There has never been a better year to look at the work of Kazimir Malevich, a pioneer of abstract art often seen as the greatest Russian painter of the twentieth century. “Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art,” first shown in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and now at London’s Tate Modern, is the most comprehensive exhibition of his work ever.

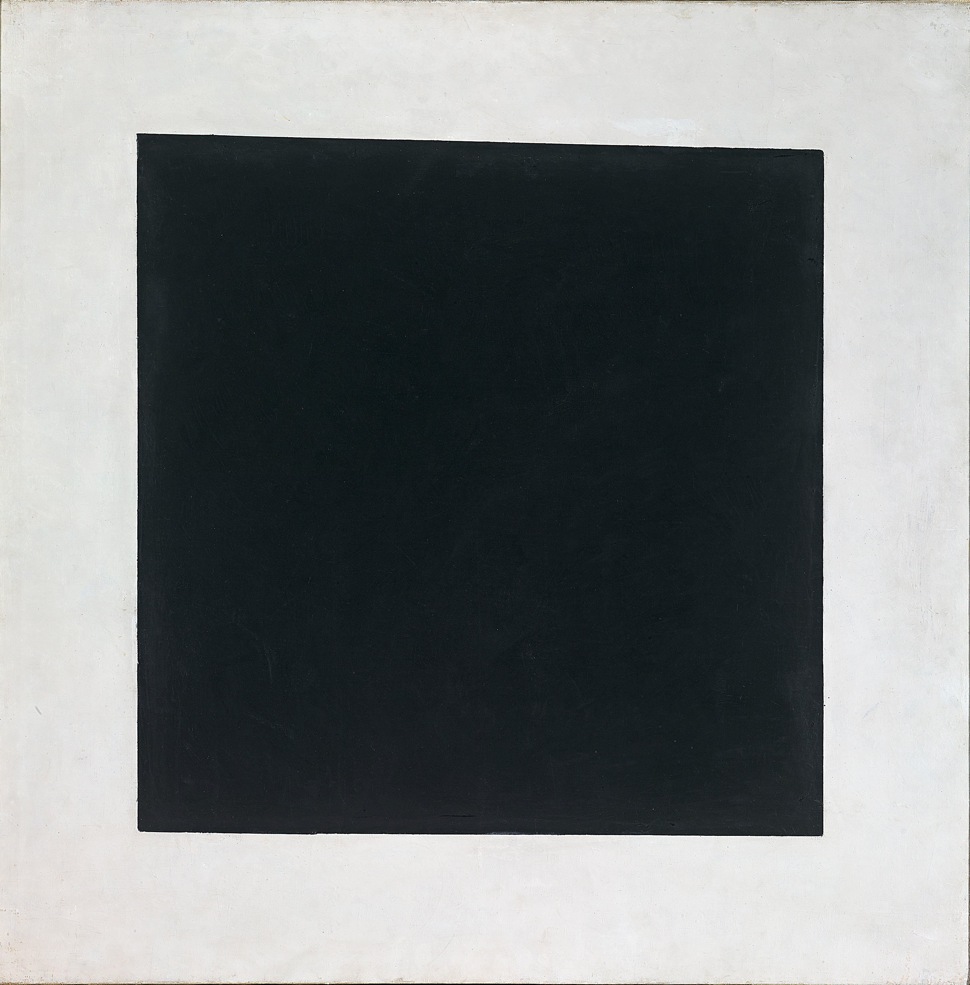

Malevich is known above all for his Black Square (1915)—a black square surrounded by a margin of white—the most prominent of the abstract, geometric paintings he called Suprematist, first shown at the now famous “0.10” exhibition in Petrograd in 1915. With Suprematism, Malevich hoped to create “a world in which man experiences totality with nature,” though using forms “which have nothing in common with nature.” He declared the Black Square to be the “zero of form,” claiming that it eclipsed all previous art. This iconoclastic icon was first shown hanging diagonally across the corner of a room, the traditional place for the most sacred icon of all.

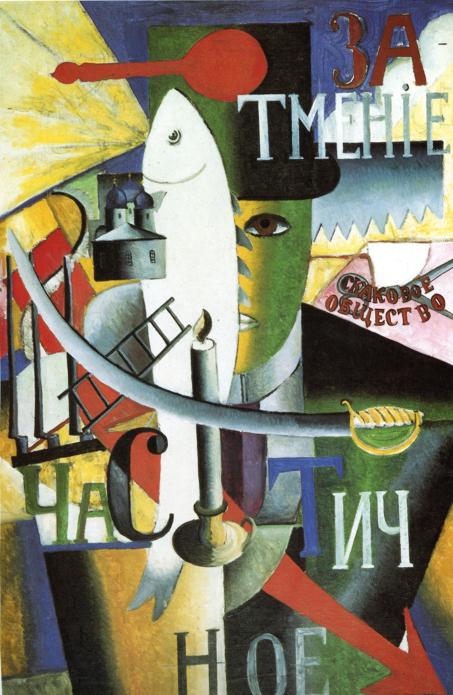

The Black Square, however, loses little in reproduction—and what we see at the Tate, in any case, is a later version, executed in 1923. What matters more is that this exhibition offers us the chance to see both Malevich’s early work—in styles that include Fauvism, what he called Cubo-Futurism, and the Dada-like style he called Alogism—and the figurative paintings of his later years.

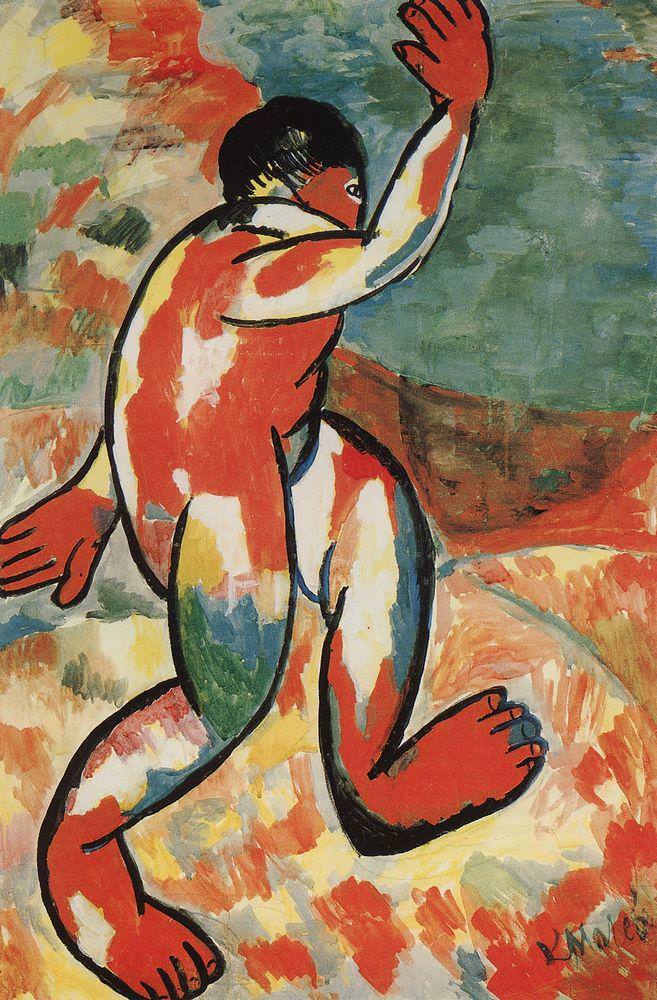

Malevich’s Fauve paintings of 1910–1911 remain startling. Bather, perhaps a direct response to Matisse’s La Danse, can be taken as an image of Malevich himself. A naked figure, with large red hands and two right feet, also large and red, is about to fling himself into unknown waters; the only visible facial feature is an eye. A picture of a chiropodist is no less exciting—and somehow no less Fauve—despite being painted in grey and the very palest of greens and yellows. Even a black and white lithograph, The Floor Polishers, carries a similar charge. The energy of Malevich’s work evidently stems not only from color but also from his remarkable ability to evoke a sense of movement. This dynamism can be sensed in work from all his different periods, whether figurative or abstract.

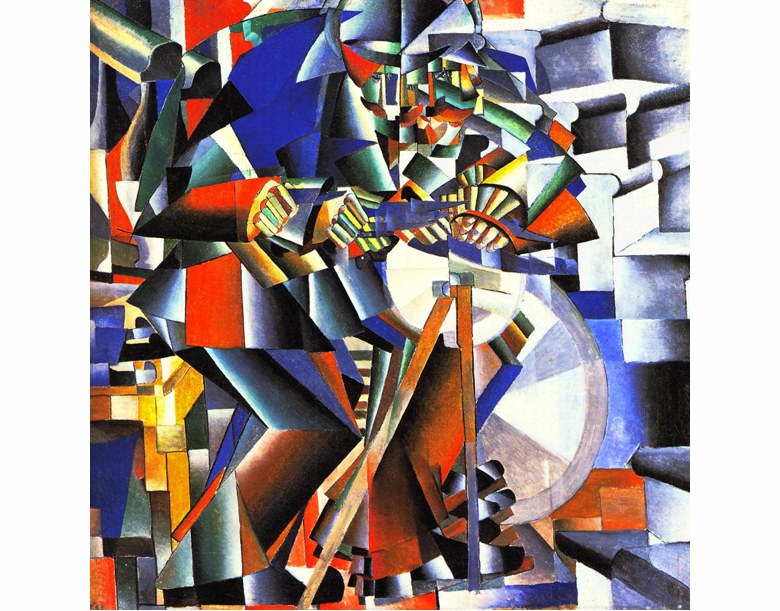

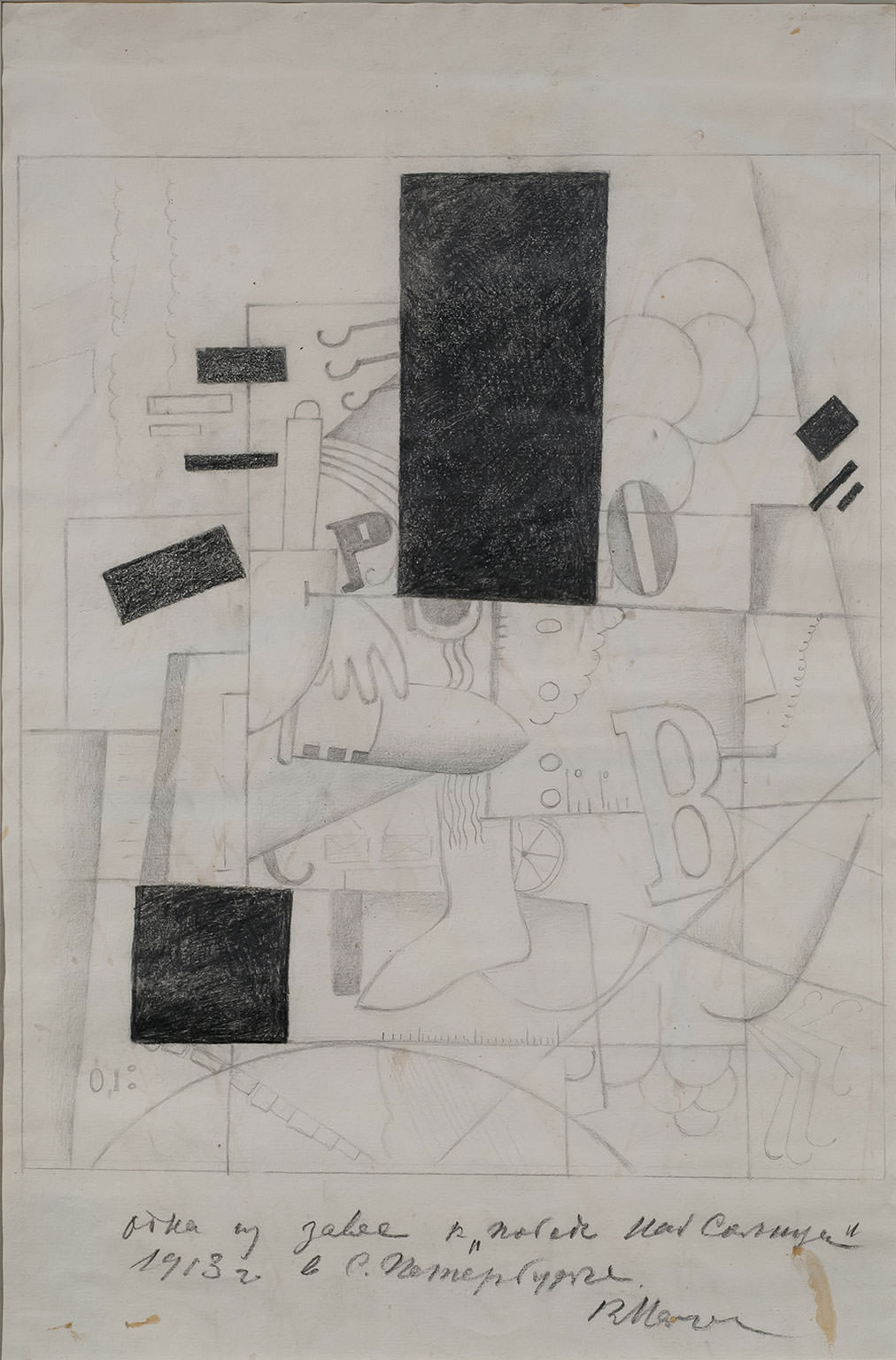

In his next period, Malevich fused the geometry of Cubism with the energy of Italian Futurism. There are paintings of woodcutters, and of peasant women carrying buckets or gathering sheaves of corn. Once again, as in icons, the eyes are the dominant facial feature. One of the finest is Knife-Grinder (Principle of Glittering). The Futurist technique of multiplying an image to convey movement has seldom been used to better effect. The left foot, operating the pedal that turns the wheel, is in at least five different positions. The fingers are too many to count. This, unfortunately, is one of the works shown at the Stedelijk Museum but not at the Tate Modern; the Tate does, however, offer a related drawing. Even in pencil, it radiates glittering, juddering life.

Malevich’s drawings have never been shown to better effect. A single large room in the Tate contains over a hundred, in chronological order, constituting a summary of all his different styles. The wittiest and most lively are from his Alogist period. Just as the Suprematist paintings anticipate most developments in abstract painting throughout the rest of the twentieth century, so these startling medleys of words and images anticipate much of subsequent conceptual art.

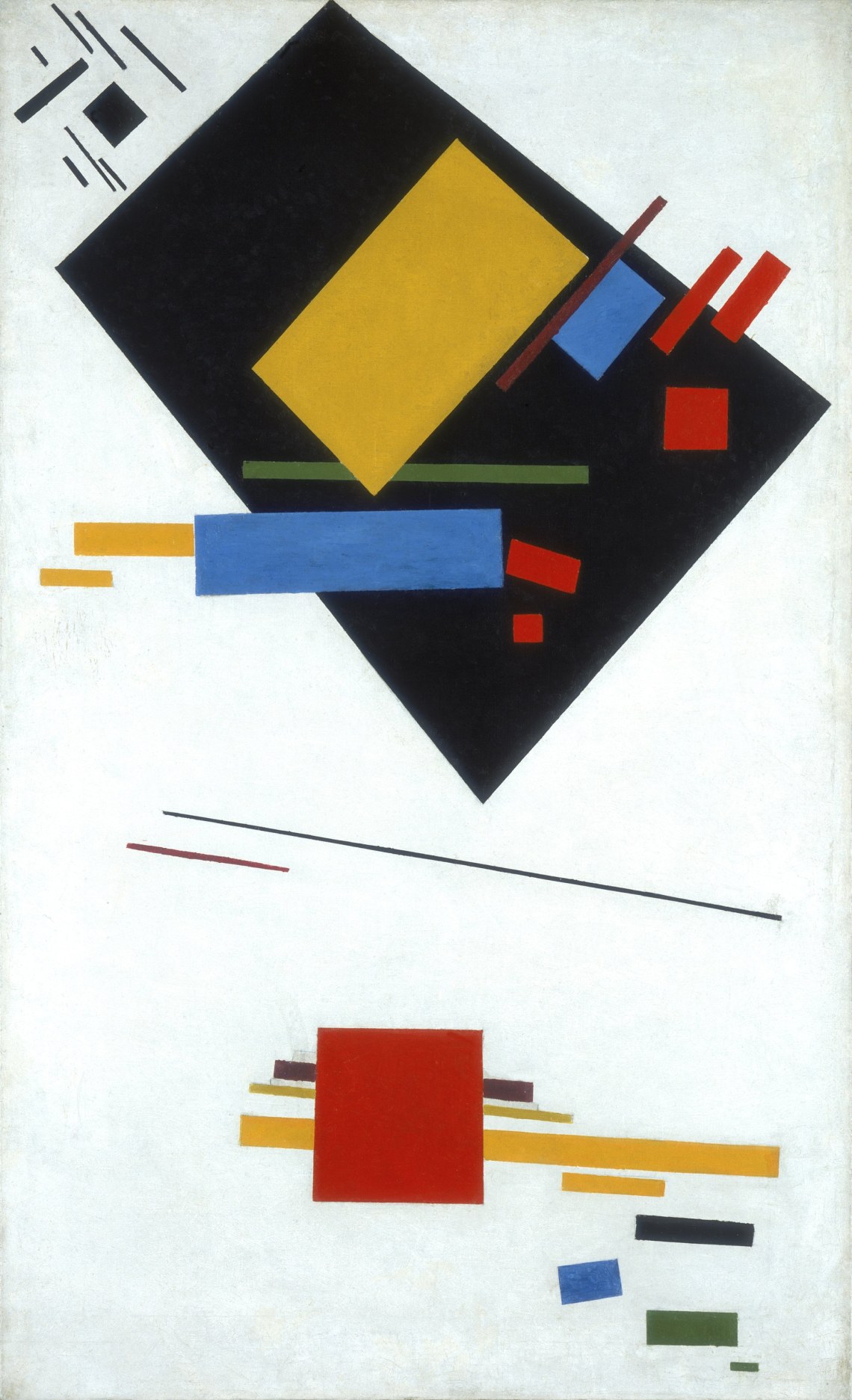

In his Alogist work Malevich intended to reveal the illusoriness of outward appearance; in the Suprematist work immediately following it, he aspired to embody what he saw as some ultimate truth. The Suprematist paintings (1915–1922) fit neatly into a generally accepted story that sees decades of artistic experimentation as a rehearsal for a final supreme breakthrough: into total abstraction. The reverence now bestowed on them, however, is excessive. They are remarkable in many ways—in their purity, their boldness, in their extraordinary variety—but there is more depth of feeling in the later work, and no less inventiveness.

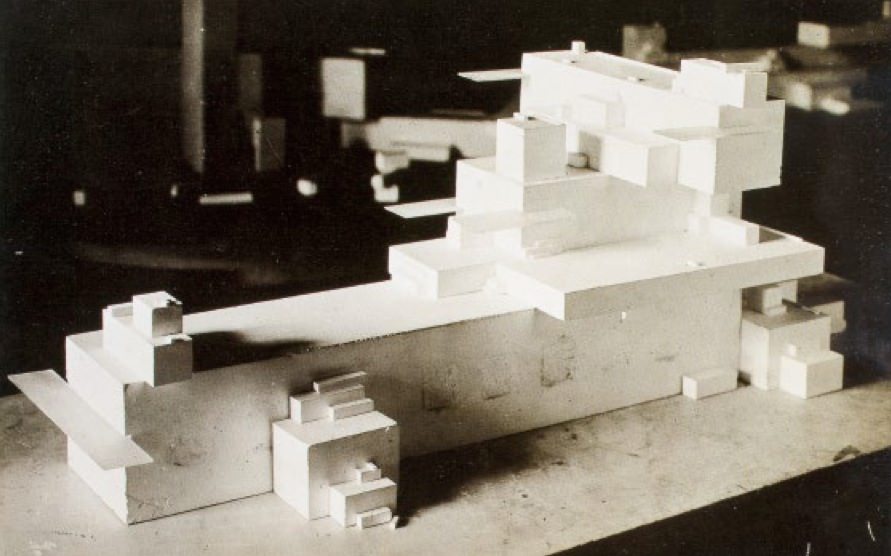

In 1919, as Malevich entered his white-on-white period, freeing himself even from color, he wrote, “I have conquered the lining of the colored sky, I have plucked the colors, put them into the bag that was formed, and tied it with a knot. Sail on! The white, free depths, eternity, is before you.” Exhilarating though this may be, it marks a temporary victory for Malevich the poet-metaphysician over Malevich the artist. Indeed, for several years in the early 1920s he abandoned painting altogether, concentrating instead on theory, astronomy, his teaching, and his work on the small models he called “architectons” or “planits,” his exploratory vision of a future Suprematist style of architecture.

Advertisement

Like other members of the Russian avant-garde, Malevich met with ever-growing hostility from the Soviet authorities. The State Institute of Artistic Culture, of which he was director, was closed down in 1926 after being publicly labeled “a government-supported monastery.” And in late 1930 Malevich spent two months in prison, accused of being a German spy. Had he not died of cancer in 1935, it is likely that he would soon have been re-arrested.

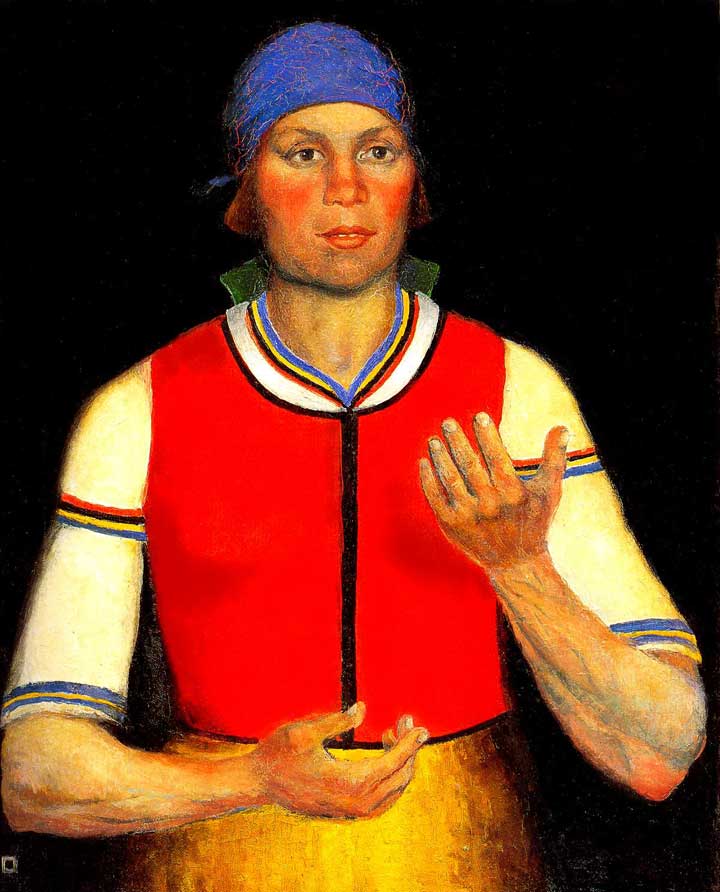

Malevich’s return to figurative work in the late 1920s is still sometimes understood as some kind of compromise or betrayal. This is mistaken—Malevich was never a man for compromise. This is clear even from his way of signing these last paintings—in a gesture of loyalty to his earlier vision he uses not his name but simply a black square. And not one of these paintings accords with the tenets of Socialist Realism; even the paintings of workers are imbued with a tenderness not to be seen in the work of more officially approved painters. As for the stark drawings of the “Second Peasant Cycle,” with their black or red crosses, their crucified figures, and their dead children, these are a profound response—like Andrey Platonov’s novel The Foundation Pit—to the horrors of Stalin’s collectivization of agriculture. There are also luminous semi-abstract portraits, such as Female Torso (1928-29), that perhaps evoke some world of future harmony. There is a dignified portrait of Nikolay Punin, the Futurist art critic and common-law husband of Anna Akhmatova, in priest-like clothes whose colors and geometric forms are reminiscent of Suprematism. There is a memorable self-portrait, in a defiant pose that evokes a famous self-portrait by Albrecht Durer. And there are portraits of the artist’s wife, mother, father, and daughter.

As Malevich’s earlier work is remarkable for its energy, so these late realistic portraits are remarkable for their humanity. The delicate grey eyes of the artist’s wife see clearly and are clearly seen. Unlike the staring, visionary eyes characteristic of the earlier work, these eyes are alert to the world of our everyday lives. They are fully realized embodiments, at a time of state terror, of clear-eyed love.

“Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art” is on view at Tate Modern through October 26.