On October 2, I joined hundreds of thousands of other Irish voters in approving the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty by a surprising majority 63 to 33 percent.

Because of the nature of its constitution, Ireland is the only country in the EU that had to hold a referendum on the treaty, which attempts to streamline, simplify, and, to some extent, further centralize the management of the European Union. Barring a decision to the contrary by a Czech court, or a refusal to sign by the Czech president, it will come into force before the end of the year. But the distance between the European electorate and their leaders on questions of further European integration and the softening of national sovereignty will not go away.

Only two years ago, in 2007, the same treaty was defeated 53 to 47 percent in a referendum in Ireland. In 2005, the European Constitution (an earlier version of the document that became the Lisbon Treaty) was struck down in France and Holland.

What these defeats had in common was that in each of the three countries all the main political parties supported a yes vote. Thus the result came as a shock to these ruling parties and also to those at the EU headquarters in Brussels who had drafted the constitution and then the treaty: the people had become the enemy, or a group who did not know what was good for them.

Those who opposed it in Ireland came from both left and right, from an old nationalism and a conservative Catholicism, from elements within the society opposed to the free movement of capital and workers within Europe. They came from those who understand the European Union as a vast and uncontrollable force for secularization. They came from those who oppose the idea of a European army, or who abhor the idea of Europe as a bloc with one voice on defense or on taxation policy, rather than merely a group of nation-states who cooperate economically—the original impulse behind the creation of the European Economic Community, which Ireland and Britain joined in 1973.

Over the past fifteen months, the people who voted no in Ireland, the recalcitrant ones, have been studied with forensic care, in the same way as a doctor might study a rare disease. All their motives and fears, all the reasons, both logical and ill-informed, for their voting no were gathered. And slowly a second campaign was built to question the motives of those who opposed the treaty, and allay their fears and offer them new guarantees and suggest new reasons why they should vote yes and follow their leaders into a bright new Europe.

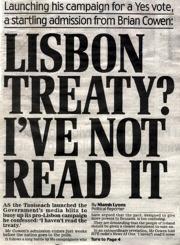

It was difficult for those of us who supported the treaty, who voted yes the first time and again on October 2, to make serious arguments about the benefits that would result from the it. The Lisbon Treaty was couched in complex legal language; many of its articles referred to other treaties and pieces of EU legislation. It was written to be interpreted by a court or a lawyer. Even most politicians who argued for it had not read it because they could not. It was, literally, unreadable. Those who drafted it did not even consider, it seems, how it might be sold to a suspicious electorate.

Thus the Irish government over the past sixteen months learned what issues had caused some of the electorate to vote no. These included the idea in the treaty that there were too many commissioners and there was no need for each country to be guaranteed a commissioner, and the fear that the treaty would force the legalization of abortion in Ireland. It included also the possibility of changing Ireland’s low tax on the profits of multinational industry, and the possibility of conscription of Irish citizens into a European army. The Irish government sought and won guarantees and assurances on these issues, some of which were not mentioned in the treaty at all, from the European partners. The yes side used these very effectively in the campaign to argue for a change of heart among no voters. In a time of rising unemployment, they also warned that a no vote would lead to further job losses. (It was notable that, in general, the less privileged the constituency, the more likely it was to vote no.)

So the yes vote had a large majority on October 2. But it is unlikely in the future that people in Europe will get many opportunities, as we did in Ireland over the past fifteen months, to have their fears debated and discussed, and then vote—not once but twice—accordingly. The crude mechanism of a referendum on a complex issue is not likely to become the norm anywhere in Europe. Most of the referenda held in recent years in member states have shown that there is a gap between the people and their rulers over the progress of the European Union. While this gap will not actually have grave consequences in the foreseeable future, in any analysis of how power is held and wielded in Europe now, it has to be taken into account.

Advertisement