Nicolas Nabokov was a Russian composer, exiled at sixteen, a year and a half after the October Revolution, and best known for his career as secretary-general of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an international organization created in 1950 for the purpose of sponsoring festivals, conferences, and magazines that would exemplify Western artistic and intellectual freedom in contrast with Soviet censorship and conformity. Nabokov brought unique gifts of energy and generosity to the job. Working for the congress—often working against his bureaucratic colleagues—he conceived and organized the first large-scale international festival of music, drama, and the arts, a far more complex and ambitious affair than pre-war local festivals like those presented at Salzburg or Glyndebourne. He opened everything he organized to composers and artists who worked in every contemporary style, including those he privately disliked. He sustained lifelong friendships in four languages, and was loved and admired by friends as various as Isaiah Berlin, George Kennan, Mary McCarthy, Leontyne Price, Igor Stravinsky, and W.H. Auden.

Then, in the 1960s, the Congress for Cultural Freedom was revealed to have been funded secretly by the CIA, and for the next fifty years received wisdom has judged everyone involved as either a willing agent or an unwilling dupe of American imperialism. Vincent Giroud’s nuanced and scrupulously documented Nicolas Nabokov overturns that judgment, and brings into clearer focus a contentious episode in cold war history. Its deeper implications include new ways of thinking about the psychology of exile and its effect on twentieth-century art and culture.

Nabokov’s first cousin Vladimir Nabokov, born four years before him, was also exiled in adolescence, but the two responded to exile in diametrically opposed ways, each choosing a different life path, like brothers in a timeless myth. Exiled at an age when adolescents typically construct their personality from a combination of their inner impulses and the norms and conventions of their surrounding culture, each was forced to create himself in his own way, in the sudden absence of the culture that had sustained them in childhood.

1.

Nicolas Nabokov was born in 1903 to a family of wealthy liberal intellectuals. He spoke Russian to his father, French to his mother, English to one governess, and German to another. One day he had his “first musical shock” when he heard his mother play a Rachmaninov prelude on the piano, and he resolved to be a musician. Later, looking back to his childhood, as Giroud reports,

what remained in Nabokov’s memory was a prelapsarian universe, in which music took possession of him—as he saw it—not through dry piano exercises, but naturally, through the “open window” which let him absorb the sounds, smells, and rhythms of the surrounding world.

After his family fled the revolution, Nabokov studied music in Germany and France, paying his way with private lessons in music and languages and with music reviews for a Russian émigré newspaper. As his own compositions began to be performed, he found his way into social circles as varied as Count Harry Kessler’s louche entourage and Jacques Maritain’s spiritual devotees. Sergei Diaghilev commissioned Nabokov’s first ballet, Ode, for the Ballets Russes when he was twenty-five. Looking for work during the Depression, he got himself invited to America by Albert C. Barnes to lecture at the Barnes Foundation, then, at thirty-three, began his first regular academic job at Wells College in upstate New York in 1936.

At Wells he got his start as an impresario by organizing student productions of Oedipus the King, Samson Agonistes, Androcles and the Lion, and The Tempest with choruses and incidental music that he composed for the occasion. “It was an admirable collective effort,” he wrote later, “the closest I had come to see the workings of a true ‘commune,’ although none of us dreamt of calling it that way.”

He enjoyed his work at Wells but felt restless in its provincial isolation. So in 1941 he left for St. John’s College in Annapolis; while there he spent much of his time in cosmopolitan Washington, though he also organized a student choir and an orchestra comprised of students and local musicians. His teaching methods—and his insistence on organizing a schedule-disrupting student production of The Tempest—provoked conflicts with the college authorities, and for the rest of his life he continued to annoy bureaucrats with his artistic and intellectual passions.

He had been attracted to St. John’s by its “great books” program, which seemed to embody something resembling the devotion to literature and art that he had enjoyed at home in Russia. But he soon questioned the curriculum of exactly one hundred books (“a straight-jacket for the mind”) and the Socratic method prescribed for teaching them. The Socratic method, he found, can teach students to recognize their own ignorance but can be worse than useless for teaching them anything else; in practice, it leaves them trapped in the teacher’s preconceptions. When the college dean ordered Nabokov to use the Socratic method to teach music, a subject about which his students already knew they knew nothing, Nabokov forced a confrontation in his classroom that left the dean humiliated.

Advertisement

In 1940, by “an accident of fate,” Nabokov met the young diplomat Charles Bohlen, who had worked in the American embassy in Moscow. Bohlen brought him into a circle of diplomats, led by George Kennan, who later did much to shape American cold war policy. In the last months of World War II, W.H. Auden insisted that Nabokov join him in the US Strategic Bombing Survey, a quasi-military unit that was studying the effect of Allied bombing on civilian morale. This brought Nabokov to occupied Germany, where he later found work in a branch of military government that controlled German theater, music, and film. Back in America in the late 1940s, with an increasing sense that he was morally obliged to work against all forms of totalitarianism, he allied himself with the anti-Communist left, writing essays on music and politics for Partisan Review and Dwight Macdonald’s magazine Politics and working with Mary McCarthy to set up exchanges between liberals in Europe and America.

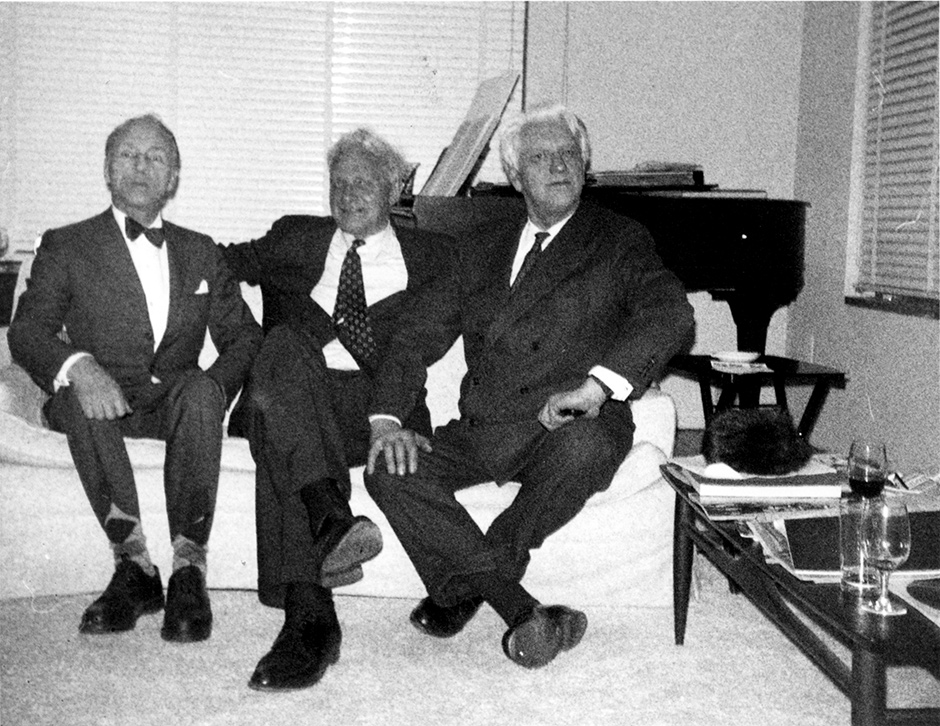

An international conference on the arts in Berlin in 1950 led to the creation of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, based in Paris, with an unimpeachable list of honorary chairmen that included Benedetto Croce, John Dewey, Karl Jaspers, Bertrand Russell, and Jacques Maritain. Nabokov’s diplomatic and artistic record made him the obvious choice to lead the congress, and for the next fifteen years he reigned, in Stravinsky’s phrase, as “culture generalissimo” of the non-Communist West.

2.

Nabokov’s personality, and the style of his music, had by now taken shape. He was gregarious, expansive, alert to the style and manner of everyone around him, “a superb mimic, in at least four languages” (said George Kennan), “an irresistible source of torrential wit and fancy, immensely sociable” (said Isaiah Berlin). He responded to exile by opening himself as a focus of warmth and welcome, so rich in words and energy that only a few friends seem to have noticed the wound inflicted by his exile, the absence of something central, deep within himself.

His intellectual integrity was passionate and unwavering, but his relations with others, though extravagantly generous, seldom seemed to have had the intimacy made possible by a focused, cohesive selfhood—what Virginia Woolf called in Mrs. Dalloway “something central which permeated.” He said of himself in his late book of stories and recollections, Bagázh: Memoirs of a Russian Cosmopolitan (1975), “as Ariel says, my wish was and is ‘to please.’” In his book, he describes himself and his friends in the broad strokes of a friendly caricaturist or raconteur. Everyone, including himself, lives on the surface; no one shows the outer signs of an inner life.

One of the elements that seems to have held Nabokov’s personality together—and gave force to his intellectual integrity—was the contrast he remembered from childhood between two styles of Russian Orthodox church music, the “cheap adaptations of popular tunes from Italian opera” sung at most services (Giroud’s description) and the “authentic Russian chant traditions” heard only at Christmas and Easter. Nabokov’s early aesthetic judgment between right and wrong kinds of music grew into his adult moral judgment between right and wrong ways of thinking about culture and politics.

The few available recordings of his music, and Giroud’s reports of other works, suggest that his style combined an underlying late-Romantic Russian lyricism with surface details chosen from an eclectic range of sources. His ballet Don Quixote (1965), commissioned by George Balanchine, opens in twelve-tone style, then proceeds in the manner of the great Russian ballets, inflected with brief echoes from seventeenth-century composers and Stravinsky, the composer whom he most revered. Stravinsky, too, evoked four centuries of musical style, but chose a single ancient or modern style to echo in a single work, while Nabokov combined in one work as many as a dozen different styles. Nabokov’s most intense and personal works (at least among those I have heard) are his least eclectic, notably his 1966 settings, in a modern Russian style, of lyrics from Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem, poems of loss provoked by Stalinist terror.1

Witold Gombrowicz, who liked Nabokov without being dazzled by his charm, wrote what he called a “psychoanalysis” of the “cynical, lyrical aspects” of his character and art:

The difficulty comes from your being an amalgam: you are never “within” something, but always “in between.” For example, you are between the spirit and the senses; between East (Russia) and West (Paris-Rome); between music and the theater; between music and words; between culture and primitivism; between art and life, etc., and there always is something in you that is a pretext for something else….

Now, it seems to me that this antinomic structure of your personality, which condemns you to be in between realities, cultures, and styles, is basically contrary to the trends (now fashionable) toward the “purified” and the abstract. But your situation may well be far richer in possibilities.

Of Nabokov’s opera Rasputin’s End (1959), Gombrowicz wrote: “One feels you are so close to your doomed hero by some kind of underground demagogy.”

Advertisement

Nabokov’s erotic life, until he was around sixty, seems, from Giroud’s account, to have had the same promiscuous generosity as his friendships. He married five times; his first three wives seem to have been as uninterested in monogamy as he was, and two stayed on friendly terms with him for the rest of their lives. Giroud reports recurring sequences of marriages, affairs, depressions, divorces, and more affairs. In Bagázh Nabokov calls himself “an inveterate (but consecutive) polygamist”; he dedicated the book to his fifth wife, with whom he seems at last to have turned monogamous.

The obscure absence at the center of himself seems to have been linked both to his good-natured polygamy and his recurring depressions that made so deep a contrast with the “light and laughter in a dark age” that gave pleasure to his friends. Giroud briefly records Nabokov’s depressions without describing them, but they seem at times to have been episodes of chaos and melodrama. Stephen Spender, who wrote the libretto for Rasputin’s End, told of a working visit to Nabokov when he “swept all the food and the cutlery off the table in front of him and buried his head in his arms. Glasses and porcelain lay broken around his feet, but he paid no attention. He was weeping uncontrollably.”2

Meanwhile, his cousin Vladimir had responded to exile and the loss of a surrounding culture by constructing an entirely different kind of personality, one that was inward, autonomous, and sharply focused on a vision of beauty remembered from his Russian adolescence. (The cousins collaborated once, on a musical setting of a lyric by Pushkin that Vladimir translated into English.) While Nicolas was pursuing his many affairs, Vladimir remained intensely attached to his wife, Véra (despite at least one affair in the 1930s). Nicolas recreated through his festival-organizing and his music the shared artistic culture of his childhood—Giroud reproduces a group portrait of Nicolas and his siblings as a string quartet—while Vladimir found perfection and beauty in the solitary act of writing and the inhuman world of butterflies.

Critics admire the aesthetic perfection of Vladimir’s novels but tend to neglect their moral and psychological genius. Vladimir’s two greatest books are warnings to himself, studies in the price he would have paid had he tried (somewhat as his cousin Nicolas had tried) to make real in his present-day life the vision of beauty he had seen long ago in Russia. Lolita tells the story of a polyglot émigré who embraces what he takes to be an embodiment of his lost youthful vision in the person of an adolescent American girl. As Humbert Humbert recalls only once (the point needs to be made only once), the result is “her sobs in the night—every night, every night—the moment I feigned sleep.” Pale Fire records the madness that another polyglot émigré, Charles Kinbote, sinks into when he finds in a poem written by an American, in the style of Robert Frost, a secret allegory of Kinbote’s banishment from the distant, possibly imaginary, country where he had once been king. For Kinbote, whose real name may or may not be Vseslav, a work of art made in the West, which says nothing about the East, can become (as if performed at some international festival) a weapon in his private campaign to regain his eastern kingdom from its usurpers.

3.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom was funded from the start with money from the CIA funneled through a foundation created for the purpose under the nominal control of Julius (“Junkie”) Fleischmann, a millionaire who had worked in naval intelligence. Whoever chose Fleischmann for this role may have had an unconscious wish to signal something fishy about the Farfield Foundation and its munificence, because Fleischmann was notoriously and exaggeratedly stingy.

The congress quickly established offices in more than thirty countries and was most visible through its influential and intellectually distinguished magazines: Encounter in Britain, Preuves in France, Quadrant in Australia, and Cuadernos published in Paris for a Latin American readership. Der Monat in Germany was allied with the congress but not officially associated with it, having been begun a few years earlier by Melvin Lasky, an ex-Trotskyite—“clever, devious philistine,” Stephen Spender wrote—who was one of the CIA-connected founders of the congress and was later, with Spender, a coeditor of Encounter. Spender made Encounter’s pages about literature and the arts lively and inclusive, while his coeditors, first Irving Kristol, then Lasky, followed a strong anti-Communist line in its pages about politics, which seldom criticized American policy.

Rumors and suspicions about the congress’s funding began early. In 1955 William Empson was writing furious letters to and about Encounter denouncing it as an organ of American propaganda pretending to be British. Lasky and the congress’s “administrative secretary” Michael Josselson took orders from the CIA, but kept assuring Spender and Nabokov that the rumors and accusations were untrue.

Giroud draws no conclusion about the extent of Nabokov’s knowledge of the congress’s funding, but he reports many episodes in which Nabokov got into disputes with his CIA-connected colleagues about festivals he was organizing in Europe and Asia. Nabokov typically wanted to invite Eastern European composers and musicians in the hope of encouraging anyone who might deviate from the Communist Party’s socialist-realist line. His colleagues insisted on maintaining ideological purity by excluding everyone on the far side of the Iron Curtain.

Around 1960 Nabokov became increasingly aware of the congress’s connections with the CIA and began to distance himself from it, partly by taking on an exhausting second job as director of the Berlin Festival, which he reorganized and expanded. When the funding scandal broke, in a sequence of partial disclosures that began in 1962 and culminated in 1966 in a series of articles in The New York Times, Nabokov and Spender were widely criticized in literary gossip and the press, first for having worked for the congress, then for their oversimplifying public denials that they knew about its funding.

The psychological reality—invisible in press reports—seems to have been that both were likely to have been aware that the money came from a source that had a clear geopolitical agenda (although Spender’s son Matthew concludes in a new book that his father had been the CIA’s “dupe”). Both firmly believed the funds were being used for a good purpose and both also had the quality that Gombrowicz noted in Nabokov of carrying on “between realities.” They had strong reasons to work against the Soviet Union, Spender having long since repented his brief youthful membership in the Communist Party of Great Britain.

The CIA made use of the writers, musicians, directors, and artists who contributed to the congress’s magazines and performed in its festivals, and evidently assumed it was using Nabokov to further its agenda. But to the degree that Nabokov was aware of where the money came from, he seems likely to have thought of himself as using the CIA, or whoever was behind the Farfield Foundation, to carry out his own artistic ideals. As Spender observed (as recalled by his son), Nabokov was “hard to control, for his feud with Soviet Russia, and with [Soviet] Russian music, was personal”—but it was not a quest for revenge. “Nicky wasn’t mourning a lost society that had pampered the Nabokov family. He was a fighter for a civilization that had been violently destroyed.”

Nabokov later said that the whole apparatus of secrecy had been pointless and self-defeating from the start. The British Council and the Alliance Française, he pointed out, publicly and without embarrassment did what the CIA chose to do clandestinely. Commenting in the 1960s on the Berlin conference of 1950 that gave rise to the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Nabokov wrote one of the most telling comments on the entire affair:

Had the American government then had the courage and foresight to establish a worldwide fund out of “counterpart currencies” to subsidize legally and overtly—as did the Marshall Plan in the domain of economic reconstruction—the indispensable anti-Stalinist, anti-Communist, and, in general, anti-totalitarian cultural activities of the Cold War, the whole ugly mess of 1966…would not have taken place.

Giroud writes that after the secret funding was disclosed Nabokov’s position “was that introducing an element of deceit in the intellectual arena, where truth and honesty should be paramount, had resulted in compromising the very cause that was being fought for.”

George Kennan put a different face on the matter. “The flap about CIA money was quite unwarranted,” he told a friend. “I never felt the slightest pangs of conscience about it…. This country has no ministry of culture, and CIA was obliged to do what it could to try to fill the gap.”

The arts have always had vexed relations with the money that pays for them. The cash that built the museum, the concert hall, the ballet theater, the university campus, was probably the fruit of cruelty, exploitation, and theft, but the blood and dirt was laundered out of it from one generation to the next until it smelled sweet. Everyone agrees to ask no questions about its past; the audience represses its guilt about the ugly source of its refined pleasures. The pious horror that erupts when incompletely laundered money is revealed to have paid for something elegant and beautiful is the return of the repressed. The horrified furiously project their hidden guilt onto a conveniently visible offender. Civilization may or may not require sexual repression, as Freud insisted it does, but it often seems to require repression of knowledge of where the money comes from.

4.

Vincent Giroud’s biography of Nabokov is lucid, readable, and judiciously affectionate toward its subject, though sometimes exasperated with his bad memory for dates. The notes quietly document errors in earlier scholarship, and the book avoids speculation where documents are lacking.

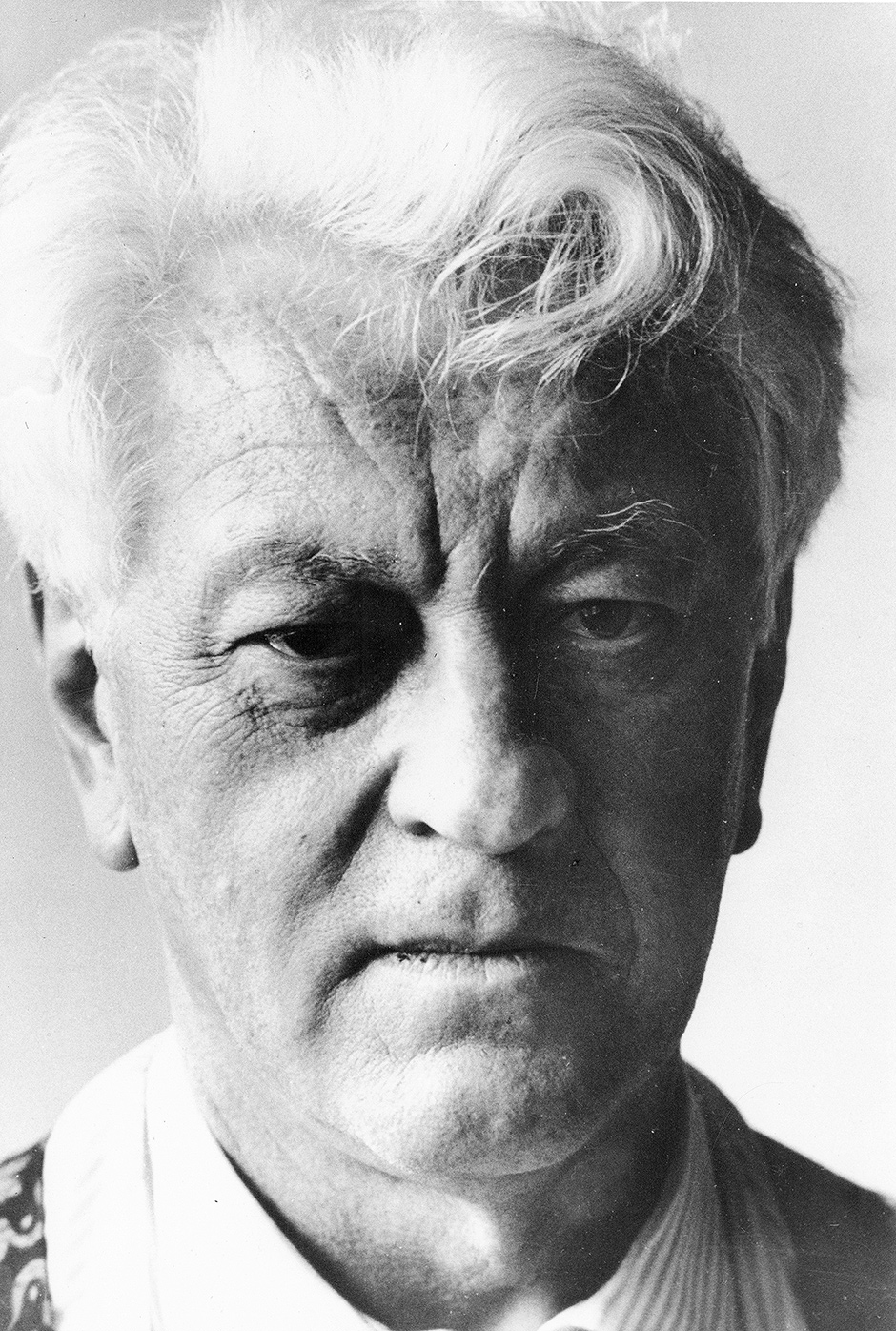

Giroud says little about Nabokov’s emotional response to the 1966 scandal over the CIA, but his book leaves openings for reading between the lines. Nabokov seems to have experienced something like the feelings that Spender privately reported to friends about his own experience of the scandal. The only person, Spender said, who had fully supported him at the time was his wife Natasha, and whatever temptations he might sometimes feel, he could never leave her. Nabokov, when the crisis occurred, had been living for two years with Dominique Cibiel, a talented young French photographer, later his fifth wife (her portraits of writers appear frequently in these pages), and he seems to have abandoned what he called his consecutive polygamy during the twelve years he spent with her afterward, until his death in 1978.

Auden remarked of Nabokov at the time he was working for the congress that he had not fulfilled his talents because “he cannot bear to be long enough alone.” Now that Nabokov had left public life, Auden—characteristically masking sympathy with brusqueness—pressured him into composing an opera based on Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost for which Auden and Chester Kallman wrote the libretto. Auden seems to have used Shakespeare’s plot as a gently instructive allegory of Nabokov’s career and the direction Auden thought it should now take: as the opera begins, the king and his courtiers hope to build an enlightened community, but they are distracted by love until, at the end, a sudden revelation of mortality startles them into a year of voluntary, contemplative solitude. Nabokov composed the opera in a mood of “continuous pleasure,” undistracted by the task of getting other people’s music performed at festivals.

In the years after the premiere of Love’s Labor’s Lost in 1973 Nabokov finally completed his memoirs, and found time to make frequent journeys to Jerusalem, “the only city I really love.” In his last years he was, with unexpected serenity, becoming himself.

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump

-

1

They may be heard online at www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSRsCqIlKN4. ↩

-

2

Matthew Spender, A House in St. John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents, to be published later this year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ↩