The Boswell family tomb lies beneath an old building in the Scottish town of Auchinleck. When you go down the steps into the black vault, you are immediately enclosed in a coldness that troubles your own bones. The air is damp—a struck match goes out, then a second—and the experience is less of visiting a grave than occupying one.

The other day, I blindly felt the walls and touched a metal plaque before remembering my phone has a flashlight. “Sir Alexander Boswell, Bart,” it says on the plaque, giving the date of his death. This man, I knew, was the eldest son of the famous biographer. He died in a duel in 1822, at Auchtertool in Fife, after insulting a certain nobleman in the pages of a short-lived journal, the Glasgow Sentinel. Alexander was a member of Parliament and a baronet, which explains the relatively posh memorial. His father, the genius of the place, is buried in the adjacent wall and his crypt is marked with chalk: “JB.”

The biographer’s grandfather, another James Boswell, who died in 1749—once a “big, strong, Gothic-looking man,” an advocate who “never understood a cause till he had lost it three times,” according to Frederick Pottle1—has a large crack in his crypt through which I could see, resting on dust, his Yorick-like skull. Above him is the grave of Boswell’s daughter Veronica. In a letter to his friend William Temple, the biographer once described how he held Veronica in his arms one morning and told her she would one day be taken from her grave into the fine things of heaven. He frightened her but he couldn’t help it. “I saw death,” he wrote, “waiting for all the human race, and had such a cloudy and dark prospect beyond it, that I was miserable as far as I had animation.”

Boswell was subject to the “black foe,” a fear of death that somehow acted as a guiding light to his philosophy.2 In an odd way, being in his tomb was like being in his mind, for there never was such a lively fellow who dwelled more on death. As a young man in Holland, he could wake up shocked from a dream in which he was condemned to be hanged. He was changeful, but his mind was a constant chamber of ghosts and religious horrors. “I awake at night dreading annihilation,” he wrote, “or being thrown into some horrible state of being.”

That dread state of being invigorates the drama of self for Boswell, giving him both reason and impetus, and he shared with Samuel Johnson a deep sense of worry about his end. We think of the two of them on the London highway, making for drinks at the Mitre, at the apogee of their lives (if not yet of life-writing), but what also bound Boswell to Johnson was a shared fear of death. “It is neither pleasing, nor sleep,” writes the latter; “it is nothing. Now mere existence is so much better than nothing, that one would rather exist even in pain than not exist.” In Boswell’s Enlightenment Robert Zaretsky shows Boswell intervening at this point, “insisting that God would never allow for such a possibility. Johnson cut him short: it is in the ‘apprehension of it that the horror of annihilation consists.’”

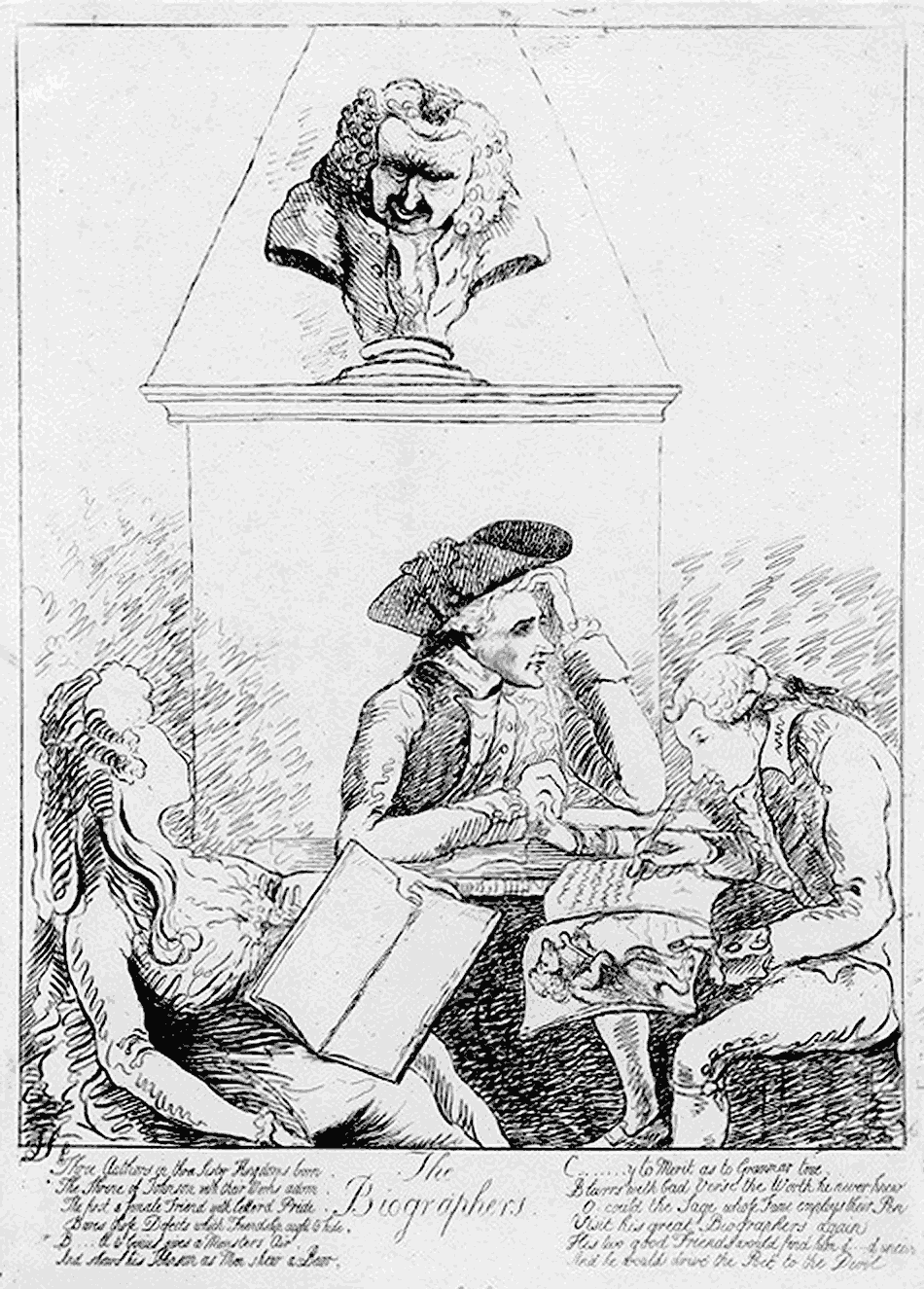

Boswell was, at the same time, a self-delighter and a self-tormentor, and indeed his style depends on the notion that selfhood must be the strongest currency. This is true not only of his journalizing but of his biography, too. Boswell loved presence. We find him least interested in Johnson when the doctor is without the company of his future biographer. (In the sizable Life of Samuel Johnson, the great man’s background, and his scrofula-ridden early life, are dispatched in less than a hundred pages.) In 1950, post-Freud and post-Kinsey, Boswell appeared, in the full flurry of his self-consciousness, like a very modern man—his London Journal 1762–63 was a huge best seller when first published that year—but Zaretsky’s buoyant and rigorous “intellectual adventure” is a successful attempt to place the writer within the broad tapestry of the European Enlightenment.

The Edinburgh that Boswell grew up in was a new Athens, and the cobblestones of the High Street were no strangers to the tread of genius—to David Hume and Adam Ferguson, to Lord Monboddo and James Hutton—and neither were the streets of Glasgow, where Boswell attended lectures and befriended the economist Adam Smith. The atmosphere of the Scottish Enlightenment would have young Boswell firing on all cylinders, yet like his Ayrshire neighbor, the poet Robert Burns, the ferment in his mind was also an outcrop of the new Continental thinking. Boswell admitted of more contradiction even than Burns, climbing, arm-in-arm with his friend Temple, to the top of Arthur’s Seat, the famous hill overlooking the city of Edinburgh, where they would loudly proclaim their loyalty to the new freedoms of Voltaire and Rousseau.

Advertisement

Zaretsky helpfully and correctly refuses to see the Enlightenment as having been simply one thing. But for Boswell it was always a movement, or movements, to supplant the certainty of systems with the vagaries of selfhood. “Was there even a place for the soul,” asks Zaretsky,

if man was, as Locke declared, a blank slate or, as the French philosophe La Mettrie later affirmed, a machine? Were the soul and the self one and the same? Was the self yoked to the body? Or, as Locke also suggested, was it the sum total of an individual’s experiences—that which “has reason and reflection, and can consider it self as it self?”

It turns out that Zaretsky’s book is a primer for the kind of rationale that makes someone like Boswell, because it shows the force of individual personality on the action of a period. From the best writers of his day Boswell lifted ways of being more thoroughly himself. “The Enlightenment had no final port or destination,” Zaretsky writes. “It is this endless voyage that defines the nature of the Enlightenment. If it were a ship, the Enlightenment’s name could well be Sapere Aude: ‘Dare to Know.’”

The phrase was Immanuel Kant’s, and it was “commandeered” by Scottish thinkers. “Today it is from Scotland that we get rules of taste in all the arts,” wrote Voltaire, “from epic poetry to gardening.” And it may be argued that Boswell, via David Hume—not the first and not the last of his father figures—actually absorbed the lessons of several enlightenments, allowing a tremendous unspooling of personality into the circus of his prose. Boswell is a man of his time, and one is content to follow his intrepid journey out, sponsored by Zaretsky, to see just exactly how his intellectual experience formed the person we came to love—open, self-promoting, self-hating, and funny.

Boswell changed the game, adding to the art of living on the page. Previous writers have their natures (Pepys does, Defoe does, Montaigne does, and so do the Evangelists), but only with Boswell do we begin to observe a new, modern talent for self-adaptation. In Zaretsky’s book, we see the effect of one great mind upon another, again and again, and thus we see the evolution of Boswell’s dazzling prose style. Witness David Hume placing experience before essence, thus shaking young Boswell’s faith in exterior sovereignty. And here’s Adam Smith, who reveals, via The Theory of Moral Sentiments, how a human being is apt to modulate his or her emotions and his or her expression so as better to gain the applause of the world.

Boswell’s moral faculties were affected by these figures, and by others such as Lord Kames and Frances Hutcheson, to the point where the old Calvinist sense of duty gives way to a more Romantic way of being. That is why London suited him so much: it was a large and very public stage on which to “characterise” himself. Even in the age of Enlightenment, Edinburgh still held fast to “Auld Licht” (“Old Light”) Protestantism—Robert Burns would name and shame it, and be punished by it—and Boswell was never entirely loved by his father, a Calvinist judge of the unforgiving sort who felt that his son, with his pretensions to freedom of expression and freedom of selfhood, was a kind of mad fool. Yet Boswell, as London expands, is a pioneering figure of the young educated man, the lad of parts, who seeks a new social existence in the modern city.

Newly arrived, Boswell takes the shape of his favorite ideas. “I have discovered,” he writes, “that we may be in some degree whatever character we choose.” He found that the capital contained a creative ether, and was hospitable then, as it still is, to the adventuring soul. Not everyone viewed the city as fertile ground for their multiplicity: Lord Shaftesbury, for instance, constantly asked himself, “Who am I?” And his answer, reports Zaretsky, shows a man perturbed and unsettled. “I [may] indeed be said to be lost,” he wrote, “or have lost My Self.” Yet when Boswell first saw St. Paul’s cathedral from Highgate Hill, he had already absorbed the best writings of Hume and Adam Smith, as well as the classics of the European Enlightenment, and was fully ready to draw fresh complications from the ancient oracle “Know Thyself.”

Zaretsky reminds us that Hume compared the self to a sort of theater, a condition that denies the possibility of a single self who predominates from within. Boswell would struggle with this—as many people do today in the digitorium of social media, playing at being too many people. One suspects that the Boswell who would have been a hit on Facebook was always trying to fight his way back to the notion of a single, authoritative personality. He fetishized Samuel Johnson as such, a total mind, a moral unity, a man who was never knowingly not himself. Boswell will always be the lovable cracked actor next to the monolithic Johnson.

Advertisement

In a sense, the Life of Samuel Johnson is not just a very great biography but a great biography of James Boswell’s style and the manner of its deployment. (With a writer, the only biography that matters, said Nabokov, is the story of his style.) Boswell inhabited his best writing self when next to his hero, and the present book shows us how his enlightenment might indeed have prepared him for that, for the understanding that one can find second and third lives as a writer, and author the great Life of another, while still being Jamie Boswell. It was never an easy matter, for Boswell cleaved to Christianity and to a fear of hell—which promises to spit-roast the inauthentic self—and an important part of his moral and stylistic education, Zaretsky informs us, came from the minister and professor of rhetoric Hugh Blair,

affirming that we are “inhabitants of earth” as well as “candidates of heaven.” These roles, he insisted, were “only different views of one consistent character.” …God alone, Blair argued, could fill the essential moral function of knowing who we are. Without this divine, merciful, and engaged spectator, we would otherwise be condemned to a world of mirrors and masks.

Yet the Boswell who is, today, the patron saint of “life writing” walks delightedly with his great friend down a hall of mirrors, some of which reflect us. As a writer, Boswell is at the same time wonderfully present and definitely absent—we think we know him and yet we feel certain that he only slenderly knows himself. This is not merely a beautiful modern trick; it comes with the intellectual territory he walked upon. And when we find him in Europe, striking out for meetings with Frederick the Great (fail!) or Rousseau (success!), we see a man finally engaged with the whole rumbustious business of his own potential selfhood. “I shall live to the end of my life,” he proclaimed to Rousseau at the end of their meeting at Môtiers.

“That, most assuredly, is what we must do,” replied the Frenchman.

If the Scottish geniuses gave him self-doubt, it wasn’t the sort that could prevent him from pressing his dubious self on the geniuses of the Continent. “I have the art to be easy and chatty,” he said of himself, more than once, and Zaretsky’s book gives a splendid account of our hero grasping the hands and shoulders of his importuned hosts, Rousseau and Voltaire. The fact that Europe’s two most famous envoys of the Enlightenment were then at war with each other seemed to have no effect on Boswell’s ambitions for himself. The maker of The Social Contract turned down his visitor’s kind request that he become Boswell’s private religious instructor, saying he was too ill and that he could only look after himself. But it was a happy occasion because it gave Boswell a story to tell and every story was a myth to him.

On his way to see Voltaire, his mind must have been crowded with all the ideas of the great man’s life. “Ideas,” writes Zaretsky,

like Voltaire the tragedian…or, more recently, the creator of Candide…. Grand ideas of more recent mint, such as Voltaire the scourge of obscurantism, the hero of the Calas affair…. Somewhere in that mix, though, was the idea, shaped by Johnson’s animosity, of Voltaire the deist.

With Voltaire Boswell kept coming back to the business of God and death—what did a life mean and what was a soul at all if they were not anchored to eternity and a chance of salvation?

Readers new to Voltaire’s magical perversity—his being a Christian who questions Christ’s benevolence; a philosophe who believes in God’s design but not in His revelation—might find it hard to work out what Boswell could learn from him. And the answer might be that, through his persistent attendance to Voltaire, Boswell learned that earth might be the only heaven we shall ever know. He didn’t believe it, but he went on to live as though he did, and in the future Johnson would become a kind of god to him, an all-too-human force of creative willpower, and London would be a kind of heaven.

Meanwhile, Boswell managed to stay the night with the sage of Ferney and not return to Geneva. The great Frenchman refused Boswell’s little traps—as Hume would—aimed at capturing him for the God of the churches, and would give no quarter to Boswell’s belief in the immortal soul. “I suffer much,” said Voltaire, “but I suffer with Patience & Resignation; not as a Christian—But as a man.” The fear of death, extinction, and all manner of encircling darkness, which chilled Boswell to the end, was clearly made worse by several of his enlightened heroes’ imperturbable acceptance of it. Of all his heroes, only Dr. Johnson, his great subject after himself, would fear death as much as he did. In that sense, the Enlightenment gave them lives to live and afterlives to dread.

Seamus Heaney once said that, although he didn’t go to church anymore, Catholicism had given him a “structure of conscience.” I was sitting with him by the grave of the great religious poet Henry Vaughn when he said this. The graves receded from the Welsh hillside where we sat and I thought of James Boswell and how religion might have done the same for him. He couldn’t let go of it because the world would have become less interesting. Life’s pleasures might have come to seem shallow without their constituent element of sin.

And so, for Boswell, who loved liberty, the primrose path of dalliance was more than a rite of passage: it was a condition. He may have been the most god-fearing libertine of his age, but Robert Zaretsky’s book has élan, and a sense of humor when it comes to showing how even Boswell’s sexual adventures were nothing if not a sudden tumescence, as it were, of his favorite ideas. The age of reason, for him, was the age of the human, and that meant girls as much as sages. His journals are so readable because they find the human thing, as Henry James might have called it, in every circumstance where a person’s reason and a person’s desires are faced with a challenge.

Boswell caroused and rioted and wrote, but whatever else he was doing, he thought. He was an embodiment of current thinking as much as any character in literature. In Italy he spent time with the antimonarchist and libertine John Wilkes, adoring his company and being appalled by half his views, and by the time he had whored his way through Rome and Naples, he was ready for a dose of virtue with Rousseau’s friend Alexandre Deleyre, an atheist. Writing to him, Boswell insisted man should

leave others to live in peace according to their fancies and let us live according to ours, happy if we can find ways to pass without boredom or sadness this earthly existence of which we understand nothing.

If there is a new political note in this, it is well-suited to his state of mind, for he was preparing to visit the Corsican freedom fighter Pasquale Paoli. It was in Corsica that Boswell began to see how men could die for the ideas that nurtured them. Liberty was not simply a happy note embedded in the songs of the Edinburgh clubs. In Paoli he saw the Enlightenment in motion, the spirit of Tacitus and Plutarch, and he learned, I believe, to be a biographer, mainly by following Paoli around the island, sniffing out anecdotes and historical facts, showing by his own talent how great minds and beautiful ideas will operate on life.