens, some from penny magazines. The Ancient Society of York Florists held a working window box contest, but its aim since its foundation, it declared, was “happiness.” Hardyment could have included its show programs in her category of “solace for body and soul.” The great rosarian Dean Hole even reported that once a bedspread was found to be missing from a working couple’s home in Nottinghamshire. His informant thought it had been pawned, but the wife explained that it was being used to keep frost out of their greenhouse. “And please, ma’am, we don’t want it, and we’re quite hot in bed.”

Willes well cites a great survival, the diaries of Charles Snow, a stonemason who worked in the 1880s in Headington Quarry near Oxford. They list his earnings, up to £1 16s, or about $2.70 nowadays, for a week’s work in Oxford colleges. Quite often, they laid him off work for a while. Nonetheless, he lists his daily expenses on his garden, on tulip bulbs and hyacinths, on gladioli, sweet peas, and fuchsias. Not all of it was for resale. He grew flowers, surely, because he loved them too.

Out in wild nature, Carolyn Fry follows The Plant Hunters and their adventures as “botanical explorers.” She writes as a journalist and her book could be subtitled “The View from Kew,” her main source of information being Kew Gardens. Much of its second half is dictated by Kew’s initiatives, culminating in its Millennium Seed Bank, which aims to save seed from a quarter of the world’s flora by 2020. Her story gives less space to fantasy and imagination, but they prove to be hyperactive here too. It is Hardyment, not Fry, who cites the most evocative such international “explorer,” the inimitable Reginald Farrer.

Farrer’s books on his travels in the Dolomites, Japan, and mountains on the borders of China and Tibet are classics twice over. He was a remarkably complex man, who converted to Buddhism in Ceylon in 1907 and was prone to extreme flights of literary fantasy, only partly explained by his Oxford education, where he took a lowly Third Class degree in Greats at Balliol College. His personal story has been excellently told by Nicola Shulman in A Rage for Rock Gardening, but his writings are still unsurpassed.1 The two volumes of his English Rock Garden describe, often in exactly observed detail, hundreds of alpine plants that are unknown nowadays to gardeners.2 Moderns quote them only for their vivid likes and dislikes and their soaring fantasy, but these traits are not the whole story.

At random, I pick out Farrer on a rare rock plant, Phyteuma comosum. Only he has ever observed the variations in its pale bluish and purple coloring, comparing the best varieties to

so transparent an amethystine blue…that they seem like carved jewels from long ago of Tang or Sung, phials wrought by great artists to hold the wine of ghostly ancestors, or the sacred tears of the Emperor for Tai-Chen the Beautiful.

Farrer is also alone in observing the “immense fund of vitality stored in that stout fleshy root-stock.” Correctly, he describes it as “one of the easiest of all alpines.” It is also only he who records in the 1910s its profusion in “the stark iron walls behind the Hotel Faloria at Cortina” up in the Dolomites or “the great-grandfather of tufts, in an impregnable cliff by the bridge going down to Storo in the Val di Ledro.” Like no other collector’s, his mind was an inspiring plant map, one that the ecological mappers at Kew should exploit for their “distribution histories.” He inspired me as a schoolboy to grow a Phyteuma until eventually it was eaten by a lowland English slug.

Unlike his fellow collectors, Farrer had an eye and pen profoundly enhanced by fantasy. He overwrites. He expatiates for pages on the beauty of this primula or the dreariness of that mountain face, adding classical or Orientalist allusions. However, the heart of it all is unforgettable. In 1921 he published The Rainbow Bridge, his account of traveling in 1914–1915 among the gaunt Da Tung alps in China’s Kansu province near Tibet. He notes repeatedly the traces of Meconopsis, the Blue Poppy of the Himalayas, but then he encounters the smaller, pale lavender-purple one in profusion all over the hills. He calls it the “Harebell Poppy,” while knowing it as Meconopsis quintuplinervia:

It was everywhere, flickering and dancing in millions upon millions of pale purple butterflies…. I wandered spellbound over those unharvested lawns.

His companion was plain, blunt Bill, a keen photographer. What, Farrer wondered, was he thinking? “At last he turned to me, and in the awe-stricken whisper of one overwhelmed by a divine presence, he said: ‘Doesn’t it make your very soul ache?’”

For three more pages, Farrer makes his readers ache while he expatiates on his Harebell Poppy, its “multitude and beauty unbelievable.” Typically, he even found and recorded a pure white variety, “exactly what the Snowdrop ought to be, and isn’t.” He concludes with a peroration, also typical of him, on the vanities of wars and men’s ambitions as opposed to the enduring beauty of a flower that “blooms and is dead by dusk.” “Man creates the storms in his teacup, and dies of them,” but these flowers remain “impregnable,” he believes, “as far beyond reach of man’s destructiveness as is man’s own self.” He never thought that man would become these mountain plants’ great enemy by warming and drying out their environment or blasting ever more of their rockfaces to make flooring for apartment buildings.

While pale purple poppies were inspiring Farrer near Tibet, bright red poppies were gaining a new dimension many miles further west. In 1917, just after the year of Farrer’s book, Edmund Blunden wrote in Flanders, with so much blood in mind,

Such a gay carpet! poppies by the million;

Such damask! Such vermilion!

But if you ask me, mate, the choice of colour

Is scarcely right; this red should have been duller.

Farrer, the supreme fantasist, is much the sharpest observer of flowers. His Meconopsis moment still haunts me as an evocation of what there is to see in the world if only one has the nerve, the time, and the organization to go and look at it. Like the seed banks, he too changes life. When he died in the Chinese mountains three years after writing up his Meconopsis, his bearers sent his diaries home. As Shulman poignantly described, his mother took her scissors and cut up each of them into little pieces.

Martyn Rix is himself an outstanding field botanist, an expert on fritillaries, and an intrepid traveler and botanical group leader in Turkey and China. He is also editor of the famous Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, which has appeared continuously since February 1787. Nonetheless, he is sensitive to Farrer and his eye and includes his fine sketch of the rock daphne, Daphne petraea, observed in the Tyrol. This plant is the variety that Farrer uses in his text to describe the best habitat of that “amethystine” rock daphne. He is as exact a botanical artist as he is in one aspect of his prose.

Rix’s superb book is extremely handsome. It is a mine of concise observation, resting on his rare expertise. Many of his chosen artists came from backgrounds in medicine or practical trades. He is admirably clear that the greatest specialist is still Pierre-Joseph Redouté, “the son of a painter and decorator” in the Ardennes. He was patronized by Napoleon’s Josephine and remains the king of botanical art for his famous paintings of bulbous plants (enhanced by the technique of stipple) and roses. Rix observes so well that “in a moment of serendipity, six great botanical illustrators found themselves working together towards the end of the eighteenth century.” They included Redouté and his brother and their very important mentor, Gerard van Spaendonck. At the same time, natural historians “were undertaking exciting expeditions, and the specimens of plants, rocks, and animals they collected came flooding into the Paris Museum.” Under the conservation protocol of Kew and many other modern botanical gardens, there could be no such “flood” nowadays.

We live in a great age of botanical illustrators, as Rix admirably documents, but they are not working on new specimens shipped directly in from the wild. Rix considers that “there have probably been more beautifully illustrated botanical monographs published in South Africa in recent years, than in all the rest of the world.” One of the best shows the lovely dieramas, Venus’s Fishing Rods for wishful thinkers, against the penciled setting of their habitat, the Drakensberg Mountains. In South Africa “there are small populations of very rare species that may become extinct.” A painting in the field may be their “lasting monument.”

Farrer’s world of romance and observation has gained a new dimension. He too painted plants, and in his wake, gardeners still cultivate some of his introductions, keeping them safe beyond the killing fields of their homelands. “Mortal dooms and dynasties are brief things,” he wrote, “but beauty is indestructible, if its tabernacle be only in a petal that is shed tomorrow.” Those petals now live on safely in the art of many floral groups, patronized by botanical gardens in the Bronx or Brooklyn, Australia, London, or South America.

This Issue

September 25, 2014

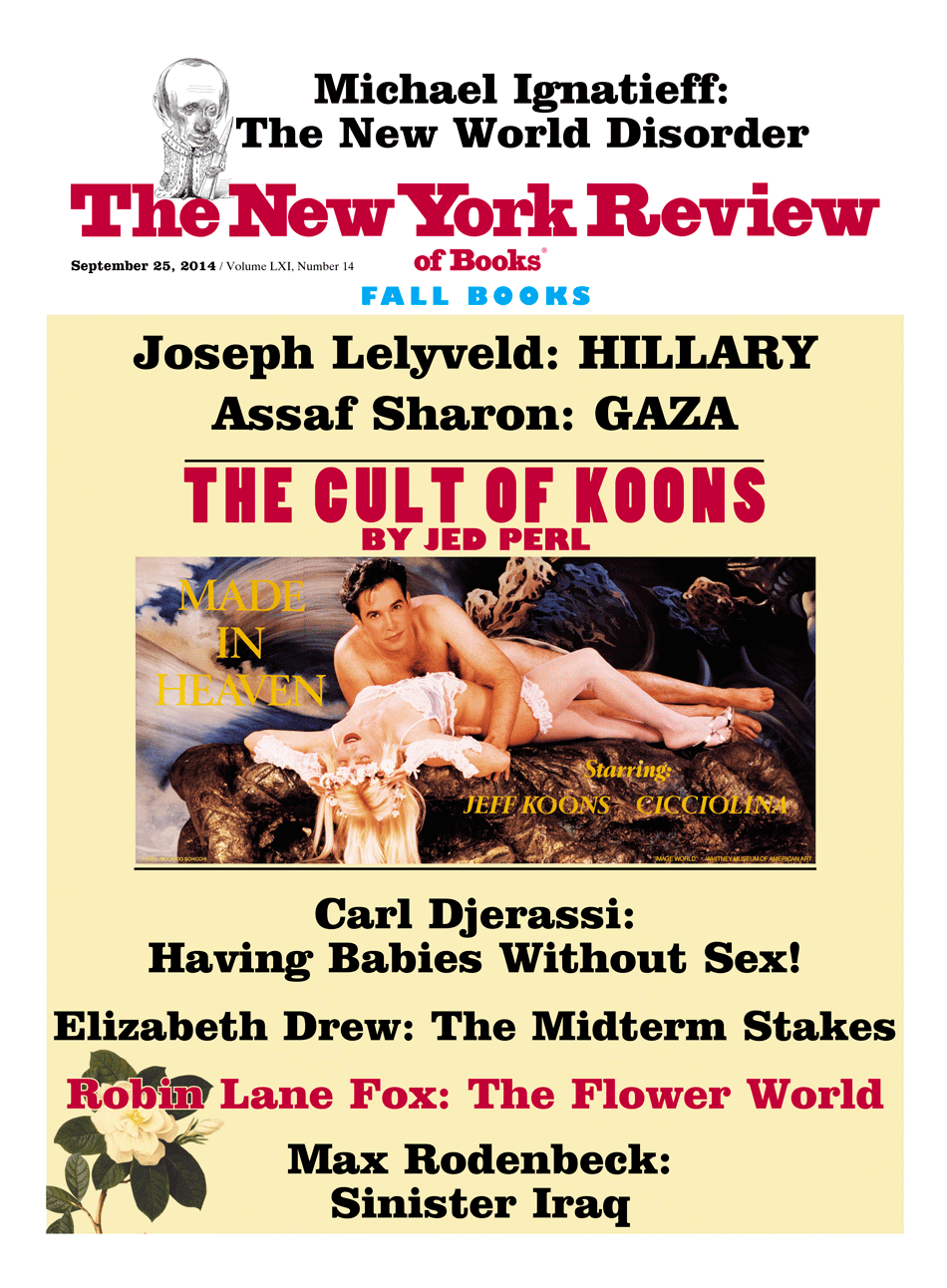

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Obama & the Coming Election

Failure in Gaza