Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) was literature’s great confidence man. Like a Ponzi scheme or a magic trick, his best work is founded on the cornerstone of deceit. In The Inspector-General a young rake inadvertently gulls an entire town into thinking he is an influential government official, then gleefully accepts the bribes and favors that flow his way. In Dead Souls the diabolic anti-hero buys up the names of serfs who have died since the last census in order to pass himself off as a landed gentleman. In the famous short story “The Diary of a Madman,” by contrast, the protagonist seems to play a kind of confidence trick on himself.

Poprishchin, of whose diary entries the story consists, is a low-ranking civil servant, but he remains touchingly unreconciled to his lot in life. A smoking volcano of status anxiety (“why on earth am I a titular councilor? Maybe I’m some sort of count or general and only seem to be a titular councilor”), Poprishchin begins to erupt about halfway through the story when, after reading about the royal succession crisis then occurring in Spain, he believes he has discovered his true identity:

This day—is a day of the greatest solemnity. Spain has a king. He has been found. I am that king. Only this very day did I learn of it…I don’t understand how I could have thought and imagined that I was a titular councilor. How could such a wild notion enter my head?

Before long he is carted off to the nuthouse, which is where we leave him, scribbling away about his metastasizing delusions.

Three distinguished thespians—actor Geoffrey Rush, playwright David Holman, and director Neil Armfield—have bravely adapted Gogol’s tale for the stage but it’s hard not to see the result—now playing at BAM—as a two-hour long category error. You can understand what has long attracted them to “Diary” (Armfield and Rush first adapted it for the stage twenty-two years ago at the Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney): if anyone could play the mentally unspooling part of Poprischin on stage it was going to be Rush. He is an astonishingly gifted and versatile actor who gave the performance of his life as David Helfgott, the gibbering, mole-like, schizoaffective piano virtuoso in Shine, for which he won a much-deserved best actor Oscar in 1996. (He was unlucky not to get one for best supporting actor for his tartly plain-dealing rendition of George VI’s speech therapist in The King’s Speech.) Gogol’s story, with its swarming energies and rampant phantasmagoria (“My head is aflame, and everything spins before my eyes. Save me, someone! Take me away. Give me three steeds, steeds as fast as the whirling wind”), seems not only ripe for dramatic adaptation, but almost Helfgottesque.

Alas, well before the first half of the stage version is over one starts to suspect that Gogol, whose Inspector-General is one of the greatest plays in world literature, made the right choice a hundred and eighty years ago when he decided that “The Diary of a Madman” ought to be a story and not a play. There are several problems in Armfield’s production, but they all stem from what may sound like the relatively technical question of pacing. By distending a brisk tale to two hours (reading it probably takes less than half as long), the BAM Madman gives us time to notice, and be disappointed by, what in the original never seemed like imaginative deficiencies. Whereas the story (to borrow Nabokov’s line on Chekhov) comes in without knocking, the play phones ahead with a very leisurely framing scene (one of the many additions that David Holman’s script makes to Gogol’s original) in which we see Poprischin’s Finnish servant, Tuovi (played by the boisterous Yael Stone), scrubbing the floor of his Petersburg garret.

If Rush’s Helfgott was a miracle of verisimilitude, with his manic speech patterns and unpredictable emotional weather, his Poprishchin feels artificial from the moment he appears on stage, through a staircase in the floor, yelling about the dumplings he is convinced his landlady is withholding from him. Extrapolating from various hints in the story, he moves in clumsy starts and always seems at risk of falling over, as though he has just acquired limbs and is still getting the hang of them. It is Rush’s walk, as much as his fruity, booming voice, that sets the tone for the evening, which will be dominated by a broad, slapstick, crowd-pleasing comedy.

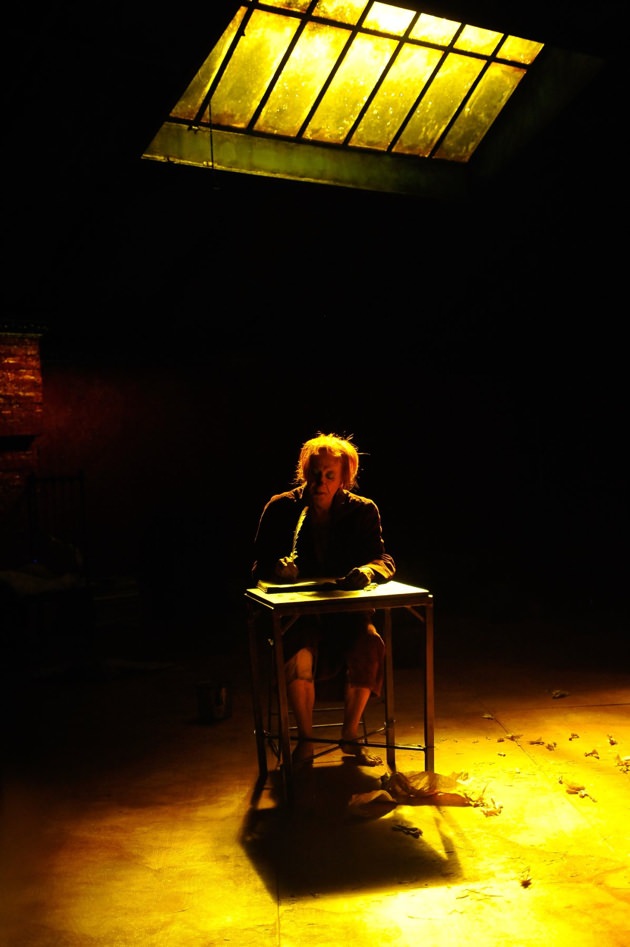

At length he manages to sit down at his desk and start writing about the peculiar things he has been seeing and hearing of late. What quickly becomes clear, as Rush somewhat awkwardly speaks these diary entries aloud, is that there isn’t very much to Poprishchin’s character. One of the reasons Gogol gets away (and, of course, more than gets away) with this is that he does it so quickly. Aside from being a pleasure in itself, the febrile speed with which the story goes by prevents us from noticing that Poprischin is little more than a vivid blur of resentments and anxieties, and the conduit for Gogol’s deracinated poetry. (“Tomorrow at seven o’clock a strange phenomenon will occur: the earth is going to sit on the moon…I confess, I felt troubled at heart when I pictured to myself the extraordinary delicacy and fragility of the moon, etc.”). On stage, and stretched out to two hours, there is no hiding the fact that his solitude (so central to the play) is more or less depthless; there is no introspection, only internal frenzy.

Advertisement

Or as it turns out, external frenzy, for much of Rush’s performance is directed straight at the audience, with whom he quickly establishes an easy rapport. This rapport, however, undermines one of the central qualities of the story, and one of its main sources of pathos: the sense of an ever-dilating solitude and isolation, the sense that we are over-hearing a voice in a vacuum. Rush has a well-stuffed bag of tricks—including the best impression of a cricket I have ever seen by a human being—but his antic virtuosity doesn’t make up for his failure to discover in the role anything resembling emotional depth or complexity. The humor quickly becomes repetitive, because really there is only one joke: that while Poprischin thinks he is privy to all kinds of secret knowledge, he in fact hasn’t a clue what’s going on. As the play wears on, the role starts to feel little more than an opportunity for Rush to showcase his (admittedly vast) talents rather than part of a deliberate and durable whole.

It seems that Rush and his collaborators anticipated these problems and tried to address them by expanding the character of Tuovi, the servant, and Poprishchin’s relationship with her. In this master-servant duo one can discern the outlines of a better, richer play, somewhat in the manner of Beckett’s Endgame, in which Hamm and Clov’s brusque bickering enlivens and diversifies the proceedings (a magnificent production was staged at BAM three years ago).

By the time Poprishchin has been committed, in the second act, Rush is shouting hoarsely and throwing himself wildly about the stage in a desperate attempt to manufacture some pathos. It doesn’t work. We never cared about Poprishchin in the (comparatively sane) first act, and the overwrought histrionics of the second do nothing to change this. The BAM Madman hasn’t been secured by what Henry James called the stout stake of emotion and as a result it simply blows away.

Of course acting—like fiction—is itself a kind of confidence trick; it involves one person trying to persuade an audience he is someone else, or at least to persuade them to suspend their disbelief on this front. During the best performances we almost forget it is a performance we are watching, and something similar happens with the best stories. However hard we try, we’re never allowed to forget this during Rush’s Madman. Unlike Gogol’s tale, where the page at once excludes us from and gives us access to the main character’s experience, at BAM our proximity to Rush prevents us from ever getting close to Poprishchin—or indeed, inside him. Walking out of the theatre I picked up a copy of The Onion, a paper that Gogol, who fused satire and surrealism like no one before or since, would have surely loved. One headline had me laughing especially hard: “Suspension Of Disbelief Goes Unrewarded.”

Diary of a Madman is playing at BAM until March 12.