If animals are not only bons à manger but also bons à penser (good to eat, good to think with), according to the celebrated dictum of Claude Lévi-Strauss, then monsters, while perhaps less inviting to the palate, make even better food for thought. Themselves the direct and fanciful products of attempts to understand phenomena, they appear in a wonderful variety of forms on the maps drawn up by medieval and Renaissance cartographers, as Joseph Nigg and Chet van Duzer show in two resplendently illustrated and thoughtful recent studies. Scylla and Charybdis, sea serpents and pristers offer a range of explanations for natural phenomena, such as whirlpools and reefs; indeed the abundant stories that Homer and Ovid tell draw up a wonderful narrative geography as much as a mythical history.

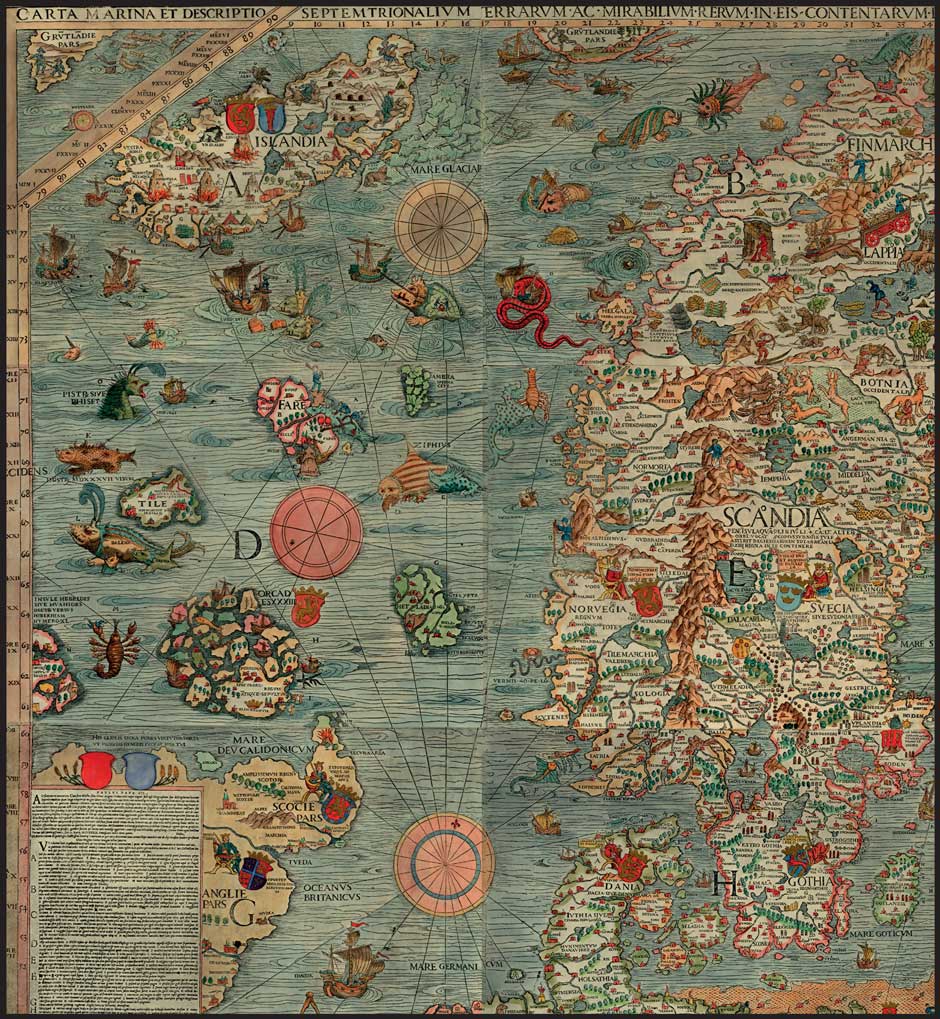

Yet in many ways maps and monsters would appear antithetical: maps are about measurement and evidence; they attempt to document a real world out there in an objective way with empirical tools tested over time; by contrast, monsters are fantasies, mostly sparked by terrors, but sometimes born of desiring curiosity, too. Both these books show how inextricably empirical observations were all mixed up with fantasies, some rooted in ancient myth and some concocted more locally, with the result that a map such as Olaus Magnus’s sixteenth-century “Carta Marina” (see Figure 1 below) presents the viewer today with a contradictory dream of reason, a high achievement of learning packed with both wonders and witness, offering a huge range of explanations and lessons in experience as well as rich entertainment and delight.

Olaus Magnus was the last Catholic Archbishop of Uppsala, and created his map of Scandinavian waters while living in exile in Danzig; he may have acted out of nostalgia for his lost homeland and pride in all its splendors, for he includes a rich inventory of sea creatures in the stormy and dangerous channels between Iceland, Scandinavia, and Scotland. Observation and fantasy coalesce: a whale is depicted suckling her young in the sea, for example, (Figure 2) and precious ambergris (spermaceti) lies floating on the surface. But other monsters convey the dangers of marine voyaging in fantastic terms. The unknowability of the ocean takes the form of “very long Worms” and huge, throttling, or poisonous hybrids, which threaten puny humans with death by devouring, shipwreck, and drowning.

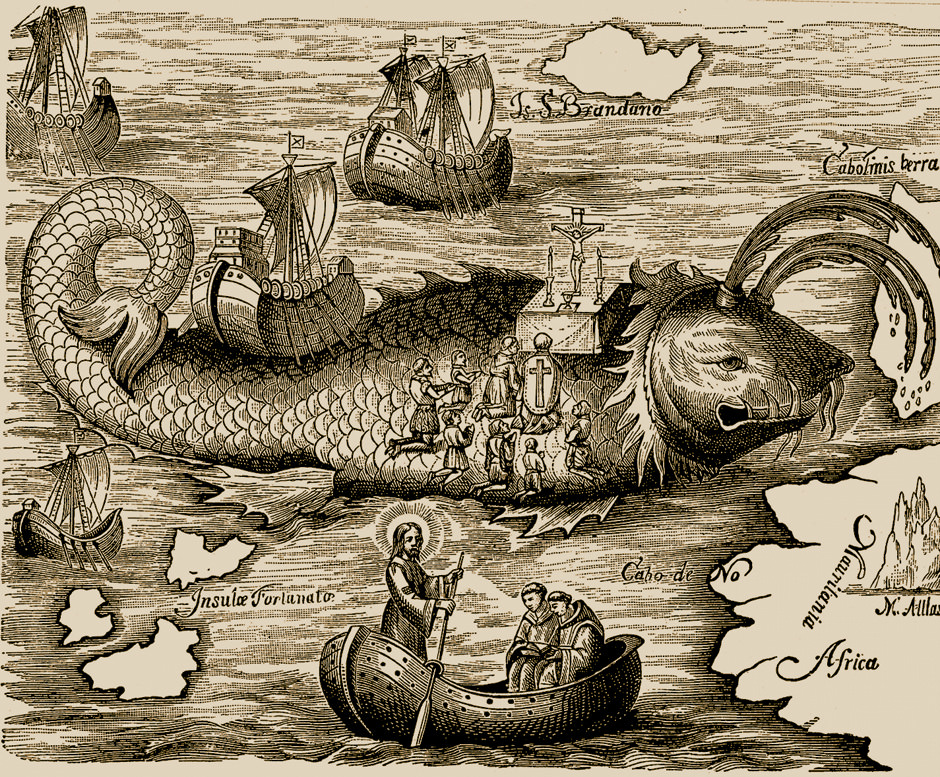

Sailors beware: do not mistake a whale for an island, and drop anchor on the creature as if in a safe haven; do not think of setting up a cooking pot or building a barbecue, for the creature, feeling the grapnels in its flesh and the flames of your fire, will sound, taking you and your picnic with you to the depths (Figure 3). The fable is ancient: it appears in Pliny’s Natural History, where the island-whale is given a name of its own, to be added to the zoological catalogue: an aspidoceleon, literally, a shield turtle. Christian commentators, as in the Harley Ms. 4751 (Figure 4) allegorized the danger, and warned unbelievers who trust in the illusions of pleasure and safety conjured by the devil, that they will be taken down into hell. On the other hand, if you set up an altar on the whale’s back, as St Brendan does on his sea voyage, and kneel down on his barnacled hide to say your prayers, the creature will bear you patiently and hold steady, even while spouting (Figure 5).

Many medieval and renaissance artists seized the chance for playful wit that the fantastic bestiary offered them, and combined and recombined the arsenal of fins, fangs, snouts, teeth, bristles, and tails; the consequences often prefigure the comic doodles of Edward Lear’s imaginary animals, like “The Dong with the Luminous Nose,” Lewis Carroll’s cartoons for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (later redrawn by John Tenniel for the books’ celebrated pictures), or even Maurice Sendak’s goofy and galumphing Wild Things, who “roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.” It is hard to believe that the audiences of the time did not smile, too, at the “marine pig-dog,” more soft toy than terror of the deeps (Figure 6).

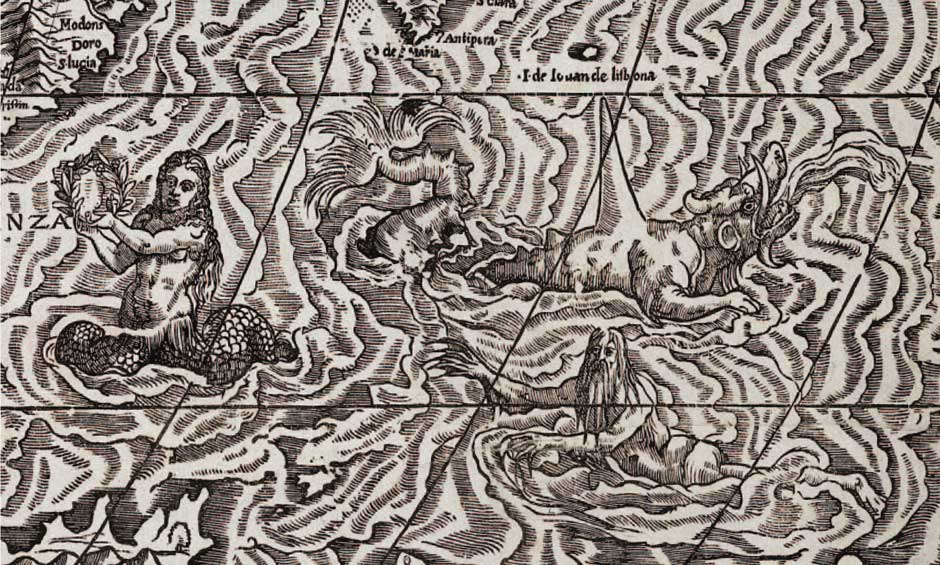

Mermaids populate the sea in myths from Scandinavia to Africa; beautiful, long-haired, and musical, they come in various species, single- or double-tailed, and sometimes in the form of sea-horses, or hippocampi. Long confused with sirens, who in Homer have bird-bodies, they lure sailors to live with them in the depths. The attraction is usually fatal: in the Odyssey, the sirens tempt wayfarers with foreknowledge of all that is to come, but the shore where they roost is littered with the bones of their victims. In the Arabian Nights, on the other hand, marrying a mermaid can be a success (in “The tale of Julnar the Sea-Born,” for example).

Advertisement

In ths map of the southern cape of Africa from Gastaldi’s Cosmographia Universalis (Figure 7), a mermaid is holding up a laurel wreath—a promise of glory. Beside her, in the roiling waves, a grotesque orcha, a sea-orc, is breathing out fire: a kind of sea dragon, his gigantic size embodies the vastness and violence of the ocean itself. Beneath him, an Old Man of the Sea, with icicle beard and webbed hands, strikes a note of pathos, as if he were condemned unwillingly to live in the sea. A similar figure makes another haunting appearance in Urbano Monte’s manuscript atlas, 1590. The Old Man of the Sea has inspired many stories which convey the shifting, mysterious and ceaselessly changing character of the sea itself: in Greek myth, Proteus can change his shape at will (hence, “protean”); Peleus takes the form of different animals in his prolonged and terrible rape of the sea-goddess Thetis—Achilles is the result; in the Arabian Nights, Sinbad offers to carry a feeble old man he encounters and then finds himself pinned down by his huge weight and goaded to carry him further and further. Most unexpectedly, Glaucus, who longed to live in the depths and ate grass that turned him sea-green, was wrought by Dante into a figure of the poet’s own redemptive metamorphosis, in the first Canto of Paradiso.

Monsters are made to warn, to threaten, and to instruct, but they are by no means always monstrous in the negative sense of the term; they have always had a seductive side. With the weakening of belief in their supernatural origins, their appeal—their animal magnetism—shows every sign of growing stronger.

Marina Warner’s piece “Here Be Monsters” appeared in the December 19, 2013 issue of the New York Review.