At his first inauguration, Barack Obama rejected “as false the choice between our safety and our ideals.” On his second day in office, he announced plans to close the Guantánamo detention facility within a year and to end immediately George W. Bush’s authorization of the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” a euphemism for torture.

Sadly, those steps in January 2009 turned out to be the high points of Obama’s determination to end Bush’s trampling of basic rights in the name of fighting terrorism. Whether the issue is torture, Guantánamo, military commissions, drone attacks, or electronic surveillance, Obama’s tenure has been one of disappointment for those who had hoped for a more consistently rights-respecting approach to combating terrorism.

Torture, paradoxically, has been the area where Obama’s policy has been both the firmest and the most qualified. By all available evidence, use of the “enhanced interrogation techniques” has stopped. Obama also prohibited further use of secret detention facilities where suspects had “disappeared” in CIA custody for torture. (To be fair, Bush by the end of his presidency seemed to have ended both too.)

However, the Convention against Torture, which the United States ratified in 1994, not only prohibits torture and other mistreatment but also requires that it be investigated and punished. On this latter obligation, Obama has utterly failed. The Obama Justice Department has not prosecuted anyone for Bush-era torture. It has conducted only a narrowly focused investigation into interrogation techniques that exceeded those authorized by Bush’s Justice Department, and that investigation yielded no prosecutions.

It was left to Congress, most notably the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence under the chairmanship of Senator Dianne Feinstein of California, to conduct a more comprehensive investigation. In December, it released a 528-page summary of a 6,700-page report on the CIA’s Bush-era torture.

A principal finding of the report is that the “CIA’s use of its enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees.” It is sad that we must even debate the efficacy of torture, given that the legal and moral prohibition of torture is among the strongest we have. The Geneva Conventions, for example, forbid it even in time of war. But when facing a serious security threat, as the United States did after the September 11, 2001, attacks, it can be tempting to rationalize the illegal and immoral as necessary, so this finding that torture was ineffective matters.

The CIA challenges this conclusion. While acknowledging that mistakes were made, it insists that “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which the Senate report shows to have been far more brutal than previously thought, did produce actionable intelligence. Yet it should give us pause that Democratic and Republican senators who have studied the report conclude that torture was ineffective, while the greatest proponents of its utility are the torturers themselves. As described in more detail in this issue by Mark Danner, the detainee about whose interrogation we probably know the most—Abu Zubaydah—reportedly provided interrogators with a trove of useful information before the CIA waterboarded him but then stopped once the waterboarding began. A contested argument of utility is a flimsy one on which to rest an exception to so fundamental a prohibition as the ban on torture.

The CIA also maintains that its “enhanced interrogation techniques” did not constitute torture. Even Obama says that torture was used: he famously commented that “we tortured some folks” and that “I believe waterboarding was torture.” But the CIA says it was entitled to rely on contrary legal opinions issued by the Bush Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. Yet the Senate report shows that the CIA knew from the beginning that the techniques it planned to use were torture. An internal CIA draft letter to the attorney general seeking a formal declaration that the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques would not be prosecuted acknowledges that the techniques violated the US torture statute. When the Justice Department’s Criminal Division refused to provide this immunity, the CIA went shopping for more malleable lawyers in the Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, and found them. Later, when seeking further authorization, the CIA lied to the Justice Department. That history hardly suggests a reliance in good faith on the advice of counsel.

Moreover, anyone reading the OLC opinions—the notorious “torture memos”—can readily see their strained, intellectually dishonest attempts to justify the unjustifiable. They were transparent efforts to lay the foundation for precisely the defense of torture that the CIA is now advancing—that it relied on official legal advice, so it is unfair to second-guess it now.

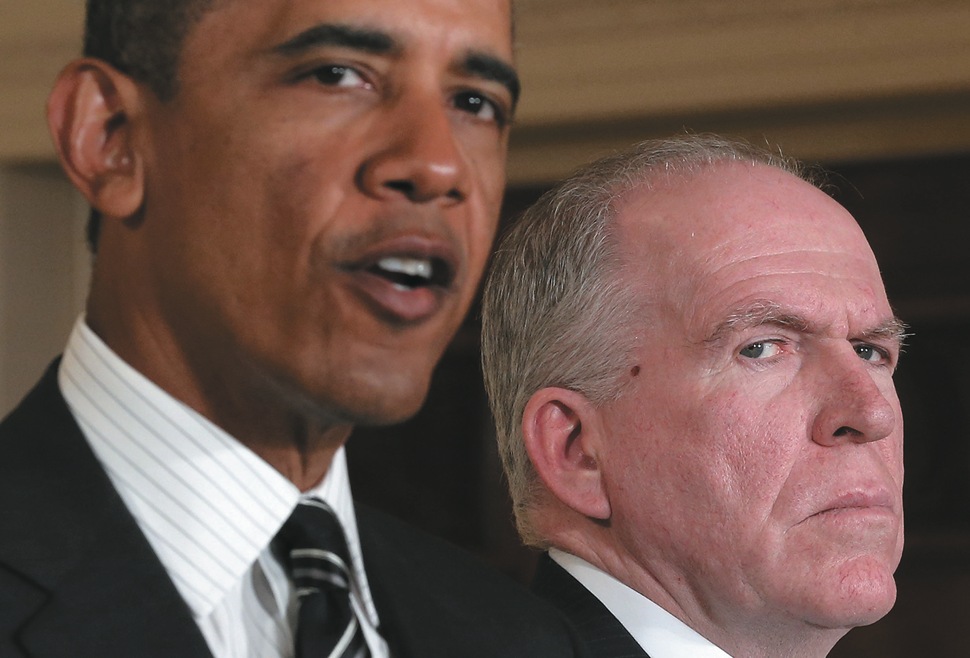

Obama’s refusal to investigate, let alone prosecute, Bush-era torture means that, practically speaking, torture remains an option for policymakers rather than a criminal offense. CIA director John Brennan has explicitly refused to rule out the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques under a future administration. The message to future presidents facing a serious security threat is that the prohibition of torture can be ignored without consequence. Abusive security forces from around the world are likely to take heart from that precedent as well.

Advertisement

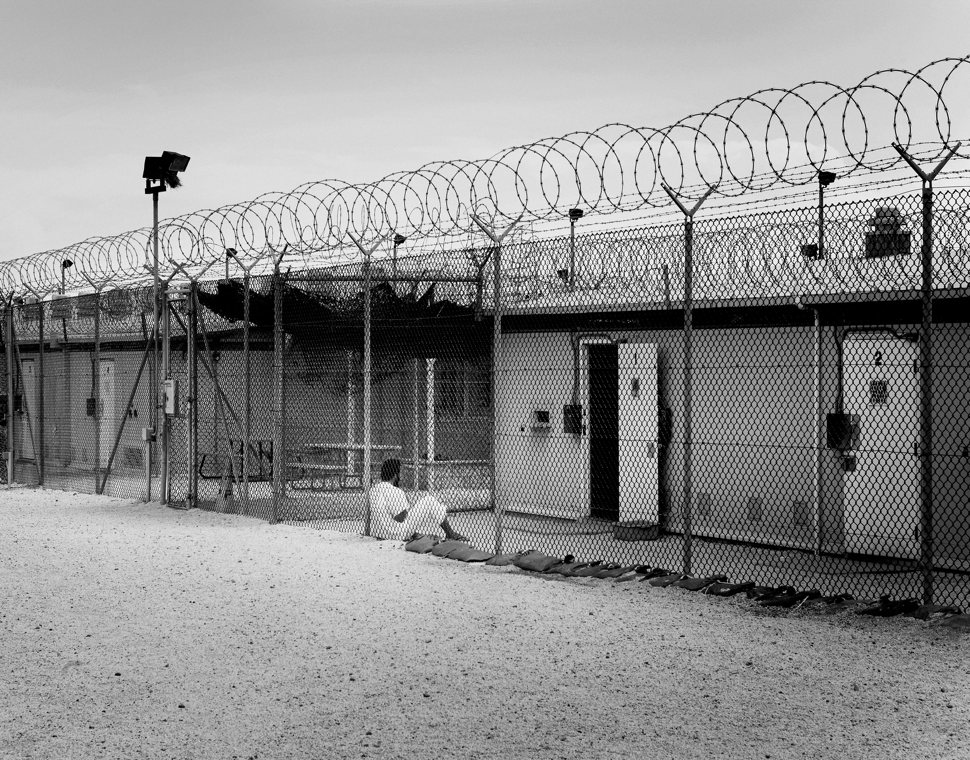

Obama has done little better when it comes to his vow to close Guantánamo. The good news is that the president has refused to bring any new detainees to Guantánamo. In his six years in office, terrorism suspects captured abroad have been delivered instead to regular federal courts for trial. So Obama has stayed true to his vow to treat Guantánamo as a problem that he inherited rather than one that he compounds.

Under Obama, the number of detainees has fallen—from 241 when he took office to 127 today, including twenty-eight released in 2014. However, despite a recent flurry of efforts, there has been no real progress toward shutting down the facility, which annually costs the American taxpayer roughly $3 million per detainee. All but a few of these men have been held in Guantánamo for over a decade without even being charged with a crime, let alone being tried.

The detainees can be divided into four broad groups. The first, and most prominent, are the five suspects in the planning of the September 11 attacks, as well as two others who have been charged with specific crimes and three who have been convicted, two by guilty pleas and one by an uncontested trial. Early in Obama’s presidency, initially with his backing, Attorney General Eric Holder sought to have the September 11 case tried in federal court in lower Manhattan. If the trial had been held as planned, it would probably have long been completed and, in view of the respect accorded the New York federal courts, widely seen as fair.

However, those plans were scuttled in the face of opposition from New York’s then Mayor Michael Bloomberg and a host of mostly Republican senators and representatives, who said they were worried about the alleged security risk and contended that it was inappropriate to try the suspects in civilian rather than military court. It didn’t matter to them that the New York authorities had a long history of prosecuting mafia dons, drug kingpins, and even World Trade Center terrorists without incident. Nor did it matter that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his September 11 codefendants were eager to portray themselves as warriors for whom a military trial is desirable rather than the “mere” murderers that a civilian trial would imply.

Instead, the prosecutions for September 11 and a handful of other cases have been pursued in Guantánamo before military commissions—a jerry-rigged institution that is being built and tested even as it attempts to handle one of the highest-profile cases of the century. That is also where a second group of twenty-three detainees are to be prosecuted, but none of them has even been charged despite, in many cases, having spent nearly thirteen years in detention.

The commissions have not fared well. Many of their problems stem from the Obama administration’s decision to keep classified all evidence about the CIA’s use of torture against six of the seven defendants currently being tried—a decision now being questioned by the military commission judge in light of publication of the Senate report on CIA torture. That approach has made it difficult for defense counsel to challenge the evidence. In addition, lax rules on the use of hearsay seem designed to allow the prosecution to avoid having to call interrogators as witnesses. Rules also permit the introduction of evidence that results from torture, as well as coerced testimony so long as the evidence comes from a witness and not a suspect. As one new legal issue after another requires adjudication, the military commissions have been subject to repeated delays, making them unlikely to complete (or perhaps even begin) the trials for taking part in the September 11 attacks before Obama leaves office.

The administration has determined that a third group of fifty-nine Guantánamo detainees do not pose a threat that would justify continued detention. Of these, fifty-two are from Yemen, but the administration has refused to release them on the grounds that the security situation in Yemen is too volatile—even though there seem to be few if any restrictions placed on other recently released detainees. Of the other seven, some cannot be returned to their home country for fear of persecution; but no other country has been found to take them. Efforts to resolve these cases are underway and should be vigorously pursed.

Advertisement

The administration has designated a fourth and final group of thirty-five detainees “too dangerous” to release but says either that there is insufficient evidence to prosecute them or that they have not committed a chargeable crime. In the meantime, they languish in Guantánamo, without ever receiving a trial or a fair opportunity to contest any evidence against them. Even if some might pose a risk if released, so do many other people around the world who are free to go about their business unless they commit actual crimes. If they pose a risk, moreover, there is no reason why they cannot be the subject of surveillance after they are released. Why do these few dozen prisoners remain in Guantánamo?

The answer seems to lie not in security but politics. The difference between risks to Americans from the Guantánamo detainees and risks posed by countless others is what might be called the Willie Horton problem. If a random person somewhere in the world commits an act of terrorism, that is a tragedy, but Obama has no special political responsibility for it other than the general duty of all presidents to try to safeguard Americans. But if a Guantánamo detainee released by Obama commits an act of terrorism, Obama would be held responsible in the same way that Michael Dukakis was famously tarred, with devastating political effect, for having allowed weekend furloughs to a number of convicts including the murderer Willie Horton, who then raped a woman.

Early in his presidency, Obama had the legal authority to handle the cases of the Guantánamo detainees as he wished, but Congress eventually imposed various restrictions on moving the detainees to the United States or transferring them to their home or third countries. Obama threatened to veto these bills but instead signed them. With the new Republican-controlled Congress, it is unlikely that these restrictions will be lifted. However, even under the existing legislation, Obama retains considerable authority to release uncharged detainees and to send them either to their home countries or, for those facing persecution there, to third countries. And he could veto any future bills that unnecessarily restrict his ability to close Guantánamo or transfer detainees.

Obama has been similarly disappointing in clarifying the body of law that governs the use of aerial drones for targeted killing. If drones are deployed in the course of armed conflict, the laws of war allow using them to attack an opposing “combatant”—generally, a member of the enemy’s armed forces—whether or not the target is then engaging in or threatening a hostile act. Documents recently disclosed by Edward Snowden suggest that US drone attacks in Afghanistan may have been targeting not only the Taliban and al-Qaeda but also military-age men or drug producers without proof that they were combatants; but there is no question that the laws of war govern drone attacks in Afghanistan and the tribal areas of northwestern Pakistan, as well as recent attacks on ISIS in Syria and Iraq. These are all places of active armed conflict to which the United States is a party.

However, the United States under Obama has also used drones to attack terrorism suspects in Yemen and Somalia. These countries are mired in armed conflict but the US government does not claim to be a participant. Rather, the United States targets people who are said to pose a threat of terrorism. What law governs in those circumstances?

The Bush administration answered this question by invoking the global “war on terror,” but that had troubling implications. If the entire world is a battlefield, what would stop the United States from summarily killing people on the streets of London or Paris on the grounds that they are ostensibly members of a terrorist force? Few would feel that such an approach is legitimate, and the Obama administration claims to have jettisoned it.

Instead, the United States could respond to a terrorist threat in places like Yemen as a problem of law enforcement, proceeding under international human rights law rather than the laws of war. Law enforcement personnel may at times use lethal force, but only as a last resort to stop an imminent lethal threat. For example, the government might shoot someone holding a gun to the head of a hostage, but not someone on his way to commit an act of terrorism who could be arrested instead.

In a May 2013 speech, Obama came close to recognizing this legal limitation. He spoke of a US drone policy that is “heavily constrained,” one that targets only individuals who pose a “continuing and imminent threat to the American people,” and that reflects “our preference…always to detain” rather than kill. However, it seems that it was Professor, not President, Obama speaking, since he never stated that law enforcement rules would apply or released the legal memos governing the program (beyond the special case of killing a US citizen). As a result, we have no idea what rules for drone use are in fact being prescribed away from active war zones or whether they are being followed.

Since Snowden’s revelations, there has been much public debate about the US government’s use of electronic surveillance to monitor our communications. Few would object to targeted surveillance directed against suspects reasonably believed to be plotting terrorist acts. But there are several troublesome dimensions to the government’s mass surveillance.

To begin with, the government takes the view that we have no privacy interest at all in our metadata—the electronic information identifying the people we telephone or e-mail, as opposed to the content of those communications. This information can be extraordinarily revealing about our personal lives, but the Obama administration, like Bush’s, claims that we have no reasonable expectation of privacy because we already “share” this information with a phone or Internet company.

This assertion is premised on a 1979 Supreme Court case concerning telephone calls. That case easily could have been decided the other way, by a ruling that the phone company has a fiduciary duty to preserve our privacy comparable to the duty owed us by a lawyer or doctor with whom we communicate, and that “sharing” information with a telephone company is not a waiver of our privacy. But the consequences of that rationale for waiving concern for privacy were limited when the court made its ruling because the Internet did not then exist and metadata for phones had to be compiled by hand. Today, however, the government’s fathomless computing capacity combined with the centrality of electronic communications to modern life permits extensive invasions of our privacy. Even the Supreme Court has hinted that it may overturn its 1979 decision.

Part of the government’s argument for scooping up our metadata is that it needs a haystack to find a needle. Without collecting enormous quantities of metadata, the government fears it will have nowhere to search should the need arise. To justify this approach, it claims that our privacy is not implicated when it collects our metadata, only when it “queries,” or looks at, it. But by that theory, the government could run a video feed from our bedroom to a government computer and claim we had no reason to object on privacy grounds until someone actually watched the video.

Controversial as these positions are, they are also apparently unnecessary, because the government has yet to identify a single terrorist plot that could not have been stopped without the government’s mass collection of our metadata. Nor has the government explained why targeted subpoenas to communications companies, which themselves routinely keep metadata for considerable periods for business purposes, would not suffice.

Once more, Obama has given a good speech on the matter, but his words do not appear to have been implemented as policy. In January 2014, in a speech at the Justice Department, he vowed that the government would stop amassing our metadata and instead rely exclusively on targeted queries to communications companies. That has not happened. In November, legislation supported by Obama that would have made these and other changes failed to overcome a Senate filibuster.

Without congressional action, Obama could, if he wanted, simply not seek a renewal order authorizing bulk metadata collection from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, an order that is required every ninety days. Yet the president has petitioned the court for renewal of this authority four times since his January speech, most recently in December.

Moreover, Obama has not addressed another troubling aspect of US electronic surveillance—the view that foreign citizens outside the United States have no right to privacy even in the content of their communications. Given the amount of global communications traffic routed through the United States, as well as US surveillance capacity abroad, this view means that the US government considers itself entitled to listen to the phone calls and read the e-mails of any foreigner abroad. And because of the difficulty of distinguishing a foreigner from a US citizen by their electronic communications, the United States scoops up the phone calls and e-mails of many US citizens as well. In those cases, the privacy of Americans is protected only by after-the-fact procedures to “minimize” the intrusion. These procedures themselves contain ample exceptions such as for broadly defined foreign intelligence.

Needless to say, this narrow view of the right to privacy is hardly popular with the rest of the world, where people are understandably reluctant to have the United States comb through their most intimate communications. It has provoked two backlashes, one healthy, the other not. On the positive side, Brazil and Germany have led an initiative at the UN General Assembly to articulate global concern about the harm of mass surveillance for our right to privacy and other basic freedoms. In addition, there will be an effort at the UN Human Rights Council in March 2015 to create a special rapporteur on privacy who could elaborate global standards for communications regardless of where people are located.

On the negative side lie efforts to reduce intrusions into privacy by limiting the extent to which a nation’s communications and data can be made available to other nations. Because of the vast US surveillance capacity, other governments have reservations about their communications flowing through the United States, and some in Europe and South America are contemplating requiring data to stay in their country. There are practical problems with these efforts—it is far from clear that as fluid an instrument as the Web can be contained within national borders—but also serious threats to freedom of expression.

To protect free electronic communication, the first rule for communications companies operating in countries with strong censorship regimes like China is not to store communications data in that country. That makes it harder for the country to seek the identity of dissidents, critics, and others who might be punished for their private communications if their identity were known. However, if democratic governments begin requiring that communications data stay within their countries, they will invite a similar response from countries like Russia and China, with damaging consequences for privacy and free speech.

One can only speculate about the reasons for Obama’s disappointing record on rights and counterterrorism. It is possible that in some cases he feels that Americans’ security demands certain compromises in their rights, but he has never made that case, and his rhetoric has consistently stressed the opposite. Rather, ensuring a counterterrorism policy that respects basic rights seems simply not to have been a priority for him.

Obama may have felt that the people who care most strongly about these issues are already firmly in his camp so their views could be ignored without political consequence. He may not have wanted to spend the political capital needed to rein in the powerful and potentially vindictive intelligence agencies that have been at the heart of most counterterrorism abuses. Or he may have calculated that acting in these areas to control those abuses would alienate elements of the Republican Party whose votes he needed to pursue domestic priorities, whether Obamacare or immigration reform—not that his reticence seems to have bought his administration much support.

Still, one virtue of a lame duck president is that he no longer has to worry about the next election. And given the Republican dominance of Congress, there is even less reason now to expect compromise on Obama’s domestic agenda than there has been over the past six years. So this would seem an opportune moment for Obama to contemplate a more principled approach to counterterrorism—as both a statement of American values and a signal to other nations that terrorism can be fought while respecting rights and the rule of law.

As he has in matters of environmental protection, immigration reform, and normalization of diplomatic relations with Cuba, Obama can take significant steps under his executive authority, without the need for legislation. These would include allowing criminal investigation of the officials who authorized the CIA’s torture, shutting Guantánamo, ending the military commissions, announcing clear rules for drone use, and embracing effective limits on intrusions into privacy by electronic surveillance. With his legacy at stake, it is still not too late for Obama to demonstrate that our security indeed does not depend on abandoning our rights.

—January 8, 2015