In 2001 I was interviewed by Corriere della Sera about a book I had written on soccer in Italy, and in particular the soccer fans of Hellas Verona. It was a wide-ranging interview on my ten years as a season-ticket holder with the Italian club, the excitements and irritations of travelling regularly with a group of guys who have an exceedingly bad reputation, and in general the anthropology of sports fandom, the mental space it occupies in modern society and so on. When I opened the paper a huge headline read: “HARD-CORE FANS TAUGHT ME HOW TO HATE.”

Needless to say I had said nothing of the kind. What I had talked about was how football rivalries offer people the opportunity to perform a theater of intense emotions that has few or no repercussions on their day-to-day-lives. Since Catholic Italy is a country where the H word is taboo (to the point that relatives of murder victims are immediately asked whether they forgive the assassin, thus showing Christian charity), I wrote a brief letter of protest to Corriere della Sera. Meantime, the journalist who had conducted and written up the interview phoned to apologize and assure me he had had nothing to do with the title. The paper published a few lines of my letter in small print buried deep in its inside sections.

Writer and reader continue to nurture the comforting illusion that they are at opposite ends of a direct line of communication, that the writer has spoken exactly and completely his mind on the matter in question, while the reader has followed and understood his reasoning from beginning to end. In reality, every message, whether in book, newspaper, or blog, is mediated in all kinds of ways, all of which tend to push the text toward two related editorial priorities: melodrama and the received idea. The usual restrictions on length focus the mind and sharpen the pen but severely hinder the writer’s ability to offer a nuanced argument. In-house style policies discourage the writer from developing a different manner of expressing himself; and the way an article is read may also be influenced by the size and nature of the type, the use of photographs and captions, the positioning of the article on the page, the company it keeps there with advertising and other articles, not to mention the way in which paragraphs may be broken up or the article itself split over several pages.

But nothing prejudices the way a reader comes to a piece more than its headline. Nothing is more likely to make him or her believe, even after reading the article through, that the author has said something he has not said and perhaps would never want people to imagine he has said.

I am talking about opinion articles, not news stories. Understandably, editors have a position on major news items and there is a long tradition of giving a sharp alliterative, punning headline to a story that fuses the event itself with the paper’s angle on it. “The Royal Fail,” read a British headline a few days ago on the government’s privatization of the Royal Mail postal service. When papers push this technique to ironic extremes—usually on minor items—the headline becomes more interesting than the piece, a riddle that can only be solved by reading story: “All Kicks off as Hunk makes Flick of Chick being Sick,” is another in today’s Sun. It’s worth reading the British tabloid press if only for the crazy inventiveness of their headlines.

The problem comes when the headline writers bring the same proprietary attitude, the same desire to stimulate their readership’s perceived prejudices, to pieces that are supposed to offer analysis and reflection. This week the veteran left-winger Polly Toynbee, writing in The Guardian, launched a criticism of the present government’s scrapping of a child protection database. The online headline ran “It is the Baby P’s and Hamzah Khans who pay for this Tory vandalism,” referring to two young children who died when the social services failed to save them from repeated domestic violence. However, as it turns out, those children died before the present government came to power and while the database was still in use. Toynbee claimed she was not responsible for the headline.

Because they are not limited by the size of a printed page, online headlines do tend to be longer and, hence give more credibility to the idea that the writer actually expressed the idea they contain. In my own small way I was recently a victim of this: The Independent asked me to write a piece about the decision of the administrators of the Man Booker Prize to open the prize to all novels published in English, hence making American authors eligible. I had five hundred words. I suggested that the Booker decision was part of a long trend towards internationalization of literature that, particularly in countries peripheral to the traditional Western literary intelligentsia, tended to undercut the relationship between an author and his home community, inviting him to write toward a new, international audience. “Historically,” I wrote, “the international award goes hand in hand with the decline of the novel as a serious influence in national debate, or a medium where the native language might be mined and renewed.”

Advertisement

I sent my piece with the headline “Yankee Booker,” which seemed to me punchy enough and clearly indicated. When I saw the piece online (and living as I do in Italy I’m not likely to see the paper version), it came with a double photograph of Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith, as if it were somehow aimed at celebrating or perhaps attacking the phenomenon of literary celebrity. The long headline read: “The rise of the international literary award goes hand in hand with the decline of the novel,” something I hadn’t actually said. Anyone glancing at the page without reading the piece would feel it was a sour-grapes grumble by an author who had been left out of the party, and I suspect even many of those who did go on to read it would still retain this vague impression. Nothing of the sort had been in my mind. Neither Franzen nor Smith was mentioned in the article; what interested me was the continued decline of a certain kind of novel once built on a close relationship between the author and a national readership.

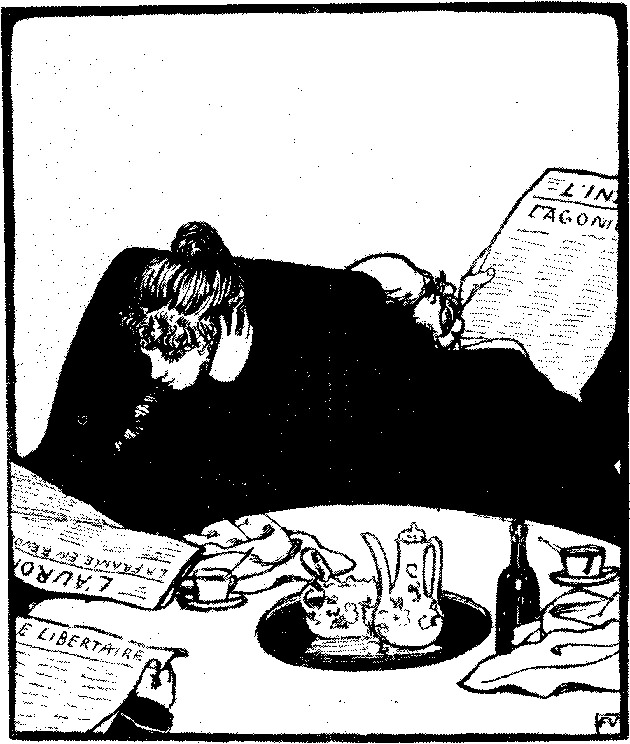

It wasn’t always thus. Up until about a century ago, a headline or title was usually a neutral attempt to inform the reader of the contents of an article or book. But as the twentieth century progressed, or regressed, it was more and more understood as an advertising opportunity and the writing itself as no more, no less, than “content”—a consumer good. Newspapers on the verge of financial meltdown grow desperate and clearly seek to gratify their particular readership’s supposed prejudices. I just heard a BBC interview with Alan Rusbridger, the editor of the leftwing Guardian, about an ongoing spat between his paper and the rightwing Daily Mail. Rusbridger spoke of a mutual respect between two papers that knew how to give their target readership what they wanted. He didn’t appear to realize how depressing and patronizing this was as a comment on both readers and journalists. As if the argument between the papers was in fact no more than an effective commercial ploy.

Dishonesty of headlining may seem a minor issue. It isn’t. It’s a sign of a wider malaise. The health of democracy is the health of the collective mind, but one increasingly comes away from a newspaper or a computer screen with the sense of having been exposed to a hail of darts, all aimed at inflaming and exciting the mind, but rarely instructing. And of course we all read far more headlines than we do articles, far more Tweets, captions, slogans, and pop ups, in a process which is part of the general division of attention in the electronic devices vibrating in our pockets, the websites we keep in background, the messages constantly coming to us from posters, screens and PA systems. The tendency is always toward provoking us to react, in a complacent and unreflecting way: I read this and feel angry, I read that and feel vindicated, I read the other and feel anxious, over-anxious.

Even the NYRblog has occasionally come up with headlines I felt were more provocative than helpful. A piece on how my novel Cleaver was entirely transformed in the German film version Cliewer was originally titled, “How the Germans Annexed My Novel.” This sounded like war-talk to me. But unlike newspapers, the blog is sensitive to feedback and the title was quickly changed to “My Novel, Their Culture”—at once more effective and less potentially offensive. In general, as a recent blog reviewing headlines in fifty years of The New York Review of Books observes, it’s reassuring how frequently the editors have settled for simple solutions such as “The Case of So & So,” “The Mysteries of This or That,” “The Man Who Did This,” or “The Woman Who Did That,” or just straightforward questions, “How Smart are Computers?” “Who was Mao Zedung?” In the end to invite a quietly reflective state of mind may actually be a more important task for a newspaper, certainly a more useful contribution, than to draw the public to a particular political or cultural position, or worse still to reinforce and gratify the position editors assume they already have.

Advertisement

I could finish here, but in the hope that someone may have the time and interest, here is an extract, dated October 1821, from the notebook of Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi, that may throw some light on the matter:

The power of nature and the weakness of reason. I’ve said elsewhere that for opinions to have a real influence on people they must take the form of passions. So long as man has anything natural about him, he will be more passionate about opinion than about his passions. One could quote endless examples to demonstrate this point. But since all opinions that aren’t, or don’t seem to be prejudices, will have only pure reason to support them, in the ordinary way of things they are completely powerless to influence people. Religious folks (even today, and maybe more these days than ever before, *in reaction to the opposition they meet*) are more passionate about their religion than their other passions (to which religion is hostile); they sincerely hate people who are not religious (though they pretend not to) and would make any sacrifice to see their system triumph (actually they already do this, mortifying inclinations that are natural and contrary to religion), and they feel intense anger whenever religion is humbled or contested. Non-religious people, on the other hand, so long as their not being religious is simply the result of a cool-headed conviction, or of doubt, don’t hate religious people and wouldn’t make sacrifices for their unbelief, etc., etc. So it is that hatred over matters of opinion is never reciprocal, except in those cases where for both sides the opinion is a prejudice, or takes that form. There’s no war then between prejudice and reason, but only between prejudice and prejudice, or rather, only prejudice has the will to fight, not reason. The wars, hostilities and hatreds over opinions, so frequent in ancient times, right up to the present day in fact, wars both public and private, between parties, sects, schools, orders, nations, individuals—wars which naturally made people determined enemies of anyone who held an opinion different from their own—only happened because pure reason never found any place in their opinions, they were all just prejudices, or took that form, and hence were really passions. Poor philosophy then, that people talk so much about and place so much trust in these days. She can be sure no-one will fight for her, though her enemies will fight her with ever greater determination; and the less philosophy influences the world and reality, the greater her progress will be, I mean the more she purifies herself and distances herself from prejudice and passion. So never hope anything from philosophy or the reasonableness of this century.