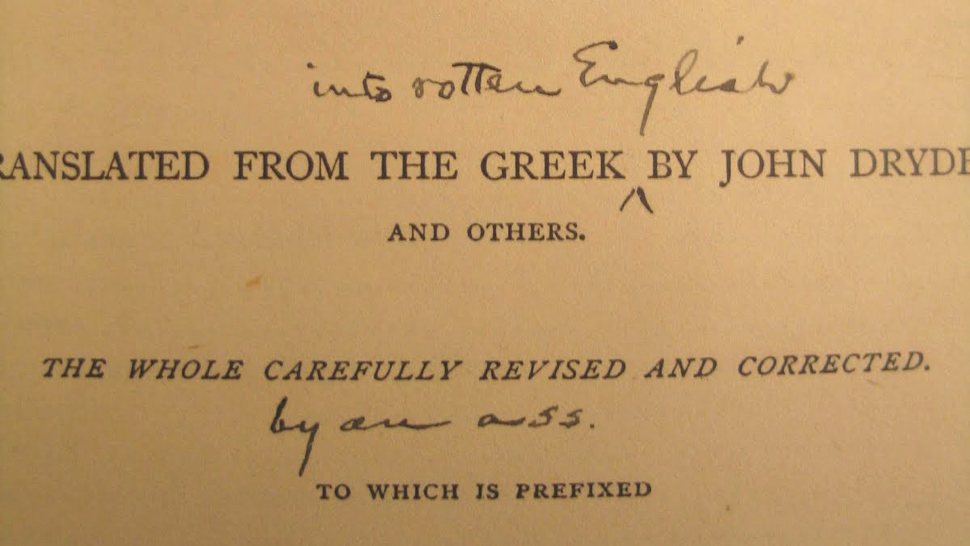

Marginalia are on the march. The New Yorker reported this fall on Oxford’s Marginalia Group, which “now has two thousand five hundred and three members, making marginalia to Oxford something like what a cappella is to Princeton.” They specialize in finding the snarkiest of the notes that generations of Oxford students have entered in their assigned books. The creator of the Oxford group, April Pierce, noted that the great libraries of London also house books full of readers’ written reactions. The London Library’s copy of Edmund Husserl’s Logical Investigations, for example, contains such striking remarks—some clearly motivated by the text, some apparently not—as “What the devil does this mean?” and “above all there should be cake.” They were entered by T.S. Eliot, who bought the book at Marburg in 1914.

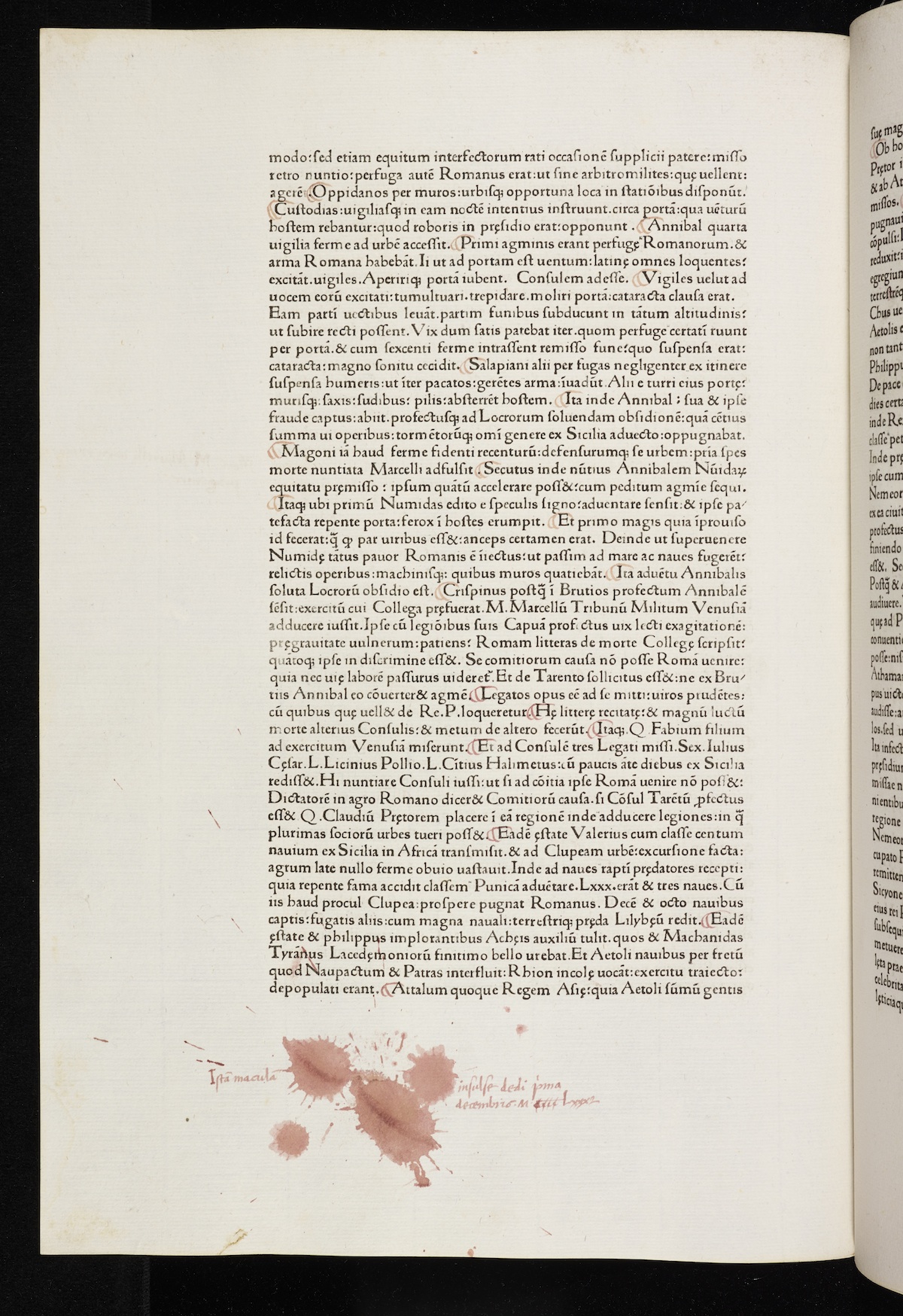

Oxford isn’t alone. A splendid exhibition currently at the Cambridge University Library recreates “Private Lives of Print: The Use and Abuse of Books 1450–1550.” The histories, romances, and devotional books showcased there have one thing in common: they were illuminated, corrected, scribbled on, and, in one wonderful case singled out by Mary Beard, covered with red ink by past owners and readers. The last spiller of ink at least apologized: “I stupidly made this blot on the first of December 1482.”

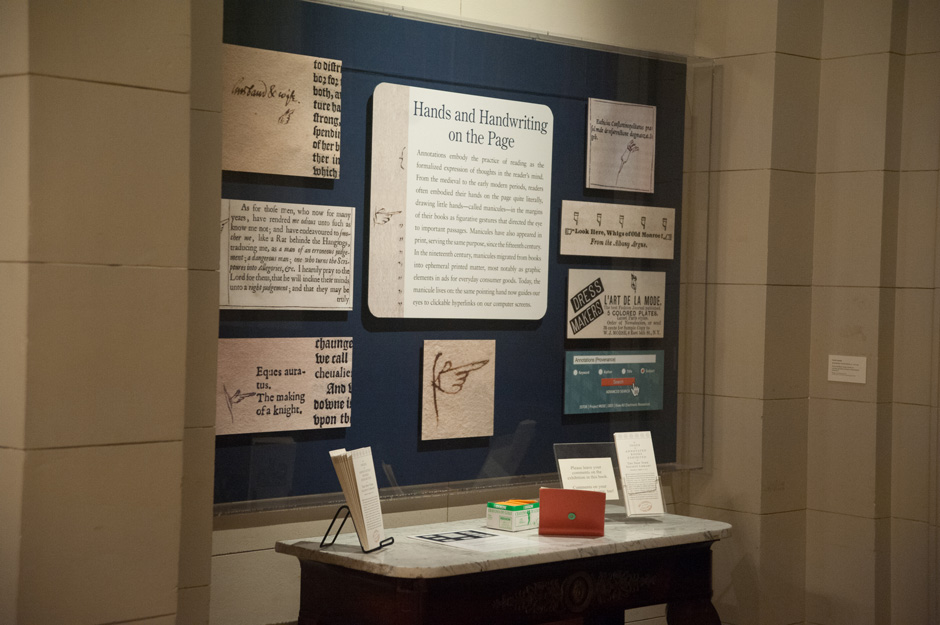

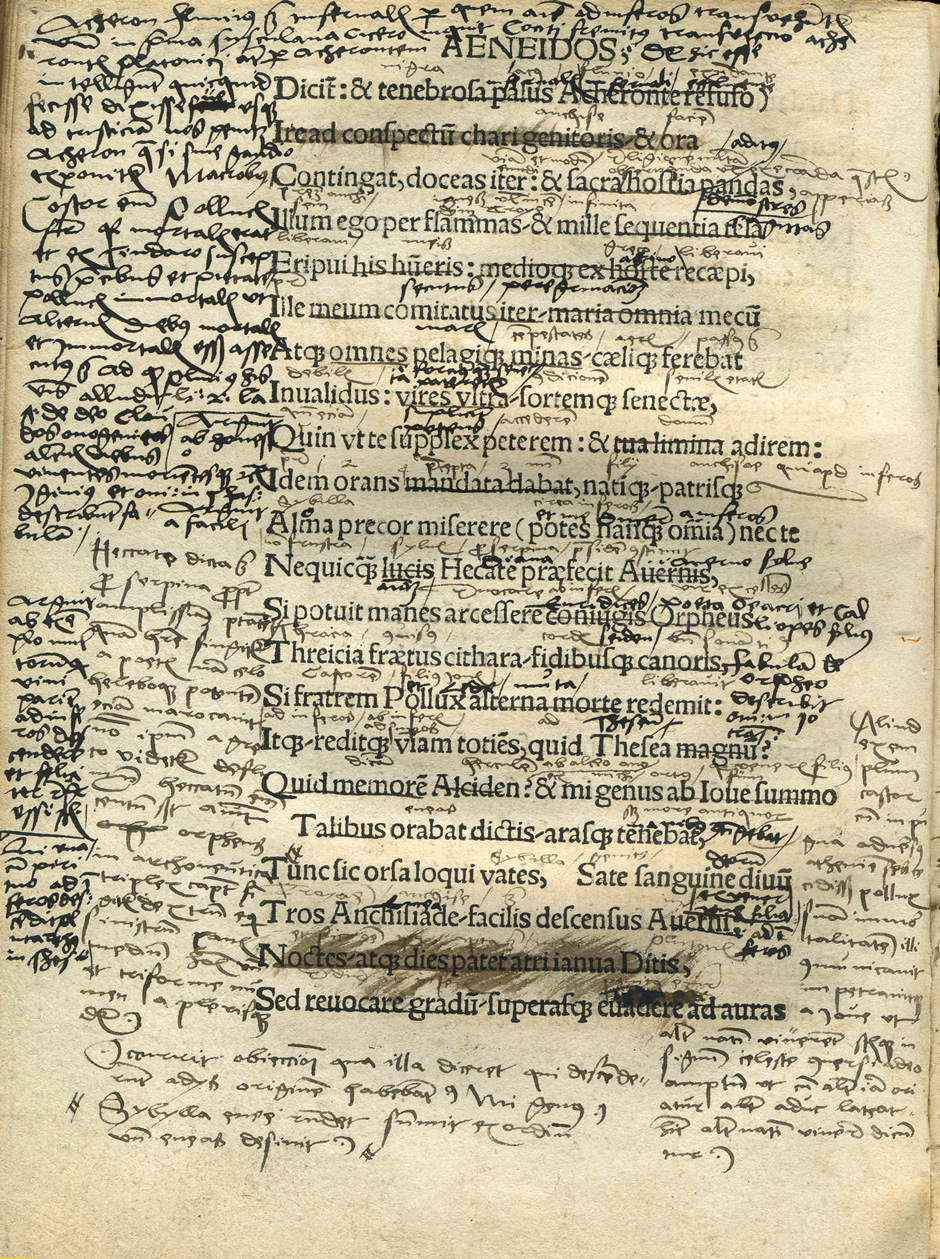

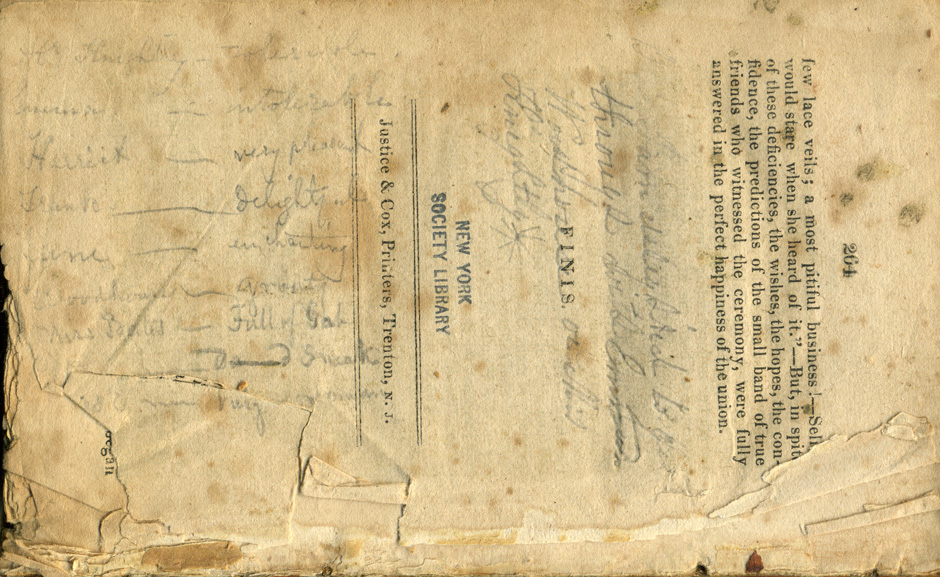

Happily, New Yorkers don’t have to confine themselves to dreaming of scrawled insults and epiphanies on other shores—or following Marginalia Monday on Twitter. On February 4, the New York Society Library, a subscription library on East 79th Street, opened Readers Make Their Mark, an exhibition of annotated books from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries from its own collection, which will remain in the Peluso Family Exhibition Gallery until August 15. In it you can see readers writing in books of every kind, for every imaginable reason. Sometimes they are learning the basics: a schoolboy in Renaissance Germany uses his copy of Virgil, printed with blank spaces between the lines and wide margins, to enter his teacher’s paraphrase of and comments on the text. Sometimes they are making proclamations about their own books: George Bernard Shaw identifies a printed text of his Too True to be Good as a “Provisional Prompt Copy” for a particular production and calls it “Frightfully Private. No Press Agent to be let near it.” And sometimes—as in the case of an early woman reader who judges the characters in Emma, one by one—they respond to their books in ways that still seem familiar (even if we would record reactions like this on Goodreads, for the world to see, rather than in the pages of a single copy).

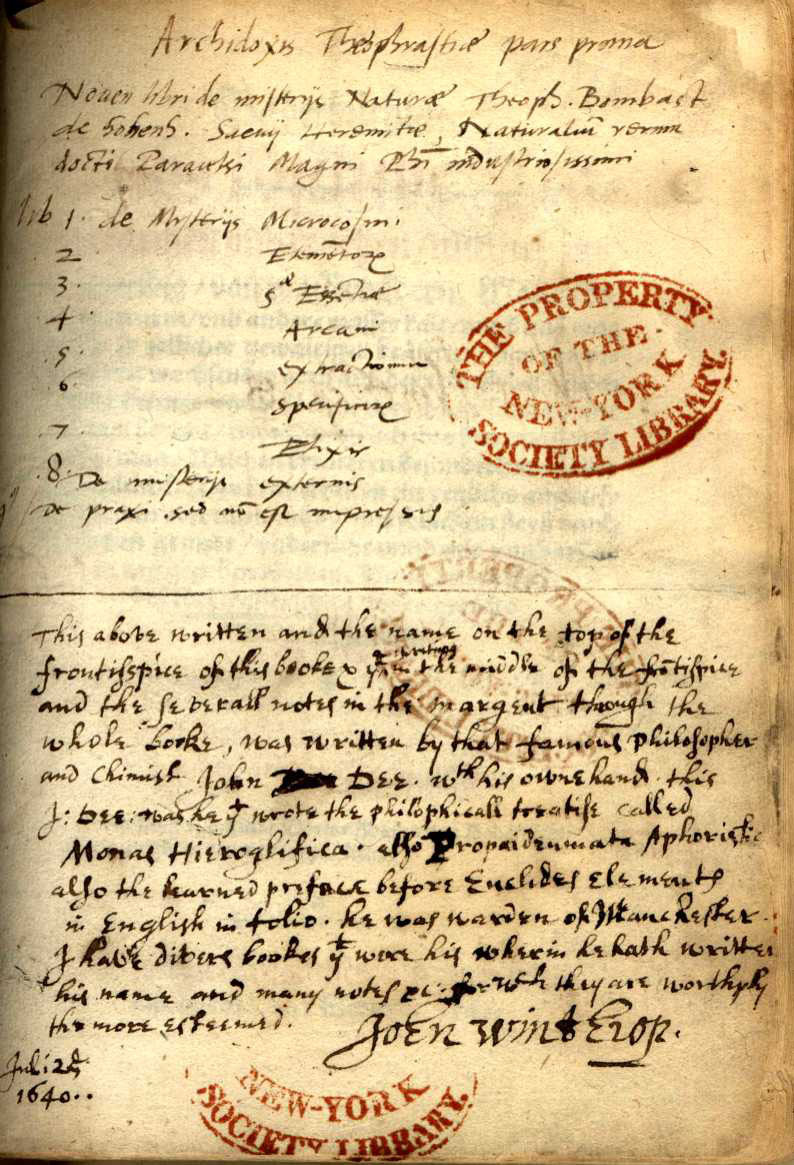

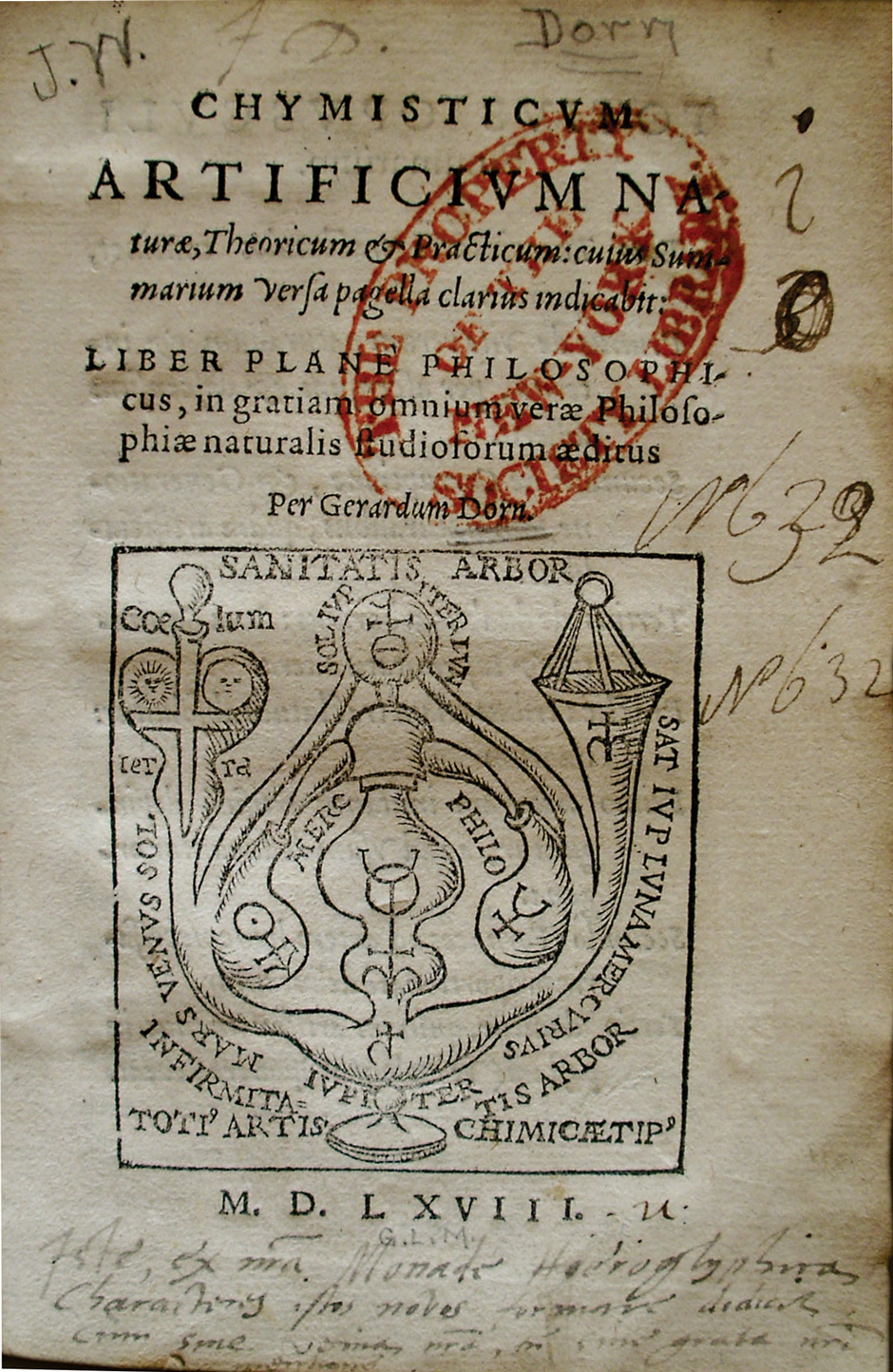

Often they summarize, at length: when John Dee, cartographer, alchemist, and astrologer, reads a book on medicinal baths, he copies its content almost line by line in his dazzlingly pretty Renaissance script (my teacher used to say that a great man with great handwriting is twice a great man). Many add the pre-modern equivalent of Post-its—the manicules, or pointing hands, that called attention to important passages and recalled the up-close and physical nature of reading when it was properly carried out, pen in hand. Others—like the members of the Winthrop family, who started annotating in England in the sixteenth century and were still scribbling in their books in Massachusetts and Connecticut, generations later—make the blank pages in their books into notebooks, which they fill with information about the author in question and any similar books they know.

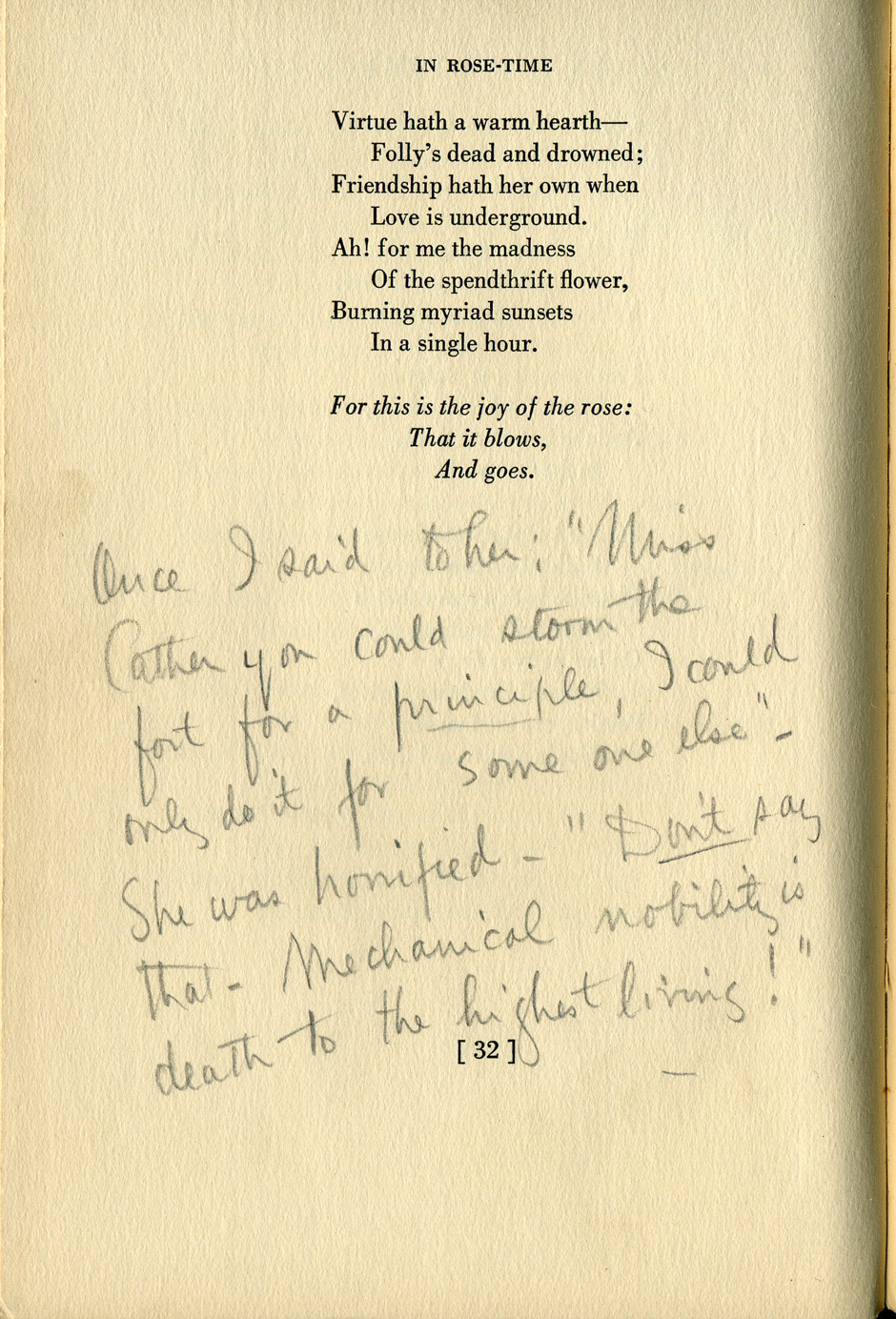

Annotation has never ceased to be practiced. But it does change forms and practitioners. In nineteenth- and twentieth-century America, as Andrew Stauffer has shown with his crowd-sourced Book Traces project, which has trawled the stacks of big American libraries and fished up fascinating, forgotten marginalia from circulating collections, women often entered both rich responses and detailed accounts of their own lives into volumes of poetry—especially poetry by other women. The Society Library’s copy of Willa Cather’s April Twilight and Other Poems belonged to her friend Mary Cadwalader Jones, who filled its blank spaces with memories of conversation with Cather. “Once I said to her,” a characteristic note begins, “‘Miss Cather you could storm the fort for a principle. I could only do it for someone else.’ She was horrified. ‘Don’t say that. Mechanical nobility is death to the highest living.’” In this and many other cases, only the margins preserve the voices of the dead—the mighty and the forgotten alike. A collection like this one extends our literary archive in important ways.

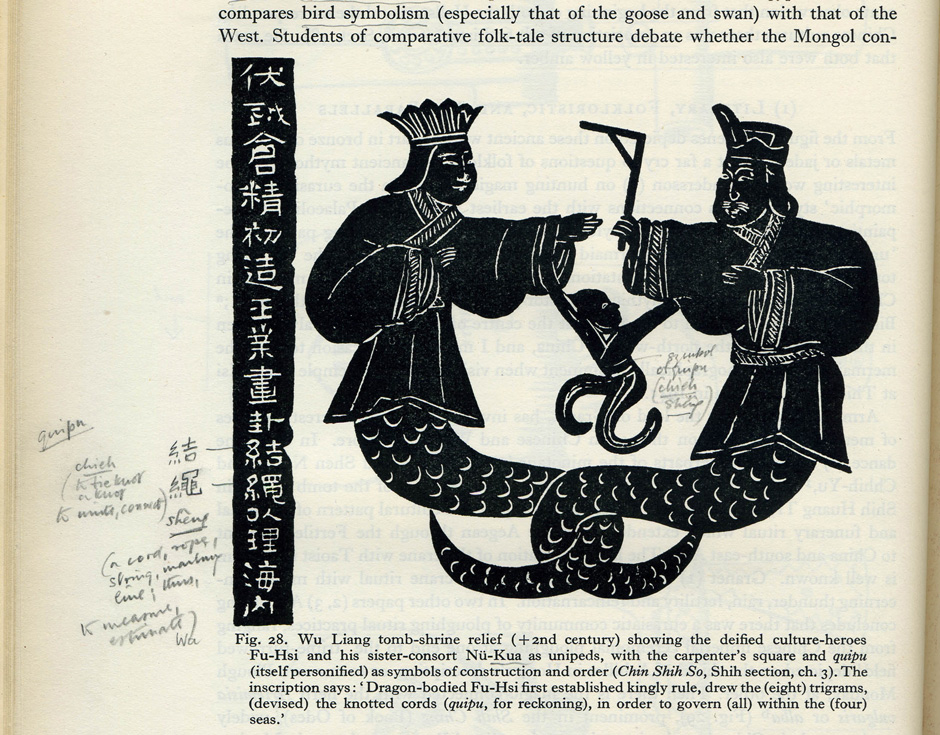

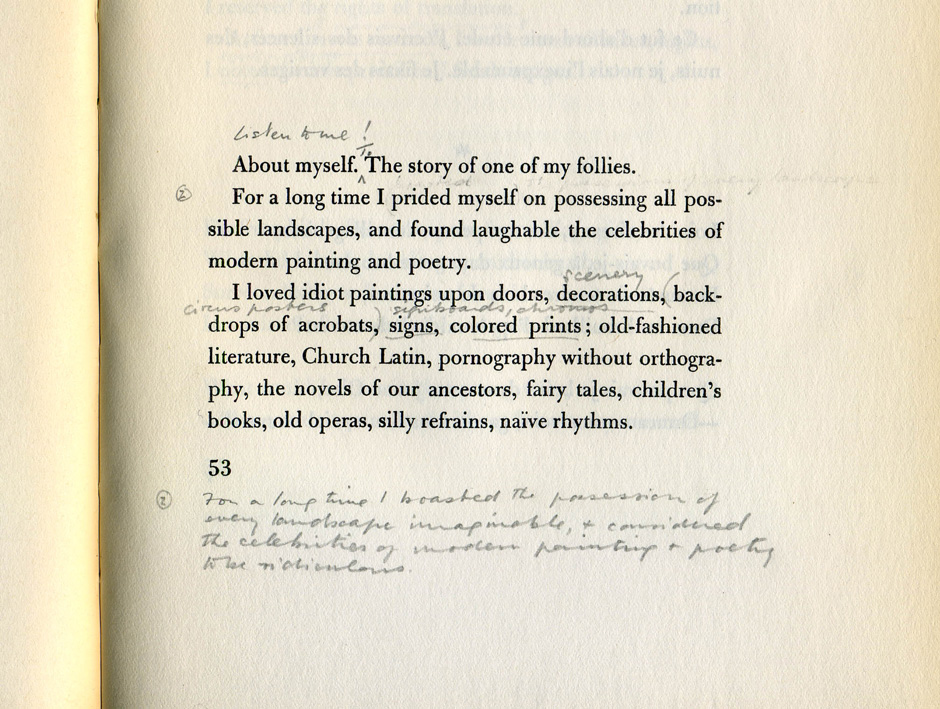

No form of annotation belongs exclusively to one period or one gender. Painstaking, legible summaries of esoteric information, ordered paragraph by paragraph, seem the perfect occupation for ancient male polymaths like John Dee. But one of the richest veins of marginalia in the Society Library’s collection was laid down by Mai-mai Sze—a very moderm Wellesley-educated artist who lived in Manhattan in the Thirties and after, working as a designer and lecturing on China. Her formidably slinky portrait—photographs of her appeared in Vogue—lights up one wall panel. And her still more impressive penciled notes record the unremitting work with which she mastered classical Chinese texts and made herself the Bollingen Series’s expert on East Asian aesthetics. It’s a special delight to watch her rough up Delmore Schwartz’s notoriously wild translation of Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell.

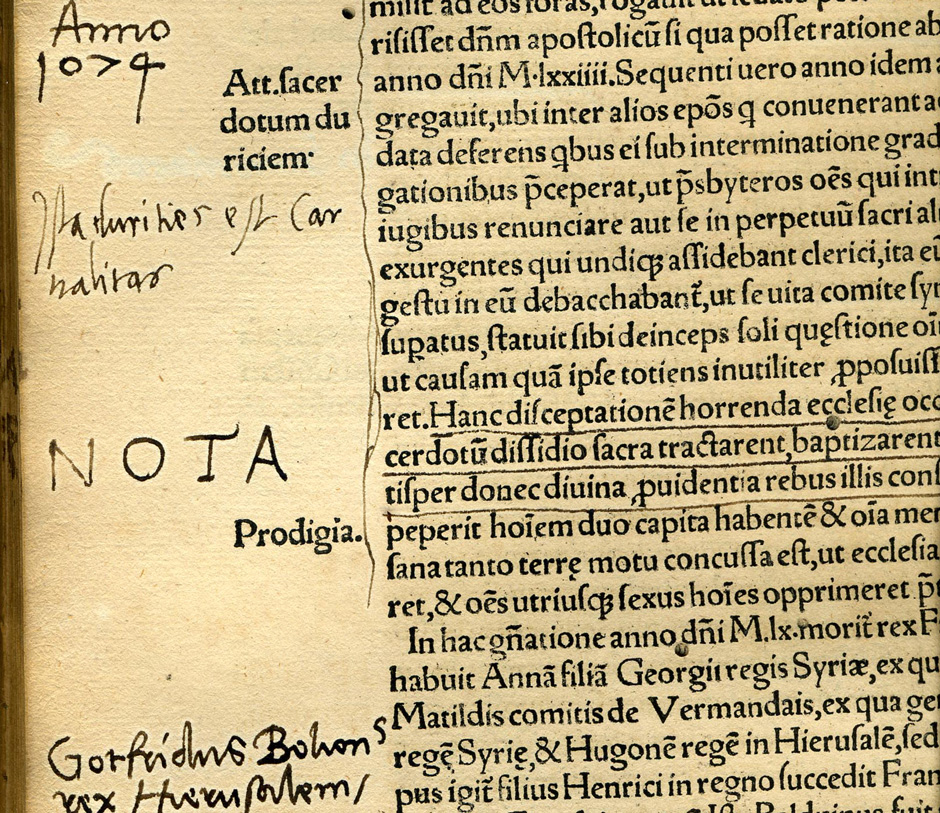

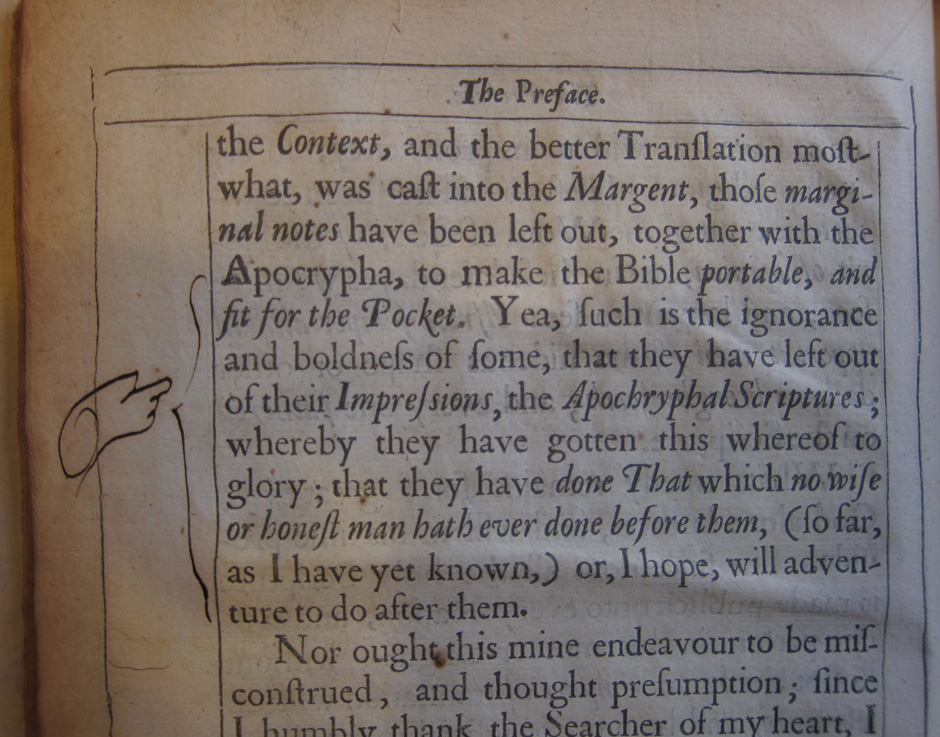

The Society Library forbids contemporary users to write in its books. A printed slip inside one of the texts on display in the exhibit shows that it has been saying no to readers armed with pens for a long time. But annotated books have had a central place in the Library’s collections from the very start. John Sharp, a Scottish-born minister with a passion for social justice, worked up a project in the 1710s to create a free school and library in New York. He built a substantial collection, in the hope that ministers who preached to African slaves and Native Americans could use the books. Some 149 of Sharp’s books eventually entered the Society Library at its founding in 1754. And he seems to have liked marginalia, since he bought a fair number of annotated books and entered notes of his own in others. In one of the books on display in the exhibition we see him take note of the author’s complaint that printers have omitted “marginal notes, together with the Apocrypha, to make the Bible portable, and fit for the Pocket.” Sharp called attention to the passage, naturally, in the margin, with a neat manicule and a bracket. The tradition has continued over the centuries, from the Winthrop collection and other individual items—such as a superb Renaissance world history, heavily annotated by the Augsburg scholar Konrad Peutinger early in the sixteenth century—to the books that document the sad story of John Romeyn Brodhead, the would-be historian of New Amsterdam, a Democrat who lost the chance to publish the documents he had collected in Europe when the Whigs took over the New York legislature and assigned the task to others, on down to Austen, Cather, and Shaw.

The three curators—Frederic Clark, Madeline McMahon and Erin Schreiner, the library’s special collections librarian—use their limited space with learning and ingenuity. (Full disclosure: Clark and McMahon both studied with me: but they and Schreiner conceived and created the exhibition with no guidance from me). Curiosities and ironies abound. A charming wall panel reproduces a whole series of manicules—from specimens drawn in sixteenth-century margins, to printed pointing hands from nineteenth-century media, to the digital pointing hand that still guides us when we search for an article in JSTOR. Others tell the tales of Mai-mai Sze and the Winthrops. The reader in search of still more information can find it in a different sort of marginal comment: lively blog posts by all three of the curators. Meanwhile the books themselves, handsomely displayed and clearly explained, speak eloquently of the people who have read and responded to them, many of whom would otherwise be unknown. Marginalia, it seems, are catching. Where will they strike next?

Advertisement

Readers Make Their Mark is on view at the New York Society Library through August 15.