My father’s friend Maurice, in addition to keeping books for a photography magazine I worked for in the late 1960s, was also in the business of buying and selling paintings. One day he swore me to secrecy and told me that he met a Vanderbilt, a black sheep of the illustrious family. This man, who had spent most of his life being a playboy in Argentina, was now back in New York after forty years and broke. He wanted to sell a Van Dyck and a small Rembrandt from the family collection, and Maurice had arranged for the paintings to be appraised by two reputable galleries, which had certified them as authentic. What made it even more exciting was that Maurice had found a buyer, and the deal was about to be completed. In just a matter of days he was going to be a very rich man.

The buyer’s lawyers required only some additional genealogical information about Mr. Vanderbilt in order to verify how the paintings came into his possession. “Ought to be easy,” Maurice said. He asked me to go to the New York Public Library on 42nd Street, look up the Vanderbilt family tree and take notes. Once he got paid, we’d close the office for a couple of days and do nothing but celebrate. Maurice, who looked like the old French movie actor, Marcel Dalio, was an immigrant from North Africa who came to New York after the Second World War and still spoke with an accent. He told me that he made reservations in three of the best French restaurants in Manhattan, and I knew he wasn’t pulling my leg. Even when he wasn’t peddling masterpieces, he was a generous soul who took his friends out for a good time and always picked up the bill. So I was more than happy to oblige him and do my part in what was to be for him the art sale of a lifetime.

It took me a while to orient myself in the great library, but after consulting a genealogy specialist on the staff, I was given the reliable books and documents on the Vanderbilt family tree. I not only had the name of the fellow I was looking for, but I had also seen him briefly when he stopped by the photography magazine to meet Maurice. He was a tall, lanky, elegant man with bristly gray hair and a face as pale as death. He looked to me like a Nazi war criminal from a grainy, black-and-white 1940s flick. On the other hand, I thought, what the hell do I know about aristocracy? Weren’t old families supposed to be all inbred and a little creepy looking? Be that as it may, I followed the chronology I was given, found some of the ancestors of our Vanderbilt but could not find him.

I went over the charts again and again, even asked the kind librarian who gladly retraced my steps, but I did not immediately grasp the obvious, that the guy I met was not who he pretended to be. I guess my brain had gotten sluggish thinking about all the garlicky escargot, bouillabaisse heaping with fish, the hearty cassoulet with its slow-simmered mix of beans, pork shoulder, sausage, and duck, and the fine old Bordeaux and Burgundies I was going to be enjoying in the matter of days. When it finally hit me that this was some kind of scam, I ran down the wide marble steps of the library in search of a telephone. Unfortunately, the few booths on the ground floor were occupied and there were several people ahead of me cooling their heels. “I have a family emergency,” I shouted, as I pushed them out of the way to grab the next free phone. I told Maurice what I found. I told him once, twice, and then he made me repeat it one more time from the beginning. “I’ll kill the bastard,” he finally shrieked and slammed the phone.

Afterwards, whenever I asked him what had happened, he started cussing and changed the subject, so I never found out the rest of the story. For a few weeks, Maurice seemed to be under the impression that he was still going to collect a part of his fee, but eventually even that hope died. My guess was that the paintings were stolen, the fellow was probably not the thief himself but some crook working for other crooks, and Maurice was the patsy.

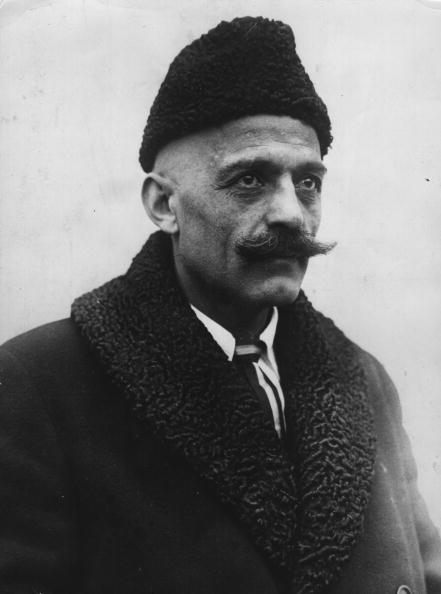

In the meantime, Maurice had another brilliant idea, this one having to do with my father. I was actually there when it popped into his head. The three of us were sitting in one of the German beer halls on 86th Street sipping beer and dipping knockwurst into mustard, when Maurice slapped his forehead. “Doesn’t he look like Gurdjieff to you?” he asked, pointing at my father. I had to agree that there was a strong resemblance to the photograph of the famous spiritual teacher and Eastern mystic, who had dazzled the elites in Paris and New York in 1920s and 1930s.

Advertisement

With his white handlebar moustache, nearly bald head, drooping Levantine eyelids, and air of vast experience and sound judgment, my father always seemed to inspire confidence in others. In the days before credit cards, he could get instant credit in some clothing store on Madison Avenue or a restaurant on the Upper East Side. People trusted him to come back and pay for the suit or the fine meal, and he always did. Still, we had no idea what Maurice had in mind. We soon found out. He thought my father should quit his job at the bank and set up his own esoteric school. “You know all that stuff forwards and backwards, George, so it’ll be easy. We’ll take an ad in The Village Voice; say that you spent years in Tibet, India, and among the Sufis in the Middle East, and that you are now ready to share your vast knowledge with a small number of serious students. Then, we’ll rent a loft downtown, charge twenty dollars per meeting, and watch the money pile up.”

I burst out laughing, but my Pop didn’t think this was funny. He liked a good joke as much as any man I ever met, but here he drew the line. He had been a disciple of Gurdjieff for many years and quoted him all the time, telling me, for instance, that I live my life in a state of hypnotic sleep from which I rarely wake up, and here I was proving his very point by agreeing with Maurice. “Think of all the pretty women lining up to have a private audience with you,” Maurice said. I thought I could detect a momentary interest in my father’s eyes. He already had his own entourage of devotees, as I discovered going to some of the Gurdjieff meetings in New York. To a know-nothing like me, these young women had the alert look and manner of girls who had gone to Vassar or Sarah Lawrence. So, when Maurice told us his idea, I started imagining what it would be like to be the son of the master himself, helping out on the premises, placing cushions on the floor around the chair where he would take his seat, while Maurice stood by the door discreetly asking the prospective disciples for contributions and pocketing the envelopes with money. More importantly, as far as I was concerned, I would be the one these cuties would run to if they felt they were being slighted or misunderstood by the great man.

We ordered more beer and knockwurst and then my father proceeded to tell us what a couple of jerks we were. That didn’t stop Maurice, however. He even went so far as to inquire about the rent for a couple of lofts. What scared me was that the scam probably would have worked. Not for long, of course. My father had enough knowledge of Eastern and Western mysticism to talk for a month without taking a break, but he was not a con man. Still, if he had been persuaded to have one meeting and droves of adoring women had come, I might now be wearing a robe and turban in the Hollywood Hills and not raking leaves in my yard and taking a load of garbage to a small town dump in New Hampshire.