Granger Collection

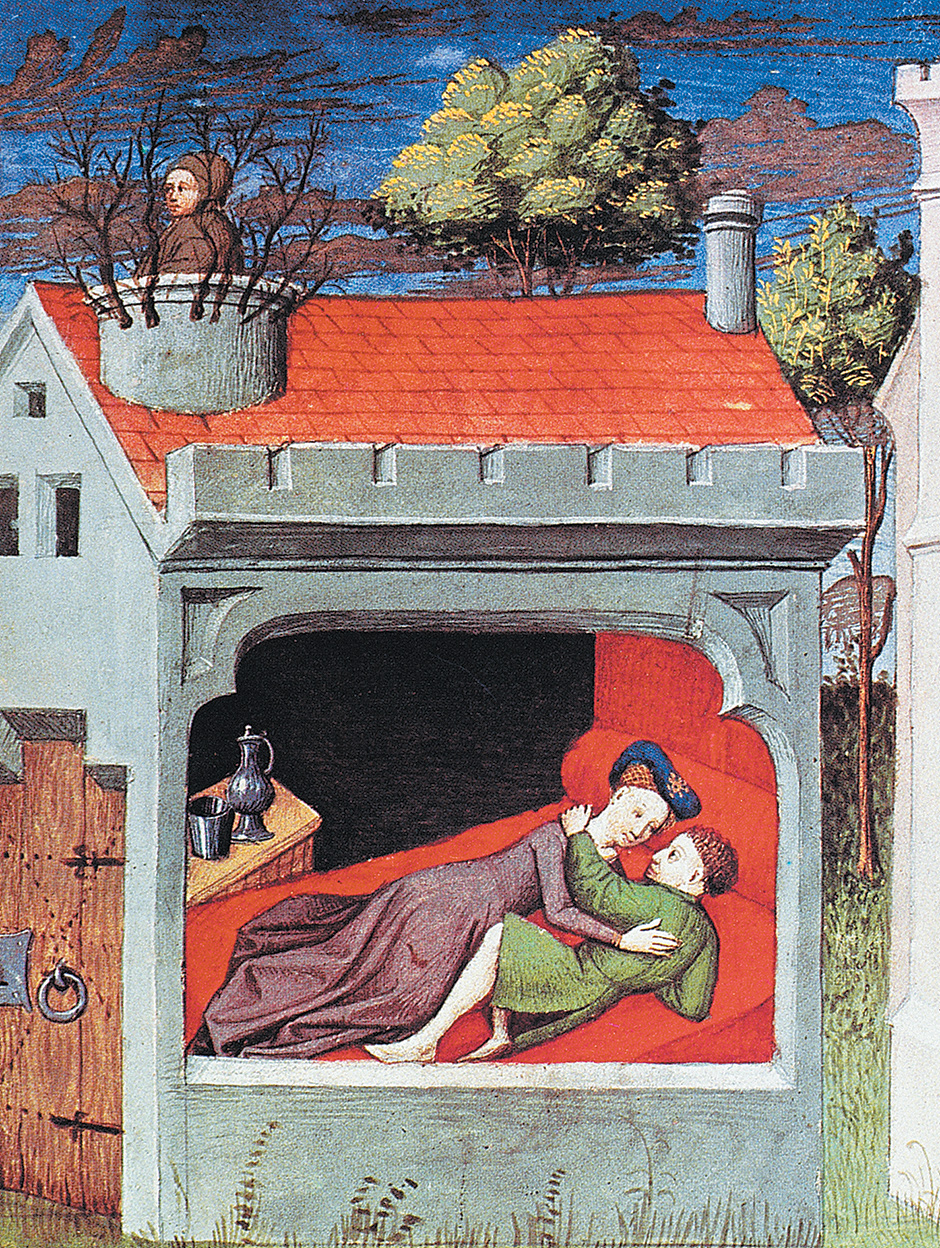

A Flemish miniature from a French translation of Boccaccio’s Decameron, circa 1430. The fourth day of the Decameron includes the story of Ghismunda, the daughter of Prince Tancredi of Salerno. Ghismunda fell in love with Guiscardo, a virtuous but humble valet in Tancredi’s court, and the two began meeting secretly in her bedroom. When Tancredi found them together (here he is shown spying from the chimney), he had Guiscardo killed and his heart sent to Ghismunda in a golden chalice. Realizing what her father had done, she poured poison into the cup, drank the concoction, and died.

What was he supposed to do? His father, who held a position in an important Florentine banking firm, expected him, perfectly reasonably, to follow in his footsteps. But Giovanni Boccaccio, who was born in or near the Tuscan town of Certaldo in 1313, dreamed of being a poet. When he was seven, before he had even seen a book of poetry, he was, or so he claims, already writing verses. Childhood friends nicknamed him “the poet.” His father was kind and indulgent—though a bastard, little Giovanni was quickly legitimized and given a proper education—but he was not inclined to be reckless. Poets generally starved. Giovanni could study Dante as much as he wanted in his spare time, but he would learn how to make a living.

For six years the young Boccaccio struggled to accommodate himself to an apprenticeship in merchant banking, but to no avail. He hated it. His father, who had by this time moved to the bank’s offices in Naples, relented, at least to the extent of allowing his son—whose intellectual promise he clearly recognized—to enter the Neapolitan Studium (in effect, the university) to study canon law. It was another disaster. Again, Boccaccio recalled, he lost nearly six years. The course of study was so nauseating to him that neither the urgings of his teacher nor the authority of his father nor the reproof of his friends could make him stay with it. His love of poetry was invincible.

But if Naples was stony soil for the potential canon lawyer, it was to be a garden of delights for the aspiring writer. In the fourteenth century, as for a long time afterward, Naples was culturally and intellectually buoyant. At a time when cattle grazed in the ruins of the Forum and thugs terrorized the remaining inhabitants of Rome, Naples was one of the largest, wealthiest cities in Europe.

Boccaccio, who had a gift for friendship, met an impressive group of writers and scholars and found his way into the court of Robert the Wise, the Angevin king who ruled Naples and all of southern Italy. The sophisticated court, with its air of elegance, learning, intrigue, and erotic adventure, was a heady place for a young poet. Boccaccio was present in 1341 when the king, an ardent patron of the arts, personally conducted over two and a half days a formal public examination of the great poet Petrarch. Upon the successful completion of the examination, Petrarch was sent, with a royal letter of commendation and the king’s own purple robe, to Rome, where on the steps of the Capitol he was crowned with a laurel wreath. In retrospect the event marked the symbolic beginning of the great cultural movement known as the Renaissance, and even at the time the symbolic significance was hard to miss: it was as if the ancient world, the world of Augustus and his poet laureate Virgil, had come back to life.

The twenty-eight-year-old spectator at this ceremony, still a rank unknown, did not venture then to make the great Petrarch’s acquaintance; it would have seemed presumptuous. Some years later, after Boccaccio returned to Florence and became a diplomat in the republic’s service, the two became close friends. Petrarch exercised a powerful influence over the younger man, leading him into an ever-deepening engagement with classical studies, Greek as well as Latin.

Among the fruits of this engagement were the tomes Boccaccio wrote in Latin, including a vast, chaotic dictionary of ancient myths, The Genealogy of the Pagan Gods (De genealogia deorum gentilium), a series of moralizing biographical sketches of the fall of famous men and women (De casibus virorum illustrium), an account of the greatest women in history (De mulieribus claris), and even a learned treatise on geography, based largely on ancient sources (De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis seu paludibus et de diversis nominibus maris). Boccaccio no doubt regarded these as among his truly important works—just as Petrarch regarded his long Latin epic, the Africa, as his own greatest achievement—but they are all now largely unread, except by scholars dutifully working their way through the Complete Works.

Similarly neglected for the most part now is the poetry on which Boccaccio staked so much of his hope for lasting fame: the epic Teseida (which gave Chaucer his Knight’s Tale), the gigantic terza rima folly in fifty chapters called The Amorous Vision, the charming pastoral Fiesolan Nymph, and so forth. There is quite a bit more. Boccaccio lived what for the time counted as a long life (he died in 1375 at the age of sixty-two), and he seems to have written with astonishing facility and ease.

Advertisement

But all that really counts at this point, more than seven hundred years since the year of his birth, is a single vast work, written neither in prestigious Latin nor in heroic verse but in energetic, inventive, wonderfully flexible, and often earthy Italian prose. The work, of course, is the Decameron.

The English translation of the Decameron recently published by Wayne A. Rebhorn, a professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin, is notable first and foremost for its scope. Not a selection of the most famous bawdy episodes, not a genial anthology of the different genres with which Boccaccio worked, but every one of the one hundred stories, plus the famous introduction and all the linking narratives and poems. The whole comes to 860 pages; 947 if you count the voluminous notes. The book is handsomely printed, in a highly legible font and with decent margins, making it a pleasure to read and own, but it is a brick. I confess that, though my commendatory words are featured on the book jacket, I read most of it on a Kindle, making my seatmates on planes and trains wonder what I was chuckling about.

I have always mused a bit when the French say about a novel that it is traduit de l’américain, but I understand it better now, for Rebhorn’s is definitely a translation from Italian into American. The stories are liberally sprinkled with words such as “guy,” “muttonhead,” and “buddy” and with phrases like “big shot,” “one heck of a constitution,” and “I really loved her a whole bunch.” The colloquialisms will no doubt grate on some readers, and the slang seems particularly jarring used in such close proximity to sentences like “The hour of nones was already upon them” (“nones” being one of the canonical hours for liturgical prayers). But even in its dated, often slightly musty attempts at demotic ease, the overall effect is, I found, oddly charming, and for a simple reason. Many of these stories are scandalously obscene, but the scandal has nothing to do with filthy words. “She was a good-looking, lively gal, brown and buxom, and she really knew the art of grinding at the mill better than any other girl around.”1 “Gal” here effectively helps to set up Boccaccio’s characteristic comic periphrasis, “grinding at the mill.”

Such circumlocutory words, or periphrases—the lady “lay in his arms and taught him how to sing a good half-dozen of her husband’s hymns”; “If you were squeezed till you were dry, they couldn’t get a spoonful of sauce out of you”; “I’ll do my best to get others to board my boat and carry them through the rain”—have nothing to do with prudery. They are part of Boccaccio’s inexhaustible bag of metaphorical tricks, and they work because, except for the crudest and most tongue-tied of us, everyone resorts to such tricks constantly, if rarely with such inventiveness. As Boccaccio writes in “The Author’s Conclusion,” “Men and woman generally…go around all day long saying ‘hole’ and ‘rod’ and ‘mortar’ and ‘pestle’ and ‘sausage’ and ‘mortadella’ and lots of other things like that.” The point is not that such words should rightfully be innocent of double entendres but rather that we gleefully carry our sexual energy over into everyday language, and we love it. It is part of what it means to be healthy and alive.

Being healthy and alive is central to the whole project of the Decameron. The book opens with a celebrated account of the horrendous outbreak of the Black Death—bubonic plague that seems to have originated in Asia—that struck Europe in 1347–1348 and wiped out enormous numbers of people all across the continent. Florence, with its large population crowded tightly within the walls, was one of the cities particularly hard hit. Current estimates hold that about 60 percent of the inhabitants of the city and its surrounding countryside perished.

Boccaccio evokes, with a power worthy of the famous plague account in Thucydides, not only the public health catastrophe but also the unraveling of the entire fabric of civilized life. Writing as if he had witnessed these things for himself (though he had probably been in the safer environment of Naples), he describes the onset of the disease—the swellings the size of eggs or apples that suddenly appeared in the groin or under the armpit—and its terrifyingly rapid unfolding into black and livid blotches all over the body followed by virtually certain death. The virulence of the contagion and the ubiquity of the dead and dying led to a collapse of public authority in the state and the church, and, still worse, to a collapse of the familiar, cherished forms of social intimacy.

Advertisement

The sick were left to their own devices: neighbors fled from neighbors, brothers kept their distance from brothers, wives abandoned husbands and husbands wives. “What is even worse, and almost unbelievable, is that fathers and mothers refused to tend to their children and take care of them, treating them as if they belonged to someone else.”

The social rituals with which humanity ordinarily deals with loss and grief quickly broke down. The funeral pomp of candles, priestly chants, and weeping relatives disappeared. The dead were pushed out of doors and left to rot in the streets; the smell of decay was everywhere. Enormous trenches were dug in the graveyards of churches, and impoverished porters were paid to collect the corpses and tip them into the ground “by the hundreds, stowed layer upon layer like merchandise in ships, each one covered with a little earth, until the top of the trench was reached.”

In the midst of this horror, Boccaccio writes, a group of seven young well-bred women found themselves together by chance in the church of Santa Maria Novella. All deeply shaken and depressed, they were sitting silently when one of them, Pampinea, had a sudden idea: Why don’t they leave the city, with their few remaining maidservants, and go off to one or another of their country estates, “having as much fun as possible, feasting and making merry, without ever overstepping the bounds of reason”?

Such liberty would not ordinarily be possible for unmarried women of their class, but circumstances had changed: they had all been abandoned by their kin and were now doing nothing but passively and miserably awaiting death. It was time to escape. The friends immediately agreed. Having decided that it would be good to have some male escorts on their expedition, they were pleased when three suitable, equally well-bred young men also entered the church and quickly consented to the plan. They all left the city the next day.

Once they put the afflicted Florence behind them, the scene and mood of the Decameron shift with a suddenness that is possible only in fiction. Birds trill in flowery, fragrant, mosquito-free gardens surrounding lovely palaces with elegant halls, beautifully painted bedchambers, and vaulted cellars stocked with precious wines. The group at once decides to organize its festivity; random pleasure-seeking would smack more of desperation than of the health they are seeking. They elect a queen—Pampinea, of course—who proposes that during the warmest hours of the day, they sit together in a shady corner of the garden and each in turn tell a story. They will repeat the game on subsequent days, each governed by a different “ruler” who will set a common theme for the day or permit everyone to choose a topic at will. Ten friends, and, with days off for Sabbath prayer, ten days—a hundred stories. The game is set.

Boccaccio did not sit down, in the wake of 1348, and pen the hundred stories that were first published all together as the Decameron in 1353. He had in fact been collecting and writing up some of them during his years in Naples, and they were by no means all his own invention. Like Shakespeare, he loved to steal from others—often, in the case of Boccaccio, from the French fabliaux that were evidently in circulation in the Angevin court2—and like Shakespeare, he had an uncanny ability to improve on whatever he stole.

But the frame of the plague—so discordant and dire—gave Boccaccio something more than a fictive occasion for assembling the diverse tales that he had, magpie-like, picked up wherever he could find them.3 The plague gave him an underlying motive for the whole enterprise, a motive he himself may not have grasped when he first pored over this or that collection of novelle, looking for suitable material. Storytelling, the frame of the plague insists, is medicine against misery, despair, and death. It is a way of choosing and prolonging life.

This does not mean that all of the stories in the Decameron are cheerfully life-affirming. There is a strong strain of cruelty and sadism in quite a few of them, a strain that reaches its climax in the concluding tale of the entire work, the story, apparently Boccaccio’s own invention, of patient Griselda. Here Gualtieri, the Marquis of Saluzzo, takes as his wife the beautiful daughter of a penniless peasant. He marries her with great pomp and honor, and her subsequent charm, kindness, and graciousness seem to bear out the wisdom of his unconventional choice. She bears him a daughter, but shortly after this happy event he has a sudden impulse—no explanation given—to test her patience.

He does so by telling her that his vassals are grumbling that a mere peasant’s daughter has given birth to his child. She replies humbly that she knows she is unworthy of the honor he has bestowed on her. He then decides to intensify the test by sending a servant who indicates to her that he has instructions from his lord to take away the infant and put her to death. Though sick at heart, Griselda immediately takes the baby from the cradle and hands her to the servant: “‘There,’ she said to him, ‘do exactly what your lord, who is my lord as well, has ordered, but don’t leave her to be devoured by the beasts and the birds unless he’s told you to do so.’”

This is only the beginning of a sequence of fiendish tortures and humiliations, almost unbearable even to recount, to all of which Griselda responds with astounding patience. In the end, of course, she gets back everything that has been ripped away from her, and we are told that Gualtieri “lived a long, contented life with Griselda, always honoring her in every way he could.” We could join in the long chorus of interpreters who associate the tale with the medieval reception of the Book of Job and celebrate the heroine as a model of Christian fortitude in adversity.4 We could, in a different vein, say that the perverse pleasure of the story lies in the mystic marriage of the perfect sadist and the perfect masochist. Or, as I would prefer, we could take seriously the words with which Dioneo, the young man who tells the story, brings it to an end:

Who, aside from Griselda, would have suffered not merely dry eyed, but with a cheerful countenance, the cruel, unheard-of trials to which Gualtieri subjected her? Perhaps it would have served him right if, instead, he had run into the kind of woman who, upon being thrown out of the house in her shift, would have found some guy to give her fur a good shaking and got a nice new dress in the bargain.

Scuotere il pilliccione: to shake the fur. We are back to the sex for which the Decameron is most famous. And with good reason, for it is not only amusing but also—even now, after seven centuries—often surprising.

In Lombardy there used to be a convent, goes a story told by one of the ladies, renowned for the holiness and religious zeal of its nuns. One of them, a young beauty named Isabetta, fell in love with a handsome young man whom she had glimpsed through the grate, and managed to find a way to rendezvous with him, “not once, but many, many times, always to their mutual delight.” But one night the young man was spotted leaving by one of the other nuns who, along with several others, secretly plotted to have the pious abbess catch the violators in the act. Soon enough they found their chance, and they rushed to knock on the door of the abbess’s room, crying, “Get up, Reverend Mother, and hurry. We’ve discovered Isabetta has a young man in her cell.”

As it happened, however, the abbess was having her own pleasures with a priest. In her haste to get dressed in the dark, she picked up and put on her head what she thought was her veil but turned out to be the priest’s breeches. All the nuns sat in the chapterhouse with their eyes demurely lowered, listening to the outraged abbess’s blistering condemnation of the guilty Isabetta, but when the disgraced girl happened to raise her eyes, she suggested that the abbess tie up her cap. As the others looked up as well, the abbess realized what had happened and abruptly changed her tune. Since “it was impossible to defend oneself from the goadings of the flesh, she told them all that they should enjoy themselves whenever they could, provided it was done discreetly.”

The goadings of the flesh—gli stimoli della carne—drive Boccaccio’s characters to violate all the rules. Cloistered nuns break their vows and cunningly contrive to satisfy their desires; young men cheerfully seduce the wives of their best friends; demure brides quickly tire of their husbands and look around for suitable lovers; servants betray their lords and hop into bed with their ladies. Priests, monks, and mendicant friars are, as everyone in Boccaccio’s world understands, particularly on the prowl for sex wherever they can find it. “Don’t be so surprised, sweetheart,” says an abbot, renowned for his holiness, to the peasant’s beautiful wife whom he has just propositioned; “This isn’t something that diminishes saintliness, for that resides in the soul, and what I’m asking you for is a sin of the flesh.” Besides, he adds:

Your beauty is so ravishing, so powerful, that love forces me to act like this, and let me tell you, when you consider how pleasing your loveliness is to saints, who are used to seeing the beauties of heaven, you have more reason to be proud of it than any other woman.

The abbot gets his way, the wife has a jolly time, and when she gets pregnant, her dumb, pious, cuckolded husband is deceived into bringing up the bastard as his own child.5

“Love forces me to act like this”: the explanation would have come as no surprise to contemporary readers of the Decameron. The fourteenth century was the heir to almost a thousand years of endlessly reiterated Christian homilies on the power of what Saint Augustine in the fifth century regarded as the mortal sin of “concupiscence.” Sexual arousal, Augustine wrote in Against Julian, is not like any other human desire:

Does it not engage the whole soul and body, and does not this extremity of pleasure result in a kind of submersion of the mind itself, even if it is approached with a good intention, that is, for the purpose of procreating children, since in its very operation it allows no one to think, I do not say of wisdom, but of anything at all?

And the terrible thing is that this compulsive, involuntary stirring of the flesh lies at the origin of every human being. It is the way we are all conceived, and it marks each and every one of us with the ugly taint of original sin. “Any friend of wisdom and holy joys,” Augustine concluded in The City of God, “would prefer, if possible, to beget children without lust.”

What is startling is that not one of Boccaccio’s characters—certainly none of his priests and nuns—seems to share this pious preference, even for a moment. They are all too feverishly busy trying to enhance and satisfy their desires. This could, of course, merely confirm the saint’s darkest view of fallen humanity’s universal guilt. But though Boccaccio’s characters on occasion feel frustration, embarrassment, shame, vexation, and fear, they appear to be entirely immune from guilt. Adultery, betrayal of friendship, violation of religious vows, homosexuality, ménages à trois, ménages à quatre: the goadings of the flesh make a mockery of all social and religious pieties.

The immunity from guilt extends to the ten narrators of the stories. True, the young gentlemen and ladies abstain from storytelling on the Sabbath in order to pray (and, we are told, to allow the women to wash their hair): they are, after all, not social rebels but well-born Florentines. But a lifetime of religious indoctrination seems to have left them only with further resources to express sexual desire. The vivacious Filomena concludes her story in which a clever wife tricks a friar into helping her meet her lover with what counts as the Decameron’s principal form of piety: “And I pray to God in His holy mercy that He will lead me, and all those Christian souls who are similarly inclined, to the same happy conclusion.” Theirs is a world in which an erection can be exuberantly described as “the resurrection of the flesh.”

How could this world have come into being? Perhaps the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century loosened, at least on Boccaccio and his circle, the tight grip of Christian orthodoxy. Or perhaps the grip was never all that tight. The intense revival of Augustinianism by sixteenth-century Protestants, especially Luther and Calvin, has tended to create an illusion of widespread, virtually inescapable popular faith, as if everyone at the time were in the grip of religious anxiety and eschatological hope. And the Protestant caricature of the Middle Ages as an age of limitless credulity has only extended the illusion back into the past. But if the Decameron is any indication, many people shrugged and longed for something else.

Late in his life Boccaccio seems to have undergone a religious conversion. He took holy orders and contemplated burning his earlier profane works. But instead of consigning the Decameron to the flames, he did something else. In 1370–1371, shortly before his death, he copied out in his own hand the whole enormous work. One can only hope that his achievement gave the old sinner the immense pleasure that reading it continues to give us.

This Issue

January 8, 2015

In Ferguson

A Better Way Out

Who Is Not Guilty of This Vice?

-

1

The truth is that the original is much better: “La qual nel vero era pure una piacevole e fresca foresozza, brunazza e ben tarchiata e atta a meglio saper macinar che alcuna altra” (Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, edited by Amedeo Quondam, Maurizio Fiorilla, and Giancarlo Alfano [Milan: BUR, 2013], p. 1214). But what do we expect? Boccaccio’s fourteenth-century imitator, Chaucer, comes closest to the right spirit: ↩

-

2

English-language readers now have access to a marvelous collection of these often spectacularly raunchy French comic tales in verse: The Fabliaux, translated by Nathaniel E. Dubin, with an introduction by R. Howard Bloch (Liveright, 2013). See Christopher Ricks’s review in these pages, December 5, 2013. ↩

-

3

Like the plague bacillus, stories could travel long distances and remain alive. One of Boccaccio’s sources, as Rebhorn observes, was the Panchatantra (Five Heads), a Sanskrit collection of stories, circa 500 CE, with a frame narrative. Boccaccio seems to have encountered this text in a Latin translation based on a Hebrew version based on an Arabic version based on a Persian version. ↩

-

4

The story served for some readers as a wholesome antidote to the obscenities that made them squeamish. Thus, the author of the entry on Boccaccio in the 1926 edition of the Encylopaedia Britannica: “A creation like the patient Griselda, which international literature owes to Boccaccio, ought to atone for much that is morally and artistically objectionable in the Decameron.” ↩

-

5

In 1573 the pope authorized the publication of an expurgated edition of the Decameron, including the obscene stories, but required that the priests and friars be changed into laymen. ↩