Elmore Leonard, who died two summers ago, aged eighty-seven, became famous as a crime novelist, but he didn’t like being grouped with most of the big names in that genre, people such as Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett or, indeed, any of the noir writers. He disapproved of their melodrama, their pessimism, their psychos and nymphos and fancy writing. He saw in crime no glamour or sexiness but, on the contrary, long hours and sore feet. His criminals didn’t become what they were out of any fondness for vice. They just needed work, and that’s what was available. They are not serial killers (or only one is), but bank robbers, loan sharks, bookies.

Leonard’s father worked for General Motors, and Leonard spent most of his early years in Detroit, his mind occupied mainly by sports and girls. He also liked to read: adventure books and, later, the novels that his sister received from the Book of the Month Club. (Hemingway became his idol.) After graduating from high school in 1943, he was drafted and went with the Seabees to New Guinea and the Admiralty Islands, where, he said, he mostly handed out beers and emptied garbage. Once he got back from the war, he went to the University of Detroit on the GI Bill, majoring in English and philosophy. (His entire education was acquired in Roman Catholic institutions, to which, he later said, he was very grateful, since they taught him to write a proper English sentence.) After graduation, he got a job right away, working for Campbell-Ewald, the ad agency that handled Chevrolet. But he soon came to hate advertising, and he thought he might try writing stories for magazines.

Stories about what? During Leonard’s youth, Wild West movies—My Darling Clementine, Red River—were immensely popular, and he adored them. In the 1940s and 1950s, there was also a big market for western novels and, in the magazines, for western stories. Leonard made a schedule for himself. He would get up early, go down to his basement, and, from five to seven, write stories before going to work. The third one he sent out, “Trail of the Apache” (1951), got taken by Argosy, a popular men’s magazine. In the decade that followed, Leonard sold many more stories, and several novels. A couple of the stories were also made into Hollywood films. Riding high, he quit Campbell-Ewald in 1961, hoping to become a full-time writer. But his family was growing—he and his wife eventually had five children—and he got sidetracked doing freelance jobs to make money.

Meanwhile, his market changed. In the 1960s, westerns were disappearing from both film and print. (The genre was being absorbed by TV.) Leonard’s agent, a smart woman named Marguerite Harper, told him to get out of westerns. He tried. After writing his first non-western novel, The Big Bounce (1969), he backslid and wrote two more westerns. He really did love the genre. But then he finally made the break to crime, and he stayed with it for forty-odd years.

Subject matter was only one of Leonard’s commercial considerations. More important to him, probably, was his prose style. Not just his western tales, but fully twenty-seven of his novels and stories were adapted for film or television. He said that a big reason his books sold to makers of movies and TV was that, with their natural-seeming dialogue and their open-and-shut scenes, they looked easy to shoot. But Hollywood didn’t just discover those virtues in Leonard. He developed them, at least in part, for Hollywood. After Marguerite Harper died, he moved his business to a Hollywood agent, the famous H.N. Swanson, and the Swanson Agency handled most of his work—novels, movies, TV—from then on.

The only time Leonard got jitters about writing, he said, was when, for some reason—a competing assignment, a delay in obtaining information—he couldn’t get going on the job. Once he started, he was fine. He went at it from nine to six, often skipping lunch. (He ate peanuts out of a can.) In fifty-nine years, he produced forty-five novels.

Many people would say that Leonard’s greatest gift was his “ear,” meaning, broadly, the ability to write English that, while it sounds extremely natural, is also beautiful and musical. When critics speak of a writer’s ear, this often carries a political implication, of the democratic sort. They are talking about writers (Mark Twain, Willa Cather) whose world, by virtue of being humble, would seem to exclude beauty and music, so that when the writer manages to find in it those riches, the world in question—and, by extension, the whole world—comes to seem blessed. In Glitz (1985), one of Leonard’s first truly distinguished novels, the hero, Vincent Mora, a policeman, is about to go to Puerto Rico on medical leave. He longs to make this trip. He wants to see Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, where his father shipped out in World War II:

Advertisement

He had a picture of his dad…taken at El Yunque, up in the rain forest: the picture of a salty young guy, a coxswain, his white cover one finger over his eyebrows, grinning, nothing but clouds behind him up there on the mountain: a young man Vincent had never known but who looked familiar. He was twenty years older than his dad now.

That’s because his father was killed in the Battle of Anzio, in Italy, soon after the photograph was taken.

Leonard doesn’t clobber us with this grim fact. Indeed, he tells us about the father’s death before describing the photograph. And as Mora’s mind turns to the photo, any sorrow is forgotten. It is then that we hear of the “salty young guy,” “grinning, nothing but the clouds behind him.” That last phrase would seem the culmination of happiness. He is in the sky, this lucky boy! Then we come to the next clause—“a young man Vincent had never known”—and we remember. The reason Mora’s father is in the sky is that he’s dead.

There’s another young man. The night before Mora has reason to think about his father, he is coming home from work, walking from his car to his front door, with a bag of groceries—“a half gallon of Gallo Hearty Burgundy, a bottle of prune juice and a jar of Ragú spaghetti sauce”—when he is accosted by a strung-out young mugger. Somehow he can’t bring himself to drop his jug of Gallo on the sidewalk and reach for his gun, which would have been the safe thing to do, and also the professional thing. Instead he tries to reason with the boy:

He said, “You see that car? Standard Plymouth, nothing on it, not even wheel covers?” It was a pale gray. “You think I’d go out and buy a car like that?” The guy was wired or not paying attention. “It’s a police car, asshole. Now gimme the gun and go lean against it.”

The ploy doesn’t work. The boy shoots Mora; the groceries fall; Mora, groping through the broken glass, finds his gun and fires it. He comes out okay; the mugger doesn’t. Mora, the son of a dead boy, has given the world another dead boy.

In twenty years on the police force, this is the first time he has ever killed anyone. He cannot console himself. Lying in his hospital bed, he speaks to his closest friend on the Miami Beach police, Buck Torres:

“I didn’t scare him enough,” Vincent said….

Torres said, “Scare him? That what you suppose to do?”

Vincent said, “You know what I mean. I didn’t handle it right, I let it go too far.”

Torres said, “What are you, a doctor? You want to talk to the asshole? You know how long the line would be, all the assholes out there? You didn’t kill him somebody else would have to, sooner or later.”

This is a sample of Leonard’s “ear” in the narrow sense of the term: his feel for the spoken word. Asked, once, how he was able to tap into actual speech rhythms, Leonard answered, “I just listen.” (He also tipped his hat to a few novelists he regarded as masters of dialogue, above all George V. Higgins, the author of The Friends of Eddie Coyle.) In the words he gives his characters, he often dispenses with verb-tense niceties and above all with subordinate conjunctions and the conditional and subjunctive verb forms that go with them. (“You didn’t kill him somebody else would have to.”)

In certain of his novels, these grammatical adjustments, combined with regional usage, produce something one could call dialect. Leonard’s dialogue contains great tributes to the speech of Mexican-Americans and Cuban-Americans and old Jewish men named Maury who want to tell you how much better things were in Miami in the old days. But Leonard lived almost all his life in or around Detroit, a city where, in his time, more than half of the people, and well over half of the people involved in the criminal justice system, were African-American. Consequently, a lot of his best characters are black, and speak a language that many people, black and white, would agree is classic African-American, mid-twentieth-century, northern. Early in his Unknown Man No. 89 (1977) we encounter a situation commonly found in stories about crimes committed by people working in tandem: not all the collaborators know what the take was, and some of them suspect that they’re not being given their fair share. In Unknown Man one bank robber asks another how much they got from the Wyandotte Savings job:

Advertisement

“We didn’t get nothing,” Bobby said.

Virgil nodded, very slowly. “That’s what I was afraid you were going to say. Nothing from the cashier windows?”

“Nothing,” Bobby said. “No time.”

“I heard seventeen big ones.”

“You heard shit.”

“Told to me by honest gentlemen work for the prosecuting attorney.”

“Told to you by your mama it still shit.”

Virgil then excuses himself to go to the bathroom, emerges with a twelve-gauge shotgun, and blows Bobby away.

Even more masterful than Leonard’s dialogue is his third-person point-of-view narrative, where events are narrated as if objectively but in fact are being related from a tight, though shifting, point of view. Freaky Deaky (1988), which may be the most beloved of Leonard’s novels (it was his own favorite), is dominated by a superb odd couple, Donnell Lewis and Woody Ricks. In the novel’s backstory, in the 1960s and 1970s, Donnell was a Black Panther; Woody was a rich, radical-chic sympathizer. He gave money; he opened his house for parties, as long as he could take one or two of those girls who didn’t shave their armpits upstairs to bed. Now in the 1980s, all that is over. Woody is a prostrate alcoholic—happy to be one—and Donnell, having managed to get rid of Woody’s chauffeur, cleaning lady, gardener, lawyer, and everyone else, lives with him and sees to his every need, while also trying to figure out a way to become his sole heir, soon.

In the morning, when it’s time to get up, Donnell brings Woody two vodka and ginger ales on a tray. Woody drinks one, vomits, then drinks the other one and starts to feel okay. Breakfast is cornflakes and vodka; lunch seems to be some more vodka. Then nap. Though the nap is described in the third person, Donnell is clearly speaking, or thinking:

What the man liked to do for his nap time, couple of hours before dinner: turn on the stereo way up loud enough to break windows, slide into the pool on his rubber raft naked to Ezio Pinza doing “Some Enchanted Evening” and float around a few minutes before he’d yell, “Donnell?” And Donnell, his hand ready on the button, would shut off the stereo. Like that, Ezio Pinza telling the man to make somebody his own or all through his lifetime he would dream all alone, and then dead silence. No sound at all in the dim swimming pool house, steam hanging over the water, steam rising from the pile of white flesh on the raft, like it was cooking.

Out of Donnell’s combined fastidiousness (“steam rising from the pile of white flesh”), wonderment (“Ezio Pinza telling the man to make somebody his own”), and guile, Leonard creates this marvelous character. In the novel there are also two unsavory former radicals who are planning to extort money from Woody by threatening to blow up his house. And there is a police detective, Mankowski, from the bomb squad. (He’s the hero, at least officially.) The point-of-view mike gets handed around among these people, each supplying his own accents, his own details, scores of them, every one of them perfect for that character, and also perfect just in itself, in its accuracy, its solidity.

In 1981 a fan of Leonard’s, Gregg Sutter, began doing research for him; eventually he went to work for him full-time. Sutter is editing the Library of America’s three-volume set of Leonard’s work. The second volume was just published. Each volume ends with an invaluable twenty-eight-page chronology—almost a biography—and Sutter is at work on a full-scale biography. It is no doubt owing to him that I now know how to open a metal door locked by a deadbolt, where to shoot an alligator (right behind the skull) if I mean to kill it, and how to obtain financing for a movie. Indeed, I believe I could steal a car.

Leonard had a taste for the grotesque, for an almost magical ugliness. Apart from Detroit, his favorite setting was South Florida (he had a condo in North Palm Beach), and that area offered him a lot of vivid material: a drug culture, a flavorful ethnic mix, shirts with hibiscus prints. In one Florida novel, LaBrava (1983), a Cuban immigrant named Cundo Rey—car thief by day, go-go dancer by night—tells a man who is trying to eat lunch how he once saw a snake digesting a bat. As he watched this, Cundo says, one of the bat’s wings was still sticking out of the snake’s jaws, and moving. I don’t understand how that’s possible, but I’ll see it till I die: a bat’s wing, or maybe just the tip, feebly moving for a few minutes more, while, as Cundo enthusiastically explains, the other end of the animal is “down in the snake turning to juice.”

In another Florida tale, Stick (1983), we are told what it’s like for a drug importer, Chucky, when his daily Quaalude regimen is interrupted: “He felt exactly the way he had felt when he was twelve years old and had killed the dog with his hands.” That sentence is all we hear about the dog until fifty pages later, when we get one more sentence, informing us that after Chucky choked the little thing—it was annoying him—he threw it against a brick wall.

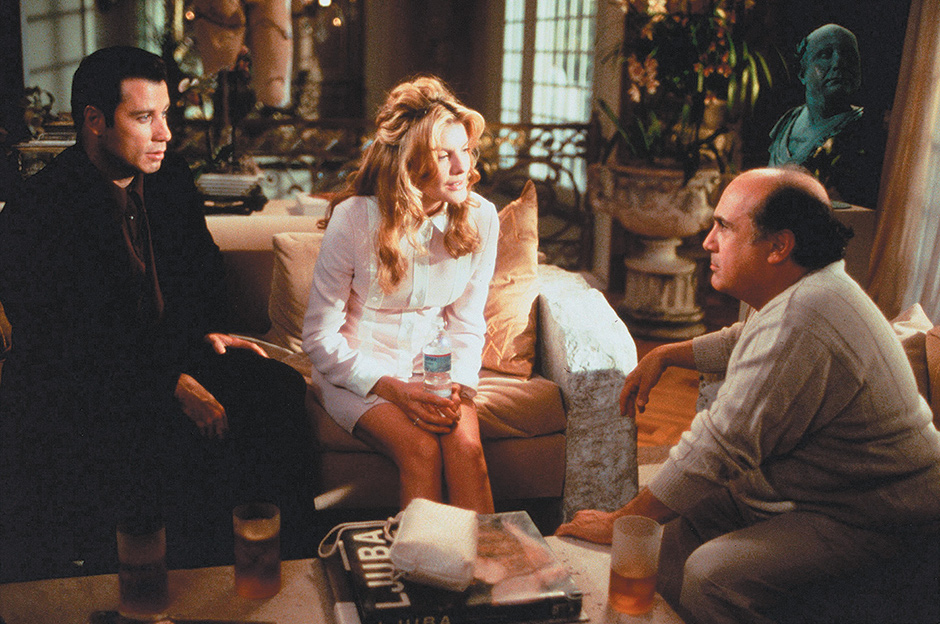

But whatever his fondness for the elaborately horrible, Leonard’s books are sometimes surprisingly short on ordinary violence. Chili Palmer, the loan shark hero of Get Shorty (1990)—he is probably Leonard’s most beloved character (he was played by John Travolta in the movie, and that no doubt helped)—doesn’t carry a weapon. Violence is bad for business, he says. When there is violence, even murder, it is often hedged in by so many confusing and ridiculous circumstances that it no longer feels violent. In Maximum Bob (1991), a Florida novel, we get the following: “When Roland was shot dead and Elvin sent to prison for killing a man he thought was the one had got the woman to kill Roland, nobody in the family seemed surprised.” By the time you get to the end of that sentence, you’re not surprised either. Makes sense.

This may have less to do with Leonard’s ethics than with his aesthetics. He just wasn’t that interested in his plots, and the reason, he explained, was that he was too interested in his characters, above all the bad guys. In his mind, he said, “I see convicts sitting around talking about a baseball game. I see them as kids. All villains have mothers.” Indeed, he was their mother. He picked out their clothes; he chose their names. (He was a champion namer—this was part of his “ear”: Mr. Woody, Jackie Garbo, Chili Palmer, Cundo Rey. One thug has a tiny little daughter named Farrah.) He gave them girlfriends, ways of speaking, things they liked to eat. And as they were flowering under the beam of his affection—riding around in their stolen cars, discussing their upcoming felonies—he tended to ignore the noncriminal element in his books: the police, the decent citizens, the people who might push the plot forward by preventing or solving the crimes. Regular people, he complained, “don’t talk with any certain sound.”

The resulting story lines may, in the words of Ben Yagoda of The New York Times, come to seem like “smoky improvisations.” Eventually, Yagoda said, “the elements congeal into a taut climax, but for the first two-thirds or so of the book, the characters, the reader and, it turns out, the author simmer on the low burner and, in Huckleberry Finn style, ‘swap juices,’ trying to figure out what’s going on.” This isn’t true of all Leonard’s novels—he created some masterful farce plots—but it’s true of many of them, especially the better ones. Leonard thought writing was fun. (That’s how he could do it from nine to six, five days a week.) And he kept it fun by not forcing himself to do what he didn’t want to do, such as construct tidy plots. It should be added that his plots, however meandering, do not usually make him hard to read. Glitz, the book that inspired Yagoda’s remarks, above, spent sixteen weeks on the Times best-seller list, and from that point on, every last one of Leonard’s novels was a best seller. He wasn’t the only person having fun.

As for the quality of the writing, his career follows a neat bell curve. This is not usually the case with artists whom we consider first-rate. Very many of them have finished doing their best work by age sixty. Leonard started doing his best work at age sixty. You can see his earliest efforts in the just-published Charlie Martz and Other Stories, a file-cabinet-clean-out collection, with a foreword by Leonard’s son Peter. These are the stories that Leonard pulled out of himself in the basement before going to work at the ad agency in the 1950s, and they are touching, because even though most of them didn’t find publishers, they show you Leonard growing, page by page—getting over the need to be cool, breathing life into the dialogue, giving the characters little tweaks that make them singular, memorable.

The collection covers about ten years. Multiply that by three, and you have something like the first thirty years of Leonard’s novel-writing career, consisting of twenty-two books. Some were duds, and he probably knew this, but he kept going. (For one thing, the duds still made money. Crime fiction sells.) Slowly, slowly, he got better, and even slow betterment, if it goes on for thirty years, adds up to serious improvement.

In the early 1980s, something changes. His plots, auspiciously, become messier, and his characters, as if electroshocked, come to full, breathing life. In the eleven years from 1985 to 1996, he produces his five best novels: Glitz, with Vincent Mora and the father in the sky; Freaky Deaky, with Mr. Woody on the raft; Get Shorty, with Chili Palmer; Maximum Bob, with Elvin killing the man he thought was the one had got the woman to kill Roland; and Out of Sight (1996), whose hero has robbed over two hundred banks. Then, quite smoothly, Leonard passes the apex and begins to decline. Once more, he must have known; once more, this did not stop him.

Most of the critics said nothing, either out of deference to his age or because by then he was not just a writer but a symbol of that cluster of virtues—virility, stoicism, plainspokenness—that are supposedly central to American art, and constitute our bulwark against its takeover by the snobs and the fancy-pants. Such caricatures are routinely drawn of aging artists, partly in defense against anticipated criticisms of their now-weakening product. It is hard for an artist over seventy to get an honest review. Leonard was seventy when Out of Sight was published. He wrote thirteen more novels. All of them were overpraised.

But their predecessors weren’t. Part of the reason genre art is held in lower esteem than other art is that it hews to a formula and thereby gives artist and audience less work to do—indeed, less work they can do. If, for example, a crime novelist takes on love or hope or the loss of hope, there is a limit to how subtle and fresh his thoughts about such things can be, because if he gets too interesting, he might violate the formula. But in Out of Sight, Leonard’s masterpiece, he takes on exactly those three subjects, and gives them a tender new life. Jack Foley, the veteran bank robber, has no interest in changing his line of work. The day after he escapes from prison—the book begins with the jail break—he holds up another bank. “Fell off your horse and got right back on,” his partner, Buddy, says to him.

But in the middle of the escape, something happens to him. Outside the prison yard, he runs into a good-looking twenty-nine-year-old deputy federal marshal, Karen Sisco, carrying a pump-action shotgun. She is there on some other business, but she immediately realizes what Foley is up to and tells him he’s under arrest, whereupon he pushes her into the trunk of her car, climbs in after her, and pulls down the lid. Buddy gets behind the wheel, and off they go.

Foley and Karen spend about ten pages in the trunk together—after the initial awkwardness, they talk about movies (“Another one Faye Dunaway was in I liked, Three Days of the Condor”)—and Foley falls in love. So, probably, does Karen, though soon afterward, when they are switching cars, she tries to shoot him. (She takes her job seriously.) Later, as Foley is mooning over her, Buddy tells him he’s too old (forty-seven), and has too long a rap sheet, to think about having a woman like that: “The best either of us can do is look at nice pretty girls and think, well, if we had done it different…”

The remaining chapters are devoted to finding out whether that’s true. At points, Out of Sight is throbbingly romantic. (Foley and Karen get a single night together, after having drinks in one of those glass-walled revolving cocktail lounges, in a snowstorm.) The book is also, for Leonard, extremely violent. At the same time, strangely, it is one of the author’s funniest books. It ends as we knew it would. Not only does Foley not get the girl; she finally succeeds in arresting him. He asks her to kill him. He can’t bear to go back to prison. She shoots him, but only in the leg, to prevent him from escaping. She then goes up the stairs to where he has fallen and lifts his ski mask:

“I’m sorry, Jack, but I can’t shoot you.”

“You just did, for Christ’s sake.”

“You know what I mean.” She said, “I want you to know…I never for a minute felt you were too old for me.” She said, “I’m afraid, though, thirty years from now I’ll feel different about it. I’m sorry, Jack, I really am.”

It’s a cold ending—Hollywood couldn’t bear it; they changed it—but it’s warmly cold. Before this, there was love, and comedy. They’re still there, and so the sadness is greater: lacrimae rerum. Not all of Leonard’s books are on this level, but five or six of them are, plus parts of many others. That’s a great deal.

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump