Barney Frank, who looks like Barney Rubble and talks like a speeded-up Will Rogers, was keeping something from us—not just, for a long time, his sex life, but his hidden formation as a professor. As a stellar graduate student at Harvard, he completed all the requirements for a Ph.D. except the dissertation, for which he had chosen a subject (the legislative process) and a director (Samuel Huntington). Later he added a Harvard law degree to his academic achievements. The models he had chosen to follow on the Harvard campus were John Kenneth Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

Even as a teenager, Frank knew that he was irrevocably dedicated to two things that threatened to cancel each other out—men to love and politics to better the world. At that time, an openly gay person could not be successful in politics, and a closeted one risked exposure if he called too much attention to himself—Frank would, for this reason, dread campaigning as a minefield. He thought he might indulge both his passions if he stayed on the sidelines as a professor giving advice during frequent sojourns in Washington (the Galbraith-Schlesinger model). He knew that men in Congress often had spouses living in their districts, so a single man in Washington would not be anomalous.

Frank showed a genius for politics that was recognized even as a graduate student. He was a teaching assistant at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, director of graduate student affairs there, and organizer of the Visiting Fellows Program (which brought in major political figures to lecture at the school). In the latter capacity, he drove around campus the liberal activist Allard Lowenstein, who became his friend and recruited him for planning the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi.

After finishing his Harvard course work that summer, he went to Mississippi, where his rapid-fire Jersey accent made him useless for recruiting blacks to vote; but he helped verify places on the alternate delegation the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was assembling for the Democratic convention that year. He noted with alarm that a principal selling point for this delegation to replace the all-white official delegation was that this one would be integrated. It was easier to claim that there would be whites in the MFDP slate than to get white men to risk action against the white establishment. Always a realist, Frank warned the MFDP representatives at the convention against making a boast they could not live up to. He made his warning effective with a multiple pun: “Hold your fire until we hear the ayes of our whites.”

As he returned to Harvard to take his Ph.D. orals, Frank stopped off in Washington to report on the Mississippi results to Joseph Rauh, the lawyer drawing up a brief for the MFDP delegation. Without money, he asked a young woman he had met at National Student Association meetings to put him up for the night. Cokie Boggs (later Cokie Roberts) lodged him in the basement of her parents’ house without their knowledge. When Frank emerged the next morning, he surprised Cokie’s father, Congressman Hale Boggs, who was sitting alone at the breakfast table. Boggs was gracious, but he asked Frank not to let his Louisiana constituents know he had sheltered a man they would consider an outside agitator in their South.

Back in Massachusetts, having passed his orals, Frank was getting notice in political circles. Michael Dukakis, then a state legislator, asked him to join the staff of the Democratic Study Group, where he did research for the policy issues they were debating. Then, in 1967, Kevin White asked him to help run his campaign for mayor of Boston. Frank was anxious to help White against his opponent, Louise Day Hicks, the leader of South Boston’s opposition to racial integration, so he got permission from Professor Huntington to take a year off from writing his dissertation.

Frank then made himself so useful that White, having won the election, asked this graduate student to be his chief of staff in the mayor’s office. Frank, fearing that it would be too exposed a position for a closeted gay, resisted; but White said he needed Frank, and if he failed as mayor Frank would feel guilty. Frank said he could not again put off the writing of his dissertation; yet White, who was a friend and neighbor of Huntington, said, “We’ll get Sam to give you a deadline extension of a few years.”

Barney Frank the would-be professor faded from view in the office of the mayor of Boston. He had found his métier—that of backroom bargainer. This let him assuage the guilt of what he calls his own “cowardice” as a closeted gay by working for the rights of other minorities, foreseeing problems, solving them, or skirting around them:

Advertisement

I was in the grief business…. To my pleasant surprise, I was good at it. I ran political interference for administrators, refereed disputes among them, listened to public grievances, pushed the bureaucracy to respond and, not least, helped the press secretary explain all of this to the media.

White, with Frank’s help, built on the black support he had earned by opposing Louise Hicks; he did this so well that Boston largely avoided the riots that tore other cities apart after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1970, after White ran and lost a campaign for governor, Frank felt it was time to move on. He considered an offer to return to Harvard, where Richard Neustadt had promised him a fellowship at the Institute of Politics; but before he could accept that offer he was given another chief of staff post, this time in Washington. Michael J. Harrington (not the Catholic socialist writer) had known Frank at the Democratic Study Group, when Harrington was in the Massachusetts state legislature. Now, after being elected to Congress on an antiwar ticket, Harrington decided he needed Frank’s skills in the House of Representatives. Frank did not stay in Washington long this time. Friends back in Massachusetts felt he should run for a seat in the state legislature himself. They calmed his fears of exposure in an unfriendly district, claiming that Boston’s Ward Five was ideal for him. He realized they might be right:

By every demographic indicator, it differed from the rest of the city in ways that were favorable to me—or, more precisely, that minimized my electoral disadvantages. The median length of residency in the city was near the bottom, which meant that voters in the area were less likely than voters elsewhere in the city to hold my own recent move to Boston [from D.C.] against me. The heavy dose of Harvard on my résumé would have been at best a mixed blessing elsewhere; it was a great credential in a district with the city’s highest level of educational attainment. The ward also had a low percentage of families with children. There were not yet identifiably “gay” areas, but there were more single people on the census rolls than in any other constituency. The district also included a large subsidized-housing development and one of the few genuinely racially integrated areas in Boston.

The ordeal of the closeted gay man means that choice after choice must be weighed in such finely calibrated scales. Perils, and relief from them, mean something different to the man forced to hide his identity, to accept even ugly alternatives to the dangerous truth. Frank overheard the state treasurer, a close friend of Mayor White, hold up a meeting until Frank could be there: “Wait. Where’s the fat Jewish kid?” Others might resent such a dismissive description. Frank welcomed it warmly, since he knew the addition of one more word would have ended his career entirely—he was listening for, and did not hear, that word being added: Where’s “the fat Jewish gay kid”? Frank describes how he had continually to guard his language, to “desex my pronouns.”

The strain of living in the closet takes a heavy toll on your personality. And it is hard to keep the anger that should be directed at your own self-denial from spilling over into dealings with others. When I think of the politicians I deem likely to be taking this approach, a disproportionate number share my reputation for being too quick to give and take offense.

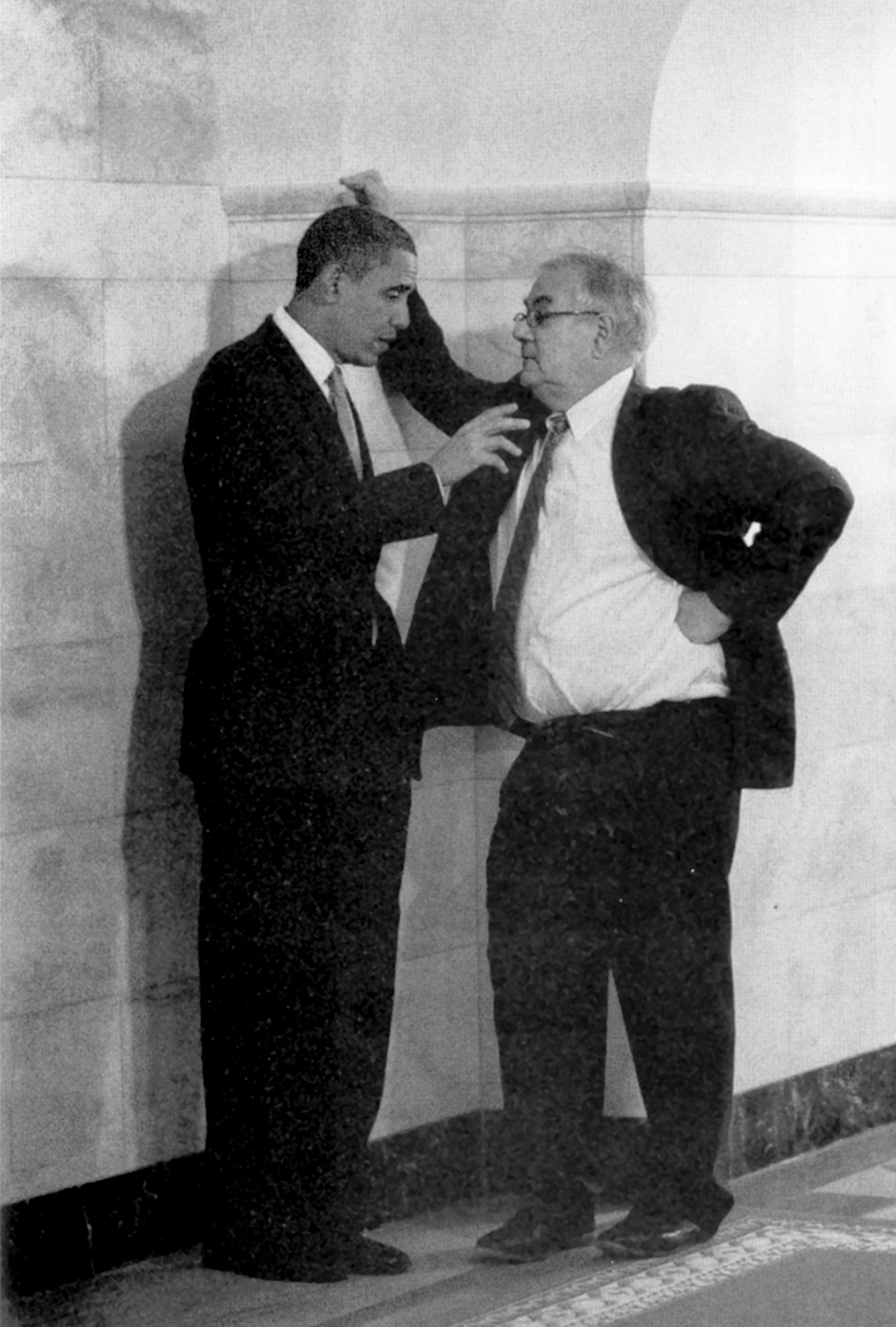

The need to hide one’s sex life, however sparingly indulged, condemns the closeted to furtive, shallow, and demeaning sexual encounters. It was only when he outed himself that Frank was able to have a sound and open relationship for eleven years with Herb Moses and then the full married relationship he now has with Jim Ready. President Obama celebrated the social merit of such ties when he inscribed a picture for Ready, “To Jimmy—Showing you love for keeping Barney under control! Barack Obama.”

Frank has lived into an era (and helped bring it about) when socially damaging pressures that kept men and women in the closet have been eased. Those pressures made him, at one point, commit perjury when suddenly asked under oath if he was a homosexual. They deprived us of the full talents of many leaders, some of whose energy was drained into maneuvers of self-protection.

Frank does not feel free to force others into the freedom he arrived at so late; but when the RNC (then chaired by the poisonous Republican consultant Lee Atwater) began to accuse Democratic House Speaker Tom Foley of homosexuality, Frank loudly proclaimed that he would begin releasing the names of closeted Republicans in the House who denounced homosexuals. Atwater quickly asked Foley to assure Frank that he was ceasing the war. One of the more rickety aspects of the Republican Party, as of the Catholic clergy, is that each simultaneously denounces and is populated by closet gays. That house of cards is challenged by what this book calls “the Frank rule,” that “the right to privacy does not include the right to hypocrisy.”

Advertisement

Being the victim of prejudice during his early career had its damaging effects on Frank (and on society in general); but it made him especially sensitive to other victims—the poor, blacks, and women. I had occasion to notice that after I taped an interview with him and put in print a witty remark he let slip about a House colleague of his. A problem with being so quick with a quip is that Frank can suffer what he calls “wisecracker’s remorse.” In this case, he called and asked me to send a copy of the tape to him—not, he assured me, to challenge my account; but since the target of his quip was also a subject of prejudice against a minority, he wanted the full context so he could frame an apology in the most healing way.

Frank’s empathy for the excluded may be one reason his admirers and his detractors both think of him as a kind of liberals’ liberal. But much of his book, as of his career, has been spent calling out certain lefties as dopes. It began when he was an undergraduate at Harvard, just arrived from his Bayonne, New Jersey, home, where he had pumped gas at this father’s truck stop. In Cambridge he heard the liberal icon Pete Seeger wow a packed Harvard audience with a song mocking “ticky tacky” homes that “all look just the same.” Frank knew that many people in these postwar housing projects were proud of owning their first home, and owning it with government aid. Affordable housing would be one of Frank’s greatest concerns throughout his political career, and he could never understand people who ridicule others’ modest successes.

When he went to Mississippi, he noticed that his fellow do-gooders mocked middle-class values to blacks who just want to join the middle class. It is now fashionable to blame contempt for government on Tea Partiers; but Frank saw the same attitude earlier, and on the left—in all those who said they were defying “the System.” The radicals blamed liberals for being too bourgeois. Frank blamed them for not being bourgeois enough. He left before the MFDP was defeated at the Democratic convention in 1964, but he had foreseen its demise. The party’s delegation was not accepted as a whole but, with the help of Joe Rauh and others, two of them—one white, one black—were given seats with the white delegates.

The MFDP, with fine scorn, rejected this compromise, and let the all-white delegation sit for their state. Frank thinks they should have acted on this partial victory, since it is overwhelmingly likely that the regular delegation would have bolted the convention rather than sit with blacks. Other southern states had declared their intention of doing that if the MFDP slate had been accepted. Just imagine how the TV cameras would have focused on that one black face in a sea of white. Frank saw a pattern here that would be repeated in left-wing protest movements:

There is a price to pay for rejecting the partial victories that are typically achieved through political activity. When you do so, you discourage your own foot soldiers, whose continued activity is needed for future victories. You also alienate the legislative partners you need. A very imperfect understanding of game theory is at work here. Advocates often tell me that if they give elected officials credit for incremental successes, they will encounter complacency and lose the ability to push for more. But if you constantly raise your demands without acknowledging that some of them have been satisfied, you will price yourself out of the political marketplace. When members of Congress defy political pressure at home and vote for a part of what you want, they are still taking a risk. Telling them you will accept only 100 percent support is likely to leave you with nothing.

Frank says that the left should imitate the National Rifle Association, which does not rely on demonstrations and street theater but on constituent letters, lobbying of elected officials, and—above all—voting. In one of the biggest gay rallies of its time, that of 1993, nearly 700,000 marchers showed up in Washington, but only a few hundred went to lobby their congressmen and women. Frank prevented some of the counterproductive aspects of the march, persuading a chorus line of soldiers in drag not to do a Rockettes routine. But he was unable to head off a lesbian comedian when she described Hillary Clinton as “finally a first lady she would like to ‘fuck.’” (The remark was broadcast live by C-SPAN “and widely cheered by the march audience.”)

Frank contrasts these rude demonstrations with the order and discipline of the civil rights movements, planned by savvy participants like A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Andrew Young. At the famous March on Washington in 1963, speeches were vetted beforehand to make sure they were persuasive and not offensive. “If a black comedian had begun to joke about having sex with Jackie Kennedy, he would have been thrown in the Reflecting Pool, not cheered.” It was his own disciplined willingness to bargain and be responsible that made Frank so much in political demand.

Frank would not have left his safe state legislative district to go to Congress if Pope John Paul II had not opened up for him an equally liberal and tolerant district when he ordered Jesuit Father Robert Drinan to resign his seat in the House. The pope thought Drinan too liberal—and in his place he got Frank, a gay Jewish atheist. (As Frank’s frequent ally the Catholic Nancy Pelosi told me, “Way to go, Pope!”)

Frank fears some forms of “big government”—especially our monstrous financing of exotic weaponry, occupying forces around the world, and the wars we start rapidly and end (if at all) after guaranteeing our own defeat. But he knows that the same people who hand out huge contracts for this overkill capacity are calling for “small government” when its services could help the poor, or disabled, or ordinary citizens. They base their claim that government does not work not on the part that really does not work, the defense that we make too big to control, but on service to our own citizens. They are following the “starve the beast” strategy of men like David Stockman and Grover Norquist—declare that programs cannot work, deregulate them as not worthy of correction, underfund them, and then, when they do not work, declare the first presumption vindicated.

Frank was horrified when Bill Clinton said, in effect, that the starvers were right but that he would starve government moderately. After the president in 1996 declared, “The era of big government is over,” Frank says he wanted to ask, “What country are you describing?” And he asked Clinton’s staff, “Did I sleep through the big-government years?” The logic of the professor he might have been is deployed here:

I recognized no period during my service in Congress that his words remotely described….

The “New Democrats” allied to Clinton were pursuing a strategy that would not work. Their plan was to accommodate anti-government sentiment in general while attempting to increase government in the particular. But there was a logical flaw: A whole cannot be smaller than the sum of its parts. This is true of the political world no less than the physical one.

Frank fought mightily for the government actions that help people. He sees that free health care works for Congress, for the military, even for prisons—then why deprive other citizens of it? On issue after issue, Frank has been commonsensible, nonhysterical, and patient with his fellow legislators. He knew that the real animus against big government was a protective maneuver for big business. The former was made too small to work so that the latter could become too big to fail. Frank always said that neither one should prevail against reasonable oversight and regulation. His long labors in this vein culminated in the modest bank regulations of the Dodd-Frank bill, which is energetically opposed by the banks and their Republican servitors.

Frank was right about his purpose at the outset. He was in the grievance business, looking for what heals, what holds people together, what advances a cause, if only incrementally. His rule of action was “willingness to settle for the best achievable outcome in a given set of circumstances.”

I had a glimpse of his parliamentary skills when I served with him on a committee set up to oppose Reagan-era cuts in funding for the publication of historical documents. Frank was the one who moved the conversation along, softened disagreements, or raised practical difficulties. He was not the chairman of the committee (William Leuchtenburg was) and his old undergraduate role model, Arthur Schlesinger, was on the panel, but the unobtrusive leader was clearly Barney. I said to him after the meeting that I was sorry I would never be able to vote for him as the first gay president of the United States. After reading this book, I am sorrier than ever.

This Issue

June 4, 2015

The Climate Club

Bernini: He Had the Touch