1.

Irving Howe built three careers in one heroically productive life. From his high school years in the 1930s until his death at seventy-two in 1993, he was a political activist and polemicist, angry defender of the democratic-socialist faith against old-guard Communists and New Left firebrands, and founding editor of the still-lively political quarterly Dissent. In the 1940s he began writing the generous, sharply focused literary criticism that, together with his university teaching, gave him the greatest pleasure. Many of his later essays, notably “Writing and the Holocaust,” are grave, measured, even magnificent in their comfortless density and depth. Starting in the 1950s he made himself the preserver and historian of immigrant Yiddish culture, culminating in his best-selling World of Our Fathers (1976), a book that redefined many American Jews’ sense of themselves, and inadvertently helped set the stage for American multiculturalism.

In all his careers Howe tended to write as “we,” not “I,” expressing the collective views of ancestors and contemporaries. Even his autobiography, A Margin of Hope (1982), is written largely in the first-person plural. His 1969 essay “The New York Intellectuals” (his name for a miscellaneous cast of Lionel Trilling, Meyer Schapiro, Clement Greenberg, Howe himself, and many more) presents a collective historical narrative almost universally accepted. But Howe’s collective vision of history, in his essays and in World of Our Fathers, was the most idiosyncratic thing about him, the product of a unique sense of loss and longing that drove everything he wrote.

In his later work he acknowledged that he was reshaping the past even as he did so. His 1977 essay “Strangers” was a collective memoir, based on “recollections of the experiences shared by a generation of American Jewish writers.” He first cautioned: “I will use the first person plural, though with much uneasiness, since I am aware that those for whom I claim to speak are likely to repudiate that claim and wish to provide their own fables of factuality.” Then he shed his uneasiness and wrote the rest of the essay about what “we read,” “we chose,” and “we knew.”

In an issue of American Jewish History devoted to World of Our Fathers, historians testified that the book had changed their lives, but they realized years later that its emphasis on socialist activism, its near silence about religion, amounted to a disguised autobiography. Howe always saw the immigrant past as a “brief flare of secular passion,” but he, too, came to recognize that his sense of it was shaped by private vision. His father, he said, was “for me a representative figure of the world from which I came, and I suppose a good part of World of Our Fathers is no more than an extension of what I knew about him.”

2.

When Irving Howe was born in the Bronx in 1920, his Russian-Jewish father owned a grocery store. Ten years later the store failed and the father first became a peddler, then a presser in the garment trade, while Howe’s mother worked at a sewing machine. The family moved a few miles from the West to the East Bronx, “but socially the distance was vast. We were dropping from the lower middle class to the proletarian—the most painful of all social descents.”

Everything Howe wrote was shaped by his sense that, before he was born, his parents lost the coherence of the shtetl in the bewilderments of America, that a shared community could exist only in the lost world of our fathers, or in the imaginary world of literature, A World More Attractive (a title borrowed from Trotsky), or in a future socialist world knowable only in hope. He keeps returning to moments of loss and ending that reenact the decisive Jewish experience in which “the coherence of traditional life has been shattered”:

The New York writers came toward the end of the modernist experience, just as they came at what may yet be judged the end of the radical experience, and certainly at the end of the immigrant Jewish experience.

By the time I really got to know the New York intellectuals…they were going off in many directions.

Dissent…arose out of the decomposition of the socialist movement of the thirties.

The years of my life coincided with the years of socialist defeat.

A community is releasing its experience, a generation is sliding toward extinction.

…the tradition of secular Jewishness, which, as I turned back to it, was now clearly reaching a point of historical finish.

He admired Faulkner and the conservative Southern Agrarians for their similar endurance of a wound left by a lost past.

Norman Mailer and Howe seem unlikely allies—Howe appointed Mailer to the editorial board of Dissent and printed his inflammatory essay “The White Negro”—but both were mythical thinkers at heart, Mailer with his florid myths of gods, devils, and sex, Howe with his quieter myths of a lost coherent past. Like Mailer, Howe was often aware of his own mythmaking:

Advertisement

If there ever had been a coherent group sharing a world view and doing its work together, that must have been during the first five or six years after Partisan Review established itself in 1937 as an independent anti-Stalinist organ. But perhaps that too is an illusion? Another instance of our weakness for moving the golden age farther and farther into the past?…

Movement, community, solidarity: it seems always to have been there the day before yesterday, always to have broken up only yesterday morning, always to have left the “young ones” unfortunate in not having known the great days. An unshakable myth calling upon our deepest desires….

Howe recognized his sense of the prenatal wound of Jewish exile as a consoling myth: he and his fellow intellectuals, he wrote, were “born, as we liked to flatter ourselves, with the bruises of history livid on our souls.”

Also like Mailer, Howe made conscious use of myth to give force and shape to his political work. His 1985 essay “Why Has Socialism Failed in America?” weaves a vast, convincing fabric of sociology, politics, and economics, but ends by evoking “the mythic depths of our collective imagination” to answer the question in its title: “There was never a chance for major socialist victory in this society, this culture,” because American culture is driven by Protestant myths of individuality and providence, while socialism is communal and fraternal.

Howe defended his quixotic politics, for which “there was never a chance,” in a late essay, “Two Cheers for Utopia.” He made it clear that the impossibility of his hope was essential to his commitment. In his private myth, the collective socialist spirit receded into an inaccessible future in the same way the collective life of the shtetl receded into the past. A century earlier, Karl Marx’s vision of a Communist utopia had been driven in part by a sense that ancient Greece was, Marx wrote, “the childhood of human society,” exerting an “eternal charm as an age that will never return,” that humanity must “strive to reproduce its truth on a higher plane.” Chastened by Stalin’s mass murders, untempted by revolutionary fantasy, Howe sustained a vision of democratic socialism that would reproduce on a higher plane the shtetl’s lost communal truth. In his literary criticism he could imagine even for a long-dead author an unattainable future beyond the isolating self. An episode in Little Dorrit, he said, “really belongs, as it were, to another novel, one that might have brought Dickens to a triumph of self-transcendence but was, alas, never to be written.”

Howe never doubted that our deepest desire is a collective one, a wish for a “bonding fraternity” that was “both the most yearned-for and most treacherous of twentieth-century experiences.” He thought everyone shared his wish, and he may have been the one intellectual in individualistic New York who could have written:

I suppose most human beings have a need to cluster in circles, grasp hands, and praise the warmth they generate. The hunger for community has been one of the deepest and most authentic of our century….

His wish sometimes found coarse expression. Critics described him as always hectoring fellow leftists to join coalitions.

His deepest experience of “bonding fraternity” occurred at around seventeen when he immersed himself in the Trotskyite Socialist Workers Party:

To yield oneself to the movement—really a sect, but we called it “the movement,” and out of courtesy to the past so shall I—was to take on a new identity. Never before, and surely never since, have I lived at so high, so intense a pitch, or been so absorbed in ideas beyond the smallness of self.

Intellectually he was a loyal Trotskyite. Emotionally, he was loyal to a few friends with whom he shared a “kind of male bonding”:

We’d set off at midnight, I the youngest of this unlikely half dozen. Now everything had hushed into quiet, no one was in sight. All seemed carefree in the night, away from family and politics, though some secret anxiety always remained with me that I would get home too late and have to face hysterical scenes with my parents. Our walks were best in the springtime: the nights grew cool, a fraternal expansiveness came upon us, our enemies slept, the world was ours.

Howe seems to have felt none of the anxious terror of women that drives many young men into bands of brothers. Instead, he liked to imagine bonding sororities of women: they would “come together just by themselves, like the characters in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, for searing, intimate talks, an exchange of sardonic notation.” Reviewing The Golden Notebook, he praised most its sororal talks: “One turns to them with the delight of encountering something real and fresh. My own curiosity, as a masculine outsider, was enormous.”

Advertisement

In adult life, whenever he convinced himself that he had joined a community of feeling, he relied on the evidence of things not seen. The communities he praised were always silent or implicit: the squabbling New York intellectuals shared, he said, “a tacit belief in the unity—even if a unity beyond immediate reach—of intellectual work.” Those intellectuals, he wrote, “formed, at most, a loose and unacknowledged tribe. Still, members of a tribe are likely to know one another at depths beyond language.” “They were like-minded in deep, unspoken ways.” Howe saw in Lionel Trilling a member of his intellectual tribe, but Trilling, in his private journals, thought otherwise. “Who am I,” Trilling asked, “to feel that these people are different in kind from me, and me superior?”

Howe never escaped his conviction of the inherent “smallness of self,” his sense that his own “irruptions of need, grasping, and desire” were “the gross picturings of self.” In his memoir, he recalls finding in his army years “more nuanced ways of thinking about the self; indeed, of deciding how and whether to ‘have’ one.” He emerged from childhood with a profound sense that to be Jewish was to be so deeply wounded by the loss of a collective past that it was impossible to have an autonomous self of the kind he celebrated in his eager, large-minded essays about twentieth-century non-Jewish writers: Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, George Orwell, Octavio Paz, Luigi Pirandello, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Ignazio Silone, Edith Wharton, Edmund Wilson. John Crowe Ransom was “that lovely man,” James Agee “this princely man.” Among Jewish writers, in contrast, what he most admired was “an art of the representative, an art of the group.”

He sometimes called in the same essay for both group solidarity and lonely individualism, writing, for example, that “the future quality of American culture…largely depends on the survival…of precisely the kind of dedicated group that the avant-garde has been,” but proclaiming the opposite three pages later: “The most glorious vision of the intellectual life is…the idea of a mind…ready to stand alone.”

Protestants, he said, emerged from an individualist culture; therefore they could become individuals. Jews, he insisted, could not, and he blazed in fury at any Jew who said he could. Philip Roth (less an individual than “a cultural ‘case’”), speaking in the voice of Portnoy, wants, Howe complains,

to be left alone, to be released from the claims of [Jewish] distinctiveness and the burdens of the past, so that, out of his own nothingness, he may create himself as a “human being.” Who, born a Jew in the 20th century, has been so lofty in spirit never to have shared this fantasy? But who, born a Jew in the 20th century, has been so foolish in mind as to dally with it for more than a moment?

World of Our Fathers gave readers the pleasure of “unearned nostalgia,” but the book itself was scathing against “Jewish sentimentalism” toward a past that American Jews knew nothing about. As royalties poured in, Howe was increasingly disgusted with readers who came away from the book with the pleasant sensation that the wound of Jewishness had healed and left no scar. Fiddler on the Roof outraged him by sentimentalizing the world of Sholem Aleichem—“a world of uncertainty, shifting perception, anxiety, even terror”—into “the cutest shtetl we’ve never had.”

Howe’s immunity to Jewish sentimentalism made it possible for him to insist that the wound of Jewishness was not exclusive to Jews. He saw in the hatreds and exclusions of the “negro experience” the same genocidal hatred that murdered millions of Jews. But this sane, inclusive understanding led him to the same excluding anger that he felt when he denounced Jewish writers who valued their individual selves, and he accused James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison of denying the “negro experience”—“a pain and ferocity that nothing could remove”—in the same way he accused Roth:

What, then, was the experience of a man with a black skin, what could it be in this country? How could a Negro put pen to paper, how could he so much as think or breathe, without some impulsion to protest, be it harsh or mild, political or private, released or buried?

Ellison replied that Howe, “appearing suddenly in blackface,” had ignored “an American Negro tradition which teaches one to deflect racial provocation and to master and contain pain.” Responding in turn, Howe repeated his earlier argument: inner freedom among a wounded people was immoral and incomprehensible.

With all his storied abrasiveness and aggression, Howe sometimes wrote about himself as a passive object shaped by culture, by Jewishness, by other people. His faults derive from his culture: “My grasping, greedy American soul.” Readers assume that he chose his career as a social critic:

I never thought of myself as having made a decision…. It always seemed that I had been chosen—chosen by the time I lived in…. What others think one is forms part of what one really is. I didn’t like it but I gradually became resigned.

Recalling his recovery of his Jewish origins, he refers three times to his “reconquest of Jewishness,” a famously awkward phrase that protects him from saying that Jewishness had reconquered him.

3.

Howe always insisted that “there was not the faintest chance of going back” to a lost Jewish past. In a 1946 essay, “The Lost Young Intellectual,” he generalized from his family experience without explicitly calling it his own:

Traditionally, the Jewish family has been an extraordinarily tightly-knit group…. Today, however, it is this very shelter that the Jewish intellectual has lost, this shelter which, however he may momentarily yearn for it, he knows he can never find again. Literally homeless, he has become the ultimate wanderer.

Howe had a wanderer’s contempt for other people’s “fierce attachment to ‘personal values,’” for any sense of “‘personal relations’ as the very substance and sufficient end of our existence.” His exclusion from such feelings originated, he said, in his collective experience:

To have been raised in a working-class family, especially a Jewish one, means forever to bear a streak of puritanism which, if not strong enough to keep you from sexual assertion, is strong enough to keep you from very much pleasure.

He married four times. He alludes in his memoir to the breakup of only one, blaming it partly on culture: “I was no different from all those other Americans, piling anger and anxiety onto the slender frame of ‘personal relations.’” His tribute in his autobiography to the Yiddish poets Jacob Glatstein and Eliezer Greenberg—“I loved them, I loved their words”—are his only words of love in the book.

Until the 1950s Howe was indifferent toward his Jewishness, and to the end of his life he had no good words for Jewish nationalism or Jewish religion. His seven years’ labor on World of Our Fathers, he said, was partly his belated response to Nazi genocide, but he also named other motives. After the “debacle of socialism” he began to find solidarity in a Jewish identity neither religious nor racial,

a residual “Jewishness” increasingly hard to specify, a blurred complex of habits, beliefs, and feelings. This “Jewishness” might have no fixed religious or national content, it might be helpless before the assault of believers. But there it was, that was what we had—and had to live with.

He responded to that fraternal Jewishness only when he found it in literature or among the dead. Yiddish poetry, Howe wrote, “helped me strike a truce with, and then extend a hand to, the world of my father.” Reading the poetry of Mani Leib and Moishe Leib Halpern, “I learned where I had come from and how I was likely to end.” In Jewishness as in socialism, his imagination focused on a lost past and unknowable future.

Howe wrote World of Our Fathers in a mood like that in which W.B. Yeats wrote “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory.” When Yeats brought friends together in life, they argued among themselves; now, in memory only, Yeats summons a more harmonious gathering:

But not a friend that I would bring

This night can set us quarrelling,

For all that come into my mind are dead.

Howe’s histories of the New York intellectuals portrayed them as a Greek chorus moving in unison—left in the strophe, right in the antistrophe—until the “dedicated group” disintegrated into quarrels; “I could find no sense of shared purpose.” In his reconstructed memories of his father’s world, Howe found a “bonding fraternity” like the sepia tone in an old photograph, unknown when the picture was taken, pervading it now.

The opening sentence of World of Our Fathers announces its central historical idea:

The year 1881 marks a turning point in the history of the Jews as decisive as that of 70 AD, when Titus’s legions burned the Temple at Jerusalem, or 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella decreed the expulsion from Spain.

The most decisive event in five hundred years of Jewish history was for Howe the wave of pogroms, prompted by the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, that drove thousands of Jews from Russia to America, among them Howe’s parents. T.S. Eliot was inspired by the same kind of historical fantasy when he named as the decisive event in European intellectual history the mid-seventeenth-century “dissociation of sensibility” that, he imagined, divided thought from feeling at the exact moment when his ancestors left England for America, their voluntary exile breaking his connection to a shared ancestral past in the same way that Howe’s was broken.

The most persistent thorn in Howe’s collective thinking about Russian Jews and New York intellectuals was the critic and memoirist Alfred Kazin. Howe and Kazin emerged from an almost identical Eastern European Jewish background (Kazin was born in Brooklyn five years before Howe in the Bronx); both heard the same political arguments in the City College cafeteria; both became left-wing literary critics—but they were almost mythologically opposed in their understanding of themselves.

Kazin was an Emersonian individualist who saw himself in the line of American solitaries celebrated in his first book, On Native Grounds (1942). Kazin’s lyrical memoir A Walker in the City (1951) recalled an inward childhood with no wish for “bonding fraternity.” If Howe was right about the inescapable collective effects of wounded Jewishness, Kazin could not exist. The driving motive of Howe’s essay “Strangers” seems to have been his wish to prove that, if Kazin could not be wished or rationalized away, he was irrelevant to everyone else’s experience. The essay mentioned Kazin only in a polite sentence near the end, but it began by waving away Kazin’s confident Americanism: Howe’s essay would explore, he said, the “deep, rending struggle which marked those writers who had to make, rather than merely assume, America as their native ground.”

Contra Kazin, Howe insists that “we” were alienated from the Emersonian individualist tradition, that “we” affirmed instead “a heritage of communal affections and responsibilities.” “We” were strangers in a Protestant culture: “individualism seemed a luxury or deception of the Gentile world.”

We found it hard to decipher American culture because the East European Jews had almost never encountered the kind of Christianity that flourished in America. The Christianity our fathers had known was Catholic, in Poland, or Orthodox, in Russia, and there was no reason to expect that they would grasp the ways or the extent to which Protestantism differed.

In World of Our Fathers Howe infuriated Kazin by writing, in a breathtakingly self-assured paragraph, that Kazin was wrong about his own remembered feelings. Kazin’s “affectionate stress on the Jewish sources of his [private] sensibility seem[s] mainly the judgment of retrospect,” Howe wrote, because in the 1930s “the reigning notion was quite the opposite,” a wish to break away from Jewish tradition. Howe found it intolerable even to imagine that someone who shared his background had a notion other than the “reigning” one. Yet he was quick to denounce enemies for their “fanatical disdain for the experience of others.”

In his twenties Howe worked as an assistant to both Dwight Macdonald and Hannah Arendt. He denounced (in Macdonald’s magazine Politics) Macdonald’s inward sense of absolute morality, and in 1963 he organized a “forum” on Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem that erupted into a rally of collective denunciation against her. Howe later said of the event, “Sometimes outrageous, the meeting was also urgent and afire.” Macdonald and Kazin had been among the few speakers who resisted the prevailing frenzies.

4.

A Voice Still Heard has an unfortunate title (a fancy paraphrase of “People Remember Him”) and well-chosen, wide-ranging contents. It is unrepresentative only in excluding almost entirely his attack essays against other writers; Howe included many of them in his own Selected Writings, 1950–1990 (1990).

Much of his best work is in his later books, not represented in either selection, especially his biographical Thomas Hardy (1967) and his autobiographical A Margin of Hope. In both he increasingly freed himself from collective fantasies. In the “benign months” when he was writing about Hardy, “Tess and Jude, Sue Bridehead and Michael Henchard were utterly real to me, while Dean Rusk and Herbert Marcuse seemed mere apparitions of the Zeitgeist.” He was still drawn to an imagined past, but recognized it as imaginary.

Howe was embarrassed and defensive about his late “aristocratic” tastes for the paintings of Vuillard and Bonnard and the ballets of George Balanchine, hinting at, but never naming, the joy he found in their visions of a life altogether different from his own—a seemingly innocent continuous present, unburdened by a shattered past, a debasing culture, or a demanding future. Of Balanchine’s ballets, “I liked best those…that had neither narrative overlay nor symbolic reference, but were devoted simply to configurations of movement.”

His most moving pages occur in the later chapters of his memoir, where he comes to bleak, accepting knowledge of the self-defeating motives that shaped his public career: “There was a certain irony in moving closer to the secular Yiddish milieu at the very moment it was completing its decline. Another lost cause added to my collection?” He had spent decades hectoring the young with examples from the socialist and Yiddish past. Now,

I stopped pretending that this tradition could provide answers to the questions young people asked. What I had—the fragments of a past—was enough for me, and more I could neither take nor give.

As for building a future: “Programs, perspectives? I gave up the pretense.” “Whatever evaded positions, categories, statements gleamed with a new attractiveness.”

“Past sixty,” he writes, “I think frequently about death,” about “extinction, total and endless.” But he faces it with gratitude for his losses, released at last from bravado and illusion.

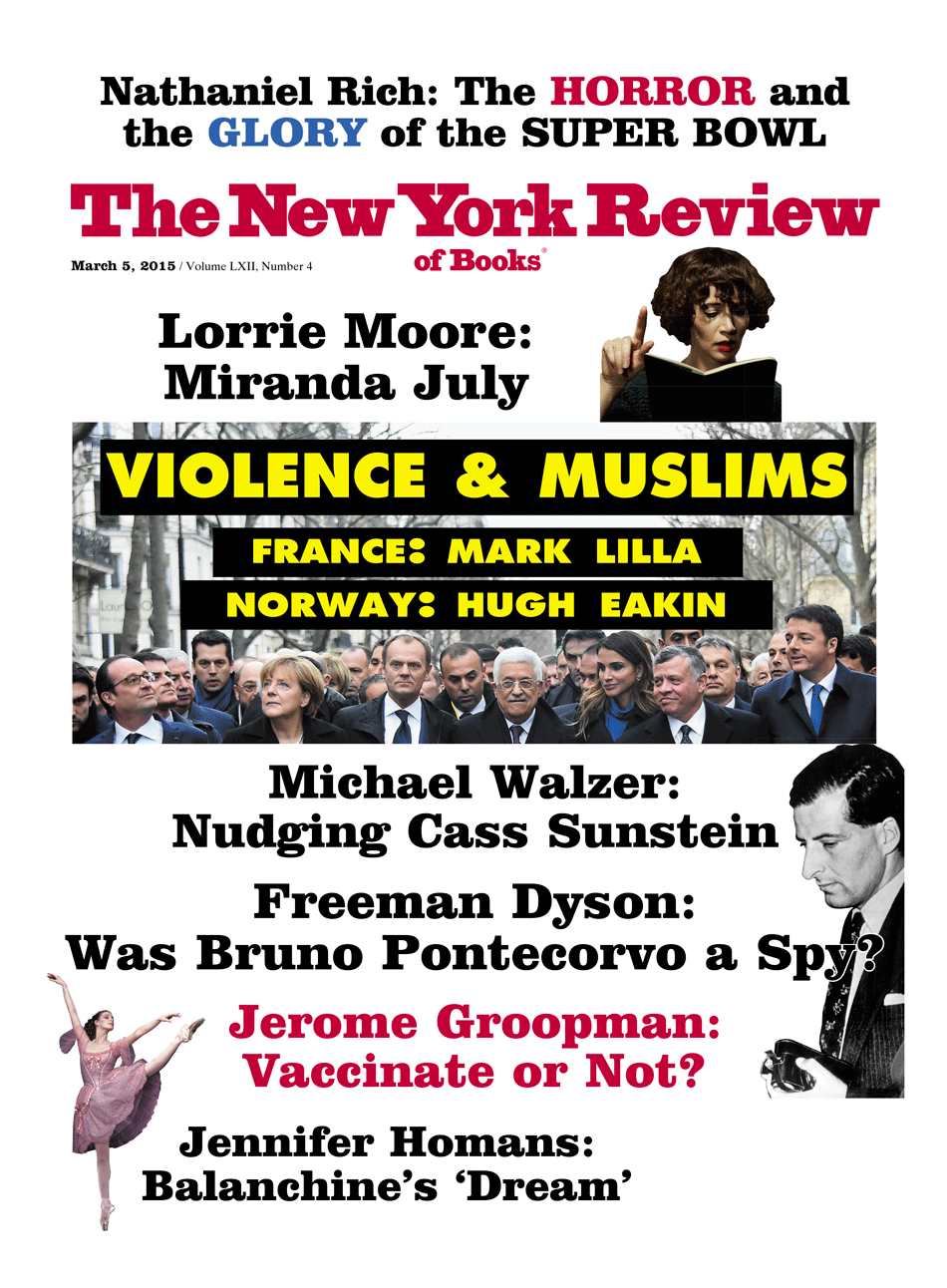

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

France on Fire