After a stormy eight-year reign, New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein announced last week that he was stepping down to work for Rupert Murdoch. Mayor Bloomberg immediately selected another non-educator, Cathleen Black, the chairman of Hearst Magazines, to take charge of the school system.

What is most striking about the mayor’s decision is that he seems to see the superintendency as a job not for an educator, but for a manager. Klein’s time in office was marked by frequent dramatic reorganizations of the school system, first centralizing all authority and imposing a single reading and mathematics curriculum, then decentralizing the curriculum, eliminating most school supervisors, and giving principals extensive autonomy. To understand the significance of the major changes the mayor has made, it’s worth looking at how the education system’s highest leader has been selected in the past.

Ever since New York and Brooklyn were united with various outlying villages and neighborhoods into a single metropolis in 1898, the New York City Board of Education has overseen the city’s public schools. For most of that time, the city’s appointed Board of Education selected the leader of the school system, and that person was the leading educator in the city, someone who held the respect of his peers throughout the school system.

Over the years, the number and composition of the Board of Education varied, but for most of the twentieth century, the mayor appointed its members to a term of office, during which they served independently of him. This distance between the board and the mayor was intended to shield the schools from partisan politics. The appointees were usually outstanding citizens whose qualifications were, at different points in the past century, reviewed by an independent screening panel. Their most important responsibility was selecting the school system’s leader.

For the first half of the twentieth century, the system had enormous problems, many of them owing to severe overcrowding, but also to the special demand in New York City schools for programs and facilities for children who didn’t speak English and whose families lived in desperate poverty. The first superintendent of the city’s consolidated school system was William Henry Maxwell, who served for two decades, from 1898 to 1918. During the 1920s, when the school system was overseen by two superintendents, William L. Ettinger (1918–24) and William J. O’Shea (1924–34), the city experienced a school building boom that provided an unprecedented half a million new classroom seats. There followed several other experienced leaders, Harold Campbell (1934–42), John E. Wade (1942–47) and William Jansen (1947–58).

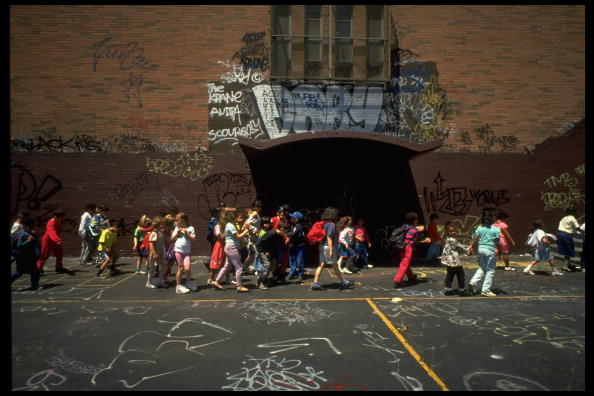

Then began a half century of instability, marked by battles over desegregation, community control, and decentralization, as well as occasional scandals and corruption. In the second half of the twentieth century, the school system saw eighteen superintendents come and go in times of upheaval, protest movements, strikes, and student riots.

Yet, despite the changes at the top, the system itself was remarkably stable. For example, it had undergone dramatic demographic change, from a white majority to a non-white one (the tipping point was 1966); still, when federal tests were given to several urban districts in 2002 and 2003, the New York City public schools performed surprisingly well—not at the very top, compared to other cities, but far from the worst.

But this was before the radical restructuring that occurred under Mayor Bloomberg. In 2002, the State Legislature awarded control of the city’s public school system to the mayor, giving him sole control over the choice of the system’s leader, now called chancellor. The board of education was no longer independent of the mayor; nor did it have any role in selecting the chancellor of the school system. Bloomberg used this power to select a non-educator, Joel I. Klein, to be his chancellor.

And what has been the result? The mayor and Chancellor Klein have frequently spoken of “historic gains” in the city’s test scores and graduation rates, but these claims were undermined when the New York State Education Department admitted last June that state officials had repeatedly lowered the passing mark for the state tests and had tested only a narrow band of its standards, thus making the tests predictable and inflating scores across the state. The recalibration of the state scores revealed that the achievement gap among children of different races in New York City was virtually unchanged between 2002 and 2010, and the proportion of city students meeting state standards dropped dramatically, almost to the same point as in 2002.

Graduation rates have risen, but so has the use of “credit recovery,” which enables students who failed a course to gain credit by taking shortcuts, either by submitting an unmonitored essay or “repeating” an entire course in just a few days. In fact, 75 percent of those who graduate from New York City public schools and enter the community colleges of the City University require remedial work in reading, writing, or mathematics. In these circumstances, one wonders about the value of the graduation rate as a measure of readiness for further education.

Advertisement

State law requires that the job of school superintendent or chancellor must go to a person with specific credentials and qualifications, including certification as a superintendent, completion of graduate education courses, and three years of teaching experience. The law provides that a waiver may be offered to individuals “whose exceptional training and experience are the substantial equivalent of such requirements.” Although Ms. Black lacks the requisite experience, it is generally expected that the mayor will obtain a waiver from the state for his new chancellor-designate. Ms. Black would be the third chancellor in a row, following Harold Levy of Citibank (who was appointed by the pre-Bloomberg board, and who had previously served on the New York State Board of Regents) and Joel Klein of Bertelsmann, to receive a waiver.

Like many New Yorkers, I am willing to give Ms. Black a chance. Although she is a trustee of Notre Dame and serves in an advisory role on the board of a charter school, she will have much to learn about her new responsibilities. One hopes for fresh thinking that goes far beyond the well-worn and not very successful formula of testing, accountability, and choice. She will soon take charge of the education of more than one million children. For their sakes, we must all wish her good luck.