Statues of the illustrious (or at least famous) dead used to be added to the American cityscape with predictable regularity, especially after wars, assassinations, and the demise of beloved (or at least respected) public figures. But by the second half of the twentieth century, the ascendancy of abstract art, coupled with the unprecedented horrors of recent combat and genocide, made representational memorials seem increasingly inadequate.

Now, twenty-four years after Andy Warhol’s death, the long-obsolete memorial statue has been given new life with The Andy Monument, a dazzling, lifelike, ten-foot-tall effigy by Rob Pruitt, lately unveiled in front of 860 Broadway, the building on New York’s Union Square that housed the subject’s studio (which, like his original space on 47th Street, he called the Factory) from 1974 to 1984.

Sponsored by the Public Art Fund, the statue is set atop a concrete pedestal inscribed with the work’s title and depicts the artist—instantly recognizable by his Slavic features, affectless bespectacled gaze, and lopsided silver fright wig—wearing his preppy uniform of navy blazer, Levi’s 501 jeans, white button-down Brooks Brothers shirt, and striped necktie, with a Polaroid camera hung around his neck. As things stand, The Andy Monument is meant to be a temporary installation, and will be taken down in the fall. One can only hope that this visually arresting and unexpectedly touching memorial will remain a permanent part of the city Warhol did so much to illuminate.

Pruitt combined digital imaging and hand modeling techniques (which would have pleased his multi-media-minded subject) and rendered his simulacrum with a chrome-plated finish reminiscent of the stainless steel Luxury and Degradation sculptures (1986) by Jeff Koons, today’s closest counterpart to Warhol. That silvery surface is also the ideal medium for a memorial to the artist who in his and Pat Hackett’s book Popism: The Warhol Sixties, spoke of the magnetic attraction he felt for that metallic tone:

[I]t was the perfect time to think silver. Silver was the future, it was spacy—the astronauts….and silver was also the past—the Silver Screen….And maybe more than anything, silver was narcissism—mirrors were backed with silver.

Several scholars, including Wayne Koestenbaum and John Richardson, have stressed the centrality of the looking glass in interpreting Warhol, whose most telling early works—above all his Death

and Disaster series—held up a pitiless mirror to the violence of contemporary American society with brutal images of race riots, car crashes, poisoning victims, suicides, most-wanted criminals, and electric chairs. Indeed, there is no better sound track to this mercurial artist’s story than Lou Reed’s 1966 song “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” recorded by The Velvet Underground and Nico, the rock group that Warhol briefly managed and which served as the Factory’s house band.

Stopping by to see Pruitt’s shiny new apparition, I was reminded of the one time I visited the Factory. In the fall of 1982, when I worked at House & Garden, the magazine’s chief editor, Louis Oliver Gropp, and I were invited to lunch with Warhol, in preparation for an article on the Factory that would be written by Richardson and shot by the legendary fashion photographer Horst P. Horst (who were yet to receive the assignment).

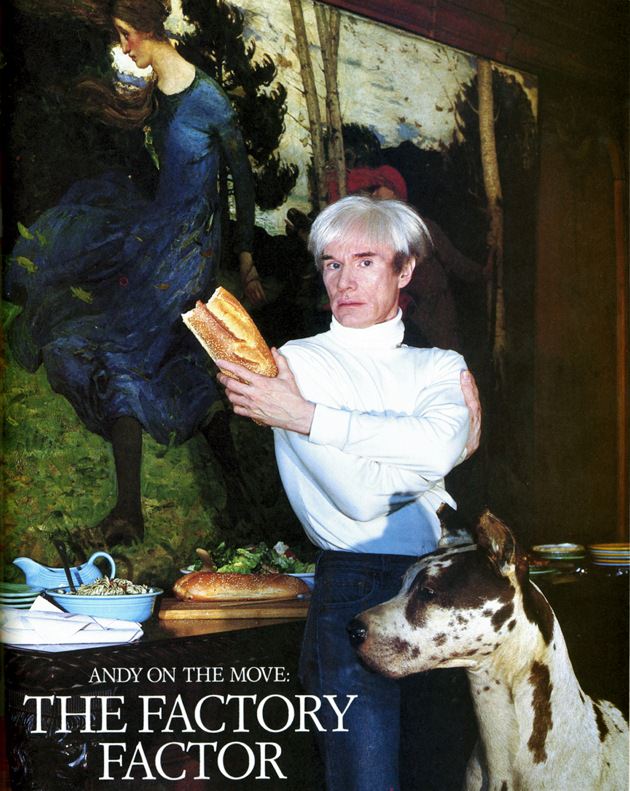

The meal was served in the Factory’s wood-paneled art-and-antiques filled Boardroom, a vestige of the space’s previous occupants, Sperry & Hutchinson, makers of Green Stamps—the verdant subject of a prime 1962 Warhol canvas given to the Museum of Modern Art by Philip Johnson.

The buffet—a variety of indifferent store-bought salads—was set out on a sprawling Irish Regency mahogany sideboard and served on mismatched multicolored Fiestaware plates. Above the food hung a frieze-like painting of windswept girls herding a goat, the work of an obscure Scottish Pre-Raphaelite. Nearby stood a taxidermy Great Dane on wheels that added to the dizzy high/low juxtapositions typical of the Reagan-era Warhol style.

Gathered around the oval Ruhlmann dining table were Warhol, Gropp, and myself, along with Warhol’s business manager, Fred Hughes; the Swedish collector Hans Thulin; the Swiss art dealer Bruno Bischofberger; the movie producer Lester Persky; and the New York housing developer Samuel LeFrak and his wife, Ethel. The LeFraks were there to be immortalized by Warhol, who charged $25,000 for single portraits, or $40,000 a pair, which the couple had chosen.

Lefrak wore what appeared to be an admiral’s full-dress uniform, complete with service ribbons and a white cap that he kept on throughout the meal. He held forth as if the guest of honor, but as attention shifted from him and conversation naturally broke down into smaller groups, he grew visibly perturbed. Several times he rose at his place to address the group at large. “Sam, whaddya doing?” Persky groused. “Siddown! This isn’t a public meeting!”

Advertisement

But LeFrak clearly captivated Warhol when the subject turned to that favorite Manhattan dinner-party topic, residential real estate prices. “We see LeFrak City on the way to the airport,” the artist told the landlord, and then asked, “How much do your apartments cost?” When he heard that two-bedroom flats in the Queens development could be rented for just a few hundred dollars per month, Warhol excitedly called across the table to Hughes, “Fred, Fred, did you hear that? Wow, that’s so amazing! Oh, we should move to LeFrak City, we really should.”

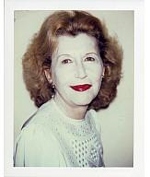

Warhol seemed almost a guest at his own party—shy, amiable, but more than a bit lost—and Hughes, far from showing deference, treated him as if he were an annoying great uncle who had to be tolerated at the family Thanksgiving feast. After we’d eaten our cold pasta primavera and downed our white wine Hughes brightly asked, “Who wants to see Andy do a portrait?” Ethel Lefrak had slipped away before the meal was over, and in the large adjoining workroom—as fluorescently utilitarian as the Boardroom was aspirationally grand—we found her seated while a hair-and-makeup team fluffed her voluminous coiffure, used a small paint roller to slather her face with thick Kabuki-like pigment (a camouflage trick that flatteringly erases all wrinkles under a photographic flash), and finished with two slashes of vermilion lipstick.

Finally the milling crowd of supernumeraries parted and Warhol—who had been on the studio phone nonstop but spoke so softly it was unclear whether these were business or social calls—was handed a Polaroid camera. He turned it toward the anxious-looking Mrs. LeFrak and pushed the button, but before the instant film expelled itself an assistant whisked the apparatus from the portraitist’s hands and completed the developing process. Amid the hubbub, Hughes turned to me and solemnly confided, “Andy is like Rubens. He needs to have lots of people around him in the studio. It helps alleviate his creative anxiety.”

Andy Warhol: Samuel and Ethel LeFrak, 1982. Warhol dictated the following entry in his diary for January 2, 1983: “The LeFraks called and said they still hated their portrait. Mr. LeFrak said why weren’t Mrs. LeFrak’s eyes hazel in the portrait, and then he said his nose was too bulbous. So maybe if we fix those two things it’ll get by.”

And now, with his shiny effigy in Union Square, Warhol is happily surrounded by admirers. (The artist’s Liz #5, a 1963 portrait of Elizabeth Taylor from the collection of hedge fund manager Steven A. Cohen, is being auctioned by Phillips de Pury in New York on May 12, is expected to fetch between $20 and $30 million.)

Apart from the statue’s silvery patina, Pruitt’s most inspired touch was to have him holding an emblem of his favorite department store—Bloomingdale’s generically emblazoned “medium brown bag” (designed in 1973 by Massimo Vignelli). It is employed in much the same way that Catholic saints are shown with the attributes of their martyrdom, like St. Catherine and her torture wheel.

Warhol carried these brown-paper totes during his daily peregrinations on Madison Avenue, where he handed out copies of Interview magazine to startled passersby and called in at the tiny antiques shop of Vito Giallo, his quondam commercial art assistant. Such was Warhol’s terror of mortality—especially after he was shot and nearly died, in 1968—that when a Factory “superstar,” Ultra Violet, asked about his beloved mother, Julia Warhola, several years after her death in 1972 he absently replied, “She’s gone to Bloomingdale’s.”